Introduction

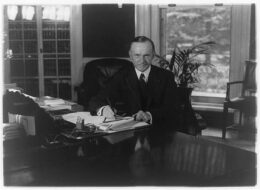

After the Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles, the United States sought other ways to promote peace and disarmament. In 1921–1922 President Warren G. Harding successfully negotiated a series of naval disarmament treaties. President Calvin Coolidge (1872–1933) attempted to further curtail the naval arms race with additional limitations on naval capacities, but the Geneva Naval Conference of 1927 ended without an international agreement.

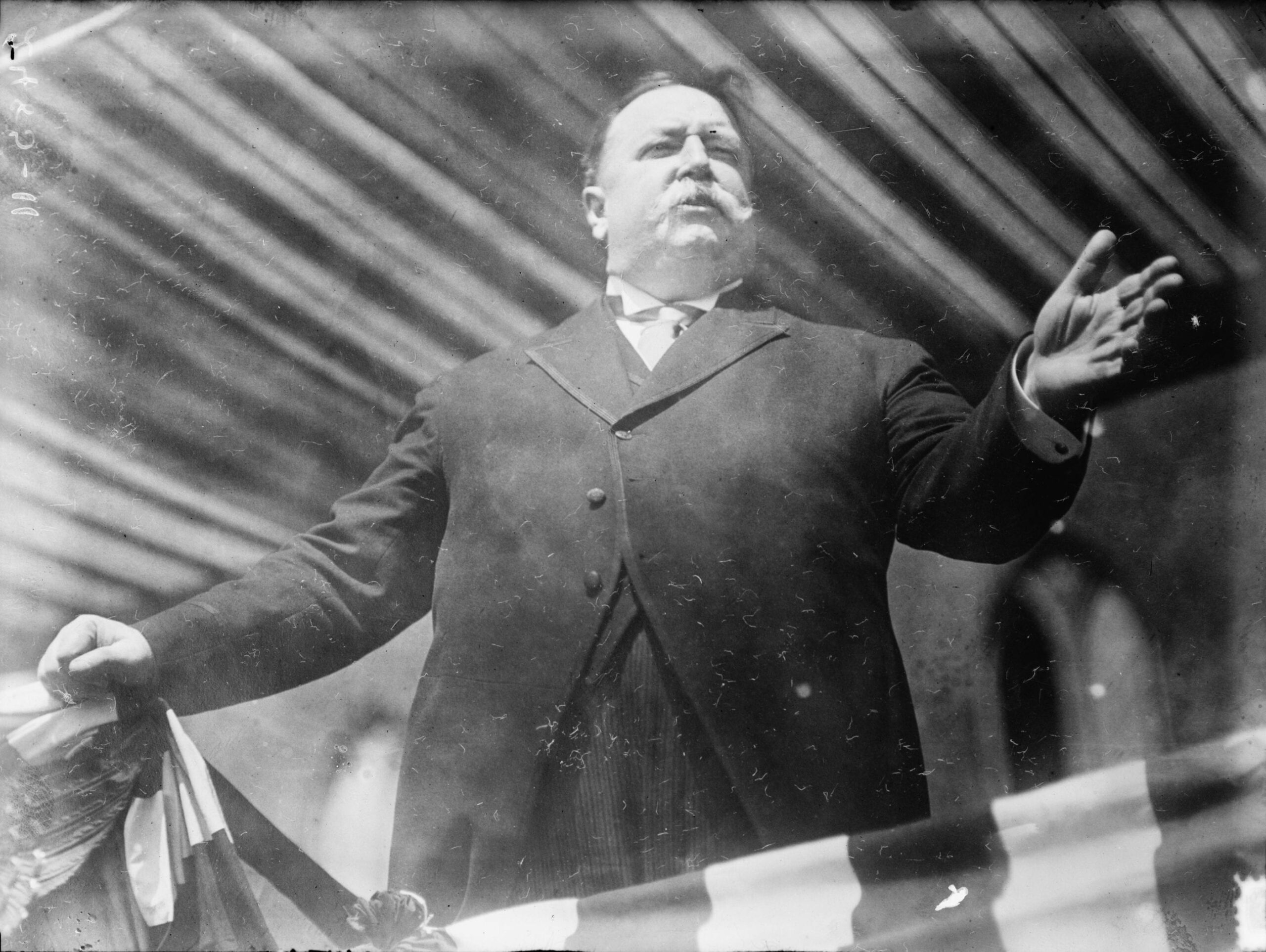

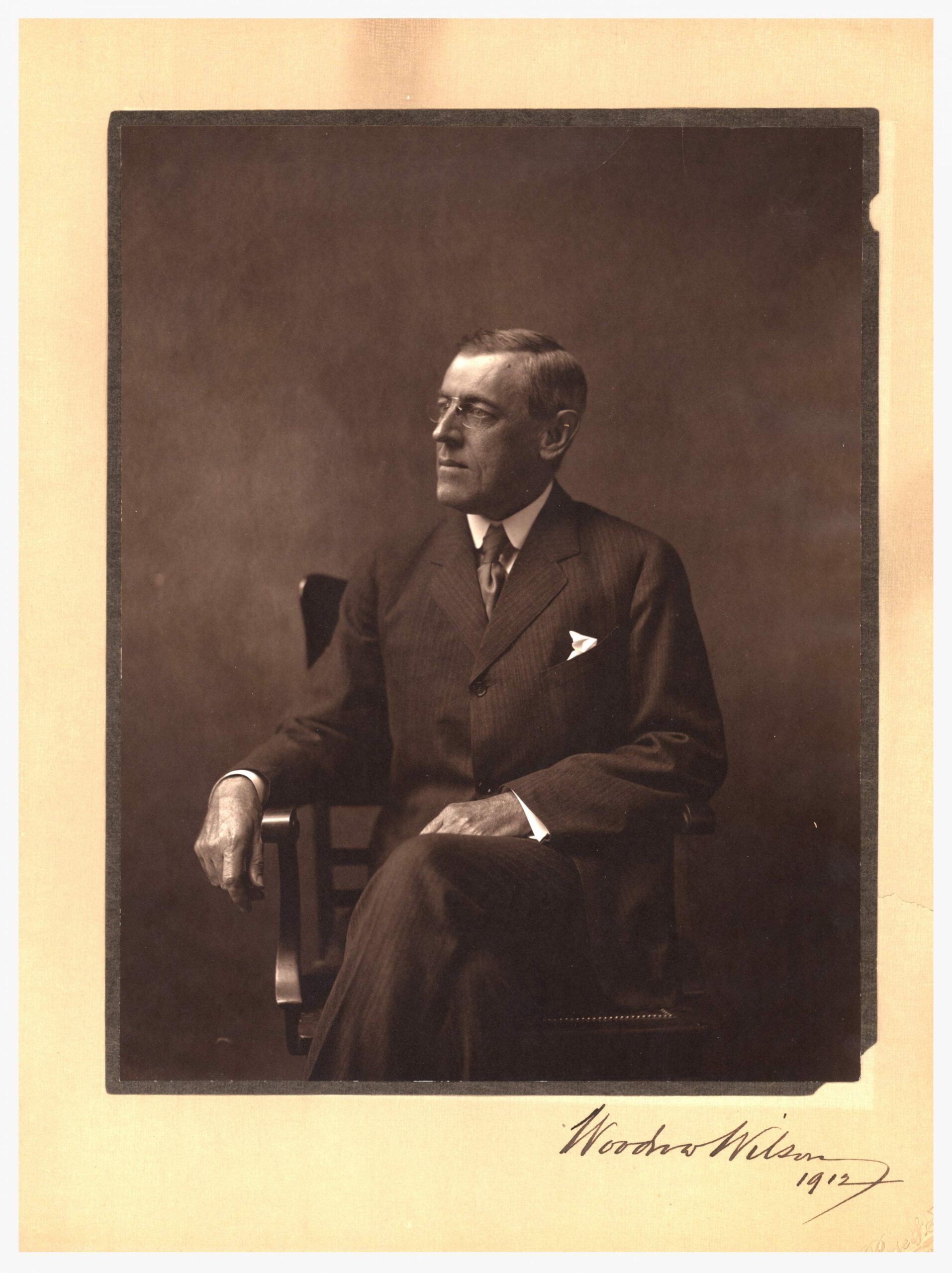

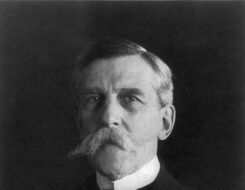

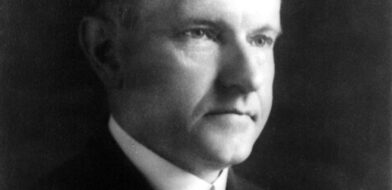

That same year, Coolidge accepted an invitation from the French government to discuss the possibility of outlawing war between the United States and France. Coolidge’s secretary of state, Frank B. Kellogg (1856–1937), quickly decided to include other nations in the negotiations to avoid the impression that the United States was formally allying with France. The result was the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact, a multilateral nonaggression treaty that was eventually signed by sixty-eight nations, including Germany and Japan. In 1929 Kellogg received the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on the pact.

