No related resources

Introduction

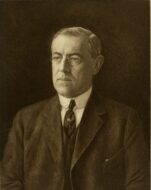

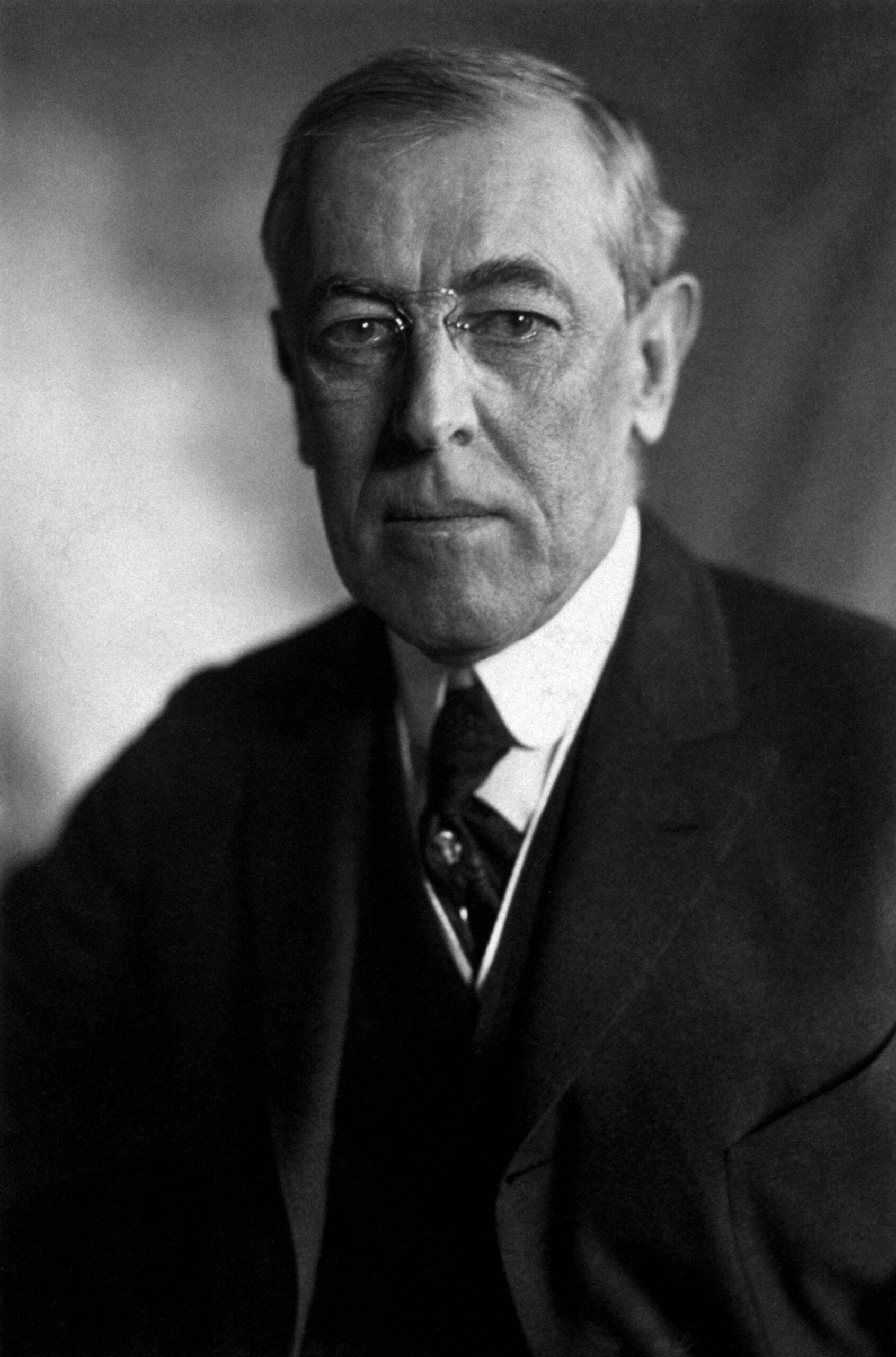

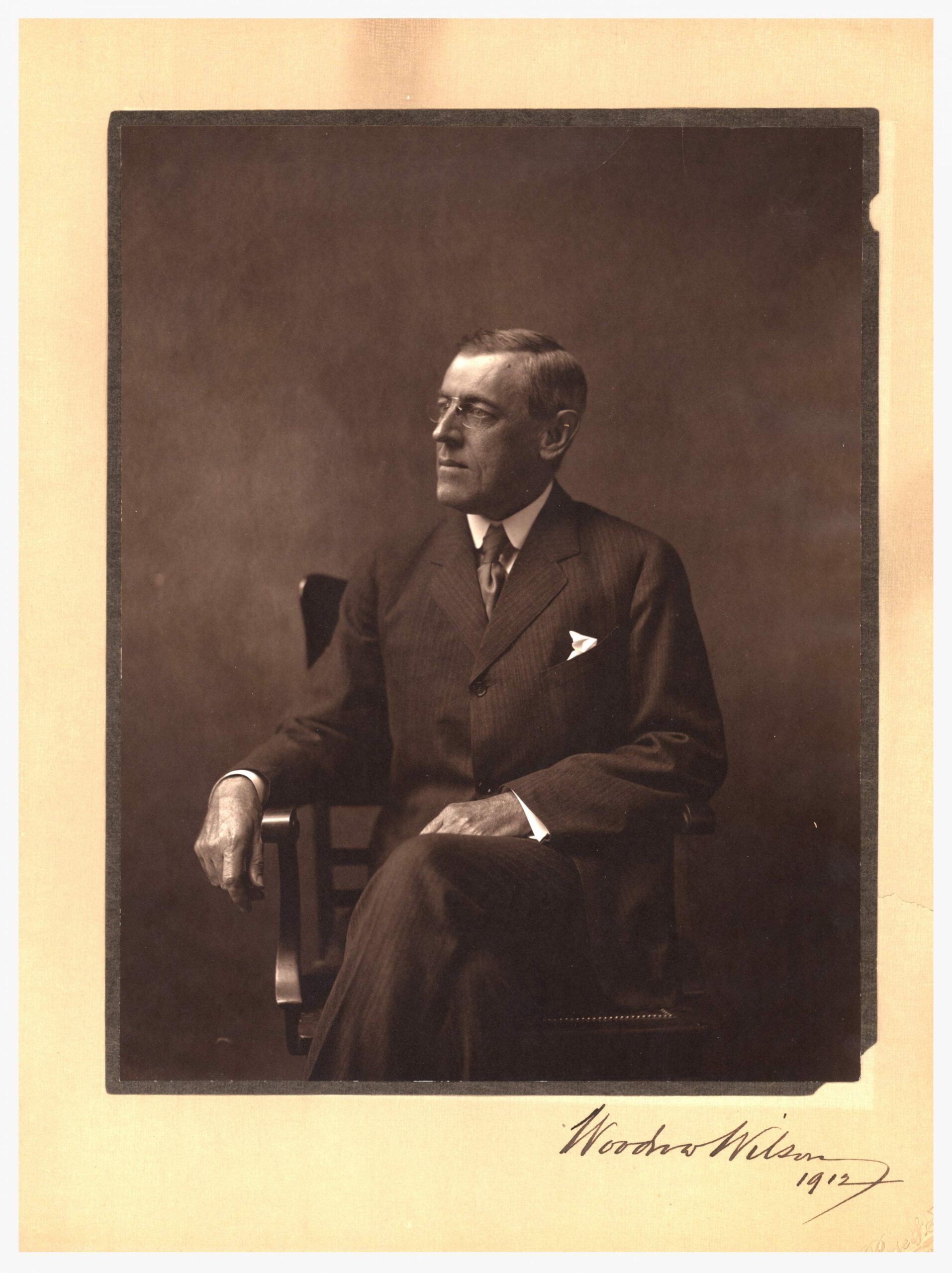

Alice Paul (1885–1977) traveled to Europe in 1909 to study social work. Her life took a different turn when she joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the militant British suffragist organization founded by Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928) in 1903. The WSPU used demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience to bring attention to the cause of female suffrage, and by the time she returned home Paul had already experienced arrest and prison. As a leader in the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), Paul organized the 1913 Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC, on the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s (1856–1924) inauguration to put pressure on the incoming president to support women’s right to vote. Frustrated with NAWSA’s moderate tactics, in 1916 Paul and fellow activist Lucy Burns (1879–1966) founded the National Woman’s Party (NWP) to campaign for a suffrage amendment to the Constitution.

The NWP soon pioneered a new protest tactic—picketing the White House. The “Silent Sentinels” began their vigil in January 1917 holding banners that read: “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty.” City authorities arrested and imprisoned hundreds of suffragists who refused to stop picketing over the course of the year.

