No related resources

Introduction

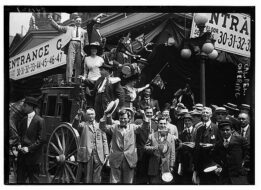

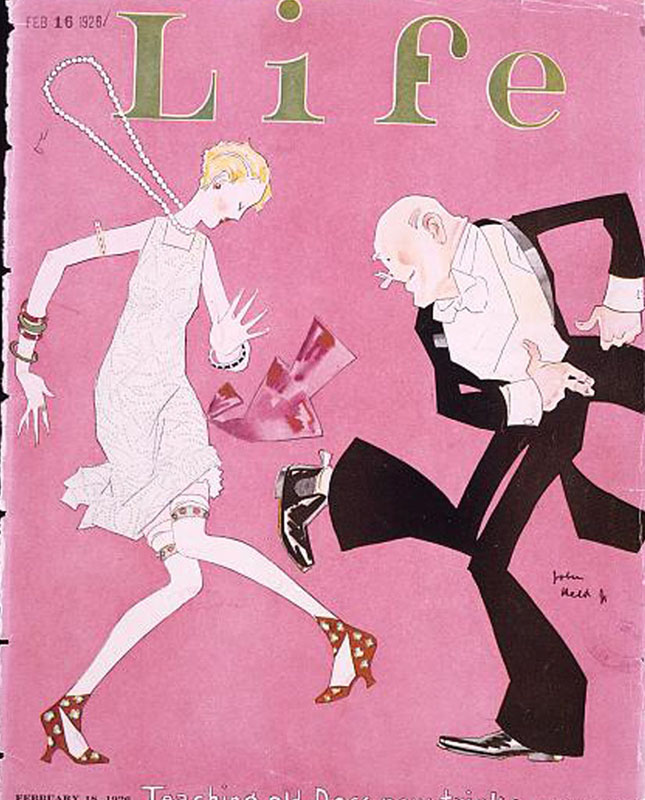

William Oscar Saunders (1884–1940) was a southern journalist who fearlessly denounced lynching, racism, anti-Semitism, and small-town corruption. Saunders was also an accomplished essayist who commented on American culture with a keen satirical wit. In this essay he took on the much-discussed generation gap of the 1920s. The media popularized the term “flapper” to describe rebellious young women who rejected conventional notions of proper female behavior. “Flapper” was a broad term encompassing any young woman who shortened her skirt, bobbed her hair, danced to jazz music, smoked cigarettes, drank alcohol illegally, embraced her sexuality, or disobeyed her elders. In the excerpts below, Saunders explored how the flapper ethos impacted the dynamics of white middle-class family life.

William Oscar Saunders, “Me and My Flapper Daughters,” American magazine (August 1927), 27; 121. Available at https://hdl.handle.net/2027/iau.31858029197666?urlappend=%3Bseq=203%3Bownerid=118316737-207.

I am the father of two flappers: trim-legged, scantily dressed, bobbed-haired, hipless, corsetless, amazing young female things, full of pep, full of joy, full of jazz. They have been the despair of me for two or three summers; but if they don’t fly off and marry and quit me before I’m a century old, I’m going to know those girls.

I used to think I knew my girls. A lot of foolish parents make that same mistake; but it remained for Elizabeth,1 the elder of the two amazing young persons, to open my eyes and show me up in my ignorance.

For instance, I thought my girls were different from the average run of wild young things. My own childhood was spent in a righteous, church-going, psalm-singing little country town, where young folk were taught “to be seen and not heard,” and where a game of croquet on Sunday afternoons was an abomination in the sight of the Lord.

I assume that I am just an average adult and parent. I was fetched up by a modest mother who wore three petticoats and a floor-sweeping skirt, and by a father who kept on his trousers to bathe his torso, and put on his shirt before bathing the rest of him. I never learned from either parent whether I was male or female, or that there was such a division in the human species.

I came up with some old-fashioned ideas about women and woman’s place in the world. There was nothing frank about the age in which I was brought up. It was not even decent to concede that women were bipeds.2

I have worked hard all my life, and while there was a brief period of romance in my life culminating in marriage to a beautiful and sensible girl, I set out rather matter-of-factly about the business of establishing a family. Like most American Babbitts,3 I have had my nose to the grindstone all my days, and thought I was doing pretty good when I put three square meals on the table, kept the furnace going, and paid my building and loan installments.

