No related resources

Introduction

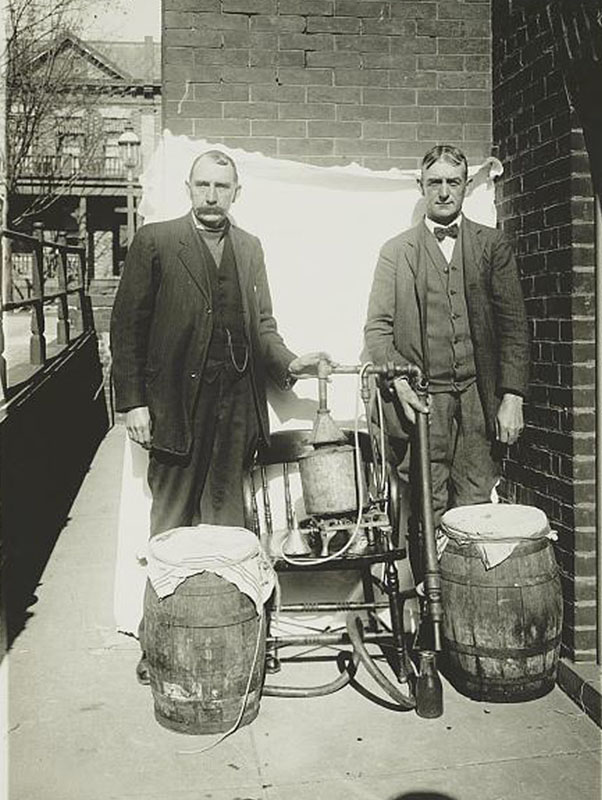

In the early 1900s, Americans’ alcohol consumption exploded. Saloons proliferated, and these male-only drinking establishments often served as headquarters for the corrupt political machines that controlled local politics. Temperance advocates linked excessive drinking to other social ills, including domestic abuse, crime, poverty, and prostitution—the latter held largely responsible for the unchecked spread of sexually transmitted diseases. The wide publicity given to these evils helped the temperance movement build national support for adoption of the Eighteenth Amendment (1919), which banned the sale, manufacture, and transportation of intoxicating liquors.

The quickly enacted Volstead Act (1919) defined any beverage with more than 0.5 percent alcohol as intoxicating liquor and established criminal penalties for manufacturing, transporting, or possessing alcohol (while allowing for private home consumption, sacramental wine, and medicinal liquor). Brewers, who had expected only hard liquors to fall into the prohibited category, were not the only Americans surprised by the severity of the law. In 1925, the North American Review printed a series of essays evaluating the impact of national Prohibition. he following excerpts offer a sampling of the arguments put forth by supporters of Prohibition, known as “drys,” and opponents, or “wets.” The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed in 1933 when the Twenty-first Amendment was added to the Constitution.

James P. Holland, “The Workingman’s View of Prohibition,” North American Review, vol. 220, no. 827 (June 1, 1925), 611–614. Available at https://archive.org/details/sim_north-american-review_june-august-1925_221_2/page/610/mode/2up; Samuel Harden Church, “The Paradise of the Ostrich,” North American Review, vol. 220, no. 827 (June 1, 1925), 625–630. Available at https://archive.org/details/sim_north-american-review_june-august-1925_221_2/page/624/mode/2up; Wayne B. Wheeler, “Is There Prohibition? And to What Extent?” North American Review, vol. 222, no. 828 (September 1, 1925), 29–34. Available at

https://archive.org/details/sim_north-american-review_september-november-1925_222_828/page/28/mode/2up; Cornelia James Cannon, “Prohibition and the Younger Generation,” North American Review, vol. 222, no. 828 (September 1, 1925): 65–68. Available at https://archive.org/details/sim_north-american-review_september-november-1925_222_828/page/64/mode/2up.

