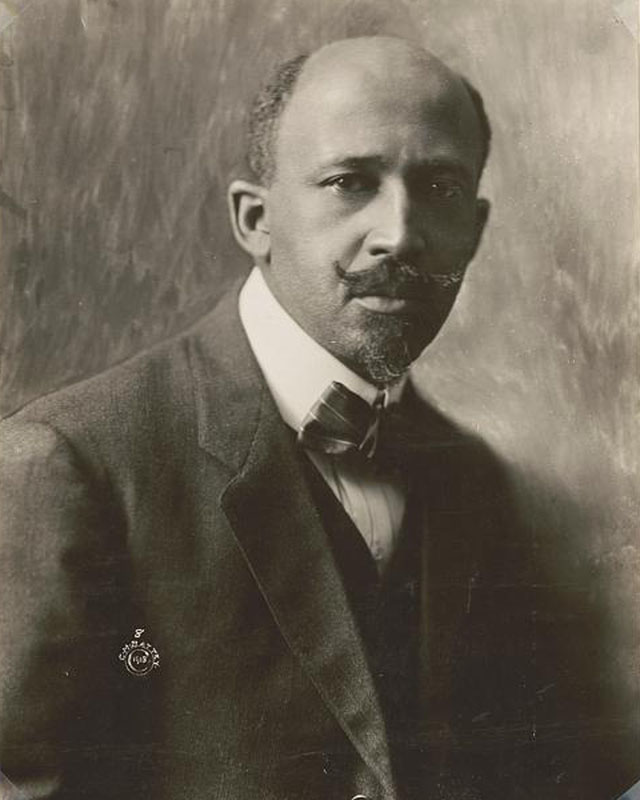

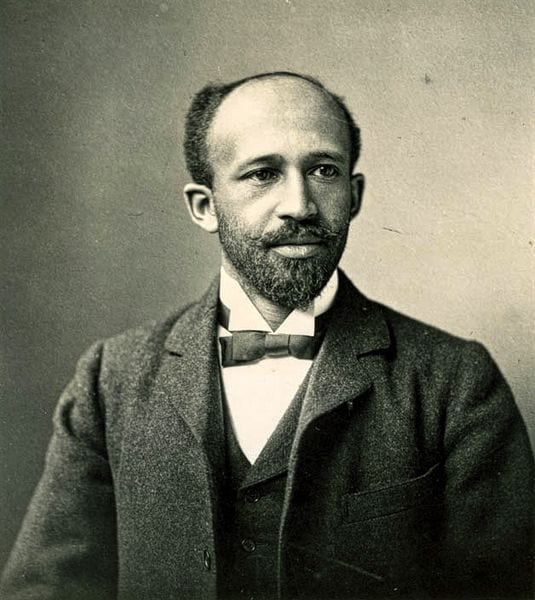

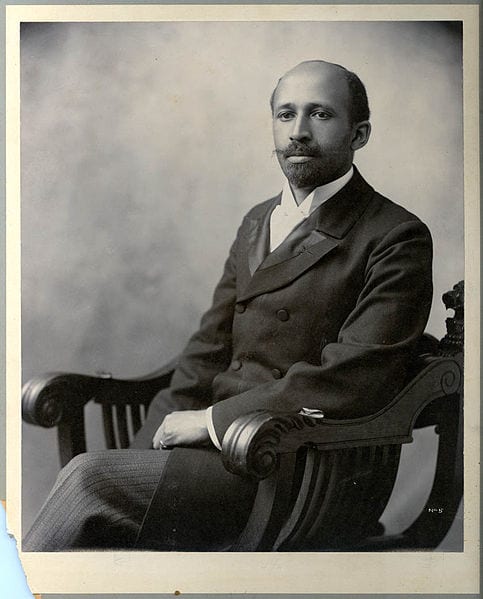

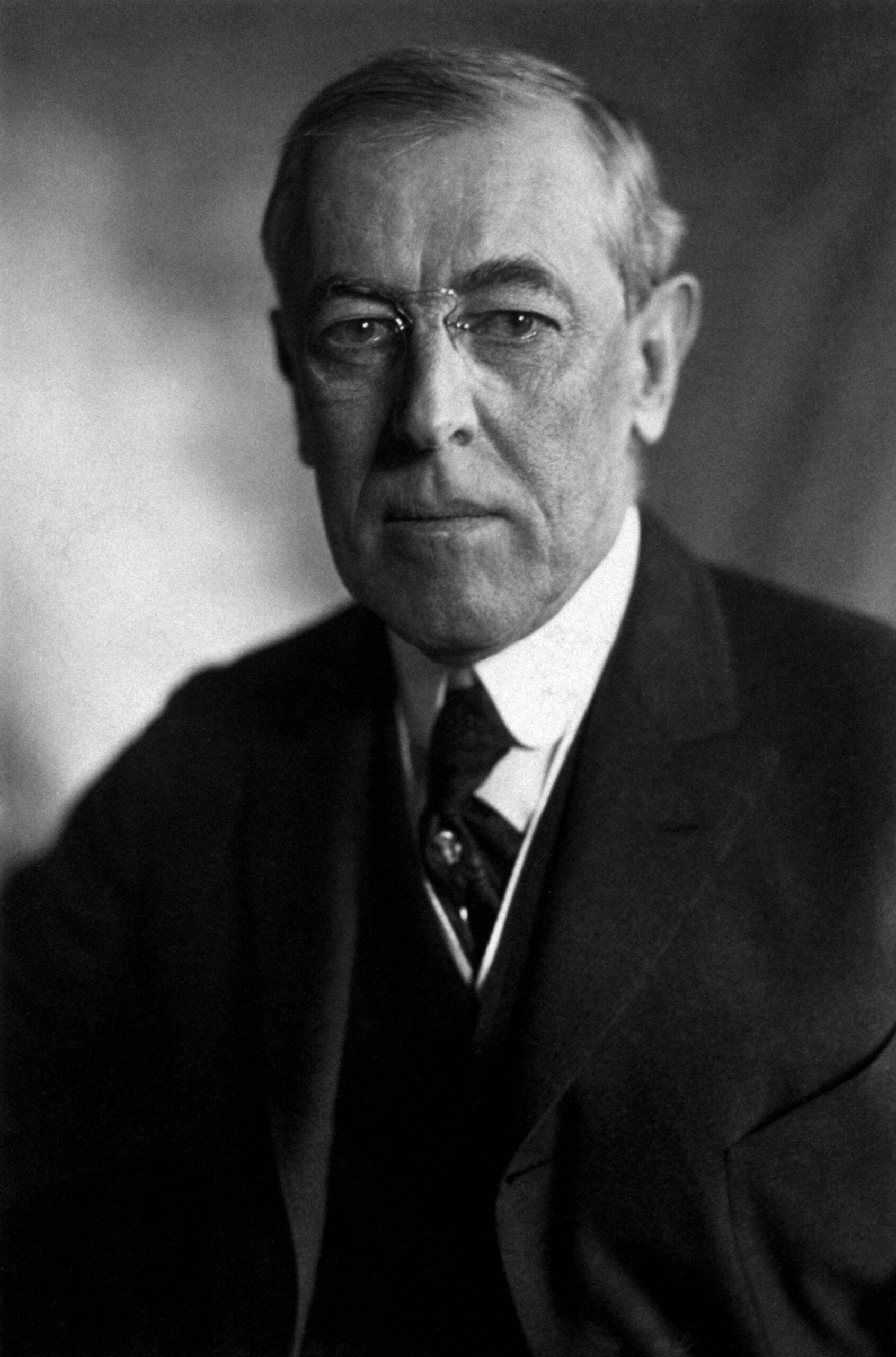

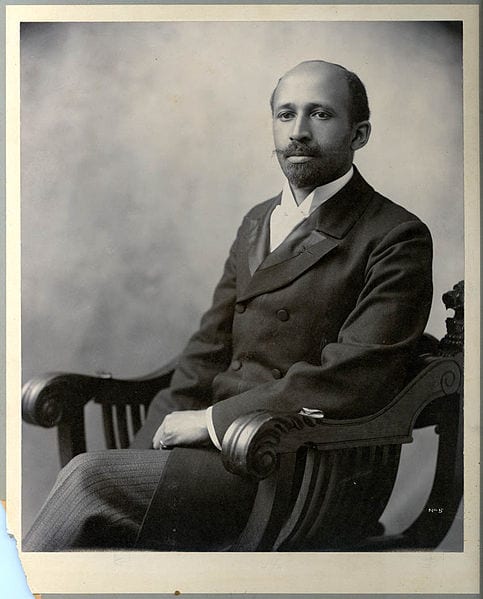

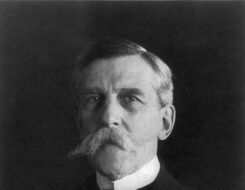

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) was a leading civil rights activist, scholar, and editor of The Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In June 1917 Du Bois declared that “absolute loyalty in arms and in civil duties need not for a moment lead us to abate our just complaints and just demands.” Over the next year, mounting disaffection within the Black community over racial discrimination and violence threatened to hinder the nation’s economic and military mobilization.