I rustled for the food for the pantry, the coal for the cellar, the ice for the ice box; I worked for the tailor, the dressmaker, the butcher, the baker, the electric-light maker, the cinema man and the gas-filling stations. And I thought that was job enough for me. I threw over all the work of keeping house and raising the children to my uncomplaining wife.

I guess it is the way of us males to pay the freight and let our wives haul it. The wives have the harder job; but we don’t think much about that. I didn’t; and I didn’t think much about the children. The girls were their mother’s children, and a mother could understand girls better and train them better than a man, anyway. And so I lived on in the same house with two growing-up flapper daughters, and never began to know them until that elder one, Elizabeth, gave me a jolt that “flappergasted” me and almost paralyzed my wife.

As I said a moment ago, like most fond parents, I had kidded myself with the notion that my girls were different from other people’s girls. I had seen other parents’ girls smoking cigarettes, “necking”4 in automobiles on the highways, wearing rolled stockings, or shamelessly promenading on Main Street without stockings at all. . . .

I was sure my girls had never experimented with a hip-pocket flask,5 flirted with other women’s husbands, or smoked cigarettes. My wife entertained the same smug delusion, and was saying something like that out loud at the dinner table one day. And then she began to talk about other girls.

“They tell me that that Purvis girl has cigarette parties at her home,” remarked my wife.

She was saying that for the benefit of Elizabeth, who runs somewhat with the Purvis girl. Elizabeth was regarding her mother with curious eyes. She made no reply to her mother, but turning to me, right there at the table, she said:

“Dad, let’s see your cigarettes.”

Without the slightest suspicion of what was forthcoming, I threw Elizabeth my cigarettes. She withdrew a fag6 from the package, tapped it on the back of her left hand, inserted it between her lips, reached over and took my lighted cigarette from my mouth, lit her own cigarette and blew airy rings toward the ceiling.

My wife nearly fell out of her chair, and I might have fallen out of mine if I hadn’t been momentarily stunned.

“Smoking is no longer a novelty with girls, Mother,” said Elizabeth. “I have been smoking for two years, myself. That’s one thing I learned at college.”

There was a long and tense pause until my wife broke the silence.

“Elizabeth!” she exclaimed. And that was all. For once my wife was inarticulate. . . .

For once in my life, I exercised good judgment, swallowed my hypocritical indignation, and simply said, “I am shocked and surprised; but I should be the last person in the world to lecture you on the evils of nicotine or the incongruity of a sweet and dainty little girl befouling her breath, staining her fingers, and distorting her features with a cigarette stuck in her face. I’ve been smoking cigarettes myself ever since I was six years old when I picked up the habit in the hinterland of a one-teacher rural school on the opening day.”

Elizabeth arched her eyebrows, lifted her chin, and beamed a smile of approval upon me. I think it was the first spontaneous smile of approval I ever had from her. That was the beginning of an understanding between us, and an exchange of confidences that has emboldened me to assert that I expect some day to know my daughters.

We left the dinner table and I followed Elizabeth out on the front porch. I proposed taking a ride, and we climbed into my roadster and took a spin in the country. Out on a country road I offered her another cigarette, to see what she would do.

“Really, I don’t care for it, Dad,” she said. “I didn’t smoke that one at dinner because I especially cared for it; but no self-respecting girl wants to be a hypocrite all of her life, even to spare the feelings of the best mother in the world, who clings to the old-fashioned ideas of things.”

“I knew that you and Mother didn’t believe that I had ever smoked, and it struck me all of a sudden that there was an opportunity to confess, even though it might shock you.”

“I guess you smoke merely because you think it is smart, and you young folks get something of a kick out of defying the old conventions?” I asked.

“Maybe some of us do think it is smart,” replied Elizabeth; “and I think most of us do get a kick in defying your conventions. I saw a book in your library the other day called The Warfare between Science and Christianity. That gave me an idea; I think there is a greater warfare today between young folks and old folks. Old folks say they just can’t understand us young folks; their trouble is, we young folks do understand old folks, and the old folks don’t give us credit for the discernment we have.”

