No related resources

Introduction

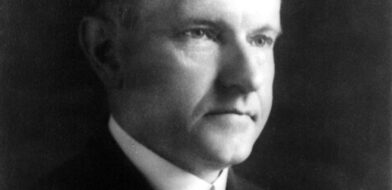

John J. Raskob’s life (1879–1950) was a classic rags-to-riches tale. A self-made businessman and financier who got his start selling candy on railway cars as a teenager, Raskob believed that credit and investment were the keys to economic growth. He convinced General Motors to offer installment plans to help consumers purchase automobiles and later used his own personal fortune to finance the construction of the Empire State Building in New York City.

In 1929 Raskob began crafting plans to draw small, primarily working-class investors into the stock market. In this Ladies’ Home Journal article, Raskob claimed that purchasing shares in a well-managed investment trust offered all Americans a realistic way to accumulate wealth. This advice, made two months before the stock market crashed, proved spectacularly ill-timed. Nonetheless, Raskob accurately anticipated the mutual funds accounts used today by millions of Americans to invest in stocks and bonds.

Samuel Crowther, “Everybody Ought to Be Rich: An Interview with John J. Raskob,” Ladies’ Home Journal (August 1929), 9; 36. Available at https://archive.org/details/sim_ladies-home-journal_1929-08_46_8/page/n9/mode/2up.

Being rich is, of course, a comparative status. A man with a million dollars used to be considered rich, but so many people have at least that much in these days, or are earning incomes in excess of a normal return from a million dollars, that a millionaire does not cause any comment. . . .

It is quite true that wealth is not so evenly distributed as it ought to be and as it can be. And part of the reason for the unequal distribution is the lack of systematic investment and also the lack of even moderately sensible investment.

One class of investors saves money and puts it into savings banks or other mediums that pay only a fixed interest. Such funds are valuable, but they do not lead to wealth. A second class tries to get rich all at once, and buys any wildcat security that comes along with the promise of immense returns. A third class holds that the return from interest is not enough to justify savings, but at the same time has too much sense to buy fake stocks—and so saves nothing at all. Yet all the while wealth has been here for the asking.

The common stocks of this country have in the past ten years increased enormously in value because the business of the country has increased. Ten thousand dollars invested ten years ago in the common stock of General Motors would now be worth more than a million and a half dollars. And General Motors is only one of many first-class industrial corporations.

It may be said that this is a phenomenal increase and that conditions are going to be different in the next ten years. That prophecy may be true, but it is not founded on experience. In my opinion the wealth of the country is bound to increase at a very rapid rate. The rapidity of the rate will be determined by the increase in consumption, and under wise investment plans the consumption will steadily increase.

We Have Scarcely Started

Now anyone may regret that he or she did not have ten thousand dollars ten years ago and did not put it into General Motors or some other good company—and sigh over a lost opportunity. Anyone who firmly believes that the opportunities are all closed and that from now on the country will get worse instead of better is welcome to the opinion—and to whatever increment it will bring. I think that we have scarcely started, and I have thought so for many years.

In conjunction with others I have been interested in creating and directing at least a dozen trusts for investment1 in equity securities. This plan of equity investments is no mere theory with me. The first of these trusts was started in 1907 and the others in the years immediately following. Under all of these the plan provided for the saving of fifteen dollars per month for investment in equity securities2 only. There were no stocks bought on margin,3 no money borrowed, nor any stocks bought for a quick turn or resale. All stocks with few exceptions have been bought and held as permanent investments. The fifteen dollars was saved every month and the dividends from the stocks purchased were kept in the trust and reinvested. Three of these trusts are now twenty years old. Fifteen dollars per month equals one hundred and eighty dollars a year. In twenty years, therefore, the total savings amounted to thirty-six hundred dollars. Each of these three trusts is now worth well in excess of eighty thousand dollars. Invested at 6 percent interest, this eighty thousand dollars would give the trust beneficiary an annual income of four hundred dollars per month, which ordinarily would represent more than the earning power of the beneficiary, because had he been able to earn as much as four hundred dollars per month he could have saved more than fifteen dollars.