On October 20, 1917, Paul was arrested and sentenced to seven months in prison. In Jailed for Freedom, fellow suffragist Doris Stevens chronicled Paul’s ordeal when she began a twenty-two-day hunger strike. Faced with mounting public anger as news of mistreatment leaked out, the Wilson administration secured the release of all suffragist prisoners in late November 1917.

Doris Stevens, “Alice Paul in Prison,” in Jailed for Freedom (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1920), 213–226. Available at https://books.google.com/books?id=R-GGAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA210&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false.

MR. HART (Prosecuting Attorney for the Government): Sergeant Lee, were you on Pennsylvania Avenue near the White House Saturday afternoon?

SERGEANT LEE: I was.

MR. HART: At what time?

LEE: About 4:35 in the afternoon.

HART: Tell the court what you saw.

LEE: A little after half-past four, when the department clerks were all going home out Pennsylvania Avenue, I saw four suffragettes coming down Madison Place, cross the Avenue and continue on Pennsylvania Avenue to the gate of the White House, where they divided two on the right and two on the left side of the gate.

HART: What did you do?

LEE: I made my way through the crowd that was surrounding them and told the ladies they were violating the law by standing at the gates, and wouldn’t they please move on?

HART: Did they move on?

LEE: They did not; and they didn’t answer either.

HART: What did you do then?

LEE: I placed them under arrest.

HART: What did you do then?

LEE: I asked the crowd to move on.

Mr. Hart then arose and summing up said: “Your Honor, these women have said that they will picket again. I ask you to impose the maximum sentence.”

Such confused legal logic was indeed drôle!1

“You ladies seem to feel that we discriminate in making arrests and in sentencing you,” said the judge heavily. “The result is that you force me to take the most drastic means in my power to compel you to obey the law.”

More legal confusion!

“Six months,” said the judge to the first offenders, “and then you will serve one month more,” to the others.

Miss Paul’s parting remark to the reporters who intercepted her on her way from the courtroom to begin her seven months’ sentence was:

“We are being imprisoned, not because we obstructed traffic, but because we pointed out to the president the fact that he was obstructing the cause of democracy at home, while Americans were fighting for it abroad.”

I am going to let Alice Paul tell her own story, as she related it to me one day after her release:

It was late afternoon when we arrived at the jail. There we found the suffragists who had preceded us, locked in cells.

The first thing I remember was the distress of the prisoners about the lack of fresh air. Evening was approaching, every window was closed tight. The air in which we would be obliged to sleep was foul. There were about eighty negro2 and white prisoners crowded together, tier upon tier, frequently two in a cell. I went to a window and tried to open it. Instantly a group of men, prison guards, appeared; picked me up bodily, threw me into a cell and locked the door. Rose Winslow and the others were treated in the same way.3

Determined to preserve our health and that of the other prisoners, we began a concerted fight for fresh air. The windows were about twenty feet distant from the cells, and two sets of iron bars intervened between us and the windows, but we instituted an attack upon them as best we could. Our tin drinking cups, the electric light bulbs, every available article of the meager supply in each cell, including my treasured copy of Browning’s poems which I had secretly taken in with me, was thrown through the windows. By this simultaneous attack from every cell, we succeeded in breaking one window before our supply of tiny weapons was exhausted. The fresh October air came in like an exhilarating gale. The broken window remained untouched throughout the entire stay of this group and all later groups of suffragists. Thus was won what the “regulars” in jail called the first breath of air in their time.

The next day we organized ourselves into a little group for the purpose of rebellion. We determined to make it impossible to keep us in jail. We determined, moreover, that as long as we were there we would keep up an unremitting fight for the rights of political prisoners.4…

However gaily you start out in prison to keep up a rebellious protest, it is nevertheless a terribly difficult thing to do in the face of the constant cold and hunger of undernourishment. Bread and water, and occasional molasses, is not a diet destined to sustain rebellion long. And soon weakness overtook us. At the end of two weeks of solitary confinement, without any exercise, without going outside of our cells, some of the prisoners were released, having finished their terms, but five of us were left serving seven months’ sentences, and two, one month sentences. With our number thus diminished to seven, the authorities felt able to cope with us. The doors were unlocked and we were permitted to take exercise. Rose Winslow fainted as soon as she got into the yard, and was carried back to her cell. I was too weak to move from my bed. Rose and I were taken on stretchers that night to the hospital.