That was the beginning of a series of friendly interviews with my daughter, in which I have learned much in the past few months. Out of the peculiar combination of sophistication and innocence of this typical young female I have acquired something of an understanding of what young folks think of old folks; I have discovered that modern youth is thinking for itself.

If I understand that daughter of mine, the young folks of this generation have very little faith in, or respect for their elders, because they think we elders are unsophisticated, unfair, and insincere. They charge us with unfairness and insincerity because we condemn in them frivolous practices and habits that were common to us when we were young.

“I can imagine Mother having been a very shy and perfectly proper little girl when she was a child,” confides my daughter, “because Mother was brought up in those stay-at-home days of a quarter-century ago, when they didn’t have telephones, radio, movies, automobiles or any place to go except Wednesday-night prayer meetings, Friday-night spelling bees, and Sunday church services. A fifteen-year-old girl of today has seen more of life and has a better understanding of life than her mother had at twenty-five years of age.

“But I think if I had lived in Mother’s day I could have found as much about young folks to criticize as the old folks find to criticize about us. You and Mother didn’t have an automobile to ride around in, and you couldn’t get as far away from home in a ride as we can get today; but you did ride a buggy with a narrow seat in which both of you could barely squeeze and in which your legs were all mixed up in a narrow boxlike space.

“A young man driving an automobile today has to keep at least one hand on the steering wheel; in those days, he threw the reins of the horse loosely over the dash board of the old buggy and had both arms free. And I have an idea he made the most of his freedom.”. . .

I have learned from both daughters. I have learned much from Billie,7 the younger. Bill is eighteen years old and not so articulate as Elizabeth is, nor so bold. Bill is slow to say outright just what she thinks; but she contrives at time to get her viewpoint over to me. . . .

Bill doesn’t smoke. “I would smoke if I liked it,” she says frankly. “But I can’t see any good it does. It makes your teeth bad, hurts your eyes, gives you a cough, and I don’t think it makes anybody think any more of you. Sister sometimes smokes, because Sister thinks it’s smart.”

“I don’t think any such thing,” Elizabeth replied with indignation. “If smoking is bad for girls, it’s bad for men, and when any man wants me to quit smoking I shall expect him to set the example.”

All of which, I think, is our key to the rebellious spirit of modern youth. They are up in arms against the inconsistency of parents and seniors generally.

They have set us down as a lot of moral frauds and hypocrites who do not present the facts of life fairly and squarely to them, and they are determined to explore life for themselves. In their automobiles and in the open-air life that they lead, they see everything in the world and in nature that we have so foolishly tried to keep them from seeing.

Moving pictures bring to them every aspect of human society, at its worst as well as its best. The news-stands are loaded with cheap and trashy magazines in which these young people find frank discussions of phases of life in which they are by nature intensely interested, and about which we older folks maintain a prudish silence in their presence.

I recall now with pain and with a sense of deepest shame my sorry conduct on an occasion when Elizabeth was hardly six years old. She rushed into the house one day all breathless with eager curiosity.

“Where did you get me from, Mother?” she asked with sparkling eyes.

“God made you,” replied her mother.

The answer did not satisfy Elizabeth. She looked long and hard at her mother as if she expected more enlightenment. Presently she turned her curious gaze upon me, as much as to say that surely there was something more to be said, and I would say it.

But I had no word for her. I appeared to be interested in something to read, and tried not to look at her. The little child tiptoed over to me and stood by my chair until I was compelled to notice her. My eyes met hers, her eyes so bright, so clean, so honest, so unafraid.

“Daddy,” she said, “Daddy, who made God?”

I told her I did not know. A perturbed look came over her innocent face, and she went thoughtfully back to her play.

In the very beginning of the awakening of the wonderful mind of the child, she had come to her parents for enlightenment upon two of the greatest mysteries of life, and we had failed her.

Never again did she ask either of us any question touching upon the mystery of life. She knew or surmised that we either did not know or would not tell. In either case, we had put ourselves in a despicable light, and lost that first and surest opportunity to establish an intimacy that would have impressed her profoundly and made us her confidants for life.

These young people are thinking a lot about sex. . . .

For thousands of years, human society has proceeded on the basis of a double standard of morals. Men were permitted to do almost everything that a woman was prohibited from doing. Women have always ruled the world; but they have done it by dissembling, by coquetry, by deceit, by trickery, by playing upon the vanity, the egotism, and the other weaknesses of the male.

