No related resources

Introduction

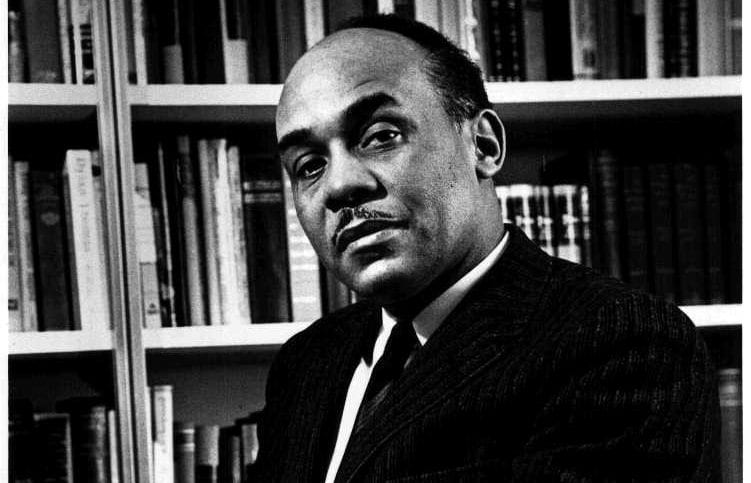

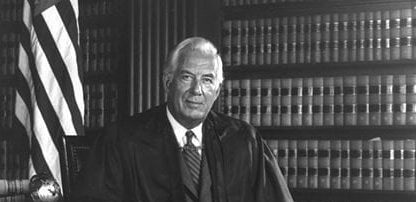

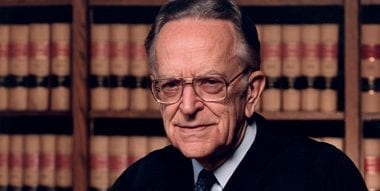

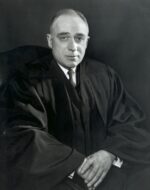

The school prayer case of Engel v. Vitale pitted the Court against the long-standing American tradition of praying in public school. Expanding the principle he set forth in Everson v. Board of Education and following incorporation of the First Amendment into the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, Justice Hugo L. Black contended that a school prayer was a state-sponsored prayer and thus established a state religion. For this reason, he did not need to address the issues in West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette about compulsory or even voluntary prayer or, more broadly, speech or expression that might violate one’s conscience.