Suppose a man marries at the age of twenty-three and begins a regular saving of fifteen dollars a month—and almost anyone who is employed can do that if he tries. If he invests in good common stocks and allows the dividends and rights to accumulate, he will at the end of twenty years have at least eighty thousand dollars and an income from investments of around four hundred dollars a month. He will be rich.4 And because anyone can do that I am firm in my belief that anyone not only can be rich but ought to be rich.

The obstacles to being rich are two: The trouble of saving, and the trouble of finding a medium for investment. . . .

Recently I have been advocating the formation of an equity securities corporation; that is, a corporation that will invest in common stocks only under proper and careful supervision. This company will buy the common stocks of first-class industrial corporations and issue its own stock certificates against them. This stock will be offered from time to time at a price to correspond exactly with the value of the assets of the corporation and all profit will go to the stockholders. The directors will be men of outstanding character, reputation and integrity. At regular intervals—say quarterly—the whole financial record of the corporation will be published together with all of its holdings and the cost thereof. The corporation will be owned by the public and with every transaction public. I am not at all interested in a private investment trust. The company would not be permitted to borrow money or go into any debt.

In addition to this company, there should be organized a discount company on the same lines as the finance companies of the motor concerns to be used to sell stock of the investing corporation on the installment plan.5 If Tom had two hundred dollars, this discount company would lend him three hundred dollars and thus enable him to buy five hundred dollars of the equity securities investment company stock, and Tom could arrange to pay off his loan just as he pays off his motor-car loan. When finished he would own outright five hundred dollars of equity stock. That would take his savings out of the free-will class and put them into the compulsory-payment class and his savings would no longer be fair game for relatives, for swindlers or for himself.

People pay for their motor-car loans. They will also pay their loans contracted to secure their share in the nation’s business. And in the kind of company suggested every increase in value and every right would go to the benefit of the stockholders and be reflected in the price and earning power of their stock. They would share absolutely in the nation’s prosperity.

Constructive Saving

The effect of all this would, to my mind, be very far-reaching. If Tom bought five hundred dollars’ worth of stock he would be helping some manufacturer to buy a new lathe6 or a new machine of some kind, which would add to the wealth of the country, and Tom, by participating in the profits of this machine, would be in a position to buy more goods and cause a demand for more machines. Prosperity is in the nature of an endless chain, and we can break it only by our own refusal to see what it is.

Everyone ought to be rich, but it is out of the question to make people rich in spite of themselves.

The millennium is not at hand. One cannot have all play and no work. But it has been sufficiently demonstrated that many of the old and supposedly conservative maxims are as untrue as the radical notions. We can appraise things as they are.

Everyone by this time ought to know that nothing can be gained by stopping the progress of the world and dividing up everything—there would not be enough to divide, in the first place, and, in the second place, most of the world’s wealth is not in such form it can be divided.

The socialistic theory of division is, however, no more irrational than some of the more hidebound theories of thrift or of getting rich by saving.

No one can become rich merely by saving. Putting aside a sum each week or month in a sock at no interest, or in a savings bank at ordinary interest, will not provide enough for old age unless life in the meantime be rigorously skimped down to the level of mere existence. And if everyone skimped in any such fashion then the country would be so poor that living at all would hardly be worthwhile.

Unless we have consumption we shall not have production. Production and consumption go together, and a rigid national program of saving would, if carried beyond a point, make for general poverty, for there would be no consumption to call new wealth into being.

Therefore, savings must be looked at not as a present deprivation in order to enjoy more in the future, but as a constructive method of increasing not only one’s future but also one’s present income. . . .

It is difficult to see why a bond or mortgage should be considered as a more conservative investment than a good stock, for the only difference in practice is that the bond can never be worth more than its face value or return more than the interest, while a stock can be worth more than was paid for it and can return a limitless profit.7

One may lose on either a bond or a stock. If a company fails it will usually be reorganized and in that case the bonds will have to give way to new money and possibly they will be scaled down. The common stockholders may lose all, or again they may get another kind of stock which may or may not eventually have a value. In a failure, neither the bondholders nor the stockholders will find any great cause for happiness—but there are very few failures among the larger corporations.

