No related resources

Introduction

The government brought forth by the Articles of Confederation worked just as designed. Unfortunately, it was not really designed to work as a government. Everything remained voluntary. Congress provided a forum for discussion and debate, but it had no power to tax (unless one counts draining paper money of its value through the act of printing more of it) and it had no power to compel the thirteen states to provide it with funds or comply with its decisions. These restrictions made sense given Americans’ experience with British imperial rule, but sometimes government power possesses a greater potential to secure liberty than to threaten it. Drafted in 1777 and finally ratified in 1781, the Articles reflected the Spirit of ‘76 more than the requirements of a costly eight-year War for Independence.

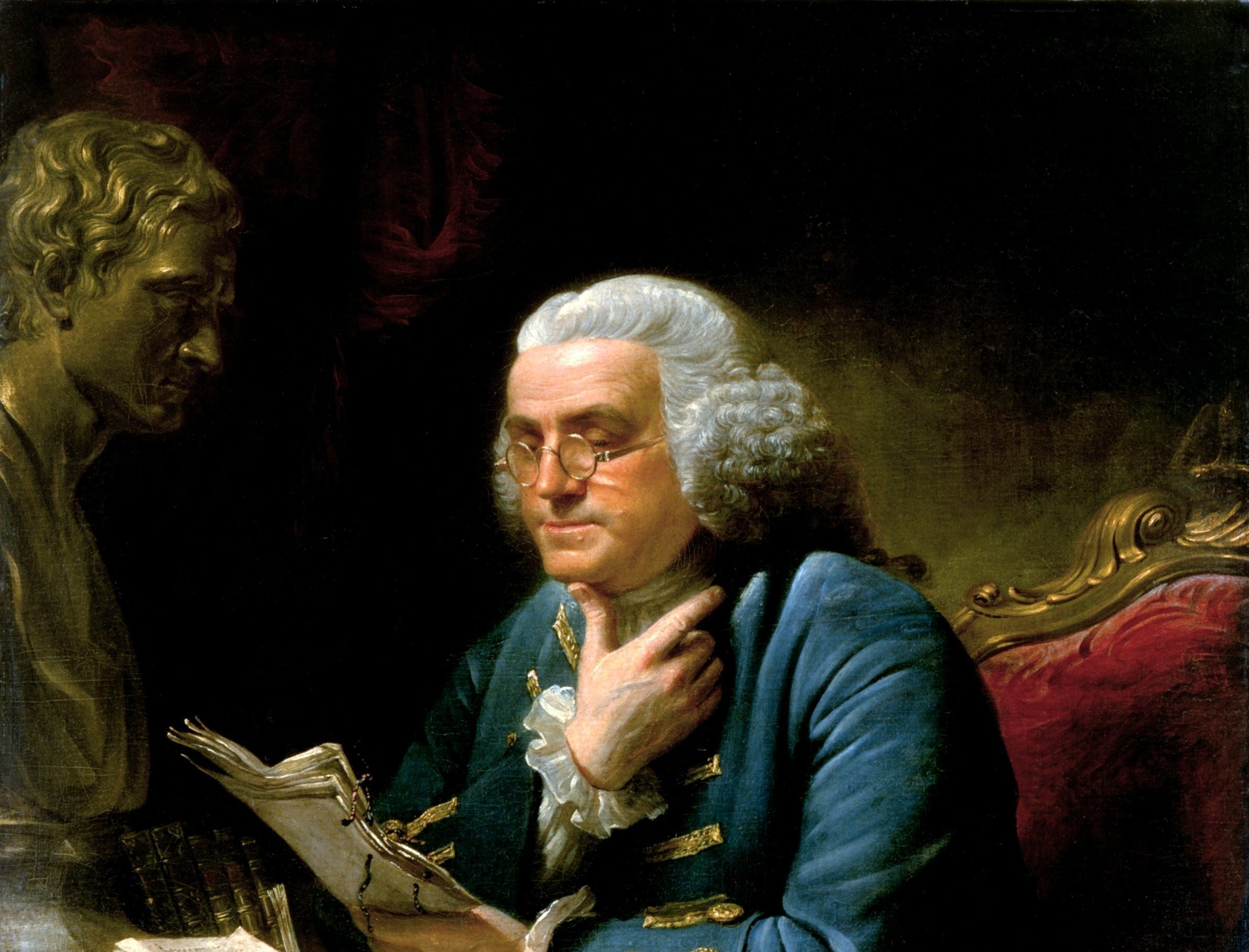

No one better understood the inadequacies of the Articles than General George Washington (1732–1799), whose army had suffered almost continuously from a lack of pay and provisions. As Washington knew too well, the inability of a near-bankrupt Congress to compensate his officers—in the past, present, and, as many worried, in the future—led to the near mutinous Newburgh conspiracy. In March 1783 he had defused that powder keg, in part, by promising to continue his efforts to secure justice for the officers and soldiers of the Continental army.