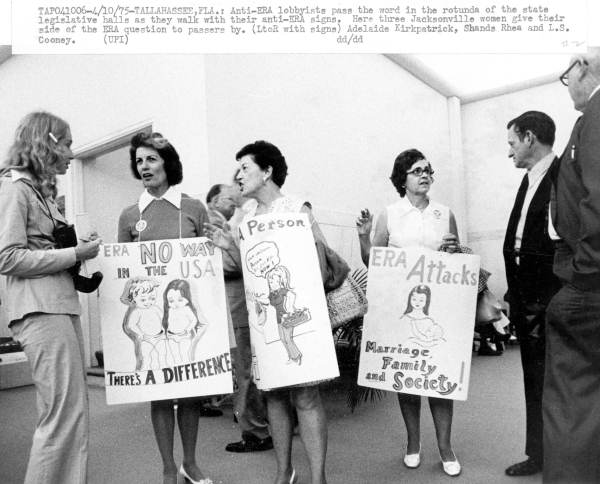

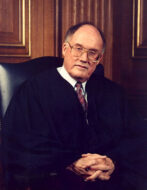

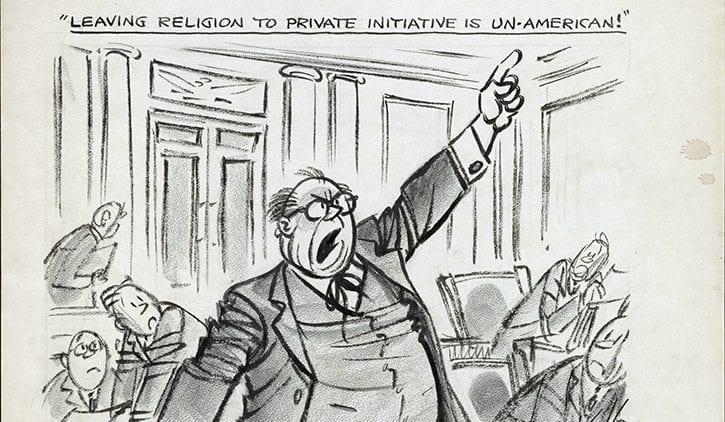

Not surprisingly, the Court’s opinion met with fierce opposition, which included calls for a constitutional amendment reversing the decision, a denunciation of secularism, and rejection of federal aid to education. For a comprehensive dissent to this and other early Establishment Clause cases, see Justice William H. Rehnquist in Wallace v. Jaffree, which voided an Alabama statute requiring moments of silence in public schools. Justice David H. Souter criticized this dissent in various opinions, including his concurrence in the public school commencement prayer case Lee v. Weisman. The Court eventually expanded its Establishment Clause argument to cover prayers at high school pep assemblies before football games (Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, 2000).

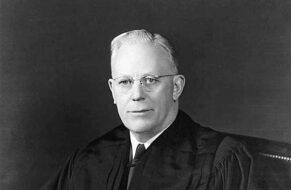

The facts of the case are presented in Justice Black’s Court opinion. The Court decided the case 6–1, Justice Potter Stewart dissenting. Justices Felix Frankfurter and Byron R. White did not participate in the decision.

Source: 370 U.S. 421, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/370/421. We include excerpts of Justice Black’s opinion for the Court. We omit Justice William O. Douglas’s concurring opinion and Justice Stewart’s dissent. Footnotes added by the editors are preceded by “Ed. note.”

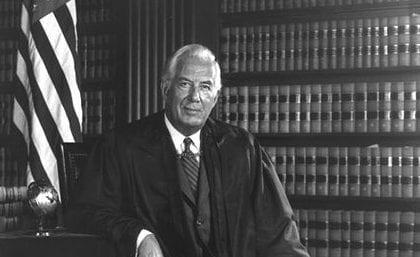

MR. JUSTICE BLACK delivered the opinion of the Court.

The respondent[1] Board of Education of Union Free School District No. 9, New Hyde Park, New York, acting in its official capacity under state law, directed the school district’s principal to cause the following prayer to be said aloud by each class in the presence of a teacher at the beginning of each school day: “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our country.” This daily procedure was adopted on the recommendation of the State Board of Regents, a governmental agency created by the state Constitution to which the New York Legislature has granted broad supervisory, executive, and legislative powers over the state’s public school system. These state officials composed the prayer which they recommended and published as a part of their “Statement on Moral and Spiritual Training in the Schools,” saying: “We believe that this statement will be subscribed to by all men and women of good will, and we call upon all of them to aid in giving life to our program.” Shortly after the practice of reciting the regents’ prayer was adopted by the school district, the parents of ten pupils brought this action in a New York State Court insisting that use of this official prayer in the public schools was contrary to the beliefs, religions, or religious practices of both themselves and their children. . . . The New York Court of Appeals . . . sustained an order of the lower state courts which had upheld the power of New York to use the regents’ prayer as a part of the daily procedures of its public schools so long as the schools did not compel any pupil to join in the prayer over his or his parents’ objection. We granted certiorari[2] to review this important decision involving rights protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

We think that, by using its public school system to encourage recitation of the regents’ prayer, the State of New York has adopted a practice wholly inconsistent with the Establishment Clause. There can, of course, be no doubt that New York’s program of daily classroom invocation of God’s blessings as prescribed in the regents’ prayer is a religious activity. It is a solemn avowal of divine faith and supplication for the blessings of the Almighty. The nature of such a prayer has always been religious, none of the respondents has denied this, and the trial court expressly so found. . . .

It is a matter of history that this very practice of establishing governmentally composed prayers for religious services was one of the reasons which caused many of our early colonists to leave England and seek religious freedom in America. The Book of Common Prayer, which was created under governmental direction and which was approved by Acts of Parliament in 1548 and 1549, set out in minute detail the accepted form and content of prayer and other religious ceremonies to be used in the established, tax supported Church of England. . . .

It is an unfortunate fact of history that, when some of the very groups which had most strenuously opposed the established Church of England found themselves sufficiently in control of colonial governments in this country to write their own prayers into law, they passed laws making their own religion the official religion of their respective colonies. Indeed, as late as the time of the Revolutionary War, there were established churches in at least eight of the thirteen former colonies and established religions in at least four of the other five. But the successful Revolution against English political domination was shortly followed by intense opposition to the practice of establishing religion by law. This opposition crystallized rapidly into an effective political force in Virginia, where the minority religious groups such as Presbyterians, Lutherans, Quakers and Baptists had gained such strength that the adherents to the established Episcopal Church were actually a minority themselves. In 1785–1786, those opposed to the established church, led by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, who, though themselves not members of any of these dissenting religious groups, opposed all religious establishments by law on grounds of principle, obtained the enactment of the famous “Virginia Bill for Religious Liberty” by which all religious groups were placed on an equal footing so far as the state was concerned. Similar though less far-reaching legislation was being considered and passed in other states.

