No study questions

No related resources

The conceptions of history have been almost as numerous as the men who have written history. To Augustine Birrel history is a pageant; it is for the purpose of satisfying our curiosity. Under the touch of a literary artist the past is to become living again. Like another Prospero the historian waves his wand, and the deserted streets of Palmyra sound of the tread of artisan and officer, warrior gives battle to generations that have long ago gone down to dust comes to life again in the pages of a book. The artistic prose narration of past events — this is the ideal of those who view history as literature. To this class belong romantic literary artists who strive to give to history the coloring and dramatic action of fiction, who do not hesitate to paint a character blacker or whiter than he really was, in order that the interest of the page may be increased, who force dull facts into vivacity, who create impressive situations, who, in short, strive to realize as an ideal the success of Walter Scott. It is of the historian Froude that Freeman says: “The most winning style, the choicest metaphors, the neatest phrases from foreign tongues would all be thrown away if they were devoted to proving that any two sides of a triangle are not always greater than the third side. When they are devoted to prove that a man cut off his wife’s head one day and married her maid the next morning out of sheer love for his country, they win believers for the paradox.” It is of the reader of this kind of history that Seely writes: “To him by some magic parliamentary debates shall always be lively, officials always men of strongly marked interesting character. There shall be nothing to remind him of the blue-book or the law book, nothing common or prosaic but he shall sit as in a theater and gaze at splendid scenery and costume. He shall never be called upon to study or to judge, but only to imagine and enjoy. His reflections as he reads shall be precisely those of the novel reader; he shall ask: Is this character well drawn? Is it really amusing? Is the interest of the story well sustained? And does it rise properly toward the close?”

But after all these criticisms we may gladly admit that in itself an interesting style, even a picturesque manner of presentation, is not to be condemned, provided that truthfulness of substance rather than vivacity of style be the end sought. But granting that a man by be the possessor of a good style which he does not allow to run away with him, either in the interest of the artistic impulse or the cause of party, still there remain differences as to the aim and method of history. To a whole school of writers among whom we find some of the great historians of our time, history is the study of politics, that is, politics in the high signification given the word by Aristotle, as meaning all that concerns the activity of the state itself. “History is past politics and politics present history,” says the great author of the Norman Conquest. Maurenbrecher, of Leipsic, speaks in no less uncertain tones; “The bloom of historical studies is the history of politics”; and Lorenz, of Jena, asserts: “The proper field of historical investigation, in the closer sense of the word, is politics.” Says Seeley: “The modern historian works at the same task as Aristotle in his politics.” “To study history is to study not merely a narrative but at the same time certain theoretical studies.” “To study history is to study problems.” And thus a great circle of profound investigators, with true scientific method, have expounded the evolution of political institutions, studying their growth as the biologist might study seed, bud, blossom and fruit. The results of these labors may be seen in such monumental works as those of Waitz on German institutions, Stubbs on English Constitutional History and Maine on Early Institutions.

There is another and an increasing class of historians to whom history is the study of the economic growth of the people, who aim to show that property, the distribution of wealth, the social condition of the people, are the underlying and determining factors to be studied. This school, whose advance-guard was led by Roscher, having already transformed orthodox political economy by its historical method, is now going on to rewrite history from the economic point of view. Perhaps the best English expression of the ideas of the school is to be found in Thorold Rogers’ “Economic Interpretation of History.” He truly asserts that “very often the cause of great political events and great social movements is economical and has hitherto been undetected.” So important does the fundamental principle of this school appear to me that I desire to quote from Mr. Rogers a specific illustration of this new historical method.

“In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries,” he says, “there were numerous and well frequented routes from the markets of Hindostan to the Western world, and for the conveyance of that Eastern produce which was so greatly desired as a seasoning to the coarse and often unwholesome diet of our forefathers. The principal ports to which this produce was conveyed were Seleucia (latterly called Licia) in the Levant, to Trebizond, on the Black Sea, and to Alexandria. From these ports this Eastern produce was collected mainly by the Venetian and Genoese traders, and conveyed over the passes of the Alps to the upper Danube and the Rhine. The stream of commerce was not deep or broad, but it was singularly fertilizing, and every one who has any knowledge of the only history worth knowing, knows how important these cities were in the later Middle Ages.

