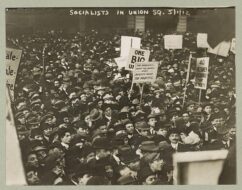

When the war cut off the traditional flow of immigrant labor to the United States, northern factory recruiters headed south with enticing offers of higher wages and better jobs. Moving north held particular appeal for the 500,000 Black southerners who migrated with hopes of escaping the stifling embrace of southern Jim Crow laws. The Chicago Defender played a key role in the Great Migration by urging Black southerners to move north and then offering them advice once they arrived. The arrival of southern migrants revealed class and regional tensions within the African American community as middle-class, urban, educated northerners often bristled at the “country” habits of the new arrivals. This article was one of many “do and don’t” lists that the Black newspaper published emphasizing respectability, thrift, cleanliness, and sobriety.

Despite the absence of legalized segregation, the North still maintained unspoken rules of racial etiquette that could be hard for newcomers to discern. By helping migrants prosper, Black middle-class advice-givers were striving to protect the limited economic and political foothold that African Americans had achieved. They also hoped to avoid transgressions that might give whites an excuse to instigate racial violence. There was reason for concern. On July 27, 1919, two months after this article was published, a Black teenager mistakenly swam over an imaginary line that segregated swimming areas of Lake Michigan and was stoned to death by whites standing on the beach. In the ensuing race riot, Black residents took up arms in a show of determined self-defense.

—Jennifer D. Keene