Beneficial Borrowing

. . .The line between investment and speculation is a very hazy one, and a definition is not to be found in the legal form of a security or in limiting the possible return on the money. The difference is rather in the approach.

Placing a bet is very different from placing one’s money with a corporation which has thoroughly demonstrated that it can normally earn profits and has a reasonable expectation of earning greater profits. That may be called speculation, but it would be more accurate to think of the operation as going into business with men who have demonstrated that they know how to do business.

The old view of debt was quite as illogical as the old view of investment. It was beyond the conception of anyone that debt could be constructive. Every old saw about debt—and there must be a thousand of them—is bound up with borrowing instead of earning. We now know that borrowing may be a method of earning and beneficial to everyone concerned. Suppose a man needs a certain amount of money in order to buy a set of tools or anything else which will increase his income. He can take one of two courses. He can save the money and in the course of time buy his tools, or he can, if the proper facilities are provided, borrow the money at a reasonable rate of interest, buy the tools, and immediately so increase his income that he can pay off his debt and own the tools within half the time that it would have taken him to save the money and pay cash. That loan enables him at once to create more wealth than before and consequently makes him a more valuable citizen. By increasing his power to produce he also increases his power to consume, and therefore he increases the power of others to produce in order to fill his new needs and naturally increases their power to consume, and so on and on. By borrowing the money instead of saving it he increases his ability to save and steps up prosperity at once.

The Way to Wealth

That is exactly what the automobile has done to the prosperity of the country through the plan of installment payments. The installment plan of paying for automobiles, when it was first launched, ran counter to the old notions of debt. It was opposed by bankers, who saw in it only an incentive for extravagance. It was opposed by manufacturers because they thought people would be led to buy automobiles instead of their products.

The results have been exactly opposite to the prediction. The ability to buy automobiles on credit gave an immediate step-up to their purchase. Manufacturing them, servicing them, building roads for them to run on, and caring for the people who used the roads have brought into existence about ten billion dollars of new wealth each year—which is roughly about the value of the farm crops. The creation of this new wealth gave a large increase to consumption and has brought on our present very solid prosperity.

But without the facility for going into debt or the facility for the consumer’s getting credit—call it what you will—this great addition to wealth might never have taken place and certainly not for many years to come. Debt may be a burden, but it is more likely to be an incentive.

The great wealth of this country has been gained by the forces of production and consumption pushing each other for supremacy. The personal fortunes of this country have been made not by saving but by producing.

Mere saving is closely akin to the socialist policy of dividing and likewise runs up against the same objection that there is not enough around to save. The savings that count cannot be static. They must be going into the production of wealth. They may go in as debt and the managers of the wealth-making enterprises take all the profit over and above the interest paid. That has been the course recommended for saving and for the reasons that have been set out—the fallacy of conservative investment which is not conservative at all.

The way to wealth is to get into the profit end of wealth production in this country.

- 1. A trust investment fund holds and manages assets on behalf of others, pooling money from investors to create a diversified portfolio of investments, and distributes profits back to investors.

- 2. Equity securities are stocks or bonds that represent shares, or ownership, in a corporation.

- 3. Buying on margin refers to the prevalent practice in the 1920s of using short-term loans to purchase stocks, with the expectation of quickly reselling those stocks at a higher price to cover the loans and make a profit. The resulting influx of money into the stock market overinflated stock values, creating a bubble that burst in October 1929.

- 4. $400 dollars in 1929 is the equivalent in purchasing power to $7,000 in 2023.

- 5. Installment purchasing plans, which proliferated in the 1920s, allow consumers to buy expensive items by making a small down payment, and then paying off the balance gradually with smaller, regularly scheduled payments that sometimes include interest fees.

- 6. A lathe is a machine tool primarily used to cut or shape wood and metal.

- 7. A bond purchase is a form of loaning money to a company or the government for a set amount of interest. By contrast, a stock purchase makes investors partial owners of a company, and the stock’s value on the stock market determines whether an investor gains or loses money on the investment.

Annual Message to Congress (1929)

December 03, 1929

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.