“In the course of time, all but one of these routes had been blocked by the savages who desolated Central Asia, and still desolate it. It was, therefore, the object of the most enterprising of the Western nations to get, if possible, in the rear of these destructive brigands, by discovering a long sea passage to Hindostan, All Eastern trade depended on the Egyptian road being kept open, and this remaining road was already threatened. The beginning of this discovery was the work of a Portuguese prince. The expedition of Columbus was an attempt to discover a passage to India over the Western sea. By a curious coincidence the Cape passage was doubled, and the new world discovered almost simultaneously.

“The discoveries were made none too soon. Selim I (1512-1520) the sultan of Turkey conquered Mesopotamia and the holy towns of Arabia, and annexed Egypt during his brief reign. This conquest blocked the only remaining road which the Old World knew. The thriving manufacturers of Alexandria were at once destroyed. Egypt ceased to be the highway from Hindostan, I discovered that some cause must be at work which had hitherto been unsuspected in the sudden and enormous rise of prices in all Eastern products, at the close of the first quarter of the sixteenth century, and found that it must have come from the conquest of Egypt. The river of commerce was speedily dried up. The cities which had thriven on it were gradually ruined, at least in so far as this source of their wealth was concerned, and the trade of the Danube and Rhine ceased, The Italian cities fell into rapid decay. The German nobles who had got themselves incorporated among the burghers’ of the free cities, were impoverished, and betook themselves to the obvious expedient of reimbursing their losses by the pillage of their tenants. Then came the Peasants’ war, its ferocious incidents, its cruel suppression, and the development of those wild sects which disfigured and arrested the German Reformation. The battle of the Pyramids, in which Selim gained the Sultanate of Egypt for the Osmanli Turks, brought loss and misery into thousands of homes where the event had never been heard of. It is such facts as these which the economic interpretation of history illustrates and expounds.”

Viewed from this position, the past is filled with new meaning. The focal point of modern interest is the fourth estate, the great mass of the people. History has been a romance and a tragedy. In it we read the brilliant annals of the few. The intrigues of courts, knightly valor, palaces and pyramids, the loves of ladies, the songs of minstrels, and the chants from cathedrals, pass like a pageant, or linger like a strain of music as we turn the pages. But history has its tragedy as well, which tells of the degraded tillers of the soil, toiling that others might dream, the slavery that rendered possible the “glory that was Greece,” the serfdom into which decayed the “grandeur that was Rome”— these as well demand their annals. Far oftener than has yet been shown have these underlying economic facts affecting the breadwinners of the nation, been the secret of the nation’s rise of fall, by the side of which much has been the secret of the nation’s rise or fall, by the side of which much that has passed as history is the merest frippery.

But I must not attempt to exhaust the list of the conceptions of history. To a large class of writers represented by Hume, the field of historical writing is an arena whereon are to be fought out present partisan debates. Whig is to struggle against Troy, and the party of the writers choice is to be victorious at whatever cost to the truth. We do not lack these partisan historians in America. To Carlyle, the hero-worshipper, history is the stage on which a few great men play their parts. To Max Muller, history is the text whereby to teach a lesson. To the metaphysician history is the fulfillment of a few primary laws.

Plainly we may make choice out of many ideals. If, now, we strive to reduce them to some kind of order, we find that in each age a different ideal of history is prevailed. To the savage history is the painted scalp, with its symbolic representations of the victims of his valor; or it is the legend of the gods and heroes of his race — attempts to explain the origin of things. Hence the vast body of mythologies, folk-lore and legends, in which science, history, fiction, are all blended together, judgment and imagination inextricably confused. As time passes the artistic instinct comes in and historical writing takes the form of Iliad, or Niebelungen Lied. Still we have in these writings the reflections of the imaginative, credulous age that believed in the divinity of its heroes and wrote down what it believed. Artistic and critical faculty find expression in Herodotus, father of Greek history, and in Thucydides, the ideal Greek historian. Both write from the standpoint pf an advanced civilization and strive to present a real picture of the events and an explanation of the causes of the events. But Thucydides is a Greek; literature is to him an art, and history a part of literature; and so it seems to him no violation of historical truth to make his generals pronounce long orations that were composed for them by the historian. Moreover early men and Greeks alike believed their own tribe or state to be the favored of the gods: the rest of humanity was for the most part outside the range of history.

