No related resources

Introduction

Founded in 1890, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) initially focused on amending state constitutions one by one to include female suffrage. Embracing a states’ rights philosophy, NAWSA argued that states could allow women to vote and still maintain other forms of voting restrictions, including poll taxes and citizenship, residency, and education requirements. In 1912, newcomers Alice Paul (1885–1977) and Lucy Burns (1879–1966) secured lukewarm support from NAWSA leaders to begin lobbying for a federal constitutional amendment. Four years later the pair left NAWSA and formed a competing organization, the National Woman’s Party (NWP), dedicated solely to securing a federal amendment (see Alice Paul in Prison).

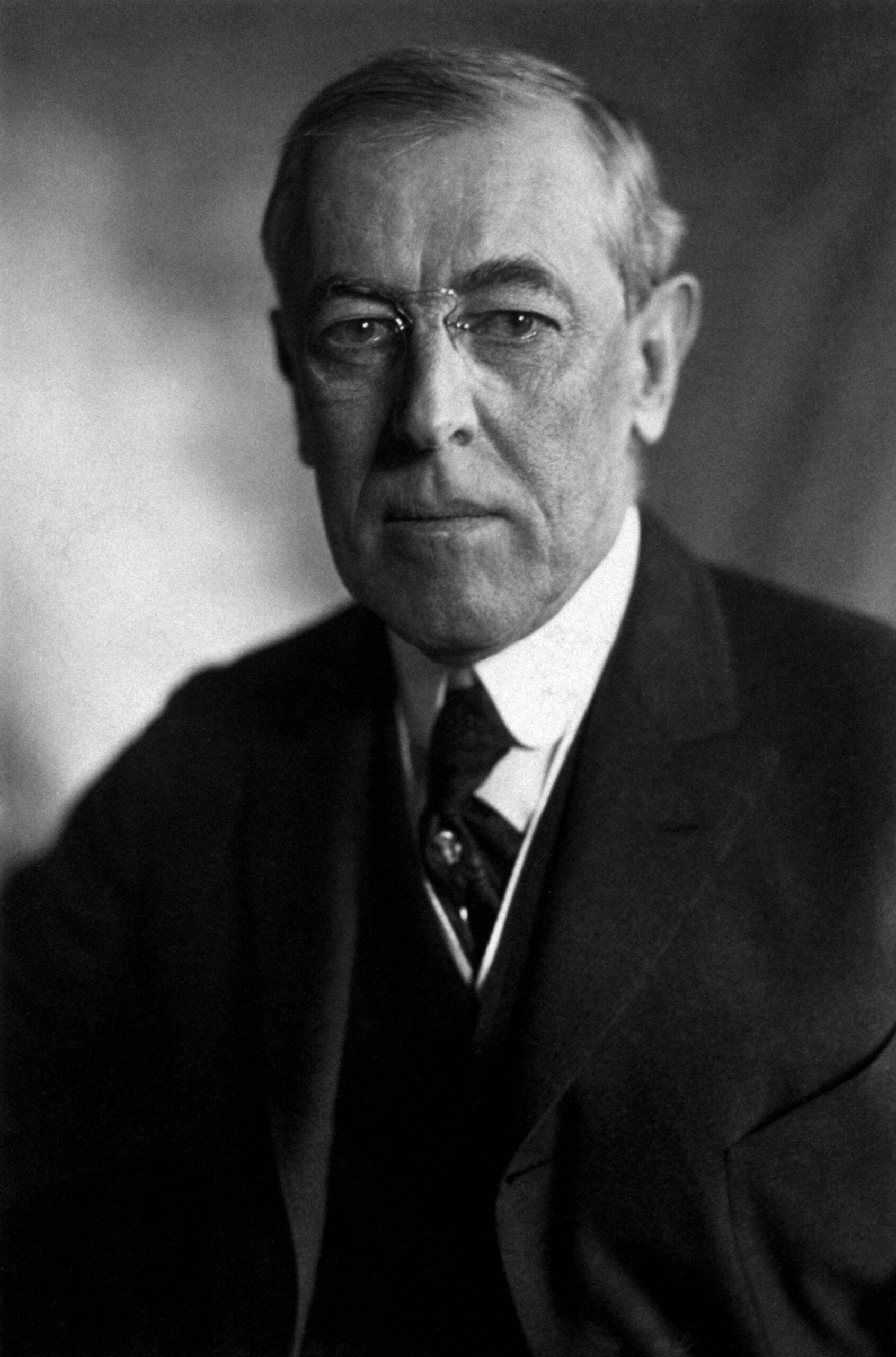

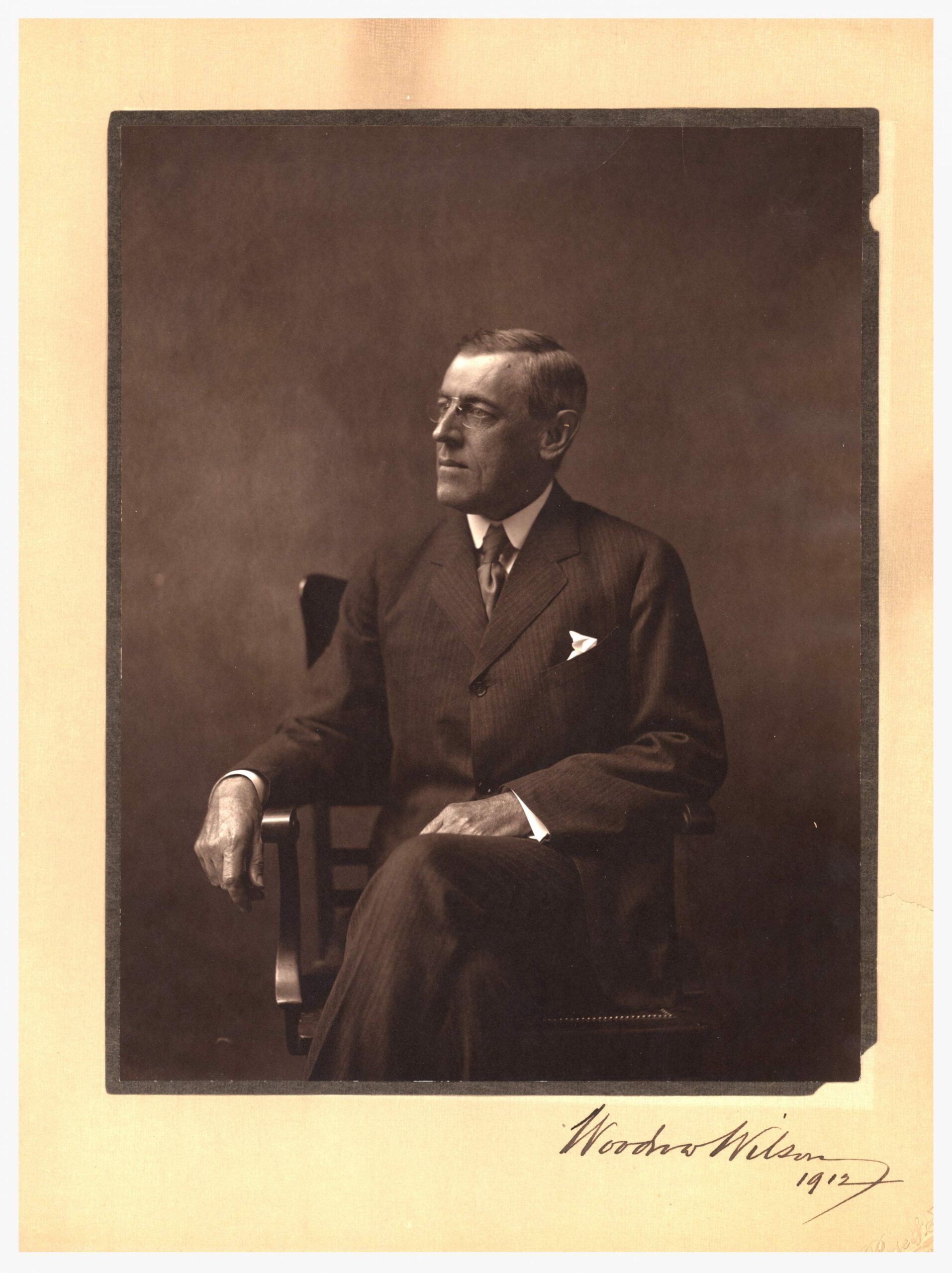

Carrie Chapman Catt (1859–1947) served as NAWSA president from 1915 to 1920. In 1916 Catt announced her “Winning Plan,” which entailed lobbying simultaneously for suffrage on the state and federal levels. After New York adopted female suffrage on November 6, 1917, Catt wrote this open address to Congress which she delivered as a public speech several times. A skilled political strategist, Catt encouraged NAWSA members to volunteer for wartime food conservation and liberty loan committees to strengthen the argument for female suffrage. President Wilson (1856–1924) appeared to vindicate Catt’s approach when he publicly endorsed a constitutional amendment in September 1918, arguing “we have made partners of the women in this war. . . . Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” The NWP, however, believed that its militant tactics had forced Wilson to become the first sitting president to support female suffrage.

Carrie Chapman Catt, “Open Address to the U.S. Congress,” November 1917, Archives of Women’s Political Communication, Iowa State University. Available at https://awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/2017/03/21/address-to-congress-november-1917/.

Woman suffrage is inevitable. Suffragists knew it before November 6, 1917; opponents afterward. . . . Ours is a nation born of revolution; of rebellion against a system of government so securely entrenched in the customs and traditions of human society that in 1776 it seemed impregnable. From the beginning of things nations had been ruled by kings and for kings, while the people served and paid the cost. The American Revolutionists boldly proclaimed the heresies:

“Taxation without representation is tyranny.”

“Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.”. . .

The Logic of the Situation Calls for Immediate Action

Is it not clear that American history makes woman suffrage inevitable? That full suffrage in twelve states makes its coming in all forty-eight states inevitable?1 That the spread of democracy over the world, including votes for the women of many countries, in each case based upon the principles our Republic gave to the world, compels action by our nation? Is it not clear that the world expects such action and fails to understand its delay?

