No related resources

Introduction

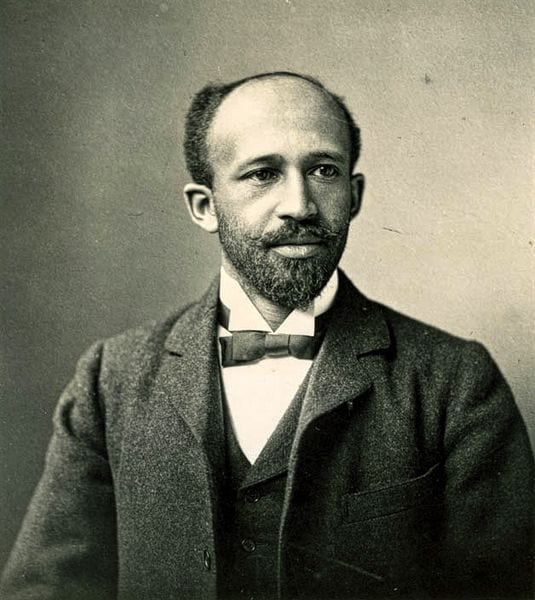

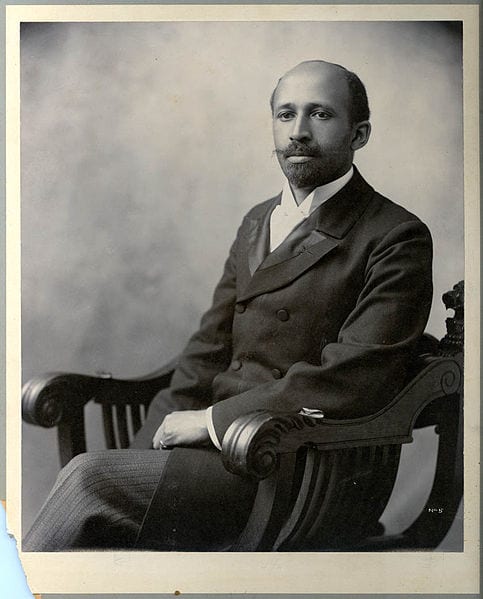

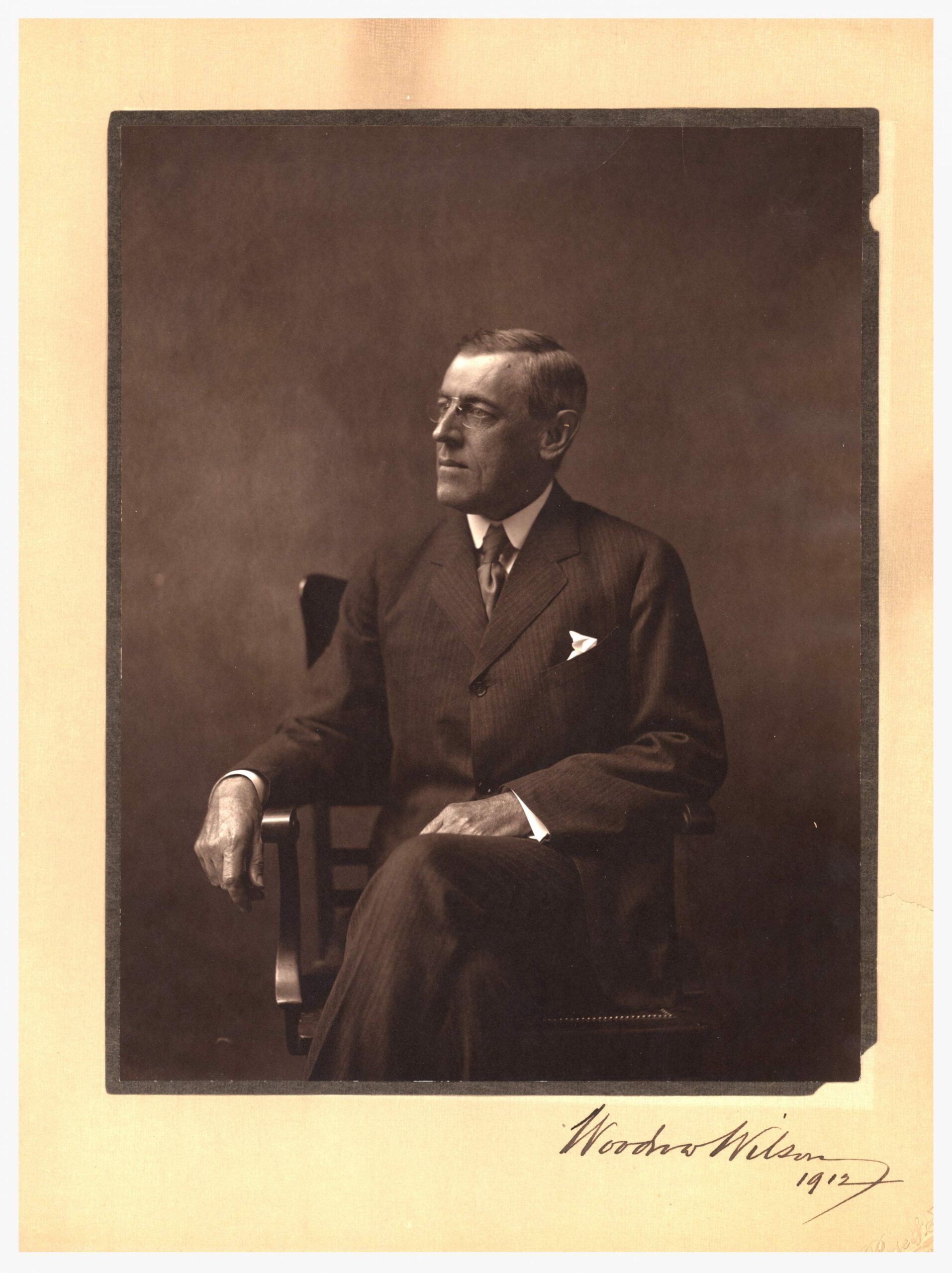

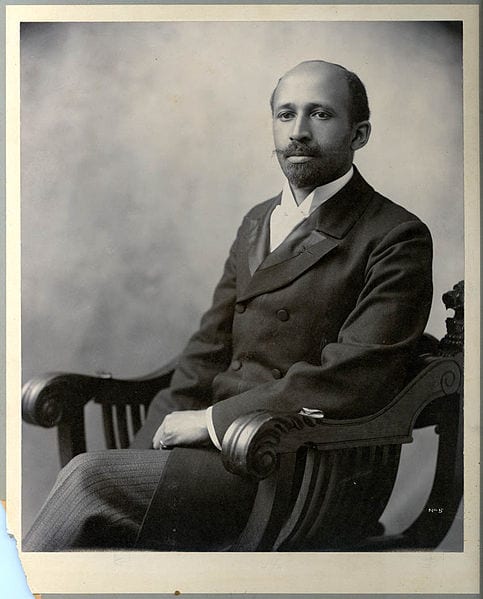

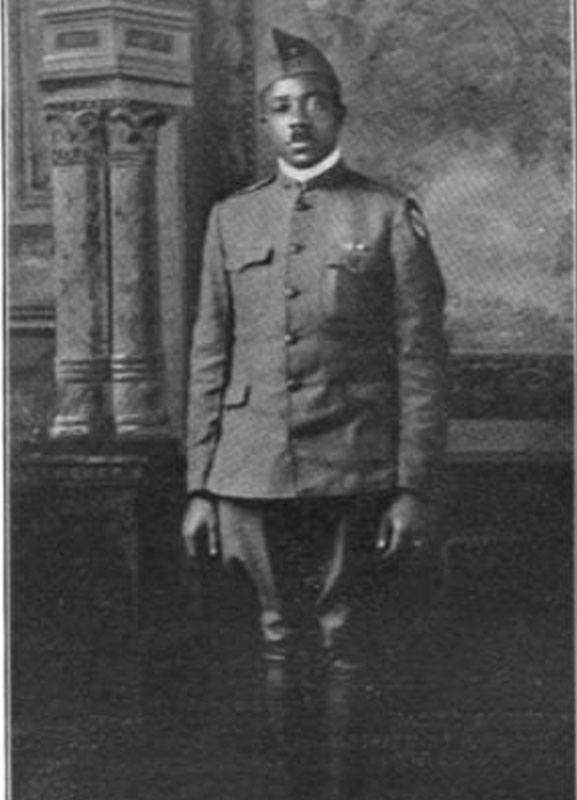

Charles R. Isum (1889–1941) was drafted in southern California and assigned to the medical detachment of the 1st Battalion, 365th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Division—the only fully functioning African American combatant division in the U.S. Army. Isum served in various sectors along the Western Front. A gas attack on November 10, 1918, permanently damaged his heart. Rather than dwelling on the injustice of being wounded the night before the Armistice went into effect, Isum focused his anger on the relentless racial discrimination he encountered in the Army. Upon returning home from France, Isum wrote this letter to civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) detailing a racially charged incident that illustrated the contrasting treatments he received from antagonistic white American officers and welcoming French civilians.

