The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) between Great Britain and France, also known as the French and Indian War, was mostly fought over control of the North American colonies. Most American colonists sided with the British, with many taking up arms in defense of the Crown. After the conflict ended, Great Britain’s victory left it saddled with an enormous debt. To raise revenue, Parliament began imposing taxes on the British North American colonies, starting with the Stamp Act of 1765. The colonists strongly opposed the tax, arguing that the power of the purse in America resided in the colonial assemblies, not Parliament. The ensuing debate over representation and Parliament’s power, including some acts of violence, escalated until shots were exchanged between British troops and American militia in Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. Even after that skirmish, the Second Continental Congress sent King George III (1738–1820) the Olive Branch Petition pledging loyalty to the Crown and pleading with him to establish a “happy and permanent reconciliation.” King George’s response was to declare the colonies in “open and avowed rebellion” and commit his military to defeating the rebels.

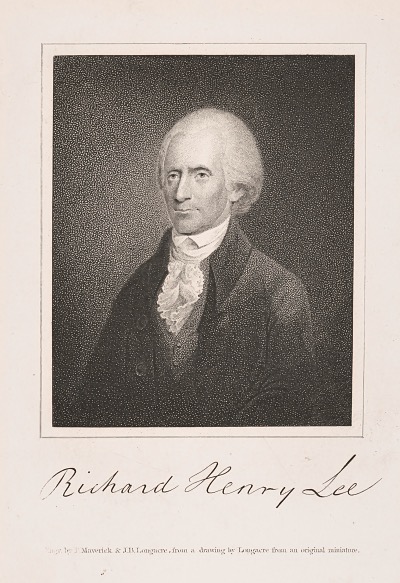

On June 7, 1776, acting on instructions from the Virginia convention that had selected him as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Richard Henry Lee (1732–1794) introduced a resolution calling for the colonies’ independence from Great Britain, for establishing alliances with other nations, and for a new plan for joint colonial government. Congress formed a committee to draft a Declaration of Independence if Congress adopted Lee’s resolution. Congress voted for independence on July 2nd and approved the formal Declaration of Independence on July 4th.