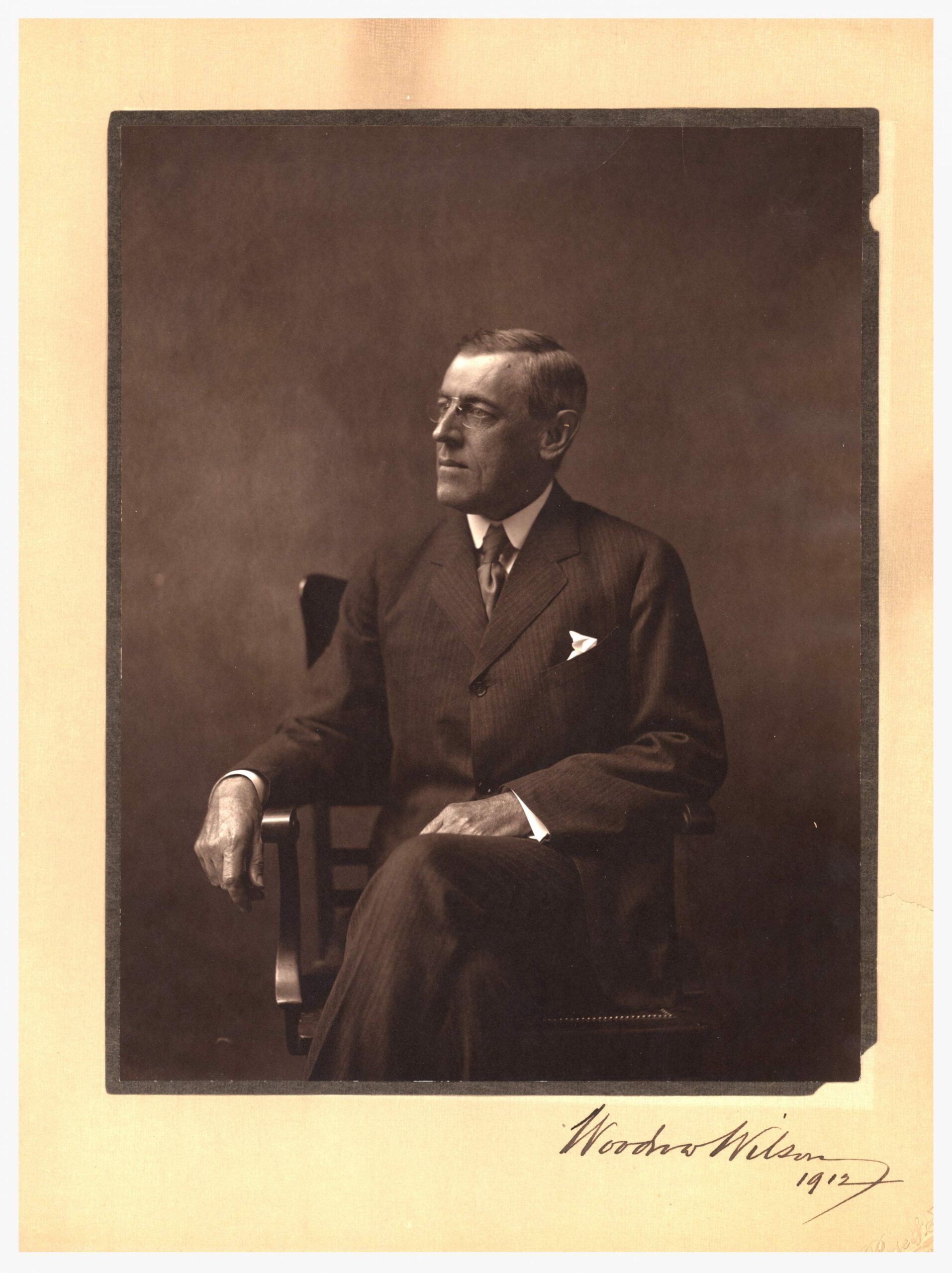

In response, George Creel, the head of the Committee on Public Information, convened a conference of Black newspaper editors to enlist their help in raising African Americans’ morale. Attendees compiled a list of fourteen demands (a nod to Wilson’s Fourteen Points) but also pledged their loyalty. Their demands included a statement from the administration on lynching; more Black men and women appointed to skilled, combatant, and leadership positions in the military; press releases detailing Black soldiers’ heroism; and an end to segregation on trains (the government controlled the railroads during the war). A few weeks later, Du Bois published his “Close Ranks” editorial, shocking many readers with its conciliatory tone. News that Du Bois had applied for an Army captaincy (which he never received) made some wonder if he had struck a side bargain at the conference.

—Jennifer D. Keene