The Workingman’s View of Prohibition

by James P. Holland1

President of the New York State Federation of Labor

To write an article dealing with the effects of Prohibition from the standpoint of the workingman seems to be quite a futile undertaking. Prohibition has reached the point where it must be dealt with from the standpoint of the American citizen, without particular regard to any class of our citizenry.

The workingman, as an American citizen, still clings to the idea that the American theory of government, even if not perfect, is yet by far the best ever devised by the sons of man. The workingman still holds that the American people are capable of self-government, not only politically, but individually and morally. The workingman needs no sumptuary laws2 for his political or moral salvation. He holds that sumptuary laws of any kind have no place in the American theory of government.

And further, the workingman is aware that sumptuary laws—such as the Prohibition amendment—are generally enacted for his particular benefit, and to help him to lead a “moral” life, to protect him from this, that and the other thing. He resents this patriarchal attitude of the lessees3 of all goodness and morality, such as the Anti-Saloon League,4 and demands the liberty to shape his own standards of life, now and hereafter. He rejects the inferiority complex which is foisted upon him by “benevolent” employers with the aid of professional reformers.

If there is any one body especially competent to define the general attitude of the workingman toward Prohibition, then it is the conventions of the American Federation of Labor.5 Beginning with the convention at Atlantic City, the American Federation of Labor has gone on record as opposed to the Eighteenth Amendment, and advocating the modification of the Volstead law. The Executive Council and the president of the American Federation of Labor have been instructed to work in this direction. Representation has been made to the president of the United States and to the Congress for relief from the drastic provisions of the amendment and the Volstead law.

No normal-minded man will seriously deny the curse and evil of intemperance—not only in drinking, but in many other habits. The virtue of temperance in all things needs no particular elucidation. But five years of national Prohibition give us the proof that the ideal of temperance cannot be achieved through coercion, assumption, fanaticism or governmental tyranny. In fact, through all phases of its development, from local option6 to nation-wide Prohibition, it has proved an absolute and dismal failure. In no case have such laws ever gained voluntary obedience, and never has it been possible to enforce obedience.

The Prohibition Amendment is an unreasonable and unnatural law. There is no use at all in discussing the question, whether or not it can be enforced. It cannot. Obedience to any and all laws is not at all such a great virtue as some people try to make believe. In fact, all that is good in governmental theory and practice throughout the world is due to disobedience of unreasonable, unnatural and consequently tyrannic laws. The Fathers of our own Republic, who made the original Constitution, knew that sumptuary laws are against Nature. That is the reason why they kept the power to make such laws out of the original Constitution by an overwhelming vote. . . .

The Paradise of the Ostrich

by Samuel Harden Church7

President, Carnegie Institute

Finding myself seated one night at dinner beside a United States judge who possesses one of the greatest judicial minds that our country has produced in this generation, I asked him what he thought of Prohibition. “Regardless of what your feelings may be concerning the use of liquor,” he replied, “the American people made the greatest mistake in the world when they inserted the statute itself in the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution. The amendment should have given Congress the power to legislate for it, or against it, or to prohibit it, in accordance from time to time with the changing views of the people. But now that they have got the statute itself in there, it will be difficult to get it out, and in the meantime”—and his deep-seated eyes, sparkling with humor, fastened themselves upon a man across the table who was at that moment raising a glass of wine to his lips—“in the meantime— there you are!”

And that, indeed, is just where we are! Moved by the deep emotions of the war, we have indolently permitted a well-organized and enormously financed body composed of zealots, fanatics and bigots, together with their paid orators and professional agitators, the whole of them clearly less than 5 percent of the potential vote of the country, to insert a Draconian statute in the great charter of our liberties, while on every hand the man opposite is raising a glass of liquor to his lips. And there you are! We have thrown away the precious fruit of a true temperance for the hollow shell of a false abstinence. Year by year we were approaching nearer and nearer to a very practical system of temperance through the development of character. Then came this vindictive edict that no man should use wine at any time, and straightway—chaos is come again!