By the time of the adoption of the Constitution, our history shows that there was a widespread awareness among many Americans of the dangers of a union of church and state. These people knew, some of them from bitter personal experience, that one of the greatest dangers to the freedom of the individual to worship in his own way lay in the government’s placing its official stamp of approval upon one particular kind of prayer or one particular form of religious services. They knew the anguish, hardship and bitter strife that could come when zealous religious groups struggled with one another to obtain the government’s stamp of approval from each king, queen, or protector that came to temporary power. The Constitution was intended to avert a part of this danger by leaving the government of this country in the hands of the people, rather than in the hands of any monarch. But this safeguard was not enough. Our Founders were no more willing to let the content of their prayers and their privilege of praying whenever they pleased be influenced by the ballot box than they were to let these vital matters of personal conscience depend upon the succession of monarchs. The First Amendment was added to the Constitution to stand as a guarantee that neither the power nor the prestige of the federal government would be used to control, support or influence the kinds of prayer the American people can say—that the people’s religions must not be subjected to the pressures of government for change each time a new political administration is elected to office. Under that Amendment’s prohibition against governmental establishment of religion, as reinforced by the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment, government in this country, be it state or federal, is without power to prescribe by law any particular form of prayer which is to be used as an official prayer in carrying on any program of governmentally sponsored religious activity.

There can be no doubt that New York’s state prayer program officially establishes the religious beliefs embodied in the regents’ prayer. The respondents’ argument to the contrary, which is largely based upon the contention that the regents’ prayer is “nondenominational” and the fact that the program, as modified and approved by state courts, does not require all pupils to recite the prayer, but permits those who wish to do so to remain silent or be excused from the room, ignores the essential nature of the program’s constitutional defects. Neither the fact that the prayer may be denominationally neutral nor the fact that its observance on the part of the students is voluntary can serve to free it from the limitations of the Establishment Clause, as it might from the Free Exercise Clause, of the First Amendment, both of which are operative against the states by virtue of the Fourteenth Amendment. Although these two clauses may, in certain instances, overlap, they forbid two quite different kinds of governmental encroachment upon religious freedom. The Establishment Clause, unlike the Free Exercise Clause, does not depend upon any showing of direct governmental compulsion and is violated by the enactment of laws which establish an official religion whether those laws operate directly to coerce nonobserving individuals or not. This is not to say, of course, that laws officially prescribing a particular form of religious worship do not involve coercion of such individuals. When the power, prestige and financial support of government is placed behind a particular religious belief, the indirect coercive pressure upon religious minorities to conform to the prevailing officially approved religion is plain. But the purposes underlying the Establishment Clause go much further than that. Its first and most immediate purpose rested on the belief that a union of government and religion tends to destroy government and to degrade religion. The history of governmentally established religion, both in England and in this country, showed that whenever government had allied itself with one particular form of religion, the inevitable result had been that it had incurred the hatred, disrespect and even contempt of those who held contrary beliefs. That same history showed that many people had lost their respect for any religion that had relied upon the support of government to spread its faith. The Establishment Clause thus stands as an expression of principle on the part of the Founders of our Constitution that religion is too personal, too sacred, too holy, to permit its “unhallowed perversion” by a civil magistrate. Another purpose of the Establishment Clause rested upon an awareness of the historical fact that governmentally established religions and religious persecutions go hand in hand. . . . And they knew that similar persecutions had received the sanction of law in several of the colonies in this country soon after the establishment of official religions in those colonies. It was in large part to get completely away from this sort of systematic religious persecution that the Founders brought into being our nation, our Constitution, and our Bill of Rights, with its prohibition against any governmental establishment of religion. The New York laws officially prescribing the regents’ prayer are inconsistent both with the purposes of the Establishment Clause and with the Establishment Clause itself.

