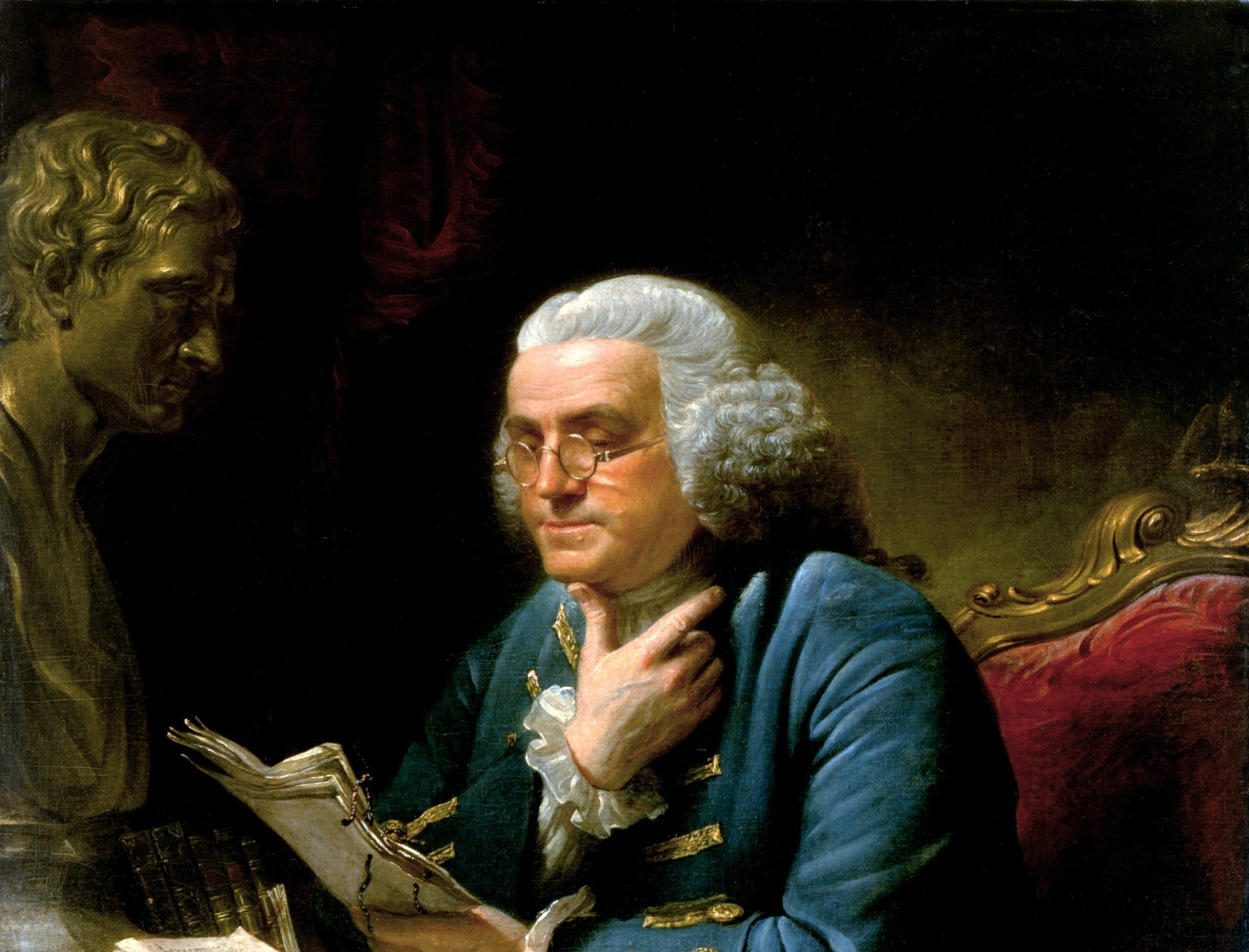

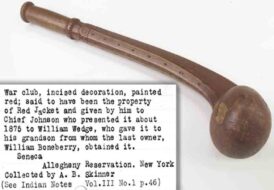

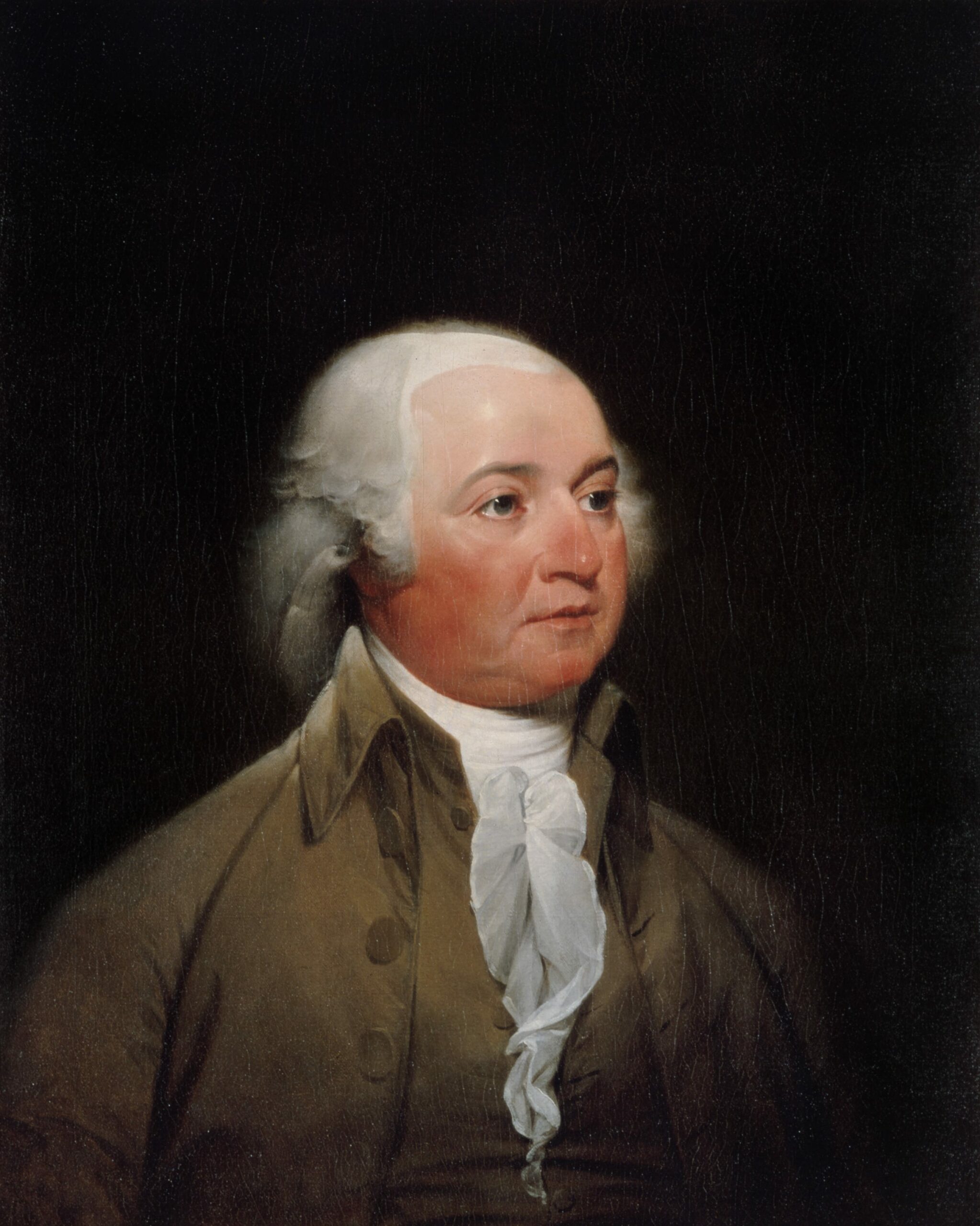

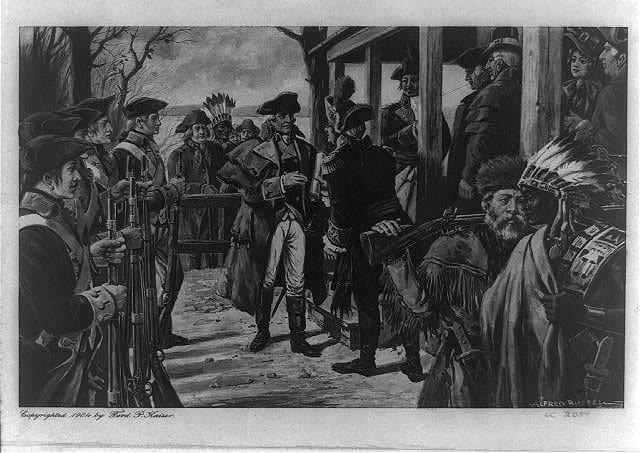

With all due respect to Parson Weems (1759–1825), George Washington’s first biographer, the president did know how to tell a lie, and he was ruthless in his pursuit of intelligence, urging his agents to “leave no stone unturned” in their operations against the British. General Washington’s successful use of intelligence and deception during the Revolutionary War led President Washington to conclude that the new executive office needed a fund at its disposal to handle the “business of intelligence,” as John Jay referred to it. Washington believed intelligence operations were the exclusive province of the executive, a hard-earned lesson taken from the inability of the Continental Congress to protect secrets.

