No related resources

Introduction

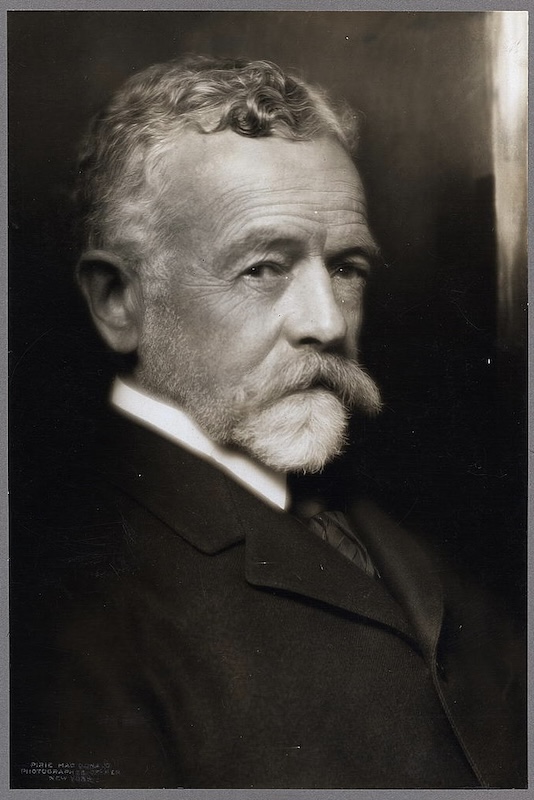

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (1850–1924; R–MA) and President Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924) disagreed vehemently over what shape the postwar peace should take. The Versailles Peace Treaty imposed harsh terms on a defeated Germany and created a new League of Nations to handle future international disputes. Lodge chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (which managed the Senate ratification process) and was therefore a powerful opponent. It did not help negotiations that Lodge and Wilson detested each other. Lodge viewed Wilson as sanctimonious; Wilson thought Lodge was narrow-minded.

Although Lodge opposed numerous clauses of the Versailles Peace Treaty, he was not an isolationist. Instead, he believed that rebuilding the European balance of power system (with American involvement) would contain Germany better than the proposed League of Nations would. Rather than urging outright rejection of the treaty, Lodge initially proposed adding fourteen reservations (a jab at Wilson’s Fourteen Points). The most significant modification was requiring explicit congressional approval before sending American troops abroad. Wilson rejected Lodge’s proposals outright.

The stand-off between Lodge and Wilson centered on conflicting interpretations of Article 10 of the League Covenant, a clause that contained only two sentences: “The Members of the League undertake to respect and preserve as against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all Members of the League. In case of any such aggression or in case of any threat or danger of such aggression the Council shall advise upon the means by which this obligation shall be fulfilled.”

In this speech to Congress, Lodge outlined his interpretation of Article 10 and his other objections to the League. Defending the Versailles Peace Treaty contains Wilson’s counterpoint

Source: Congressional Record, 66th Congress, 1st Session, 3779–3784. Available at: www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-FCIC/pdf/GPO-FCIC.pdf

. . . If Europe desires such an alliance or league with a power of this kind, then so be it. I have no objection, provided they do not interfere with the American continents or force us against our will but bound by a moral obligation into all the quarrels of Europe. If England, abandoning the policy of Canning,1 desires to be a member of a league which has such powers as this, I have not a word to say. But I object in the strongest possible way to having the United States agree, directly or indirectly, to be controlled by a league which may at any time, and perfectly lawfully and in accordance with the terms of the covenant, be drawn in to deal with the internal conflicts in other countries, no matter what those conflicts may be. We should never permit the United States to be involved in the internal conflict in another country, except by the will of her people expressed through the Congress which represents them.

With regard to wars of external aggression on a member of the league, the case is perfectly clear. There can be no genuine dispute whatever about the meaning of the first clause of article 10. In the first place, it differs from every other obligation in being individual and placed upon each nation without the intervention of the league. Each nation for itself promises to respect and preserve as against external aggression the boundaries and the political independence of every member of the league….

It is, I repeat, an individual obligation. It requires no action on the part of the league, except that in the second sentence the authorities of the league are to have the power to advise as to the means to be employed in order to fulfill the purpose of the first sentence. But that is a detail of execution, and I consider that we are morally and in honor bound to accept and act upon that advice. The broad fact remains that if any member of the league suffering from external aggression should appeal directly to the United States for support the United States would be bound to give that support in its own capacity and without reference to the action of other powers, because the United States itself is bound, and I hope the day will never come when the United States will not carry out its promises. If that day should come, and the United States or any other great country should refuse, no matter how specious the reasons, to fulfill both in letter and spirit every obligation in this covenant, the United States would be dishonored and the league would crumble into dust, leaving behind it a legacy of wars. If China should rise up and attack Japan in an effort to undo the great wrong of the cession of the control of Shantung2 to that power, we should be bound under the terms of article 10 to sustain Japan against China, and a guaranty of that sort is never involved except when the question has passed beyond the stage of negotiation and has become a question for the application of force. I do not like the prospect. It shall not come into existence by any vote of mine. . . .