It has been argued that to apply the Constitution in such a way as to prohibit state laws respecting an establishment of religious services in public schools is to indicate a hostility toward religion or toward prayer. Nothing, of course, could be more wrong. The history of man is inseparable from the history of religion. And perhaps it is not too much to say that, since the beginning of that history, many people have devoutly believed that “More things are wrought by prayer than this world dreams of.” It was doubtless largely due to men who believed this that there grew up a sentiment that caused men to leave the cross-currents of officially established state religions and religious persecution in Europe and come to this country filled with the hope that they could find a place in which they could pray when they pleased to the God of their faith in the language they chose. And there were men of this same faith in the power of prayer who led the fight for adoption of our Constitution and also for our Bill of Rights with the very guarantees of religious freedom that forbid the sort of governmental activity which New York has attempted here. These men knew that the First Amendment, which tried to put an end to governmental control of religion and of prayer, was not written to destroy either. They knew, rather, that it was written to quiet well justified fears which nearly all of them felt arising out of an awareness that governments of the past had shackled men’s tongues to make them speak only the religious thoughts that government wanted them to speak and to pray only to the God that government wanted them to pray to. It is neither sacrilegious nor anti-religious to say that each separate government in this country should stay out of the business of writing or sanctioning official prayers and leave that purely religious function to the people themselves and to those the people choose to look to for religious guidance.[3]

It is true that New York’s establishment of its regents’ prayer as an officially approved religious doctrine of that state does not amount to a total establishment of one particular religious sect to the exclusion of all others—that, indeed, the governmental endorsement of that prayer seems relatively insignificant when compared to the governmental encroachments upon religion which were commonplace 200 years ago. To those who may subscribe to the view that, because the regents’ official prayer is so brief and general there can be no danger to religious freedom in its governmental establishment, however, it may be appropriate to say in the words of James Madison, the author of the First Amendment:

[I]t is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties. . . . Who does not see that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other sects? That the same authority which can force a citizen to contribute three pence only of his property for the support of any one establishment may force him to conform to any other establishment in all cases whatsoever?

The judgment of the Court of Appeals of New York is reversed, and the cause remanded[4] for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

- 1. Ed. note: the defendant in a law suit

- 2. Ed. note: a Latin word meaning “to be informed” or “we wish to be informed,” certiorari is an order of a higher court to review a lower court decision. “Certiorari” was the first word of such orders when they were written in Latin.

- 3. There is, of course, nothing in the decision reached here that is inconsistent with the fact that school children and others are officially encouraged to express love for our country by reciting historical documents such as the Declaration of Independence which contain references to the Deity or by singing officially espoused anthems which include the composer's professions of faith in a Supreme Being, or with the fact that there are many manifestations in our public life of belief in God. Such patriotic or ceremonial occasions bear no true resemblance to the unquestioned religious exercise that the State of New York has sponsored in this instance.