To the medieval historian history was the annuals of the monastery, or the chronicle of court and camp.

In the nineteenth century a new ideal and method of history arose. Philosophy prepared the way for it. Schelling taught the doctrine “that the state is not in reality governed by laws of man’s devising, but is a part of the moral order of the universe, ruled by cosmic forces from above.” Herder proclaimed the doctrine of growth in human institutions. He saw in history the development of given germs; religions were to be studied by comparison and by tracing their origins from superstition up toward rations conceptions of God. Language, too, was no sudden creation, but a growth and to be studied as such; and so with political institutions. Thus he paved the way for the study of comparative philology, and of political evolution. Wolfe, applying herder’s suggestions to the Iliad, found no single Homer as its author, but many. This led to the critical study of the texts. Niebuhr applied this mode of study to the Roman historians and proved their incorrectness. Livy’s history of early Rome became legend. Then Niebuhr tried to find the real facts. He believed that, although the Romans had forgotten their own history, still it was possible by starting with institutions of known reality to construct their predecessors, as the botanist may infer bud from flower. He would trace causes from effects. In other words, so strongly did he believe in the growth of an institution according to fixed laws that he believed he could reconstruct the past, reaching the real facts even by means of the incorrect accounts of the Roman writers. Although he carried his method too far, still it was the foundation of the modern historical school. He strove to reconstruct old Rome as it really was out of the original authorities that remained. By critical analysis and interpretation he attempted so to use these texts that the buried truth should come to light. To skill as an antiquary he added great political insight — for Niebuhr was a practical statesmen. It was his aim to unite critical study of the materials with the interpretative skill of the political expert and this has been the aim of the new school of historians. Leopold von Ranke applied this critical method to the study of modern history. To him a document surviving from the past itself was of far greater value than any amount of tradition regarding the past. To him the contemporary account, rightly used, was of far higher authority than the second-hand relation. And so he diligently sought in the must archives of European courts, and the results of his labors and those of his scholars have been the rewriting of modern diplomatic and political history. Charters, correspondence, contemporary chronicles, inscriptions — these are the materials on which he and his disciples worked. To “tell things as they really were” was Ranke’s ideal. But to him also, history was primarily past politics.

Superficial and hasty as this review has been, I think you see that the historical study of the first half of the nineteenth century reflected the thought of that age. It was an age of political agitation and inquiry, as our own age still so largely is. It was an age of science. That inductive study of phenomena which has worked a revolution in our knowledge of the external world and applied to history. In a word the study of history became scientific and political.