We forget, in this mad endeavor to control the conduct of men whose thoughts or habits differ from our own, that nations cannot be made virtuous or abstinent by acts of parliament. If laws could constrain human actions there would not today be any vice or crime or immorality in the world, yet there never was a moment when there is so much vice and crime and immorality as there is today, and in the attempt to make society virtuous by further legislative enactments we are slowly but surely destroying those liberties in striving for which our nation had its birth. I have before me now an invitation to join the National Morality League, boasting a large membership from every state in the Union, whose purpose is to follow up Prohibition with a complete stoppage of tobacco, public boxing, public dancing, and Sunday recreation, establish a restrictive censorship of the theater, moving pictures, and books, and effect the outlawing of all games for prizes, including bridge. An agent of that society—a graybearded minister, of a grim and earnest mien8—who called to ask for a contribution, informed me that they had already secured initiatory legislation in seventeen states and hoped soon to have it in final form in all of them. He told me that only that day it had been decided that he was to devote the whole of his time to the suppression of tobacco by new laws, for which he was to receive a salary of $10,000 a year. . . .

… Oliver Cromwell9 put the case for all of us when the Puritans begged him to close the public houses of England. “It is not well,” answered the great Protector, “that nine men should go thirsty because the tenth man drinks too much.”. . .

These harsh dictators have recently built up a specious and fallacious argument on the economic side which they are putting forward on every occasion. I met it last night at a dinner. We were discussing Prohibition, and I said that The North American Review had invited me to write an article on that subject. One of our most successful businessmen finished his cocktail—his second one in ten minutes—and said to me in profound earnestness: “Don’t do it. You’ll get into trouble if you do. Why, with Prohibition as we have it now, Monday morning comes and all our men are at work. In the old liquor days we could not start our works on Monday mornings. You had better not write anything—I hope you won’t.” I replied to my friend that if trouble came I was prepared to meet it with a good wallop of my own, and then challenged the accuracy of his statement about Monday morning. All the Prohibitionists say—while drinking their own glasses—that the workingmen were away on Mondays. They assume that the American workingman is naturally a drunkard. It is not true. I have been in the direction of industries as large as theirs—as large as theirs combined—and I say it is not true. A few men—six or seven—may have been missing from the big works. The same six or seven are missing now!

The short-sighted frenzy of our fanatical tormentors, who deny us good and wholesome wine and beer, is fast making us a nation of whiskey and gin drinkers. Some ministers of the Gospel, who would have been ashamed ten years ago to have liquor on their breath, take their cocktails now with the rest, and have learned to ask for their “dividends”! And when we see that it has become a national habit for boys and girls to carry flasks to their parties, and that their conduct is patterned upon the conduct of their elders, is it not high time that we should abandon the making of laws, and go back to the appeal to conscience, which after all is the basis of that righteousness which exalteth a nation?10

Prohibition is the paradise of the ostrich. With his head in the sand the stupid bird believes that what he will not see does not exist. But all around him there has been created a business worth hundreds of millions a year, which pays no tax, knows no control, is without responsibility, dispenses more or less poisoned liquors, debauches youth and age, corrupts the politicians, demoralizes the police, and spreads everywhere a contempt for all law. And the jails!—the jails which were to have been made empty are building new cells for our malefactors, because the total arrests in 100 cities in 1920 (the last year of free drink) were 950,000, while in 1924 the figure had expanded to 1,500,000. Where then are the benefits of the scheme? . . . .

The annual cost of so-called enforcement is mounting by leaps and bounds until the latest appropriation is now $30,000,000. Soon it may well be $100,000,000. The money might as well be thrown into the sea. A United States Attorney in New York declared on taking office that he had “gone on the water-wagon” and was going to padlock for a year one thousand restaurants in New York City. The inconvenience and hunger that are to be suffered by a great community when one thousand restaurants are summarily shut does not seem to give him pause. He even hinted that he had three thousand in mind. He further stated that there were now enough liquor suits pending in the New York City courts to occupy the full time of all the judges for 600 years!