The modern girl resents this. She is conscious of her powers and of her place in the world. The conditions that made her mother a slave to the home, even so late as a quarter of a century ago, have vanished and woman has found interesting work outside of the home.

In many instances, the girl takes a man’s place in the world, does a man’s work, and is the breadwinner in fact for a family once slavishly dependent upon the labor of a perhaps indifferent male.

The modern girl does not feel a cringing dependence upon any male under the sun. Her objective is a home, husband, children. She is, first of all, a female, just like her mother, with all the romanticism, all the love-longings, and all the maternal instinct, hopes, and aspirations of motherhood. But she is not going to be satisfied with any sort of man, and she is going to know him before she marries him. . . .

My daughters know that they know more than I knew at their age, and they rightly suspect that they know much today that I do not know. They see more of life in a day than I saw in a month of Sundays when I was a kid. They think nothing of getting over more ground in half a night than I ever covered in a year when I was a boy. My mode of transportation was a horse cart, theirs is a rubber-tired whirlwind.

We didn’t have a telephone in all the town where I spent my boyhood; my youngsters have not only a telephone, but a radio that tunes in with all the world.

I was plodding through grammar school at age sixteen and considered a bright pupil; a girl sixteen years old who isn’t finishing high school today is behind others of her age.

And so these amazing young folks with their superior educational advantages and a wealth of knowledge that was denied their parents, look down upon us older folks as a lot of old fogies. And having discovered much insincerity, much inconsistency and much hypocrisy in us as well, they flaunt our authority. They haven’t given thought yet to the fact that some day they, too, will be old fogies in the eyes of a newer and even wiser generation.

But Elizabeth, like all her type, misses one of the biggest facts of all: the fact that, after all, children owe something to their parents. A parent may be an ignorant and deceitful old fogy, but, after all, he is a parent struggling under the great economic and social burden of rearing dependent offspring. He must provide clothes, food, shelter, education, and certain social, spiritual, and recreational opportunities for his young.

In the great economic struggle to provide these things, he may not have the time to mix with the world and to keep pace with everything new under the sun, as his children do. But in every normal parent’s heart is a great love for and appreciation of his children. His dream is to see them grow up into clean, straight, healthy, happy, dependable men and women.

And if that parent doesn’t know everything that his sophisticated young ones know, he does know one thing very well: he knows that the resources of this frail temple known as the human body must be conserved in youth if one is to be even moderately healthy, happy, and able to enjoy himself in middle life and old age. He grieves to see his children burning up their young lives in tumultuous recreations before they are old enough to recognize, appreciate, and enjoy life’s greatest values.

I hold no brief for us parents. Everything the young folks say about us older folks is just about 100 percent true. But the big economic fact is that we pay the bills; we pay for the food, the clothing, the shelter, the finery of these young folks; the gas they burn and the good times they have. We pay for these things in cash earned by the sweat of our old-fogy brows, and we pay in tearful prayers and sleepless nights for their dissipations and their late hours, regardless of their harmlessness. And because we pay, we think we are entitled to a little more consideration than our children accord us. The only price they are demanded to pay for what they get out of life is parental obedience. I ask these youngsters to answer, in all fairness, if this is not, after all, a moderate price to pay? . . .

But the child has rights which we parents must not ignore. First among these is the right to be heard and understood. When I was a kid, “talking back” to one’s parents was an unpardonable offense. There was no argument; there was but one side to any question involving the child—the parent’s side. The result was an inseparable barrier between parents and children which neither could overcome.

Our irrepressible younger generation is making this less possible today. We can’t help guide our children’s lives unless we really understand them—and real understanding comes only when barriers are gone.

- 1. Saunders’s daughter Elizabeth was twenty-one years old when this essay was composed.

- 2. A biped is an animal that walks on two legs; i.e., a human.

- 3. A reference to the 1922 satirical novel Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis that critiques conformist, status-conscious, white middle-class suburban culture.

- 4. A slang term for kissing and light caressing.

- 5. Hip-pocket flasks became a popular way to carry concealed alcohol during Prohibition.

- 6. A cigarette.

- 7. Census records do not show Saunders as having a second daughter. He did have a son, Keith Saunders.

Annual Message to Congress (1927)

December 06, 1927

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.