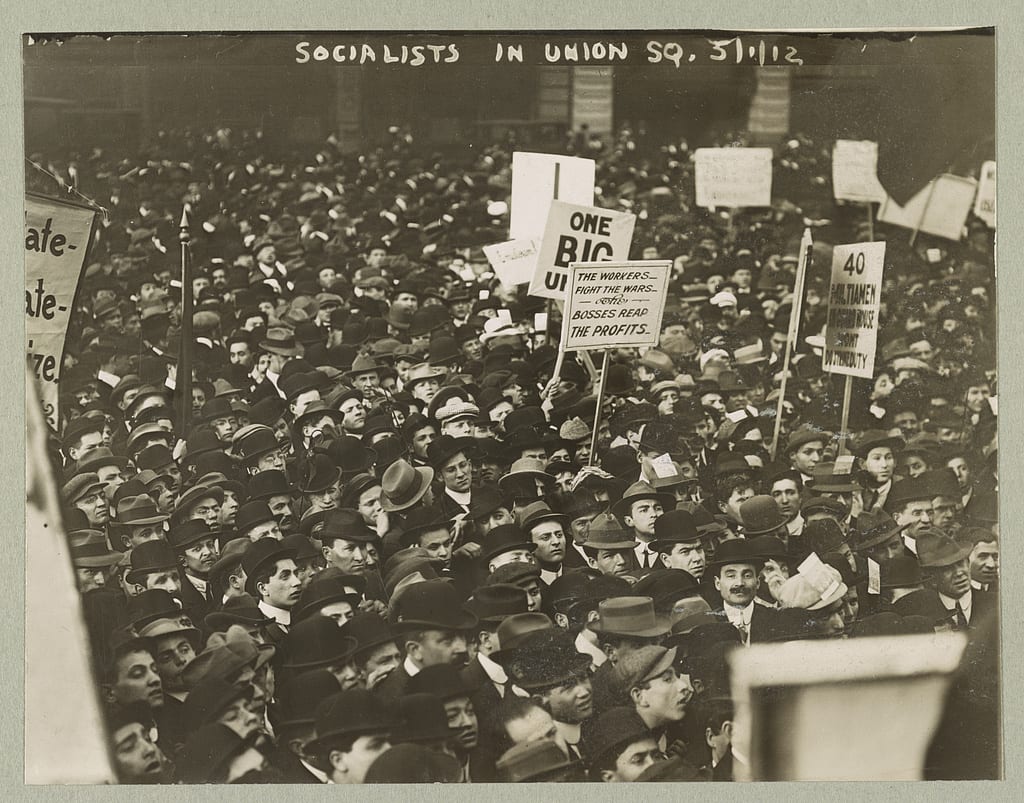

Today the questions that are uppermost, and that will become increasingly important, are not so much political as economic questions. The age of machinery, of the factory system, is also the age of socialistic inquiry.

It is not strange that the predominant historical study is coming to be the study of past social conditions, inquiry as to land-holding, distribution of wealth and the economic basis of society in general. Our conclusion, therefore is, that there is much truth in all these conceptions of history: history is past literature, it is past politics, it is past religion, it is past economics.

Each age tries to form its own conception of the past. Each age writes the history of the past anew with reference to the conditions uppermost in its own time. Historians have accepted the doctrine of Herder. Society grows. They have accepted the doctrine of Comte. Society is an organism. History is the biography of society in all of its departments. There is objective history and subjective history. Objective history applies to the events themselves; subjective history is man’s conception of these events. “The whole mode and manner of looking at things alters with every age,” but this does not mean that the real events of a given age change: it means that our comprehension of these facts changes.

History, both objective and subjective, is ever becoming — never completed. The centuries unfold to us more and more the meaning of past times. Today we understand Roman history better than did Livy or Tacitus; not only because we know how to use sources better, but also because the significance of events develops with time; because today is so much a product of yesterday that yesterday can only be understood as explained by today. The aim of history, then, is to know the elements of the present by understanding what came into the present from the past. For the present is simply the developing past, the past the undeveloped present. As well try to understand the egg without a knowledge of its developed form, the chick, as to try to understand the past without bringing to it the explanation of the present; and equally as well try to understand an animal without study of its embryology as to try to understand one time without the study of events that went before. The antiquarian strives to bring back the past for the sake of the past; the historian strives to show the present to itself by revealing its origin from the past. The goal of the antiquarian is the dead past: the goal of the historian is the living present. Droysen has put this true conception into the statement: “History is the “know thyself of humanity” — “the self consciousness of mankind.”

If now, you accept with me the statement of this great master of historical science, the rest of our way is clear. If history be, in truth, the self consciousness of humanity, the “self consciousness of the living age, acquired by understanding its development from the past,” all the rest follows.

First we recognize why all the spheres of man’s activity must be considered. Not only is this the only way in which we can get a complete view of the society, but no one department of social life can be understood in isolation from the others. The economic life and the political life touch, modify and condition one another. Even the religious life needs to be studied in conjunction with the political and economic life, and vice versa. Therefore all kinds of history are essential — history as politics, history as art, history as economics, history as religion — all are truly parts of society’s endeavor to understand itself by understanding its past.

