Introduction

In 1851, Maine became the first state to adopt a statewide ban on the manufacture and sale of liquor. A number of states passed similar laws during the 1850s. States also adopted prohibition laws in the 1880s and then again during the 1900s–1910s. In some cases, states repealed these laws several years after adopting them; other states maintained prohibition policies for an extended time. In 1917 Congress proposed the Eighteenth Amendment, which adopted a nationwide policy prohibiting the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” By 1919 a sufficient number of states had ratified the amendment to ensure its adoption, and Congress then passed the Volstead Act defining intoxicating liquors and providing means of enforcing the amendment, which took effect in 1920.

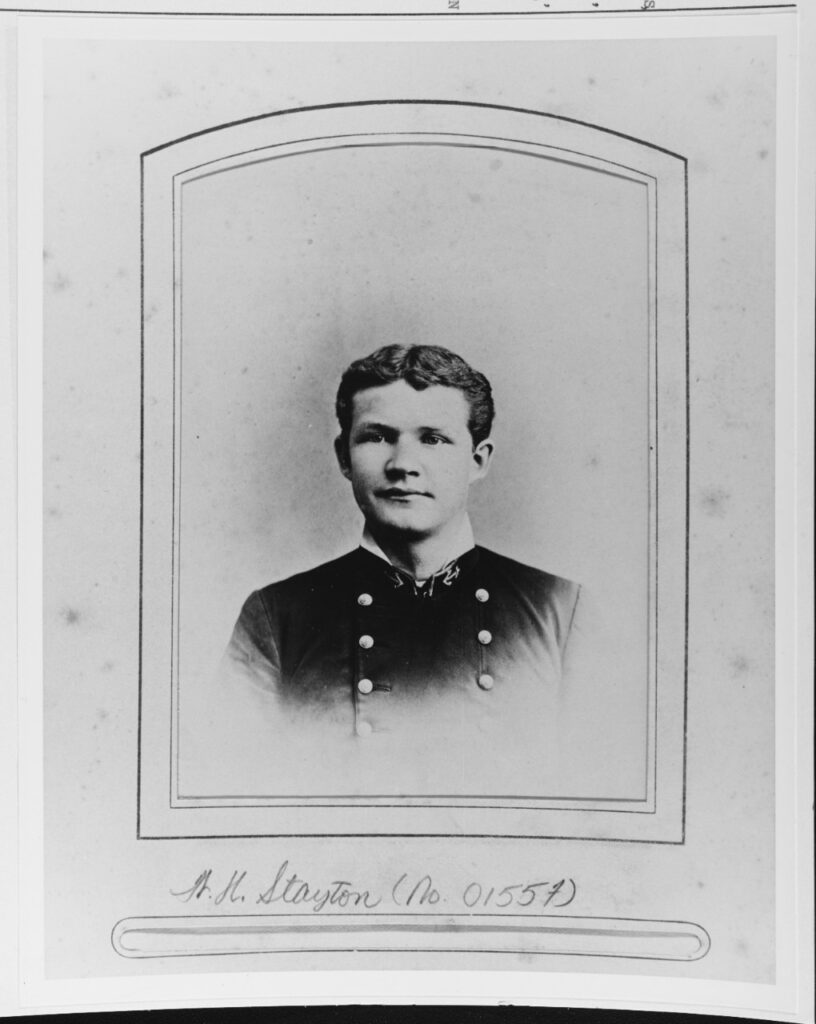

In 1918 William H. Stayton, a former U.S. Navy captain, founded the Association against the Prohibition Amendment, which sought initially to prevent passage of the Eighteenth Amendment and later worked to bring about its repeal. The amendment was eventually repealed in 1933 via the Twenty-First Amendment. In this 1923 article, Stayton argued that national prohibition had been ineffective, in large part because it ran counter to the principles and traditions of the American federal system and the importance of local self-government and personal liberty. Public support for and acquiescence in policies such as prohibition was much greater, Stayton argued, when policies were promulgated at the state level.