The tyranny of those who would fix their standards of life upon an unwilling nation has brought with it a haunting sense of disquiet, of anxiety, of fear. There is a feeling in the most innocent heart of the shadow of hostile laws. No man—no free man—knows when he is being followed, when his habits are being watched, when some hired agent of the fanatics, anxious to disgrace him, will put the rude hand of law upon his shoulder and arrest him for some neglect or act which sustains no accusation from his own heart.

Is it not time to organize the men who love their country as a land of liberty and fight the bigoted program of these misguided moralists to a finish?

If prohibition really existed I would be for it to the end. I am myself very nearly a teetotaler. But prohibition cannot exist because it contravenes an imprescriptible right of human nature.

There are practicable and immediate ways of relief from this intolerable oppression. . . . . Congress can repeal the Volstead Act, declare that no liquor is intoxicating when not misused, and permit it to be sold in hotels and restaurants, and also in stores where it shall not be drunk on the premises. This would do away with the saloon, which is now flourishing, and would abolish the bootlegger,11 who is likewise now flourishing. . . .

Is There Prohibition? And to What Extent?

by Wayne B. Wheeler, LL.D12

General Counsel, Anti-Saloon League of America

The fact of Prohibition—the actual forbidding—is in the Constitution and the national Prohibition Act. Its success—the observance of the law by good citizens and the enforcement of the law against bad citizens, with accompanying social results—is evidently the question for discussion. . . .

Here is the situation that existed when Prohibition began to dawn and which made it imperative, and the contrasted situation today:

| Then | Now |

|---|---|

| 177,790 licensed liquor saloons, most of them selling after legal hours and to minors and drunken persons, also 100,000 speakeasies. | No licensed saloon. Speakeasies exist, as filthy and criminal as in license days. . . . |

| 1,247 breweries making 2,000,000,000 gallons of beer a year. | No breweries operating lawfully. . . . |

| 507 distilleries producing 286,085,463 tax gallons of distilled spirits in 1917. | No distilleries legally operating. . . . |

| Drinking made cheap, easy and inviting. | Drinking made costly, difficult and dangerous. |

| Alcoholic death rate of 5.8 per 100,000 yearly. … | An alcoholic death rate of 1.1 to 3.2 per 100,000 yearly. . . . |

| 1,250,000 drunkards arrested yearly, although only 20 percent of public drunkards arrested. | Over 350,000 average annual decrease in drunkenness arrests since War Prohibition, although nearly all drunkards are now arrested. . . . |

| Charity societies, Salvation Army, churches, almshouses, etc., spent millions yearly for drink-caused poverty. . . . | Decrease of 74 percent in drink caused poverty; federal census shows lowest pauperism ratio in history. . . . |

| Slums for poorly paid workers. | 51 percent of home building for workers in 1924; slums practically gone. |

| Red-light districts13 in license towns.14 | The brothel has practically vanished. |

| Venereal disease menaces national life. . . . | Venereal disease vanishing. . . . |

| Many times the amount received from liquor licenses spent to care for drink-caused crime, pauperism and insanity. | Liquor criminals through fines pay cost of own detection, prosecution and imprisonment. |

| Industrial production checked by blue Mondays,15 drink-caused accidents and inefficient drinking workers. | Industrial production speeded up, accidents lessened, efficiency increased. |

| Saloons divert over $2,000,000,000 annually from legitimate trade. | Retail trade, savings and insurance profit from saloon closing. |

| Homes wrecked and home building checked when saloon took margin of earnings between actual existence needs and total wages. | Home building increased 152 percent since Prohibition, while purchases of small homes have trebled. Building and Loan assets more than doubled in five dry years. |

That is only a sample of the catalogue one might continue, using the deadly parallel, comparing conditions since Prohibition with those before. They are a fair answer to the query: Does Prohibition prohibit? Of course, Prohibition does not completely stop the making and using of intoxicants. No prohibition law accomplishes its purpose so completely. It reduces the evil. This is the test for measuring the success of any law. There must be a measurable degree of success to have accomplished the results already secured.