Isum worked as a bookbinder for the Los Angeles Times until his health deteriorated in the 1930s. He continued his activism, at one point suing a southern California restaurant for overcharging him (the restaurant had a higher-priced menu for African Americans). He imbued his children with the same drive to seek equal rights. His daughter, Rachel Isum, entered the nursing program at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and worked as a “Rosie the Riveter” at a Lockheed Aircraft factory in World War II. At UCLA, she began dating star athlete Jackie Robinson but promised her father that she would complete her studies before marrying. The couple wed in 1946, five years after Isum died. The Robinsons continued his legacy of activism with their own lifelong dedication to the civil rights movement that included Jackie joining the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 as the first Black player in Major League Baseball.

Letter from Charles R. Isum to W. E. B. Du Bois, May 17, 1919, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. Available at: http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b014-i219.

Dear Sir,

I have just finished reading the May issue of the CRISIS and have enjoyed it immensely.1 I am indeed pleased to note that someone has the nerve and backbone to tell the public the unvarnished facts concerning the injustice, discrimination and southern prejudices practiced by the white Americans against the Black Americans in France.

I am a recently discharged Sergeant of the Medical Detachment, 365th Infantry, 92nd Division, and I take this opportunity to relate one of my personal experiences with the southern rednecks who were in command of my division, brigade and regiment.

On or about December 26, 1918, General Order No. 40 was issued from the headquarters of the 92nd Division. I cannot recall the exact wording of the part of the order which was of a discriminating nature, but it read something to this effect, “Military Police will see that soldiers do not address, carry on conversation with or accompany the female inhabitants of this area.”2 At the time this order was issued we were billeted in the village of Ambrieres, Mayenne. There were white soldiers also billeted in the same village but they did not belong to the 92nd Division and the order did not affect them, hence it was an order for Colored3 soldiers only. It was not an A.E.F. order. It was a divisional order for Colored soldiers. We were living in the same houses with the French people and under the terms of this order we were forbidden to even speak to the people with whom we lived, while the white soldiers of the 325th Baking Co. and the Sub-supply Depot #10 were allowed to address, visit or accompany these same people where and whenever they desired.

On Jan. 21, 1919, Mademoiselle Marie Meziere, the eldest daughter of Monsieur Charles Meziere, a merchant tailor of Ambieres [sic] was married to Monsieur Maurice Barbe, a French soldier. I was invited to be a guest at the wine party, to accompany the bridal party on the marriage promenade and to be a guest at the supper, which was to take place at 8:30 p.m. I attended the party with a few other Colored soldiers from the Medical Detachment. No whites were invited but Capt. Willis (white) of the Supply Company “butted in.” He spoke miserable french [sic] and the members of the party called on the Colored soldiers to interpret for him. Willis became enraged and turned his back on the Colored boys and told the French people that it was improper for them to associate with the Black soldiers. The French people paid no attention to what he said and we all left him sitting in the cafe alone. His temperature at this time was about 104 degrees. The other Colored soldiers returned to the Infirmary and I accompanied the bridal party on the promenade out on the boulevard. There were seven persons in the party; the bride and groom, the bride’s sister, the groom’s brother and sister, a French soldier and myself. I was the only American. As we reached town on returning from the stroll Colonel George McMaster, Commanding Officer of our regiment accosted me and demanded, “Who are you. What are you doing with these people?” I told him and he called a Military Police and ordered me taken to the Adjutant with orders for the Adjutant to prefer charges against me for accompanying white people. On arriving at the Adjutant’s hotel we found Capt. Willis there evidently waiting for me to be brought in. The Adjutant only asked two questions, “Was he with a girl?” “What is your name and to what company do you belong?” Then he said, “Put him in the guard house.”

The following afternoon I was ordered to appear for trial. At 1:15 p.m. I was taken through the streets to the Town Major’s [sic] office by an armed guard who was a private soldier—my rank was not respected. I was called into the room and was surprised to find there was no one present but Major Paul Murry. He read the charges which had me charged with violating the 96th Article of War4 and with disobeying General Order No. 40. After reading the charges he asked for my plea. I told him that I did not care to plea that I would exercise my right as a non-commissioned to refuse trial in a Summary Court.5 This was a complete surprise to him. He had no idea that I was aware of my rights. He looked it up in the Manual of Army Court Martials [sic] and said that it was my right but I was very foolish to use it.6 I told him that from the appearance of things there had been no intention of giving me a fair trial. The prosecuting witness was not present, the members of the board were absent and I had not been given an opportunity to call witness or secure counsel. At first he tried to frighten and intimidate me by saying that if I were given a General Court Martial7 trial I would be left in France awaiting trial after my regiment had gone home. He also said that I might get six months in Leavenworth if I should be found guilty.8 (Can you imagine it—six months for walking on the street with white people.) After he saw he could not intimidate me he assumed the air of comradeship [sic] and used all his presusaive [sic] powers to intice [sic] me to submit to a speedy quiet trial in his kangaroo court9 but I stood pat. He said that I was trying to play martyr and was trying to make a big fuss out of a little incident, but I claimed that I was standing for a principle, that I had been unjustly treated, that the G.O. was unconstitutional, undemocratic and in direct opposition to the principles for which we had fought. I asked that General [John J.] Pershing be given a copy of the General Order and also a copy of the charges against me.10 He laughed at this request and said that the General was too busy for such small matters. He gave me a half an hour to think the matter over and stated that I might get some advice from the officers present. There were only two present. They had come in during the argument. One was Capt. Willis and the other Capt. Benj. Thomas. I took the matter up with Capt. Thomas and in the meantime my Detachment Commander, Major E. B. Simmons (white), of Massachusetts came in and I told him my story. He became indignant and told me to fight it to the last ditch and he would do all in his power to help me. I returned to the court room, and demanded a General Court Martial Trial and a release from the guard house pending trial. Major Murry said that I was making a great mistake and reluctantly gave me a release from the guard house.

