No related resources

Introduction

In 1923, the Woman’s Home Companion held a competition inviting readers to submit letters detailing their challenges as homemakers. The following excerpts describe the pressures of child-rearing, managing limited household budgets, economic dependency, marital tensions, and curtailing ambitions. While other women’s magazines proposed buying modern appliances or developing better time-management skills to handle the stress of running a home, the Woman’s Home Companion urged women to organize childcare and housecleaning cooperatives. The editors also encouraged housewives to insist on a more equitable division of labor in the home and to pursue outside interests, including employment.

After the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, feminist activists turned their attention to other forms of gender-based discrimination. The National Woman’s Party, headed by Alice Paul, favored adding an equal rights amendment (ERA) to the Constitution. ERA supporters pointed to state laws that denied married women control of their earnings, the right to hold or inherit property in their own names, or legal custody of their children in the event of divorce. Opponents within the women’s movement worried that an ERA might also eliminate hard-won state laws that protected women, such as maximum hours laws for working mothers. They preferred targeting specific laws for repeal. From 1923 to 1970, the ERA was repeatedly introduced into Congress but never voted upon.

In 1963, forty years after the publication of these letters, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique offered a remarkably similar critique of societal-based gender roles and inequities. Her book helped launch a new phase in the women’s movement known as second wave feminism. The ERA finally made it through Congress in 1972 but was not ratified by the required thirty-eight states before the 1982 deadline.

“My Everyday Problems,” Woman’s Home Companion, vol. 50, no. 7 (July 1923), 25–26; 29. Available at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.319510028031159&view=1up&seq=35.

In the February issue we asked the home women of America who felt themselves to be unreasonably handicapped by the drudgery, the long hours, and the loneliness of housework to write us letters on “My Everyday Problems and Where I Need Help.” In this way we felt that we could arrive more quickly at a knowledge of actual individual problems, and thus, together with our readers, find the way out. More than two thousand letters were received in response to this call. The following were selected for publication because they seem to have covered the ground most thoroughly. “Together” is the solution to this very real and general problem. The Companion’s function is to serve as a clearing-house for the various practical ways in which similar problems have been worked out.

How to Regain the Vision

$50 Prize-Winner

Every woman who begins her married life earnestly and prayerfully has a vision or ideal toward which all of her efforts are directed. As long as she can keep that vision her duties do not seem irksome.

My problems are like those of every other mother of a large family having a small income.

Financially, my problem is to shelter, feed, clothe, educate, provide amusement and keep in health a family of eleven on an average income of fifteen hundred dollars per year.

Physically—to keep enough energy in one hundred and twenty pounds of human flesh to cook, wash, scrub, make and mend the clothes, nurse, and do all the other numerous jobs for the family.

Mentally—to assist with lessons.

Morally—to keep from slighting the pots and pans that I may satisfy my selfish longing to practice for a few minutes the music that was such a part of my life of the days gone by. Also, to keep from saying ugly words when everything goes wrong.

Spiritually—to keep my soul clean when the surroundings are dirty. To be sweet and cheerful when I don’t even have time to say my prayers.

All of these jobs were possible in a way so long as I could see the “vision”; but that is the greatest problem of all. As the years have passed, so has it gone. Like the mirage of the weary desert traveler, it has gradually faded from my sight. Who can help me to regain it?

No time to train my children, and now the traits of heredity and environment are mocking me. No money to give them anything but the bare necessities of life, so that they are trained for no special work. No energy left, after the day’s work, to play with them, so that we have grown far apart.

Can someone devise a plan by which the world may keep going without the bulk of the labor falling on the weakest shoulders?

The Things I Want to Do

My personal problem is the old riddle inverted: “How can a woman not a housekeeper be a housekeeper?” It is rather a spiritual than a material problem, and is of course harder to solve. Even though I reduce my household duties to such a system that I get through them quite creditably, how can I find inspiration and happiness in them, when there are other things I want to do and can do better? I want to write; I know full well that I am not a genius, or I would write; but I love to. But I must do my housework, and by the time the afternoon leisure comes those things which bubbled and glowed with life in the morning have about the consistency and elasticity of a cold fried egg.

I would not change my lot if it meant giving up home and children; I am convinced that there is nothing in the world that can remotely compare with the joys of parenthood. But if there is any way in which one may fulfill one’s destiny in that respect, and in lesser ways also, may the Companion be successful in helping us find it. . . .

The Unbroken Circle

$25 Prize-Winner

For two weeks I’ve taken down my Companion every night and reread the conditions about this letter and dropped to sleep with my head on my desk from sheer weariness before I had written a single line. I am cook, housemaid, laundress, and nurse for my family of four, and this morning I’ve parked my baby with a neighbor for an hour in order to add my problem to those up for solution.

My husband is a teacher and our income is from thirty to fifty dollars short of comfort every month. There is no hope of a change in this matter for years to come, unless I can do it myself. Like most teachers, my husband is absorbed in his work and would be the most surprised person in the world if he knew I was writing this letter.