Next, we see that history is not shut up in a book — not in many books. The first lesson the student of history has to learn is to discard his conception that there are standard ultimate histories. In the nature of the case this is impossible. History is all the remains that have come down to us from the past, studied with all the critical and interpretative power that the present can bring to the task. From time to time great masters bring their investigations to fruit in books. To us these serve as the latest words, the best results of the most recent efforts of historian the materials for his work are found in all that remains from the ages gone by — in papers, roads, mounds, customs, languages; in monuments, coins, medals, names, titles, inscriptions, charters; in contemporary annals and chronicles, and finally in the secondary sources or histories in the common acceptance of the term. Wherever there remains a chipped flint, a spear-head, a piece of pottery, a pyramid, a picture, a poem, a colosseum, or a coin, there is history. Says Taine:

“What is your first remark on turning over the great stiff leaves of a folio, the yellow sheets of a manuscript, a poem, a code of laws, a declaration of faith? This you say was not created alone. It is but a mould, like a fossil shell, an imprint like one of those shapes embossed in stone by an animal which lived and perished. Under the shell there was an animal, and behind the document there was a man. Why do you study the shell except to represent to yourself the animal? So do you study the document only in order to know the man. The shell and the document are lifeless wrecks, valuable only as a clue to the entire and living existence. We must reach back to this existence, endeavor to re-create it.”

But observe that when a man writes a narration of the past, he writes with all his limitations as regards ability to test the real value of his sources, and as able rightly to interpret them. Does he make use of a chronicle? First he must determine whether it is genuine; then whether it was contemporary, or at what period written; then what opportunities its author had to know the truth; then what were his personal traits; was he likely to see clearly to relate impartially? If not, what was his bias, what his limitations? Next comes the harder task — to interpret the significance of events’ causes must be understood, results seen. Local affairs must be described in relations to affairs of the world — all must be told with just selection, emphasis, perspective; with that historical imagination and sympathy that does not judge the past by the canons of the present, nor read into it the ideas of the present. Above all the historian must have a passion for truth above that for any party or idea. Such are some of the difficulties that lie in the way of our science. When, moreover, we consider that each man is conditioned by the age in which he lives and must perforce write with limitations and prepossessions, I think we shall all agree that no historian can say the ultimate word.

Another thought that follows as a corollary from our definition is, that in history there is a unity and a continuity. Strictly speaking there is no gap between ancient, medieval and modern history. Strictly speaking there are no such divisions. Baron Bunsen dates modern history from the migration of Abraham. Bluntschli makes it begin with Frederick the great. The truth is, as Freeman has shown, that the age of Pericles, or the age of Augustus has more in common with modern times than has the age of Alfred or of Charlemagne. There is another test than that of chronology; namely, stages of families into states, from peasantry into the complexity of great city life, from animism into monotheism, from mythology into philosophy; and have yielded place again to primitive people who in turn have passed through stages like these and yielded to new nations. Each nation has bequeathed something to its successor; no age has suffered the highest content of the past entirely to be lost. By unconscious inheritance, and by conscious striving after the past as part of the present, history has acquired continuity. Freeman’s statement that into Rome flowed all the ancient world and out of Rome came the modern world is as true as it is impressive. In a strict sense imperial Rome never died. You may find the eternal city still living in the Kaizer and the Czar, in the language of the Romance peoples, in the codes of European states, in the eagles of their coats of arms, in every college where the classics are read in a thousand political institutions. Even here in young America old Rome still lives. When the inaugural procession passes toward the senate chamber, and the president’s address outlines the policy he proposes to pursue there is Rome! You may find her in the code of Louisiana, in the French and Spanish portions of our history, in the idea of checks and balances in our constitution. Clearest of all, Rome may be seen in the titles, government, and ceremonials of the Roman Catholic church; for when the Caesar passed away, his scepter fell to that new Pontifex Maximus, the Pope, and to that new Augustus, the Holy Roman Emperor of the Middle Ages, an empire which in name, or at least, continued till those heroic times when a new Imperator recalled the days of the great Julius, and sent the eagles of France to proclaim that Napoleon was king over kings. So it is true in fact, as we should presume, a priori, that to history there are only artificial divisions. Society is an organism, ever growing. History is the self-consciousness of this organism. “The roots of the present lie deep in the past.” There is no break. But not only is it true that no country can be understood without taking account of all the past; it is also true that we cannot select a stretch of land and say we will limit our study to this land; for local history can only be understood in the light of the history of the world. There is unity as well as continuity. To know the history of contemporary Italy, we must know the history of contemporary France, of contemporary Germany. Each acts on each. Ideas, commodities even, refuse the bounds of a nation. All are inextricably connected, so that each is needed to explain the others. This is true especially of our modern world with its complex commerce and means of intellectual connection. In history, then, there is unity and continuity. Each age must be studied in the light of all the past; local history must be viewed in the light of world-history.