That night I visited some of my French friends and found that the whole town was in an uproar over my case. M. Meziere had been to prevail on the Town Mayor in my behalf and was informed that nothing could be done as the Americans had charge of the town. M. Meziere had also called on Brig. Gen. Gehardt our Brigade Commander, another Negro-hater of the meanest type. He refused to even give M. Meziere a civil audience. M. Meziere then went to the Town Mayor and swore to an affidavit that my character was of the best, that I was a respected friend of the family and was their invited guest. Mme. Emil Harmon, my landlady also made an affidavit of character in my behalf (I now have both affidavits in my possession).

The following day I was rearrested at my billet11 and placed in the guard house, contrary to military rules. The Manual of Army Court Martials [sic] states that a non-commissioned officer shall not be confined in a guard house with privates but no attention was paid to that rule.12 No charges were given and no explanation made except that it was Colonel McMaster’s orders. I was released that night and sent to my Detachment under “arrest in quarters.” Nothing more has been said about the case to this day except at New York when I asked Major Murry when I was going to have my trial and he said that the best thing to do was to keep quiet about it.

On March 22, 1919, I was given an honorable discharge from the army, with character grade Excellent and rank of Sergeant M.D. No mention of the case was made on my Service Record. If I had committed an offense sufficient to cause me to be arrested twice and placed in the guard house, why was I given an honorable discharge with an Excellent grade character and a non-commissioned officer’s rank?

If space would permit I could quote other instances where our boys were shamefully mistreated by the white Americans while in France.

Respectfully yours,

Charles R. Isum

Formerly Sergeant Medical Detachment, 365th Inf

- 1. The May 1919 issue of The Crisis contained W. E. B. Du Bois’s “Returning Soldiers” editorial.

- 2. Isum is referencing Headquarters 92nd Division General Orders no. 40, December 26, 1918. The exact wording was: “The especial duties with which the Military Police and Sentinels are charged are . . . (e) To prevent enlisted men from addressing or holding conversation with the women inhabitants of the town.” Available at https:// credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b219-i040.

- 3. In the first part of the twentieth century, “colored” and “Negro” were considered polite terms to use when referencing African Americans, part of an effort to eradicate common usage of the n-word. The legacy of these terms persists in the names of premier civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (founded in 1910) and the United Negro College Fund (founded in 1944). Since the 1960s “Black,” “African American,” and more recently “people of color” have become the preferred terms of usage in American society.

- 4. The 96th Article of War (1917) covered “all conduct of a nature to bring discredit upon the military service.

- 5. A summary court-martial tried charges of minor misconduct and was adjudicated by one officer.

- 6. Isum was referring to the passage in the Manual of Courts Martial, 1917 stating: “Summary courts-martial shall have the power. . . to try any person subject to military law, except . . . a non-commissioned officer who objects” (p. 23).

- 7. A general court-martial was reserved for serious offenses and more closely resembled a civilian court trial with a judge advocate presiding, counsel for the accused, and a panel of officers as jury.

- 8. The military prison at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, housed the Army’s most serious offenders.

- 9. A kangaroo court is a legal proceeding that ignores the law to reach a predetermined verdict.

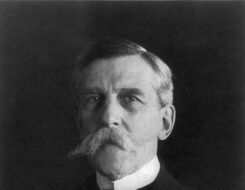

- 10. Pershing (1860–1948) was the commander of the AEF.

- 11. A billet is soldier’s temporary lodging, usually a civilian house.

- 12. The rule states that “non-commissioned officers will not be confined in company with privates if it can be avoided,” Manual of Courts Martial, 1917 (p. 27).

Navigating the North

May 17, 1919

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.