My children are bright and normal in every way and I love them dearly, but I know there isn’t a woman who will read this letter who doesn’t understand me when I say that I have no personal life. I am only a piece of machinery that nobody realizes the value of, unless I should stop. There are three people who look to me for nourishing food, for clean, mended clothes, for a tidy home, and for an audience. It is an endless circle with no break in it where I personally come in at all.

Now the question is, when shall I take my time off? That is what I need most, just a short time every day when my whole family can be comfortably out of my thoughts and sight, and I can rest or read or shop or visit, and in some way spend a little while just building up my own life. I do not consider my life especially hard. There are too many other women doing the same thing; but I am just past my thirtieth birthday, and my hair is noticeably gray, my shoulders droop a little, and my eyes show that I haven’t had a real thrill in months or years. . . .

“A Woman Does Not Need Money”

I am a farmer’s wife, the mother of six children, the eldest only twelve years and the youngest eleven months, and just two years between all their ages.

I hardly know how I want to write, so it won’t seem I am a fault-finder. But I have tried to keep up my end of the work, and my husband just seems to take it for granted that I am made of iron and it is my place to do the work, that I don’t ever need recreation, or money either.

When a woman does her work of caring for her home and children and the thousand other things she has to do, I think she does her part. But I have done all these, and worked in the fields besides. Last year my son and I hoed fifteen acres of cotton over three times, and my baby stayed in the shade of a tree at the end of the rows with only the other children to care for him. He was only four and one half months old then. I have had to do that ever since I was married, thirteen years ago; and have ruined my health by doing so, too.

It wouldn’t be so hard if he would show his appreciation of my work, and give me a little recreation and money to spend on myself and children. He says a woman does not need money. When he needs any farming tools he goes and gets them. When I ask for money to buy something for the home, he says we can make out without that. When he gets ready to go anywhere, let it be far or near, he goes. He always has money for all his needs.

We own our farm of twenty-five acres, and I have helped pay for it in more ways than one and think I am entitled to my part of the income; but have given in in all things, rather than live in a quarrel, until I have about lost interest in life and think the game isn’t worth the candle. You may think I could sell the butter, eggs, and chickens—well, there is always something to buy for the table with all I get for these things. . . .

Equalizing the Burdens

An article appeared recently in a current magazine entitled “Don’t Be a Door Mat.” I read it with interest and resolved that I would not any longer. But how was I to escape without neglecting my responsibilities in the rearing of two small children, the housework of a seven-room flat, and being a true wife to my husband, when our income would not permit the hiring of help? It was, and still is, a problem; but a solution presented itself to me and I believe in our case, at least, it is the correct one.

I wonder if any of us have ever counted the number of hours we put into the daily round of tasks, and the amount of our leisure time. I tried to, but failed. It would have required an expert; but this much I knew: I was working at least four hours a day more than my husband. Why was I required to do this? Isn’t married life an equal partnership, or supposed to be? It was not in our case; but I proposed to make it so.

Realizing that much unpleasantness in married life has been caused because the wife carries the greater burden and gradually loses her early ideals of marriage, I decided to approach the matter diplomatically. It was not selfishness or laziness on my husband’s part that restrained him from helping with the dishes after dinner or washing the kitchen floor on Saturday afternoons; it was that old, old fallacy that those were woman’s tasks, and did not concern him. He had been brought up that way, even as I had. I knew that he loved me dearly, and that if the matter was presented to him in the proper light all would be well.

After pondering over the subject for several days and rejecting several ways which occurred, I resolved to bury my pride and put him to the test by asking him to help me.

“Jim,” I said one evening as he had just settled in his favorite chair and picked up the paper, “I have a big ironing to do tonight; will you help me get the dishes out of the way?” Maybe my voice had a quake in it as I finished and it caught his attention, but anyhow he looked up, hesitated a minute, and then in a wholehearted way said, “Why, sure I will.” It was not so hard the next time to ask him to help. Gradually he came to see the injustice of it all, and now he has this viewpoint—that as long as he cannot afford to hire help, it is his duty to help me himself. . . .

“She Has Used Herself Up”

It is a recognized fact that in many organizations, like Parent-Teachers Associations, Girl Scout and Boy Scout work and welfare work, it is the mothers of the community who are most effective and who are best prepared in hand and brain. But these mothers have less time for outside work than any other class of women. One friend of mine, a college woman and a teacher before her marriage, is the fond and capable mother of four boys. Her mind is teeming with ideas for her children and her community: ways to improve the schools; a plan for better milk inspection; neighborhood club for boys and their fathers; plan for cooperative buying among housewives. All these she could adequately carry out, for she is a born leader. But, after her manual labor is through for the day, she has not an ounce of energy left—she has used herself up in doing the work necessary to keep her boys and husband fed and her house in decent order. What is the solution for the women of limited income and unlimited brains?

The world needs all the help it can get from intelligent wives and mothers, and the wives and mothers need help for the necessary household tasks. May the solution soon appear!

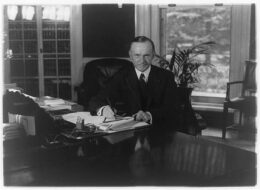

Annual Message to Congress (1923)

December 06, 1923

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.