For one brief night we occupied beds in the same ward in the hospital. Here we decided upon the hunger strike, as the ultimate form of protest left us—the strongest weapon left with which to continue within the prison our battle against the Administration. . . .

. . .Commissioner Gardner, with whom I had previously discussed our demand for treatment as political prisoners, made another visit.5 “All these things you say about the prison conditions may be true,” said Mr. Gardner, “I am a new Commissioner, and I do not know. You give an account of a very serious situation in the jail. The jail authorities give exactly the opposite. Now I promise you we will start an investigation at once to see who is right, you or they. If it is found you are right, we shall correct the conditions at once. If you will give up the hunger strike, we will start the investigation at once.”

“Will you consent to treat the suffragists as political prisoners, in accordance with the demands laid before you?” I replied

Commissioner Gardner refused, and I told him that the hunger strike would not be abandoned. But they had by no means exhausted every possible facility for breaking down our resistance. I overheard the Commissioner say to Dr. Gannon on leaving, “Go ahead, take her and [force] feed her.”

I was thereupon put upon a stretcher and carried into the psycopathic [sic] ward.

There were two windows in the room. Dr. Gannon immediately ordered one window nailed from top to bottom. He then ordered the door leading into the hallway taken down and an iron-barred cell door put in its place. He departed with the command to a nurse to “observe her.”

Following this direction, all through the day once every hour, the nurse came to “observe” me. All through the night, once every hour she came in, turned on an electric light sharp in my face, and “observed” me. This ordeal was the most terrible torture, as it prevented my sleeping for more than a few minutes at a time. And if I did finally get to sleep it was only to be shocked immediately into wide-awakeness with the pitiless light. . . .

It is scarcely possible to convey to you one’s reaction to such an atmosphere. Here I was surrounded by people on their way to the insane asylum. Some were waiting for their commitment papers. Others had just gotten them. And all the while everything possible was done to attempt to make me feel that I too was a “mental patient.”. . .

After another week spent by Miss Paul on hunger strike in the hospital, the administration was forced to capitulate. The doors of the jail were suddenly opened, and all suffrage prisoners were released.

With extraordinary swiftness the administration’s almost incredible policy of intimidation had collapsed. Miss Paul had been given the maximum sentence of seven months, and at the end of five weeks the administration was forced to acknowledge defeat. They were in a most unenviable position. If she and her comrades had offended in such degree as to warrant so cruel a sentence (with such base stupidity on their part in administering it), she most certainly deserved to be detained for the full sentence. The truth is, every idea of theirs had been subordinated to the one desire of stopping the picketing agitation. To this end they had exhausted all their weapons of force. . . .

- 1. Drôle is a French word meaning amusing.

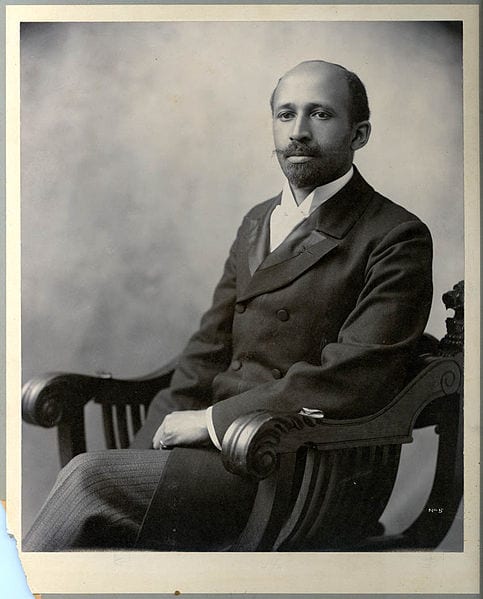

- 2. In the first part of the twentieth century, “colored” and “Negro” were considered polite terms to use when referencing African Americans, part of an effort to eradicate common usage of the n-word. The legacy of these terms persists in the names of premier civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (founded in 1910) and the United Negro College Fund (founded in 1944). Since the 1960s “Black,” “African American,” and more recently “people of color” have become the preferred terms of usage in American society.

- 3. NWP leader Rose Winslow (1889–1977) joined Paul in refusing to work or eat and kept a secret diary detailing their ordeal.

- 4. Burns began the campaign demanding political prisoner status after her imprisonment in September 1917. She had inmates sign a petition that was smuggled out and delivered to the District of Columbia commissioners. In response, prison authorities put the signers in solitary confinement.

- 5. District of Columbia Commissioner William Gwynn Gardner.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.