Now, I think we are in a position to consider the utility of historical studies. I will not dwell on the dignity of history considered as the self-consciousness of humanity; nor on the mental growth that comes from such a discipline; nor on the vastness of the field — all these occur to you, and their importance will impress you increasingly as you consider history from this point of view. To enable us to behold our own time and place as a part of the stupendous progress of the ages — to see primitive man; to recognize in our midst the undying ideas of Greece; to find Rome’s majesty and power alive in present law and institution, still living in our superstitions and our folk-lore; to enable us to realize the richness of our inheritance, the possibility of our lives, the grandeur of the present — these are some of the priceless services of history.

But I must conclude my remarks with a few words upon the utility of history as affording a training for good citizenship. Doubtless good citizenship is the end for which the public schools exist. Were it otherwise there might be difficulty in justifying the support of them at public expense. The direct and important utility of the study of history in the achievement of this end hardly needs argument.

In the union of public service and historical study, Germany has been pre-eminent, For certain governmental positions in that country, a university training in historical studies is essential. Ex-President Andrew D. White affirms that a main cause of the efficiency of German administration is the training that officials get from the university study of history and politics. In Paris there is the famous School of Political Sciences which fits men for the public service of France. In the decade closing with 1887 competitive examinations showed the advantages of this training. Of 60 candidates appointed to the council of state, 40 were graduates of this school. Of 42 appointed to the inspection of finance, 39 were from the school; 16 of 17 appointees to the court of claims, and 20 of 26 appointees to the department of foreign affairs held from the School of Political Sciences. In these European countries not merely are the departmental officers required to possess historical training; the list of leading statesmen reveals many names eminent in historical science. I need hardly recall to you the great names of Niebuhr, the councilor, whose history of Rome gave the impetus to our new science; of Stein, the reconstructor of Germany, and the projector of the Monumenta Germanicae, that priceless collection of original sources of medieval history. Read the roll of Germany’s great public servants and you will find among them such eminent men as Gneist, the authority on English constitutional history; Bluntschli, the able historian of politics; von Holst, the historian of our own political development; Knies, Roscher and Wagner, the economists, and many more, I have given you Droysen’s conception of history, but Droysen was not simply a historian, he belonged with the famous historians, Treitschke, Mommsen, von Sybel, to what Lord Acton calls “that central band of writers and statesmen and soldiers, who turned the tide that had run for six hundred years, and conquered the centrifugal forces that had reigned in Germany longer than the commons have sat at Westminster.”

Nor does England fail to recognize the value of the union of history and politics as exemplified by such men as Macaulay, Dilke, Morley and Bryce, all of whom have been eminent members of parliament, as well as distinguished historical writers. From France and Italy such illustrations could easily be multiplied.

When we turn to America and ask what marriages have occurred between history and statesmanship, we are filled with astonishment at the contrast. It is true that our country has tried to reward literary men: Motley, Irving, Bancroft, Lowell held official positions, but these positions were in the diplomatic service. The “literary fellow” was good enough for Europe. The state gave these men aid rather than called their services to its aid. To this statement I know of but one important exception — George Bancroft. In America statesmanship has been considered something of spontaneous generation, a miraculous birth from our republican institutions. To demand of the statesmen who debate such topics as the tariff, European and South American relations, emigration, the labor and the railroad problems, a scientific acquaintance with historical politics or economics, would be to expose one’s self to ridicule in the eyes of the public. I have said that the tribal stage of society demands tribal history and tribal politics. When a society is isolated it looks with contempt upon the history and institutions of the rest of the world. We shall not be altogether wrong if we say that such tribal ideas concerning our institutions and society have prevailed for many years in this country. Lately historians have turned to the comparative and historical study of our political institutions. The actual working of our constitution as contrasted with the literary theory of it has engaged the attention of able young men. Foreigners like von Holst and Bryce have shown us a mirror of our political life in the light of the political life of other peoples. Little of this influence has yet attracted the attention of our public men. Count the roll in Senate and House, Cabinet and diplomatic service — to say nothing of the state governments and where are the names famous in history and politics? It is shallow to express satisfaction with this condition, and sneer at “literary fellows.” To me it seems that we are approaching a pivotal point in our country’s history.