Three stock arguments are offered by the brewery agents today in reply to these facts: Venality of enforcement agents; increasing arrests; drinking of youth. Formerly the control by the brewery interests threatened the life of the Republic and made necessary a Senate investigation (1918) revealing corrupt practices, unparalleled by any other group in our history. The attempted subsidization of the press, the boycotting of businessmen who favored Prohibition, the raising of a million yearly in Pennsylvania to elect wet United States senators, representatives and state legislators, the customary trade tax of three cents per gallon on beer for a slush fund for politics, was just part of the brewery policy. This same influence today is corrupting public officials, violating the law in nearly every state in the Union and opposing the passage of enforcement laws. The record is the same in kind but less in degree since Prohibition outlawed this lawless business.

Crime caused by liquor has decreased throughout the country, including crimes of violence. . . .

The total number of arrests throughout the country has increased in 1924 because of increased violation of the automobile and traffic laws and for offenses against sanitary, school and other municipal ordinances. In many communities these minor offenses number 90 percent or more of the total arrests. But they do not mean a crime wave. Sober men are less quarrelsome and less likely to be driven to crime by desperate need than drinking men.

Youth, once recruited by the hundreds of thousands by the saloon, is an occasional instead of a regular drinker. The cost and quality of post-Volsteadian drinks does not create a habit as did the licensed intoxicants. The American youth problem is less serious than that in other countries. France, the land of the vine and of the heaviest alcohol consumption, and England, the home of beer, face the same question. English boys and girls throng dance clubs at all hours of the night with flasks on their hips, doing the very things the wets say young America is doing. The daily papers, notably the London Morning Post, have been full of letters on this theme, blaming youth’s excesses on the housing situation, the movie and a host of other things, but Prohibition cannot be made the scapegoat there.

The attitude of the liquor trade toward youth is set forth in the Brewer’s Journal, of England, February 15, 1922, thus:

Yearly tens of thousands of alcoholic drinkers die. With the rising generation and whether or not they take to alcohol rests the future of the Trade commercially, politically and economically.

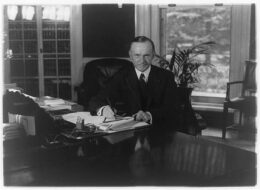

The legalized exploitation of youth has been rejected by this nation, whose attitude was clearly expressed by President [Calvin] Coolidge in his message to Congress, December 6, 1923:

There is an inescapable personal responsibility for the development of character, of industry, of thrift and self-control. These do not come from the government, but from the people themselves. But the government can and should always be expressive of the steadfast determination, always vigilant, to maintain conditions under which these virtues are most likely to develop and secure recognition and reward. This is the American policy.

It is in accordance with this principle that we have enacted laws for the protection of the public health and have adopted prohibition in narcotic drugs and intoxicating liquors.

The bootlegger and moonshiner are our inheritance from the license days. The names they bear, the illegal trade they follow, the appetites they feed, the crimes they commit, are the product of the era when the liquor interests were in power and when drinking was common instead of rare, as today. They received no more attention then, than a mosquito bite next to a carbuncle. Now they are getting the attention because the greater evil is gone. Today we are arresting and imprisoning instead of ignoring these criminals. Convictions for violations of the Prohibition law numbered 37,558 in the last fiscal year in the federal courts alone. The jail sentences imposed totaled over 3,187 years.

The cost of Prohibition enforcement is practically nominal. Fines and penalties paid into the federal treasury by convicted liquor criminals last fiscal year amounted to $6,538,115.24. The total amount expended in administering the National Prohibition Act was $7,509,146.27. . . .