- 4. Ed. note: returned to a lower court for reconsideration

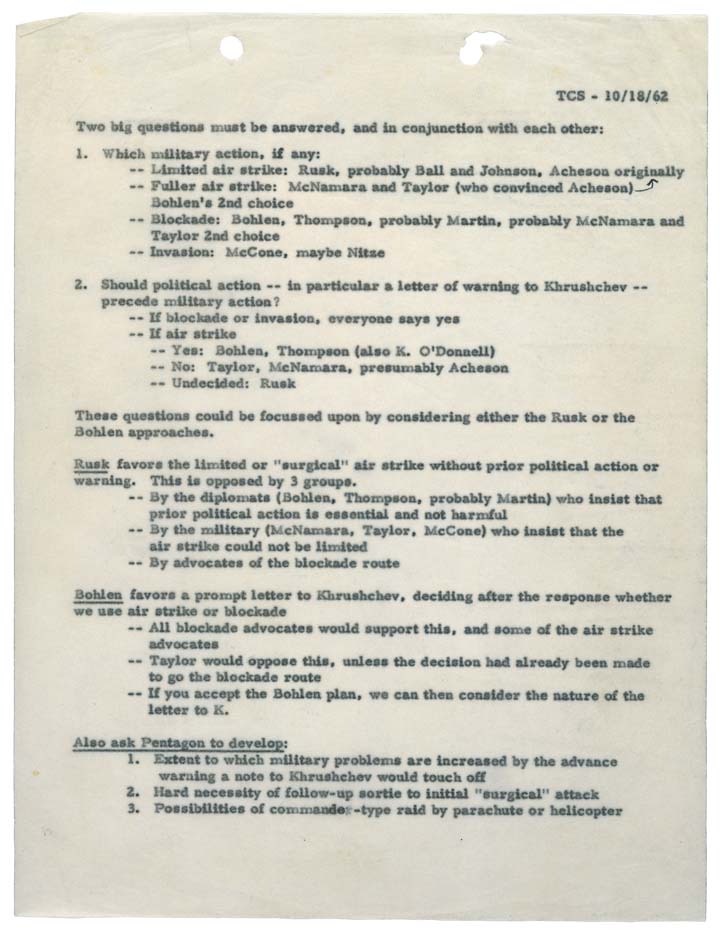

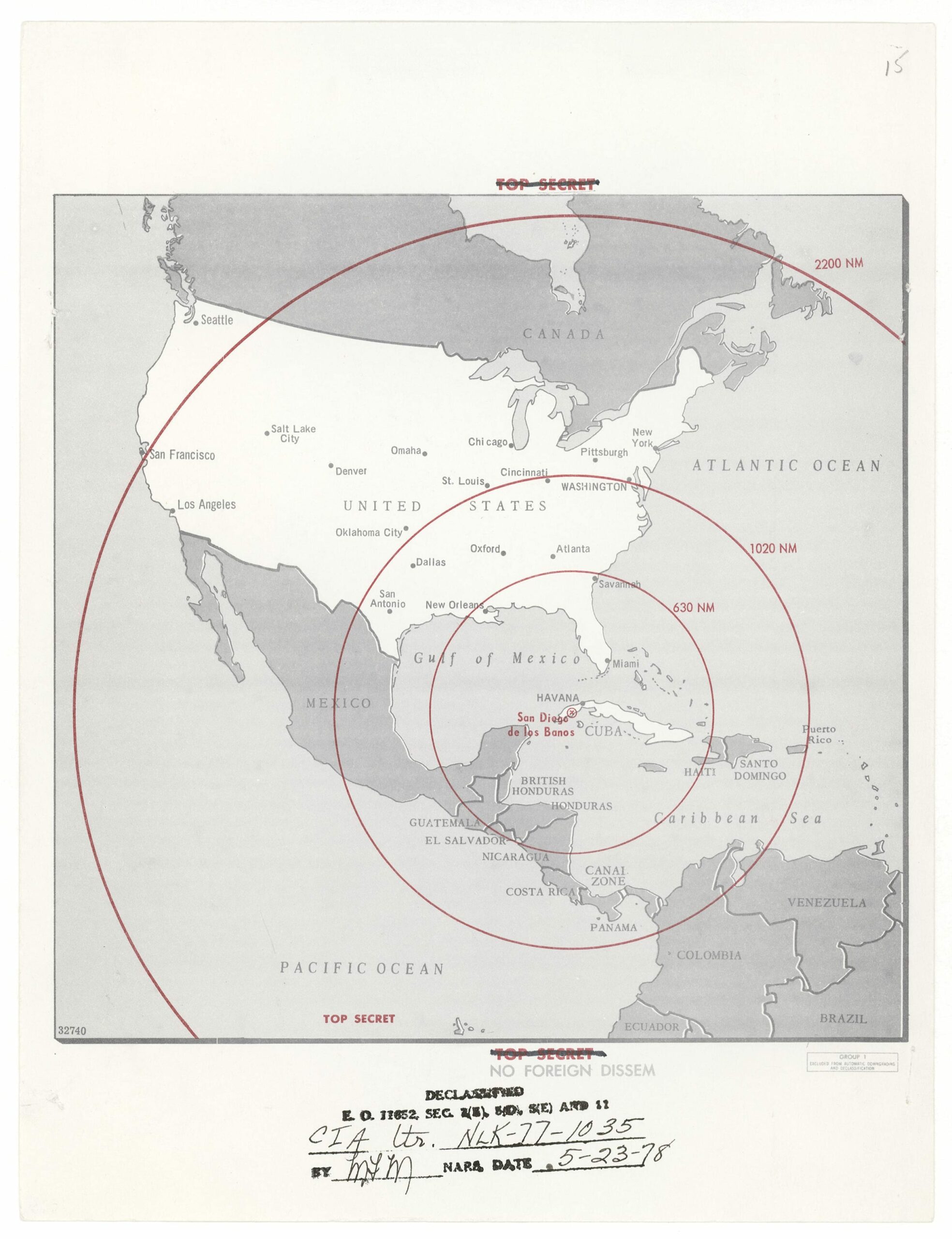

Statement on Cuba

September 04, 1962

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.