In an earlier part of my remarks I quoted from Thorold Rogers showing how the Turkish conquest of far off Egypt brought ruin to homes in Antwerp and Bruges. If this was true in that early day, when commercial threads were infinitely less complex than they are now, how profoundly is our present life interlocked with the evens of all the world. Heretofore America had measurably remained aloof from the Old World affairs. Under the influence of a wise policy, she has avoided political relations with other powers. But is one of the profoundest lessons that history has to teach, that political relations, in a highly developed civilization, are inextricably connected with economic relations. Already there are signs of a relaxation of our policy of commercial isolation. Reciprocity is a word that meets with increasing favor from all parties. But, once fully afloat on the sea of world-wide economic interests, we shall soon develop political interests. Our fishery disputes furnish one example; our Samoan interest another; our Congo relations a third. But, perhaps, most important are our present and further relations with South America coupled with our Monroe doctrine. It is a settled maxim of International law that the government of a foreign state whose subjects have lent money to another state may interfere to protect the rights of the bondholders, if they are endangered by the borrowing state. As Prof. H. B. Adams has pointed out, South American states have close financial relations with many European money-lenders; they are also prone to revolutions. Suppose, now, that England, finding the interests of her bondholders in jeopardy, should step in to manage the affairs of some South American country as she has those of Egypt for the same reason. Would the United States abandon its popular interpretation of the Monroe doctrine, or would she give up her policy of non-interference in political affairs of the outer world? Or suppose our own bondholders in New York, say, to be in danger of loss by revolution in South America —and our increasing tendency to close connection with South American affairs makes this a supposable case — would our government stand idly by while her citizens’ interests were sacrificed? Take another case, the protectorate of the proposed inter-oceanic canal. England will not be content to allow the control of this to rest solely in our hands. Will the United States form an alliance with England for the purpose of this protection? Such questions as these indicate that we are drifting out into European political relations; and that a new statesmanship is demanded; a statesmanship that shall clearly understand European history and present relations which depend on history. Again, consider the problems of socialism brought to our shores by European immigrants. We shall never deal rightly with such problems until we understand the historical conditions under which they grew. Thus we not only meet Europe outside our borders, but in our very midst. The problem of immigration furnishes many examples of the need of historical study. Consider how our vast western domain has been settled. Louis XIV devastates the Palatinate, and soon hundreds of its inhabitants are hewing down the forests of Pennsylvania. The bishop of Salsburg persecutes his Protestant subjects, and the woods of Georgia sound to the crack of Teutonic rifles. Presbyterians are oppressed in Ireland, and soon in Tennessee and Kentucky the fires of pioneers gleam. These were but advance-guards of the mighty army that has poured into our midst ever since. Every economic change, every political change, every military conscription, every socialistic agitation in Europe has sent ups groups of colonists who have passed out on to our prairies to form new self-governing communities, or who have entered the life of our great cities. These men have come to us historical products, they have brought to us, not merely so much bone and sinew, not merely so much money, not merely so much manual skill — they have brought with them deep-inrooted customs and ideas. They are important factors in the political and economic life of the nation. Our destiny is interwoven with theirs; how shall we understand American history, without understand European history? The story of the peopling of America has not yet been written. We do not understand ourselves.