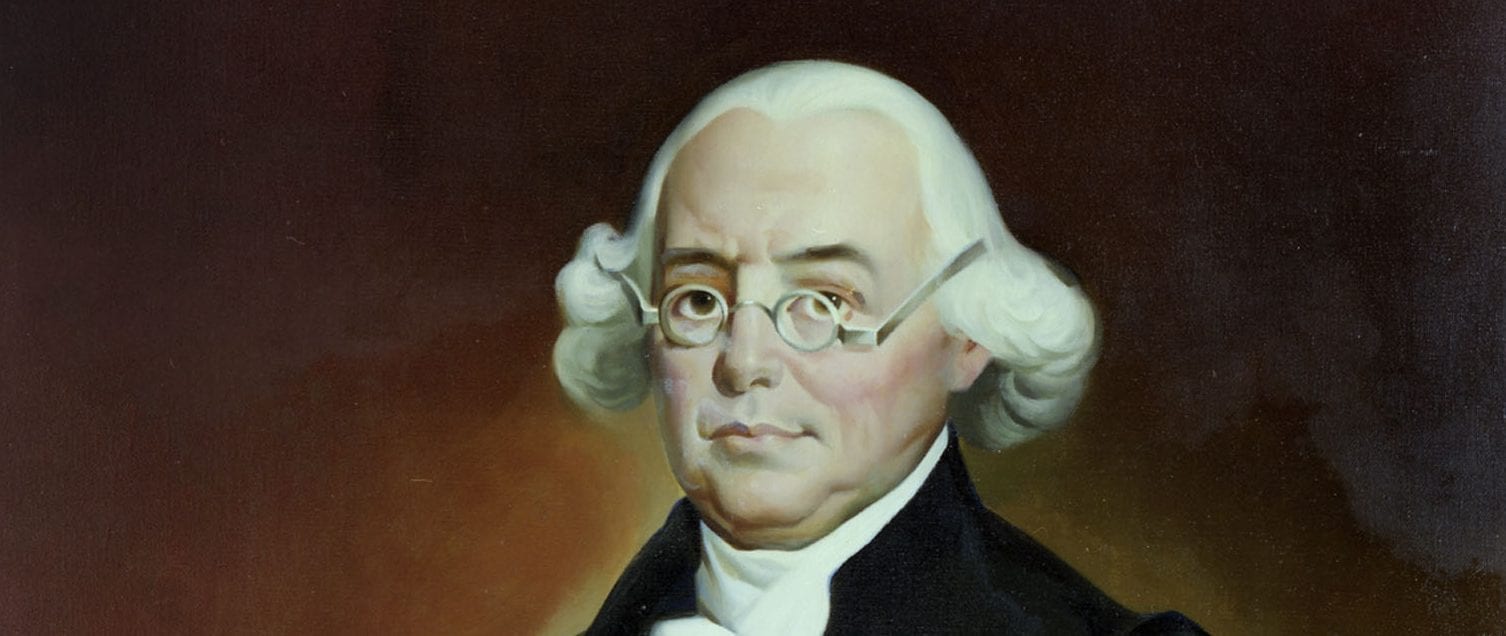

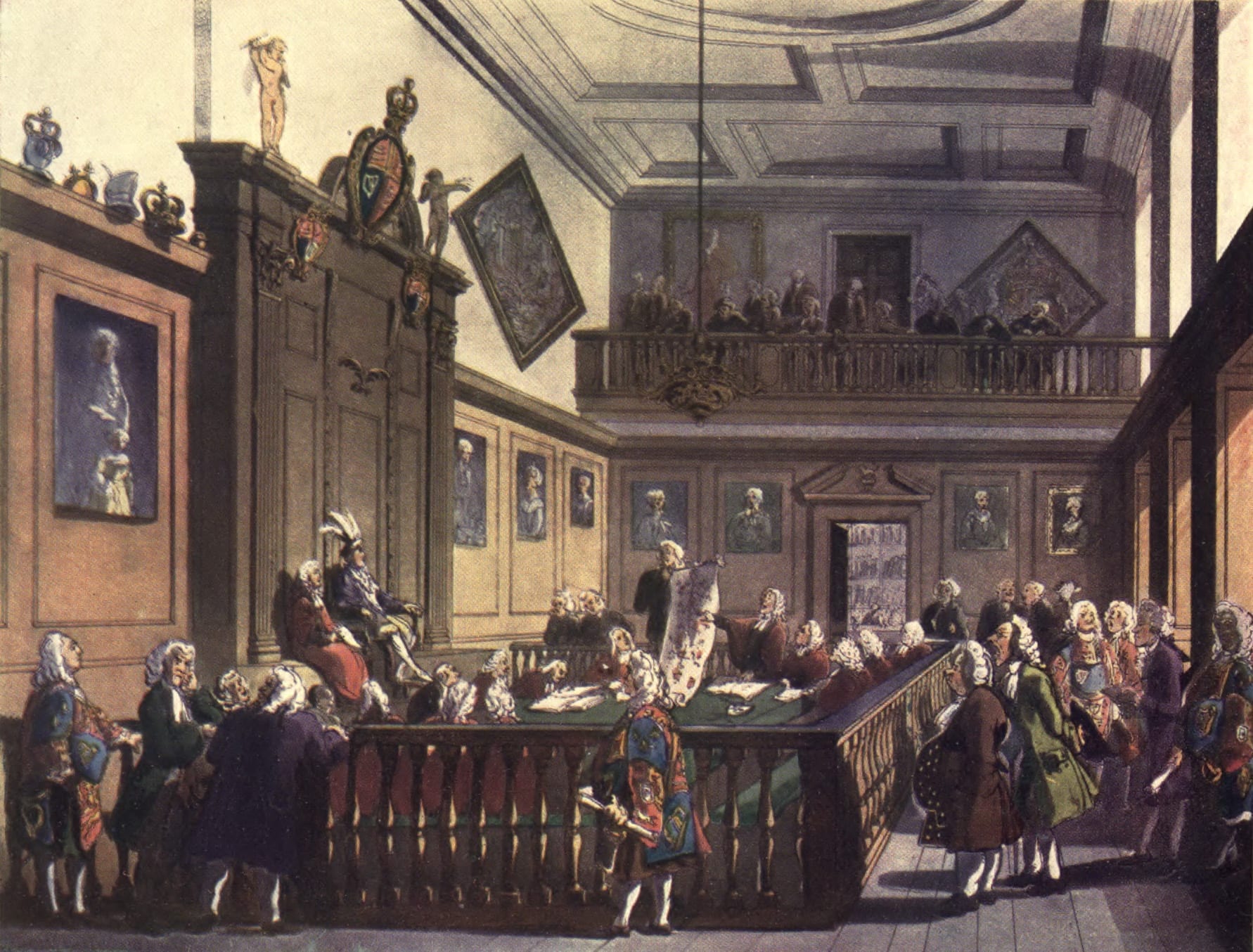

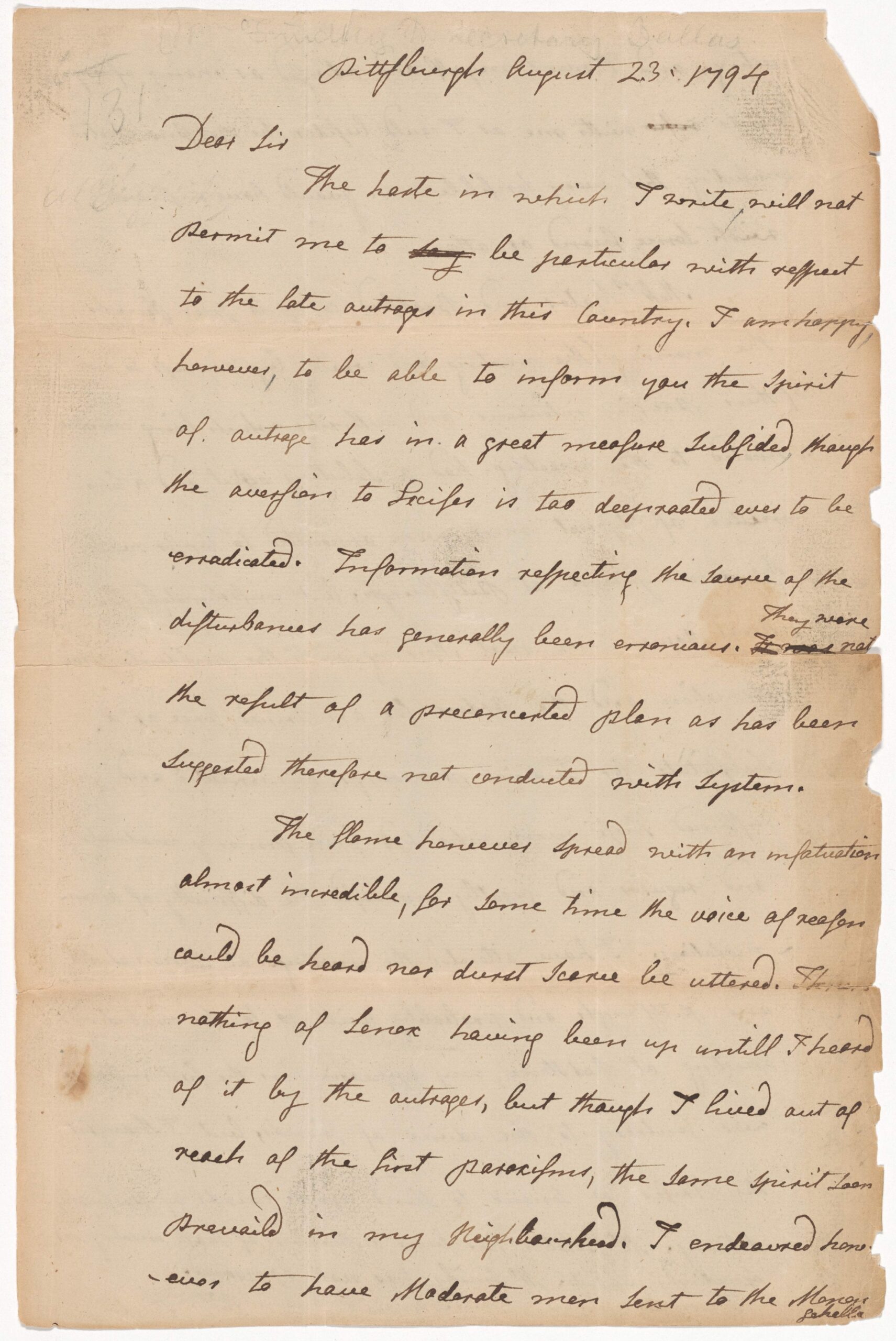

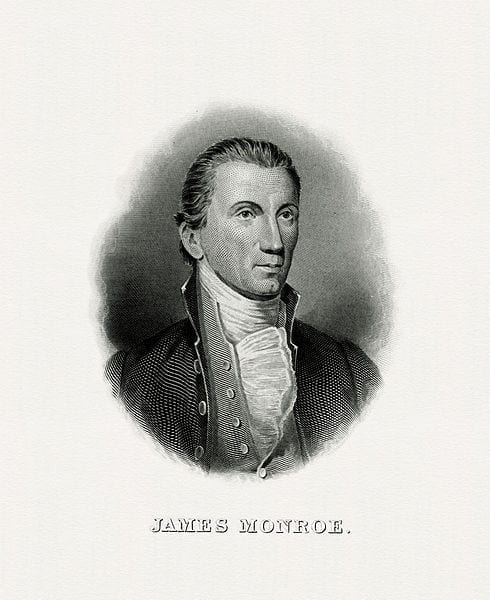

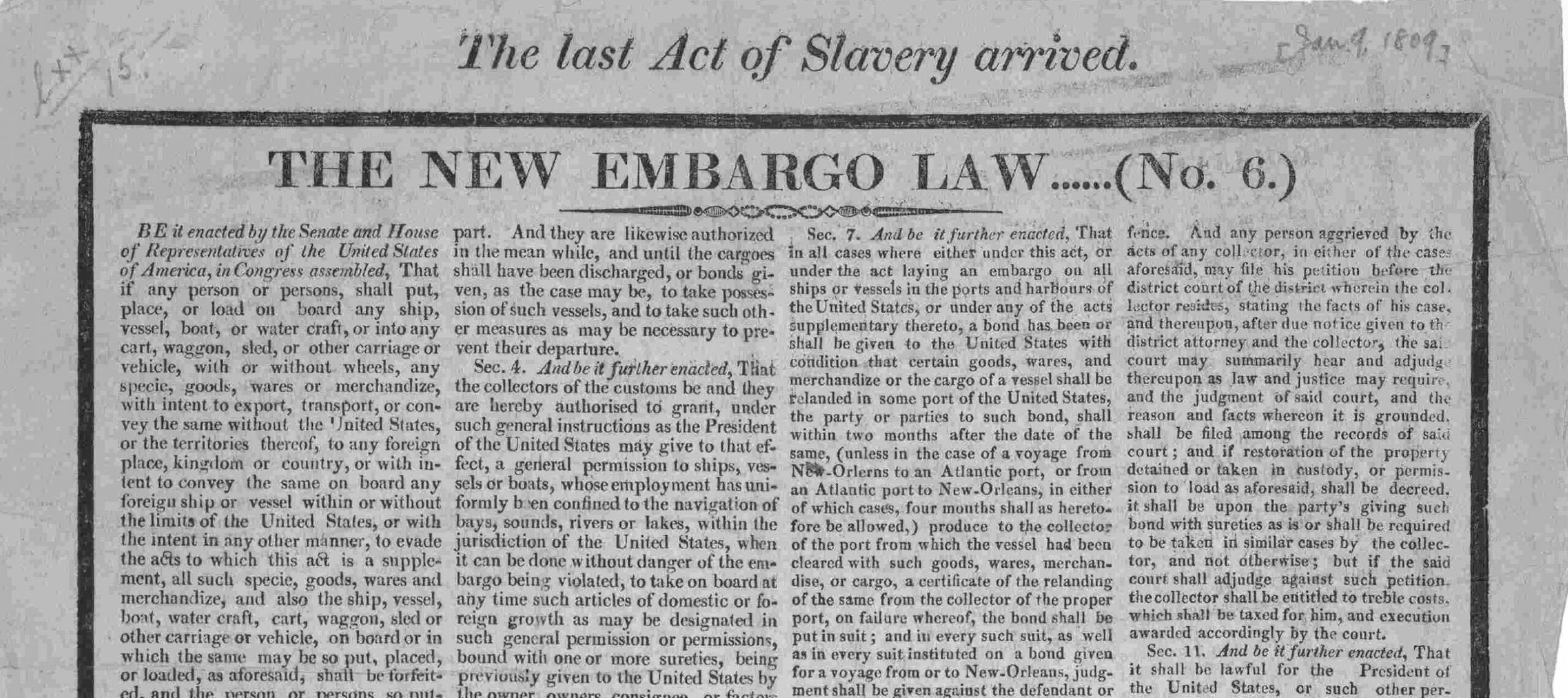