Here, in a “circular letter” addressed to the governor of each state, Washington made good on that promise. Making the most of America’s victory in the War for Independence as an occasion not only for celebration but also as an opportunity to warn of possible future difficulties, Washington made clear his desire for a more muscular alternative to the status quo of the Articles of Confederation.

Source: George Washington to the States, June 8–21, 1783, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11404.

The great object, for which I had the honor to hold an appointment in the service of my country being accomplished, I am now preparing to resign it into the hands of Congress, and to return to that domestic retirement; which it is well known I left with the greatest reluctance, a retirement for which I have never ceased to sigh through a long and painful absence, and in which (remote from the noise and trouble of the world) I meditate to pass the remainder of life, in a state of undisturbed repose. But before I carry this resolution into effect, I think is a duty incumbent on me, to make this my last official communication; to congratulate you on the glorious events which Heaven has been pleased to produce in our favor; to offer my sentiments respecting some important subjects which appear to me to be intimately connected with the tranquility of the United States; to take my leave of your excellency as a public character; and to give my final blessing to that country, in whose service I have spent the prime of my life, for whose sake I have consumed so many anxious days and watchful nights, and whose happiness, being extremely dear to me, will always constitute no inconsiderable part of my own….

The citizens of America, placed in the most enviable condition, as the sole lords and proprietors of a vast tract of continent, comprehending all the various soils and climates of the world and abounding with all the necessaries and conveniences of life, are now, by the late satisfactory pacification, acknowledged to be possessed of absolute freedom and independency. They are from this period to be considered as the actors, on a most conspicuous theater, which seems to be peculiarly designated by Providence for the display of human greatness and felicity. Here they are not only surrounded with everything which can contribute to the completion of private and domestic enjoyment, but Heaven has crowned all its other blessings by giving a fairer opportunity for political happiness, than any other nation has ever been favored with. Nothing can illustrate these observations more forcibly than a recollection of the happy conjuncture of times and circumstances under which our republic assumed its rank among the nations. The foundation of our empire was not laid in the gloomy age of ignorance and superstition, but at an epoch when the rights of mankind were better understood and more clearly defined, than at any former period….

Such is our situation, and such are our prospects; but notwithstanding the cup of blessing is thus reached out to us; notwithstanding happiness is ours if we have a disposition to seize the occasion and make it our own. Yet it appears to me there is an option still left to the United States of America; that it is in their choice and depends upon their conduct, whether they will be respectable and prosperous or contemptible and miserable as a nation. This is the time of their political probation; this is the moment when the eyes of the whole world are turned upon them. This is the moment to establish or ruin their national character forever. This is the favorable moment to give such a tone to our federal government, as will enable it to answer the ends of its institution—or this may be the ill-fated moment for relaxing the powers of the Union, annihilating the cement of the Confederation, and exposing us to become the sport of European politics, which may play one state against another, to prevent their growing importance, and to serve their own interested purposes. For, according to the system of policy the states shall adopt at this moment, they will stand or fall, and by their confirmation or lapse, it is yet to be decided whether the Revolution must ultimately be considered as a blessing or a curse; a blessing or a curse, not to the present age alone, for with our fate will the destiny of unborn millions be involved.

With this conviction of the importance of the present crisis, silence in me would be a crime. I will therefore speak to your excellency the language of freedom and sincerity without disguise. I am aware, however, that those who differ from me in political sentiment may perhaps remark I am stepping out of the proper line of my duty, and they may possibly ascribe to arrogance or ostentation what I know is alone the result of the purest intention. But the rectitude of my own heart, which disdains such unworthy motives; the part I have hitherto acted in life; the determination I have formed of not taking any share in public business hereafter; the ardent desire I feel and shall continue to manifest of quietly enjoying, in private life, after all the toils of war, the benefits of a wise and liberal government, will, I flatter myself, sooner or later convince my countrymen that I could have no sinister views in delivering, with so little reserve, the opinions contained in this address.

There are four things, which I humbly conceive are essential to the well-being, I may venture to say, to the existence, of the United States as an independent power:

First. An indissoluble union of the states under one federal head.

Secondly. A sacred regard to public justice.