Those of us, Mr. President [of the Senate], who are either wholly opposed to the league, or who are trying to preserve the independence and the safety of the United States by changing the terms of the league, and who are endeavoring to make the league, if we are to be a member of it, less certain to promote war instead of peace have been reproached with selfishness in our outlook and with a desire to keep our country in a state of isolation. So far as the question of isolation goes, it is impossible to isolate the United States. I well remember the time, twenty years ago, when eminent senators and other distinguished gentlemen who were opposing the Philippines and shrieking about imperialism sneered at the statement made by some of us, that the United States had become a world power.3 I think no one now would question that the Spanish war marked the entrance of the United States into world affairs to a degree which had never obtained before. It was both an inevitable and an irrevocable step, and our entrance into the war with Germany certainly showed once and for all that the United States was not unmindful of its world responsibilities. We may set aside all this empty talk about isolation. Nobody expects to isolate the United States or to make it a hermit nation, which is a sheer absurdity. But there is a wide difference between taking a suitable part and bearing a due responsibility in world affairs and plunging the United States into every controversy and conflict on the face of the globe. By meddling in all the differences which may arise among any portion or fragment of humankind we simply fritter away our influence and injure ourselves to no good purpose. We shall be of far more value to the world and its peace by occupying, so far as possible, the situation which we have occupied for the last twenty years and by adhering to the policy of [George] Washington and [Alexander] Hamilton, of [Thomas] Jefferson and [James] Monroe, under which we have risen to our present greatness and prosperity. The fact that we have been separated by our geographical situation and by our consistent policy from the broils of Europe has made us more than any one thing capable of performing the great work which we performed in the war against Germany and our disinterestedness is of far more value to the world than our eternal meddling in every possible dispute could ever be.

Now, as to our selfishness, I have no desire to boast that we are better than our neighbors, but the fact remains that this nation in making peace with Germany had not a single selfish or individual interest to serve. All we asked was that Germany should be rendered incapable of again breaking forth, with all the horrors incident to German warfare, upon an unoffending world, and that demand was shared by every free nation and indeed by humanity itself. For ourselves we asked absolutely nothing. We have not asked any government or governments to guarantee our boundaries or our political independence. We have no fear in regard to either. We have sought no territory, no privileges, no advantages for ourselves.4 That is the fact. It is apparent on the face of the treaty. I do not mean to reflect upon a single one of the powers with which we have been associated in the war against Germany, but there is not one of them which has not sought individual advantages for their own national benefit. I do not criticize their desires at all. The services and sacrifices of England and France and Belgium and Italy are beyond estimate and beyond praise. I am glad they should have what they desire for their own welfare and safety. But they all receive under the peace territorial and commercial benefits. We are asked to give, and we in no way seek to take. Surely it is not too much to insist that when we are offered nothing but the opportunity to give and to aid others we should have the right to say what sacrifices we shall make and what the magnitude of our gifts shall be. In the prosecution of the war we gave unstintedly American lives and American treasure. When the war closed we had 3,000,000 men under arms. We were turning the country into a vast workshop for war. We advanced ten billions to our allies. We refused no assistance that we could possibly render. All the great energy and power of the Republic were put at the service of the good cause. We have not been ungenerous. We have been devoted to the cause of freedom, humanity, and civilization everywhere. Now we are asked, in the making of peace, to sacrifice our sovereignty in important respects, to involve ourselves almost without limit in the affairs of other nations and to yield up policies and rights which we have maintained throughout our history. We are asked to incur liabilities to an unlimited extent and furnish assets at the same time which no man can measure. I think it is not only our right but our duty to determine how far we shall go. Not only must we look carefully to see where we are being led into endless disputes and entanglements, but we must not forget that we have in this country millions of people of foreign birth and parentage.

Our one great object is to make all these people Americans so that we may call on them to place America first and serve America as they have done in the war just closed. We cannot Americanize them if we are continually thrusting them back into the quarrels and difficulties of the countries from which they came to us. We shall fill this land with political disputes about the troubles and quarrels of other countries. We shall have a large portion of our people voting not on American questions and not on what concerns the United States but dividing on issues which concern foreign countries alone. That is an unwholesome and perilous condition to force upon this country. We must avoid it….

- 1. George Canning (1770–1827) was a British foreign secretary who supported an independent British foreign policy and balance of power system in Europe.

- 2. In 1897 China conceded the province of Qingdao to Germany. In 1914 Japan declared war on Germany and attacked Qingdao, giving China assurances that the territory would be returned. During the attack, Japan expanded the war zone to include the Shandong (Shantung) Peninsula and built a settler colony there during its occupation. Seeking Japan’s support for the League of Nations, Wilson agreed to let Japan to keep Shandong, after which China refused to sign the Versailles Peace Treaty. In 1922, bowing to international pressure, Japan returned the territory to China but continued to maintain a military presence.

- 3. The United States annexed the Philippines as a colony after the Spanish-American War (1898), provoking heated debate between imperialists and anti-imperialists, and igniting the Philippine-American War (1899–1902).

- 4. Lodge was referring to clauses in the Paris peace treaties that required Germany to pay reparations to the Allied nations and dismantled the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian empires to create independent nations or new colonies/zones of influence for the victors.

Defending the League of Nations: “The Pueblo Speech”

September 25, 1919

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.