Prohibition was demanded and is today supported by the overwhelming majority of the American people, who also obey these laws. A small minority, generally motivated by appetite or the desire to make money from the appetite of the liquor addict, oppose. Election returns, showing increased numbers of dry candidates elected, and the popular vote in referenda on enforcement of the law, reveal the strength of the dry public sentiment. The law is not being enforced against the American people. It is being obeyed by the American people and enforced against the un-American, the alien, the lawless and the vicious minority. That minority today prevents the decrease in crime from being even greater. . . .

Prohibition and the Younger Generation

by Cornelia James Cannon16

Whenever the older generation foregathers to discuss the younger generation tales are told to make the blood run cold. But whether youthful defiance of Prohibition adds an appreciable amount of material to the indictment is yet to be proved. . . . General adult criticism of the young must be definitely separated from a consideration of the reaction of this particular generation to the Eighteenth Amendment.

Prohibition has certainly added the charm of actual law-breaking to the primitive tang of tasting the forbidden, a temptation as old as the Garden of Eden.17 It has not thereby necessarily increased the total consumption of alcohol nor augmented the poignancy of temptation to the majority of the population, young and old.

Cheating at examinations has been ruled against since examinations were invented. But cheating has persisted, nevertheless, and at times in school and colleges, under favoring conditions, has assumed quite alarming proportions. The amount and frequency of its occurrence has borne no relation to the prohibition of the practice, since that had always existed. But it has borne a direct relation to the rigor of enforcement. Where supervision has been lax, cheating in some schools has become so common that a student who went into an examination with white cuffs ran risk of being considered a moral prude. Where the proctoring has been competent, the technique of cheating has become one of the lost arts, symbolic of a decadent or a weakling schoolroom civilization. . . .

The question is not whether youth breaks and defies the laws, but whether conditions as regards drinking of alcohol under Prohibition are worse than they were before the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect. . . .

A man, closely associated for sixty years with one of our large universities, first as student and then as trustee, finds the young men of the present generation incomparably superior to earlier generations in their whole attitude toward alcohol. In his days at college there was never a morning when the college yard did not show one or two students under the influence of alcohol, whose condition was unreprobated18 by their contemporaries. Students get drunk today, but the proportion is by comparison negligible. In addition with a new seriousness and wholesomeness the modern student body is developing an interest in other forms of pleasure which are destined in time to swing the rebels and weaklings into line. When youth itself voices distaste, the tide has turned, and here and there, throughout our educational institutions, the word, not of criticism, but of disgust for the carrier of the flask, is beginning to be heard.

The generation of children growing up, who have never seen a saloon, to whom the once common sight of the Saturday night bacchanalian orgie19 near the drinking resorts is not the ordinary tolerated incident of the week, is the generation most profoundly affected by Prohibition. These children are coming to maturity in a world becoming emancipated from the degradations and vulgarities which are inevitably associated with free access to alcohol. The flaunting defiance of the law against alcohol in our large cities cannot be dissociated from the defiance of all other law in those crowded, inchoate centers, and should not blind us to the decencies and conformities in our smaller communities where the Eighteenth Amendment brings additional strength to an enforcing public opinion.

There is a suspicion in many minds that the abuse of alcohol has passed from a lower to a higher stratum of society, and that it is the educated, privileged groups among the young on whom Prohibition is working a deleterious effect. In a measure this cannot fail to be true, not necessarily because the so-called higher stratum is more lawless and the lower less, but because the group with the largest funds can most effectively defy the law. In so far as higher and lower are measures of income, it is safe to say that the worst lawbreakers of this kind among the young are those with the most elastic pocketbooks.

As far as the young women are concerned there are certainly groups, both among girls who are brought into juvenile courts and those who are expelled from college, who are using alcohol as the same type of girl did not do a generation ago. But is this due to the existence of the Eighteenth Amendment, or to the extraordinary extension of opportunity open to the young women of today?

The girl of this decade is being brought before the bar of public disapproval by the horrified adult, and is making out a pretty good case against her prosecutor.