—John Dinan

... The federal government was created to deal with only those functions which could not well be handled by a single state. International affairs were a fit subject for federal power, as were such matters as interstate commerce, affecting more than one state. But the very spirit of the Constitution was that each state should forever keep power over its local affairs. This spirit has been destroyed by the Eighteenth Amendment, under which the right of local self-government is torn from the individual states, whose people are made subject, even in the small routine affairs of their daily lives, to those living in far distant localities and under other conditions.

And this brings us to a vital point, going to the very foundations of federations such as ours. A geographically small country with a homogeneous population may endure sumptuary laws1 which are uniform through the land. But the United States, with its northermost point far up in the Arctic, stretches through the temperate zone, thence through the northern tropics, past the Equator and deep into the southern tropics, and from east to west we extend more than half way around the earth. We have become a huge country embracing vast climatic ranges, and including in the Union people of diverse origins, differing physically and in faiths, thoughts, and habits.

Obviously, to hold such dissimilar groups in happy combination, there must be the fullest practicable measure of local self-government and personal liberty, and there must be tolerance and toleration, a kindly national spirit of give and take. For any one sect or section to impose by force its sumptuary views, however worthy, upon those of different thought must necessarily lead to misunderstandings, setting class against class, and tend toward disintegration. Cool-headed Americans can hardly fail to see today the operation of this tendency.

Those dwelling in large cities and trying earnestly to solve the pressing problems of life under hive conditions feel that impracticable regulations have been forced upon them through the vote of those living in rural communities and happily unable to hear nature’s cry from the crowded tenement. Nor is the city man unaware that, while the Enforcement Division denies him even his mild beverages, yet it, relying upon the rural vote for support, has failed to issue like regulations for the country districts, and continues to permit the farmer to have his hard cider, his home-made wines, and his fermented juices. Thus is enmity born between rural and urban brothers, and thoughtful citizens may well take heed now lest retaliations follow when comes the inevitable day in which the city vote will be in the majority.

... Another collateral result of Volsteadism2—one utterly unexpected by the prohibitionists—is widely manifesting itself in disrespect for law, which has become so grave that President Harding called it the “most demoralizing factor” in our public life.

The prohibitionists cry out that the people are wrong and should obey the law. The people answer that it is the law which is wrong, and should be changed. Certain it is that either the law is wrong and should be changed or the people are wrong and should be changed. And the voters will sooner or later have to decide which of these jobs they will undertake.

Why this law should be held in such contempt by people who are otherwise law-abiding is still a matter of controversy. Some condemn it for one reason, some for another. A leading New England newspaper sees in the public’s attitude a warning that we should “begin a serious study of all laws which do not command public favor” because in a republic “a law which does not command public support is not a law—it is a form of tyranny.”

One who studies the psychology of the subject is inevitably struck by the anomaly that while state prohibition laws were generally obeyed and respected, people seem to feel it a sort of duty to flout the Volstead Act. And inquiry quickly reveals at least one reason—a belief that the law was passed not by a man’s neighbors, who had an interest in him and his affairs, but by someone living at a distance, by strangers acting in a spirit of meddlesomeness. The Marylander is quite willing to yield even respect and obedience to a law he believes oppressive, provided it was passed by his own people, but his innate sense of independence resents the effort of Kansans to impose a law on him through what he believes to be a smug piece of sanctimonious humbuggery. “If Kansans,” he says, “want prohibition and believe it good for their people, let them have it by all means; but why should Kansas meddle with Maryland? I am not forcing anything on her against her will and I’ll not have her force something on me.”

No good can come from merely berating the public because a law is disobeyed. There are two sides to the subject. Undoubtedly there is an obligation on all of us to obey the law, but in a free country there is a corresponding obligation on the part of the lawmaking bodies to enact only such measures as are fair and reasonable and will command the support of public opinion. Those lawmakers who foisted national prohibition upon us committed the first and the great wrong, and upon them rests the responsibility for our present lawlessness....