Thirdly. The adoption of a proper peace establishment—and

Fourthly. The prevalence of that pacific and friendly disposition among the people of the United States, which will induce them to forget their local prejudices and policies; to make those mutual concessions which are requisite to the general prosperity; and, in some instances, to sacrifice their individual advantages to the interest of the community.

These are the pillars on which the glorious fabric of our independency and national character must be supported. Liberty is the basis—and whoever would dare to sap the foundation, or overturn the structure, under whatever specious pretexts he may attempt it, will merit the bitterest execration and the severest punishments which can be inflicted by his injured country.

On the three first articles I will make a few observations, leaving the last to the good sense and serious consideration of those immediately concerned.

Under the first head, although it may not be necessary or proper for me… to enter into a particular disquisition of the principles of the Union and to take up the great question which has been frequently agitated, whether it be expedient and requisite for the states to delegate a larger proportion of power to Congress, or not; yet it will be a part of my duty, and that of every true patriot, to assert without reserve and to insist upon the following positions. That, unless the states will suffer Congress to exercise those prerogatives they are undoubtedly invested with by the constitution, everything must very rapidly tend to anarchy and confusion. That it is indispensible to the happiness of the individual states that there should be lodged somewhere a supreme power to regulate and govern the general concerns of the confederated republic, without which the Union cannot be of long duration. That there must be a faithful and pointed compliance, on the part of every state, with the late proposals and demands of Congress, or the most fatal consequences will ensue; that whatever measures have a tendency to dissolve the Union, or contribute to violate or lessen the sovereign authority, ought to be considered as hostile to the liberty and independency of America, and the authors of them treated accordingly. And last, that unless we can be enabled, by the concurrence of the states, to participate of the fruits of the Revolution, and enjoy the essential benefits of civil society, under a form of government so free and uncorrupted, so happily guarded against the danger of oppression, as has been devised and adopted by the Articles of Confederation, it will be a subject of regret that so much blood and treasure have been lavished for no purpose, that so many sufferings have been encountered without a compensation, and that so many sacrifices have been made in vain.

Many other considerations might here be adduced to prove, that, without an entire conformity to the spirit of the Union, we cannot exist as an independent power. It will be sufficient for my purpose, to mention but one or two, which seem to me of the greatest importance. It is only in our united character, as an empire, that our independence is acknowledged, that our power can be regarded, or our credit supported among foreign nations. The treaties of the European powers with the United States of America will have no validity on a dissolution of the Union. We shall be left nearly in a state of nature; or we may find, by our own unhappy experience, that there is a natural and necessary progression from the extreme of anarchy to the extreme of tyranny, and that arbitrary power is most easily established on the ruins of liberty abused to licentiousness.

As to the second article, which respects the performance of public justice, Congress have, in their late address to the United States, almost exhausted the subject; they have explained their ideas so fully, and have enforced the obligations the states are under, to render complete justice to all the public creditors, with so much dignity and energy, that, in my opinion, no real friend to the honor and independency of America can hesitate a single moment respecting the propriety of complying with the just and honorable measures proposed. If their arguments do not produce conviction, I know of nothing that will have greater influence, especially when we recollect that the system referred to, being the result of the collected wisdom of the continent, must be esteemed, if not perfect, certainly the least objectionable of any that could be devised; and that, if it shall not be carried into immediate execution, a national bankruptcy, with all its deplorable consequences, will take place before any different plan can possibly be proposed and adopted, so pressing are the present circumstances! And such is the alternative now offered to the states!

The ability of the country to discharge the debts, which have been incurred in its defense, is not to be doubted; an inclination, I flatter myself, will not be wanting. The path of our duty is plain before us. Honesty will be found on every experiment to be the best and only true policy. Let us then, as a nation, be just—let us fulfill the public contracts which Congress had undoubtedly a right to make for the purpose of carrying on the war, with the same good faith we suppose ourselves bound to perform our private engagements. In the meantime let an attention to the cheerful performance of their proper business as individuals and as members of society be earnestly inculcated on the citizens of America. Then will they strengthen the hands of government and be happy under its protection; everyone will reap the fruit of his labors, everyone will enjoy his own acquisitions without molestation and without danger.

