Introduction

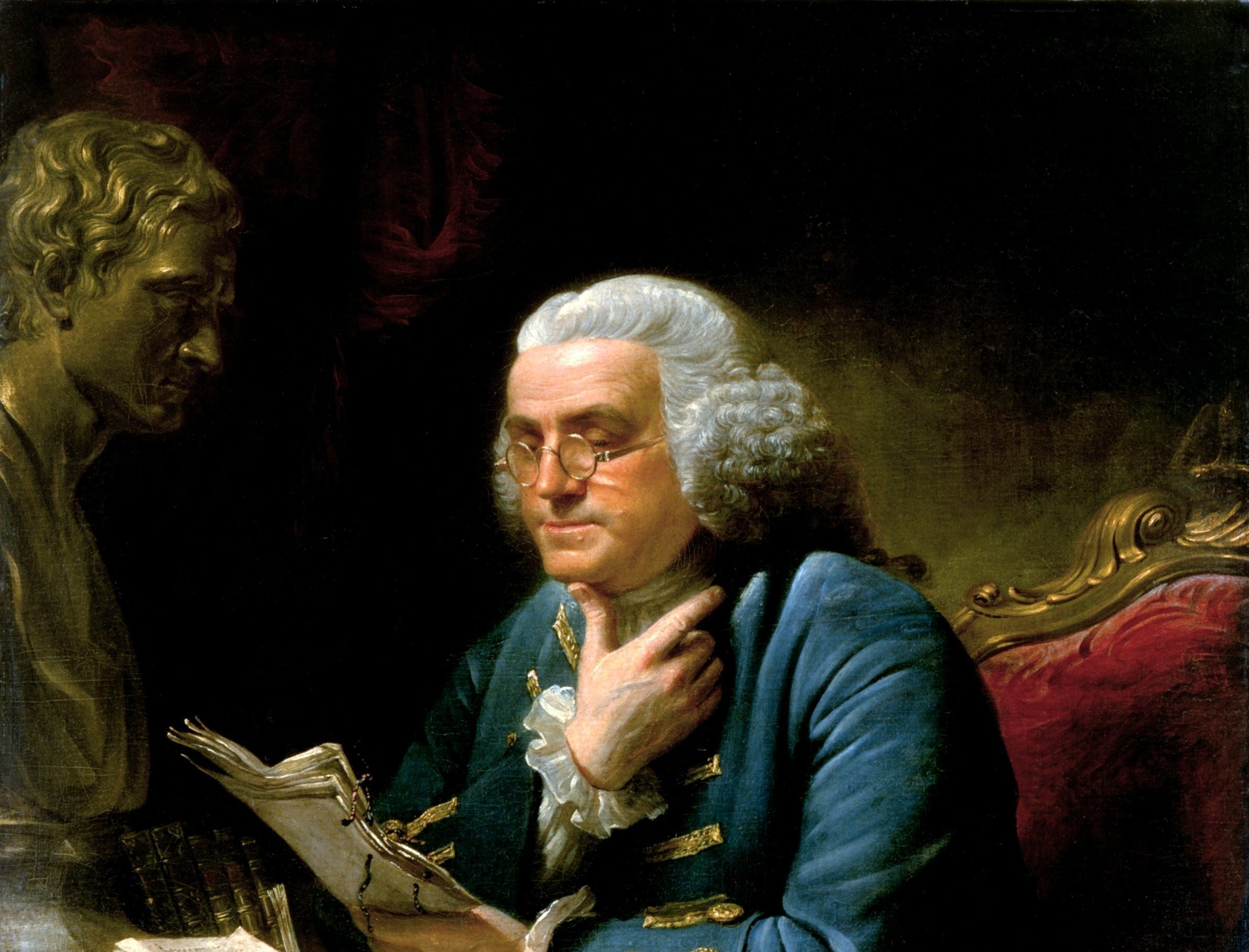

Acting on instructions from the Virginia Convention, on June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee (1732–1794) stood before his fellow members of the Continental Congress to propose a resolution “that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states.” After John Adams (1735–1826) of Massachusetts seconded the motion, debate raged for two full days. Finally, Congress decided to table Lee’s resolution for three weeks in order to allow delegates to receive instructions from their legislatures. In the meantime, in the event that the resolution should pass, it appointed a committee to draft a declaration of independence. The committee consisted of Adams, Roger Sherman (1721–1793) of Connecticut, Robert R. Livingston (1746–1814) of New York, Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) of Pennsylvania, and Virginia delegate Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826).