In his First Annual Message to Congress, Washington requested a contingency fund, or as some members of Congress preferred to call it, a “Secret Service” Fund. The fund would be controlled by the president and would allow the chief executive to authorize foreign policy missions free from congressional oversight. The president’s request was approved by Congress in 1790, with the support of Representative James Madison, and with it Washington was granted the authority to avoid the usual reporting procedures mandated by Congress. The president was in essence given a blank check to conduct secret operations that he alone deemed to be in the national interest.

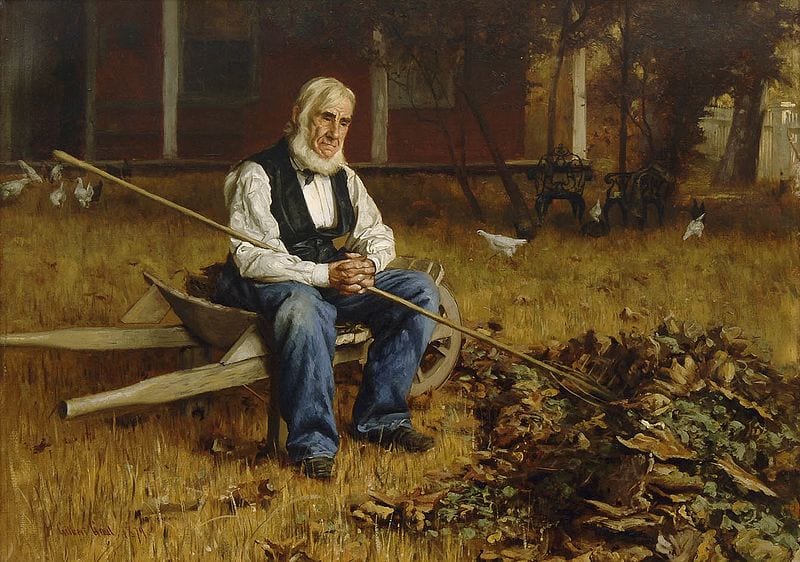

—Stephen F. Knott