In the face of these facts we ask you, senators and members of the House of Representatives of the United States, is not the immediate enfranchisement of women of our nation the duty of the hour?

Why hesitate? Not an inch of solid ground is left for the feet of the opponent. . . .The million and fifteen thousand women of New York who signed a declaration that they wanted the vote, plus the heavy vote of women in every state and country where women have the franchise, have finally and completely disposed of the familiar “they don’t want it” argument. Thousands of women annually emerging from the schools and colleges have closed the debate upon the one-time serious “they don’t know enough” argument. The statistics of police courts and prisons have laid the ghost of the “too bad to vote” argument. . . .The testimony of thousands of reputable citizens of our own suffrage states and of all other suffrage lands that woman suffrage has brought no harm and much positive good, and the absence of reputable citizens who deny these facts, has closed the “women only double the vote” argument. The increasing number of women wage-earners, many supporting families and some supporting husbands, has thrown out the “women are represented” argument. . . .

If enfranchisement is to be given to women now, how is it to be done? Shall it be by amendment of state constitutions or by amendment of the federal Constitution? There are no other ways. The first sends the question from the legislature by referendum to all male voters to the state; the other sends the question from Congress to the legislature of the several states. . . .

We elect the federal method. There are three reasons why we make this choice and three reasons why we reject the state method. We choose the federal method (1) because it is the quickest process and justly demands immediate action. If passed by the Sixty-fifth Congress, as it should be, the amendment will go to forty-one legislatures in 1919, and when thirty-six have ratified it, will become a national law. . . .

(2) . . . For the first time in our history Congress has imposed a direct tax upon women and has thus deliberately violated the most fundamental and sacred principle of our government, since it offers no compensating “representation” for the tax it imposes. Unless separation is made it becomes the same kind of tyrant as was George the Third. When the exemption for unmarried persons under the Income Tax was reduced to $1,000, the Congress laid the tax upon thousands of wage-earning women—teachers, doctors, lawyers, bookkeepers, secretaries, and the proprietors of many businesses. . . .The national government is guilty of the violation of the principle that the tax and the vote are inseparable; it alone can make amends. Two ways are open: exempt the women the Income Tax or grant them the vote—there can be no compromise. . . .

(3) If the entire forty-eight states should severally enfranchise women, their political status would still be inferior to that of men, since no provision for national protection in their right to vote would exist. . . . By the state method, thirty-six states would be obliged to have individual campaigns, and those would still have to be followed by the forty-eight additional campaigns to secure the final protection in their right to vote by the national government. We propose to conserve money, time, and woman’s strength by the elimination of the thirty-six state campaigns as unnecessary to this stage of the progress of the woman suffrage movement. . . .

Our nation is in the extreme crisis of its existence and men would search their very souls to find just and reasonable causes for every thought and act. If you, making this search shall find “state’s rights” a sufficient cause to lead you to vote “no” on the Federal Suffrage Amendment, then, with all the gentleness which should accompany the reference to a sacred memory, let us tell you that your cause will bear neither the test of time nor critical analysis, and that your vote will compel your children to apologize for your act.

Already your vote has forwarded some of the measures which are far more distinctly state rights questions than the fundamental [demand] for equal human rights. Among such questions are the regulation of child labor, the eight-hour law, the white slave traffic, moving picture, questionable literature, food supply, clothing supply, Prohibition. All of these acts are in the direction of the restraint of “personal liberty” in the supposed interest of the public good. Every instinct of justice, every principle of logic and ethics is shocked at the reasoning which grants Congress the right to curtail personal liberty but no right to extend it. “Necessity knows no law” may seem to you sufficient authority to tax the incomes of women, to demand exhausting amounts of volunteer military service, to commandeer women for public work and in other ways to restrain their liberty as war measures. But by the same token the grant of more liberty may properly be conferred as a war measure. If other lands have been brave enough to extend suffrage to women in war time, our own [country], the mother of democracy, surely will not hesitate.2 We are told that a million or more American men will be on European battle fields ere3 many months. For every man who goes, there is one loyal woman and probably more who would vote to support to the most that man’s cause. The disloyal men will be here to vote. Suffrage for women now as a war measure means suffrage for the loyal forces for those who know what it means “to fight to keep the world safe for democracy.”

The framers of the Constitution gave unquestioned authority to Congress to act upon women suffrage. Why not use that authority and use it now to do the big, noble, just thing of catching pace with other nations on this question of democracy? The world and posterity will honor you for it. . . .

- 1. By 1917, women had full voting rights in twelve states: Wyoming (1890), Colorado (1893), Utah (1896), Idaho (1896), Washington (1910), California (1911), Arizona (1912), Kansas (1912), Oregon (1912), Montana (1914), Nevada (1914), and New York (1917). Michigan, Oklahoma, and South Dakota followed in 1918, two years before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.

- 2. By 1917, women could vote in New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and Russia. Great Britain had promised to enact limited woman suffrage.

- 3. Ere means before.

Annual Message to Congress (1917)

December 04, 1917

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.