Jefferson thought that Adams should take the lead in composing a draft, but Adams disagreed. As he later recalled, he insisted that Jefferson accept the task for three reasons: “Reason first, you are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second, I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. You are very much otherwise. Reason third, you can write ten times better than I can.” Adams appreciated not only Jefferson’s “happy talent for composition” but also his status as the committee’s only southerner. New England delegates stood firmly behind independence. Adams himself had pushed the idea so insistently that he sensed the annoyance of certain delegates, who believed that Massachusetts, which had borne the brunt of British sanctions and gunfire, stood to gain the most from separation from Great Britain. If a popular delegate from Virginia championed independence, then maybe wavering delegates from the middle colonies and South Carolina would too.

Accepting the task, Jefferson got to work in his rented rooms at the house of Jacob Graff (1727–1780), a Philadelphia bricklayer. For nearly three weeks Jefferson worked through a succession of drafts. He wrote, revised, and sought feedback from Adams, Franklin, and finally the entire committee.

The Declaration, he later wrote, aimed “to be an expression of the American mind.” It sought “not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of … but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent.” Not everyone assented, however. John Dickinson (1732–1808), a member of Congress who had labored mightily in opposition to British imperial policies (Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, No. II and Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms), could not bring himself to vote for independence. Considering it too much, too soon, and too sure to further inflame a war already raging out of control, he marveled at his peers’ willingness to “brave the storm in a skiff made of paper.”

On July 2, once Congress voted in favor of Lee’s resolution, it turned its attention to Jefferson’s draft. In Jefferson’s notes on the debate over the Declaration, he provided a brief account of how his draft was amended; he then transcribed the draft he had submitted to Congress to show how it had been changed. The text below includes Jefferson’s explanatory note and underlines, as Jefferson did, the parts of the Declaration deleted by Congress. In Jefferson’s original transcription, the words and phrases inserted by Congress are displayed in the margin; here they are italicized and placed within curly brackets in the body of the text.

Source: H. A. Washington, ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, 9 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Taylor and Maury, 1853–54), 1:19–26. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000365325

… Congress proceeded the same day [July 2] to consider the Declaration of Independence, which had been reported and laid on the table the Friday preceding, and on Monday referred to a committee of the whole. The pusillanimous idea that we had friends in England worth keeping terms with, still haunted the minds of many. For this reason, those passages which conveyed censures on the people of England were struck out, lest they should give them offense. The clause too, reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa, was struck out in complaisance[1] to South Carolina and Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves, and who, on the contrary, still wished to continue it. Our northern brethren also, I believe, felt a little tender under those censures; for though their people have very few slaves themselves, yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others. The debates, having taken up the greater parts of the 2rd, 3rd, and 4th days of July, were, in the evening of the last, closed; the Declaration was reported by the committee, agreed to by the House, and signed by every member present,[2] except Mr. Dickinson.[3] As the sentiments of men are known not only by what they receive, but what they reject also, I will state the form of the Declaration as originally reported. The parts struck out by Congress shall be distinguished by a black line drawn under them; and those inserted by them shall be placed in the margin or in a concurrent column(s).

A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with {certain} inherent and inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, begun at a distinguished period and pursuing invariably the same object, evinces[4] a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of these colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to {alter} expunge their former systems of government. The history of the present king of Great Britain is a history of {repeated} unremitting injuries and usurpations, among which appears no solitary fact to contradict the uniform tenor of the rest but all have {all having} in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over these states. To prove this let facts be submitted to a candid world for the truth of which we pledge a faith yet unsullied by falsehood.

He has refused his assent to laws the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his governors to pass laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his assent should be obtained; and, when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of representation in the legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to the tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved representative houses repeatedly and continually for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time after such dissolutions to cause others to be elected, whereby the legislative powers, incapable of annihilation, have returned to the people at large for their exercise, the state remaining, in the meantime, exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without and convulsions within.

He has endeavored to prevent the population of these states; for that purpose obstructing the laws for naturalization of foreigners, refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new appropriations of lands.

He has {obstructed} suffered the administration of justice totally to cease in some of these states {by} refusing his assent to laws for establishing judiciary powers.

He has made our judges dependent on his will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of new offices by a self assumed power and sent hither swarms of new officers to harass our people and eat our their substance.