One of the most fruitful fields of study in our country has been the process of growth of our own institutions, local and national. The town and the county, the germs of our political institutions, have been traced back to old Teutonic roots. Gladstones’ remark that “The American Constitution is the most wonderful work ever struck off at a given time by the brain and purpose of man,” has been shown to be misleading, for the Constitution was, with all the constructive powers of the fathers, still a growth; and our history is only to be understood as a growth from European history under the new conditions of the new world. Says Dr. H.B. Adams:

“American local history should be studied as a contribution to national history. This country will yet be viewed and reviewed as an organism of historic growth, developing from minute germs, from the very protoplasm of state-life. And some day this country will be studied in its international relations, as an organic part of a larger organism now vaguely called the World-State, but as surely developing through the operation of economic, legal, social and scientific forces as the American Union, the German and British Empires are evolving into higher forms.” “The local consciousness must be expanded into a fuller sense of its historic worth and dignity. We must understand the cosmopolitan relations of modern local life, and its own wholesome conservative power in these days of growing centralization.”

If any added argument were needed to show that good citizenship demands the careful study of history, it is in the examples and lessons that the history of other peoples has for us. It is profoundly true that each people makes its own history in accordance with its past. It is true that a purely artificial piece of legislation, unrelated to present and past conditions, is the most short-lived of things. Yet it is to be remembered that it was history that taught us this truth, and that there is, within the limits of the constructive action possible to a state, large scope for the use of this experience of foreign peoples.

I have aimed to offer, then, these considerations: History, I have said, is to be taken in now narrow sense. It is more than past literature, more than past politics, more than past economics. It is the self-consciousness of humanity-humanity’s effort to understand itself through the study of its past. Therefore it is not confined to books the subject is to be studied, not books simply. History has a unity and a continuity: the present needs the past to explain it; and local history must be read as a part of world history. The study has a utility as a mental discipline, and as expanding our ideas regarding the dignity of the present. But perhaps its most practical utility to us, as public school teachers, is its service in fostering good citizenship.

The ideals presented may at first be discouraging. Even to him who devotes his life to study of history the ideal conception is impossible of attainment. He must select some field and till that thoroughly — be absolute master of it; for the rest he must seek the aid of others whose lives have been given in the true scientific spirit of the study of special fields. The public school teacher must do the best with the libraries as his disposal. We teachers must use all the resources we can obtain and not pin our faith to a single book; we must make history living instead of allowing it to seem mere literature, a mere narration of events that might have occurred in the mood. We must teach the history of a few countries thoroughly, rather than that of many countries superficially. The popularizing of scientific knowledge is one of the best achievements of this age of book-making. It is typical of that social impulse which has led university men to bring the fruits of their study home to the people. In England the social impulse has let to what is known as the university extension movement. University men have left their traditional cloister, and gone to live among the working classes, in order to bring to them a new intellectual life. Chautauqua, in our own country, has begun to pass beyond the period of superficial work to real union of the scientific and the popular. In their summer school they offer courses in American history. Our own State university carries on extensive work in various lines. I believe that this movement in the direction of popularizing historical and scientific knowledge will work a real revolution in our towns and villages as well as in our great cities. The school teacher is called to do a work above and beyond the instruction in his school. He is called upon to be the apostle of the higher culture to the community in which he is placed. Given a good school or town library — such an one is now within the reach of every hamlet that is properly stimulated to the acquisition of one — and given an energetic, devoted teacher to direct and foster the study of history and politics and economics, and we would have an intellectual regeneration of the state. Historical study has for its end to let the community see itself in the light of the past — to give it new thoughts and feelings, new aspirations and energies. Thoughts and feelings flow into deeds. Here is the motive-power that lies behind institutions. This is therefore one of the ways to create good politics; here we can tough the very “age and body of the time. Its form and pressure.” Have you a thought of better things, a reform to accomplish? “Put it in the air,” says the great teacher. Ideas have ruled, will rule. We must make university-extension into state life felt in this country as did Germany. Of one thing beware. Avoid as the very unpardonable sin, any one-sidedness, any partisan, any partial treatment of history. Do not misinterpret the past for the sake of the present. The man who enters the temple of history must devoutly respond to that invocation of the church “Sursum corda ” — lift up your heart. No looking at history as an idle take, a compend of anecdotes; no servile devotion to a text book, no carelessness of truth about the dead that can no longer speak, must be permitted in its sanctuary. “History,” says Droysen, “is not the truth and the light; but a striving for it, a sermon on it, a consecration to it.”

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.