In this state of absolute freedom and perfect security, who will grudge to yield a very little of his property to support the common interests of society and ensure the protection of government? Who does not remember the frequent declarations at the commencement of the war that we should be completely satisfied, if at the expense of one half, we could defend the remainder of our possessions? Where is the man to be found, who wishes to remain indebted for the defense of his own person and property, to the exertions, the bravery, and the blood of others, without making one generous effort to repay the debt of honor and of gratitude? In what part of the continent shall we find any man, or body of men, who would not blush to stand up and propose measures purposely calculated to rob the soldier of his stipend and the public creditor of his due? And were it possible that such a flagrant instance of injustice could ever happen, would it not excite the general indignation and tend to bring down upon the authors of such measures the aggravated vengeance of Heaven?…

For my own part, conscious of having acted, while a servant of the public, in the manner I conceived best suited to promote the real interests of my country; having, in consequence of my fixed belief, in some measure, pledged myself to the army that their country would finally do them complete and ample justice; and not wishing to conceal any instance of my official conduct from the eyes of the world, I have thought proper to transmit to your excellency the enclosed collection of papers relative to the half-pay and commutation granted by Congress to the officers of the army. From these communications, my decided sentiment will be clearly comprehended, together with the conclusive reasons which induced me, at an early period, to recommend the adoption of this measure, in the most earnest and serious manner. As the proceedings of Congress, the army, and myself are open to all, and contain, in my opinion, sufficient information to remove the prejudices and errors, which may have been entertained by any, I think it unnecessary to say anything more, than just to observe, that the resolutions of Congress now alluded to, are undoubtedly as absolutely binding upon the United States, as the most solemn acts of confederation or legislation….

It is necessary to say but a few words on the third topic which was proposed and which regards particularly the defense of the republic—as there can be little doubt but Congress will recommend a proper peace establishment for the United States, in which a due attention will be paid to the importance of placing the militia of the Union upon a regular and respectable footing. If this should be the case, I would beg leave to urge the great advantage of it in the strongest terms. The militia of this country must be considered as the Palladium[1] of our security and the first effectual resort in case of hostility. It is essential, therefore, that the same system should pervade the whole—that the formation and discipline of the militia of the continent should be absolutely uniform and the same species of arms, accouterments, and military apparatus should be introduced in every part of the United States. No one, who has not learned it from experience, can conceive the difficulty, expense, and confusion, which result from a contrary system, or the vague arrangements which have hitherto prevailed.

If, in treating of political points, a greater latitude than usual has been taken in the course of this address, the importance of the crisis, and the magnitude of the objects in discussion, must be my apology. It is, however, neither my wish nor expectation, that the preceding observations should claim any regard, except so far as they shall appear to be dictated by a good intention, consonant to the immutable rules of justice, calculated to produce a liberal system of Policy and founded on what ever experience may have been acquired by a long and close attention to public business. Here I might speak with the more confidence, from my actual observations, and, if it would not swell this letter (already too prolix)[2] beyond the bounds I had prescribed myself, I could demonstrate to every mind open to conviction, that in less time and with much less expense than has been incurred, the war might have been brought to the same happy conclusion if the resources of the continent could have been properly drawn forth—that the distresses and disappointments, which have very often occurred, have in too many instances resulted more from a want of energy in the Continental government, than a deficiency of means in the particular states. That the inefficacy of measures, arising from the want of an adequate authority in the supreme power, from a partial compliance with the requisitions of Congress in some of the states and from a failure of punctuality in others, while it tended to damp the zeal of those which were more willing to exert themselves, served also to accumulate the expenses of the war and to frustrate the best concerted plans; and that the discouragement, occasioned by the complicated difficulties and embarrassments in which our affairs were by this means involved, would have long ago produced the dissolution of any army, less patient, less virtuous, and less persevering than that which I have had the honor to command….

I have thus freely disclosed, what I wished to make known, before I surrendered up my public trust to those who committed it to me. The task is now accomplished. I now bid adieu[3] to your excellency, as the chief magistrate of your state, at the same time I bid a last farewell to the cares of office and all the employments of public life.

It remains then to be my final and only request, that your excellency will communicate these sentiments to your legislature at their next meeting and that they may be considered as the legacy of one who has ardently wished on all occasions to be useful to his country and who, even in the shade of retirement, will not fail to implore the divine benediction upon it.

I now make it my earnest prayer, that God would have you and the state over which you preside, in his holy protection; that he would incline the hearts of the citizens to cultivate a spirit of subordination and obedience to government; to entertain a brotherly affection and love for one another, for their fellow citizens of the United States at large, and particularly for their brethren who have served in the field; and finally, that he would most graciously be pleased to dispose us all to do justice, to love mercy, and to demean ourselves, with that charity, humility, and pacific temper of mind, which were the characteristics of the Divine Author of our blessed religion, and without a humble imitation of whose example in these things, we can never hope to be a happy nation….

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.