He has kept among us in times of peace standing armies and ships of war without the consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the military independent of, and superior to, the civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitutions and unacknowledged by our laws, giving his assent to their acts of pretended legislation for quartering large bodies of armed troops among us; for protecting them by a mock trial from punishment for any murders which they should commit on the inhabitants of these states; for cutting off our trade with all parts of the world; for imposing taxes on us without our consent; for depriving us {in many cases} of the benefits of trial by jury; for transporting us beyond seas to be tried for pretended offences; for abolishing the free system of English laws in a neighboring province,[5] establishing therein an arbitrary government, and enlarging its boundaries, so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these {colonies} states; for taking away our charters, abolishing our most valuable laws, and altering fundamentally the forms of our governments; for suspending our own legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated government here {by declaring us out of his protection and waging war against us.} withdrawing his governors, and declaring us out of his allegiance and protection.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large armies of foreign mercenaries to complete the works of death, desolation and tyranny already begun with circumstances of cruelty and perfidy[6] {scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally} unworthy the head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow citizens taken captive on the high seas, to bear arms against their country, to become the executioners of their friends and brethren, or to fall themselves by their hands.

He has {excited domestic insurrections among us, and has} endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions of existence.

He has incited treasonable insurrections of our fellow citizens, with the allurements of forfeiture and confiscation of our property.

He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of INFIDEL powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought and sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce. And that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die,[7] he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people on whom he also obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed against the LIBERTIES of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the LIVES of another.

In every stage of these oppressions we have petitioned for redress in the most humble terms: our repeated petitions have been answered only by repeated injuries.

A prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a tyrant is unfit to be the ruler of a {free} people who mean to be free. Future ages will scarcely believe that the hardiness of one man adventured, within the short compass of twelve years only, to lay a foundation so broad and so undisguised for tyranny over a people fostered and fixed in principle of freedom.

Nor have we been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend {an unwarrantable} a jurisdiction over {us} these our states. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here, no one of which could warrant so strange a pretension: that these were effected at the expense of our own blood and treasure, unassisted by the wealth or the strength of Great Britain: that in constituting indeed our several forms of government, we had adopted one common king, thereby laying a foundation for perpetual league and amity with them: but that submission to their parliament was no part of our constitution, nor ever in idea, if history may be credited: and, we {have} appealed to their native justice and magnanimity and {we have conjured them by} as well as to the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations which {would inevitably} were likely to interrupt our connection and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity, and when occasions have been given them, by the regular course of their laws, of removing from their councils the disturbers of our harmony, they have, by their free election, re-established them in power. At this very time too, they are permitting their chief magistrate to send over not only soldiers of our common blood, but Scotch and foreign mercenaries to invade and destroy us. These facts have given the last stab to agonizing affection, and manly spirit bids us to renounce forever these unfeeling brethren. We must endeavor to forget our former love for them, and to hold them as we hold the rest of mankind, enemies in war, in peace friends. We might have been a free and a great people together; but a communication of grandeur and of freedom, it seems, is below their dignity. Be it so, since they will have it. The road to happiness and to glory is open to us too. We will tread it apart from them, and {We must therefore} acquiesce in the necessity which denounces our eternal separation {and hold them as we hold the rest of mankind, enemies in war, in peace friends.}!

Editor: The two final paragraphs, in their original and amended forms, were placed by Jefferson in two parallel columns. The conclusion of the Declaration as he submitted it appeared in the left column and the text as altered by Congress appeared in the right column.

[Jefferson’s draft]

We, therefore, the representatives of the United States of America in General Congress assembled, do in the name, and by the authority of the good people of these states reject and renounce all allegiance and subjection to the kings of Great Britain and all others who may hereafter claim by, through or under them; we utterly dissolve all political connection which may heretofore have subsisted between us and the people or parliament of Great Britain: and finally we do assert and declare these colonies to be free and independent states, and that as free and independent states, they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do.

And for the support of this declaration, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.

[Congress’s final version]

We, therefore, the representatives of the United States of America in General Congress assembled, appealing to the supreme judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do in the name, and by the authority of the good people of these colonies, solemnly publish and declare, that these united colonies are, and of right ought to be free and independent states; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved; and that as free and independent states, they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce and to do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do.

And for the support of this declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.

- 1. In order to comply with the wishes of.

- 2. Jefferson’s memory deceived him. Although the Continental Congress approved the text of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, the official parchment copy was not signed by delegates until August 1776.

- 3. John Dickinson (1732–1808), one of Pennsylvania’s delegates to the Continental Congress, withheld his signature because he still hoped for reconciliation with Great Britain.

- 4. Reveals, demonstrates, makes evident.

- 5. Canada.

- 6. Treachery, deceitfulness, untrustworthiness.

- 7. A stamp used to certify government documents.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.