The excerpts below come from a speech Kellogg delivered in June 1928 to help publicize and explain the pact, which was officially signed in August. Signatories renounced aggressive war as an instrument of national policy and agreed to use peaceful means to resolve conflicts. The treaty allowed for wars of self-defense, which critics claimed made the agreement useless. The lack of an enforcement mechanism also drew complaints. Supporters, however, viewed the Kellogg-Briand Pact as an important milestone in international law—the first international agreement to state that it was unlawful to use force to acquire territory. In war crimes trials after World War II, German and Japanese officials were convicted of committing crimes against peace, and thereby violating the Kellogg-Briand Pact (one of numerous charges and convictions).

—Jennifer D. Keene

Frank B. Kellogg, “Address of the Honorable Frank B. Kellogg, Secretary of State,” June 11, 1928, in U.S. Department of State, The General Pact for the Renunciation of War: Text of the Pact as Signed. Notes and Other Papers (Washington, DC: GPO, 1928), 69–71. Available at https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_General_Pact_for_the_Renunciation_of/micmAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

. . .It is known to all of you that in June 1927 M. [Aristide] Briand, the French minister of foreign affairs, made a historic proposal to the United States.1 He suggested that our two countries conclude a treaty condemning war and renouncing it as an instrument of national policy in their mutual relations. That proposal was carefully considered by the United States, and the more it was examined, the more we were convinced that to realize its greatest usefulness M. Briand’s inspiring idea should be enlarged so as to make it possible to bring within the scope of such a treaty not only France and the United States, but also all the other nations of the world. The French government was informed of our views and for several months we exchanged notes with France on this general subject. Finally on April 13, 1928, the United States with the full approval of France transmitted for the consideration of the British, German, Italian, and Japanese governments the texts of the diplomatic notes previously exchanged by the two governments. At the same time the United States submitted to those governments on its own initiative a preliminary draft of a treaty for the renunciation of war, representing in a general way the form of treaty which it was prepared to sign. The four governments addressed were asked whether they were in a position to conclude such a treaty.

Encouraging replies have now been received from them all. They have all expressed cordial approval of the principle underlying the proposal of the United States, and have indicated a sincere desire to collaborate in the conclusion of an appropriate treaty for the renunciation of war. . . .The force of public opinion in this country and abroad has already made itself felt. The peoples of the world seem unquestionably to want their governments to renounce war in the most effective way possible.

The antiwar treaty which the United States has proposed, and which as I have said has its origin in the suggestions made by M. Briand a year ago, is simple and straightforward. That grand conception of the French foreign secretary undoubtedly had its inspiration in the deep-seated desire of the French people, as well as all the people of Europe, to avoid another great cataclysm of war. It is significant that Europe since the Great War has been engaged in efforts of various kinds to assuage national and racial animosities, to settle international disputes, and to prevent war. What I believe, and I am convinced that the leaders of the governments believe, is that there should be one more step in this effort, and that is, a simple declaration against war as an institution for the settlement of international controversies. Since this discussion commenced between France and the United States, the idea has appealed with increasing force to the public opinion of the world. As one looks back over the history of the four years of that unparalleled carnage, which left its trail of desolation and death, one cannot believe that the nations will hesitate to commit themselves in the most unqualified and solemn terms to the renunciation of recourse to war.

There are, of course, cynical individuals who decry all efforts to lessen the likelihood of war and belittle in particular the present negotiations. There are others who believe in war as an institution and whose support, if any, will be cold and grudging. But I am convinced that those of us who believe wholeheartedly in this movement are no less realistic. We know that the peoples of the world desire peace and dread any new international conflict. We know that the peoples of the world are becoming more and more articulate and that governments are becoming more and more responsive to their wishes. We now find peoples and governments united in a common and sincere desire to prevent so far as possible the outbreak of any war anywhere and seriously considering the best form of multilateral treaty to give effect to their aspirations. It is a most impressive manifestation of the spiritual nature of man.

With the passage of time the emphasis in our present negotiations is being placed not on narrow technical considerations of a legalistic nature, but on the broad principles underlying the entire idea. It is peace, not war, that we are seeking to perpetuate, and I am firmly convinced that the simple, straightforward, unequivocal declaration against war which the United States borrowed from M. Briand and incorporated in its draft treaty is the one that has the greatest moral value and the one that will in the long run commend itself to all the peoples concerned. It has no hidden meaning. It is easily understood. . . .In these circumstances is it too much to hope that all may find themselves in the near future able to sign with the United States a treaty under which we all declare in the names of our respective peoples that we condemn recourse to war for the solution of international controversies and renounce it as an instrument of national policy in our relations with one another, and agree that the settlement or solution of all disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among us, shall never be sought except by pacific means? I do not think that it is too much to hope that such a treaty will be signed. . . .