She says in effect, “You are letting me undertake work never before done by women. You are allowing me to be exposed at an early age to conditions and temptations to which women have never been subjected in the history of the world. I am in factories, stores, offices in the day time, and in theaters, at public dance halls, and on the streets at night, with no protection save such as society affords to all its members. You allow me to return to my home from my work or my play at all hours of the twenty-four unguarded. I am fending for myself in a world strange and alluring to me. I try all things, good and bad alike. You do not take responsibility for me. I will take it for myself, and you shall not blame me for the disasters I bring upon you or myself.”

What, after all, has the older generation done save abdicate its position of authority and obligation toward the younger generation in relation to Prohibition as in relation to everything else? In so far as Prohibition has failed to do for the young what was hoped of it, the blame rests with the older generation. If we leave gunpowder around, can we punish children for blowing off their fingers? If we ourselves fail to have conviction enough to impress our standards upon our boys and girls, shall we hold them guilty?

The whole question of the effect of Prohibition upon the young is a question as to how adequately we safeguard and protect our children. Can we deny that we have largely left them to find their way in the wilderness of temptation we have allowed to grow up about them? . . .

Our hope lies in the honestly of the younger generation and the clearsightedness with which they watch our blundering and our fumbling. They will never allow their children to do the things we have allowed them to do, and, from the bitter knowledge gained through our weakness and indecision, will be able to throw round the next generation a protection which we have failed to give them.

- 1. James P. Holland (1865–1941) belonged to the Eccentric Firemen’s Union and served as president of the New York State Federation of Labor from 1916 to 1926.

- 2. Sumptuary laws regulate personal purchases (food, drink, clothes) considered extravagant or harmful.

- 3. A lessee is someone who holds a lease.

- 4. The Anti-Saloon League (founded in 1893) and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (founded in 1874) led the campaign for a national prohibition amendment. Their strategy entailed legislative lobbying, a massive propaganda campaign, and organizing local chapters.

- 5. The American Federation of Labor (founded in 1886) was an association of craft-based trade unions whose members were mostly skilled, white, male workers.

- 6. “Local option” referred to localities passing laws that restricted or prohibited alcohol production, distribution, or consumption. Local option laws resulted in half the country going dry before the Eighteenth Amendment was ratified, and kept many areas dry after the Twenty-first Amendment (1933) ended Prohibition.

- 7. Samuel Harden Church (1858–1931) was president of the Carnegie Institute (founded by industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie), which operated a library, art gallery, concert hall, and natural history museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

- 8. One’s bearing or demeanor.

- 9. In the English Civil War (1642–1651), Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658) led the rebellion against the monarchy that established a Puritan commonwealth. He subsequently ruled Britain as Lord Protector until his death. Cromwell was a moderate Puritan who purged the Church of England of religious practices deemed too Catholic, but he also tolerated other religions and was known to smoke, drink, and dance in moderation.

- 10. Proverbs 14:34.

- 11. A bootlegger made and/or sold alcohol illegally.

- 12. Wayne B. Wheeler (1869–1927) became head of the Anti-Saloon League in 1902, and steadfastly refused to support any redefinition of what constituted an intoxicating beverage once the Eighteenth Amendment was adopted.

- 13. Red-light districts contained high concentrations of sex workers and/or houses of prostitution (also known as brothels).

- 14. License towns were places where local governments issued licenses to sell alcohol.

- 15. Blue Mondays referred to depressed, hungover workers returning to work after drinking heavily over the weekend.

- 16. Cornelia James Cannon (1876–1969) was a novelist and progressive reformer who published essays on a variety of topics, including women’s rights, public education, corruption in city government, immigration policy, and eugenics.

- 17. In the Christian Old Testament Book of Genesis, God banished Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden when they succumbed to temptation and ate forbidden fruit, creating the doctrine of original sin.

- 18. Not condemned or criticized.

- 19. A party where guests indulge in excessive alcohol consumption and wild behavior.

Annual Message to Congress (1925)

December 08, 1925

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.