No related resources

Introduction

Jessie Fauset (1882–1961) played a pivotal role in the Harlem Renaissance. A notable author in her own right, she used her position as literary editor of The Crisis to nurture the early careers of future luminaries, including Langston Hughes (1902–1967). Fauset was born in Philadelphia and studied languages at Cornell University. Before joining The Crisis in 1919 she taught at the M Street High School in Washington, DC. Bucking the traditional tendency to offer only vocational instruction to Black students, the M Street High School taught a classical curriculum to nurture educated Black leaders who could advance the race (the so-called Talented Tenth).

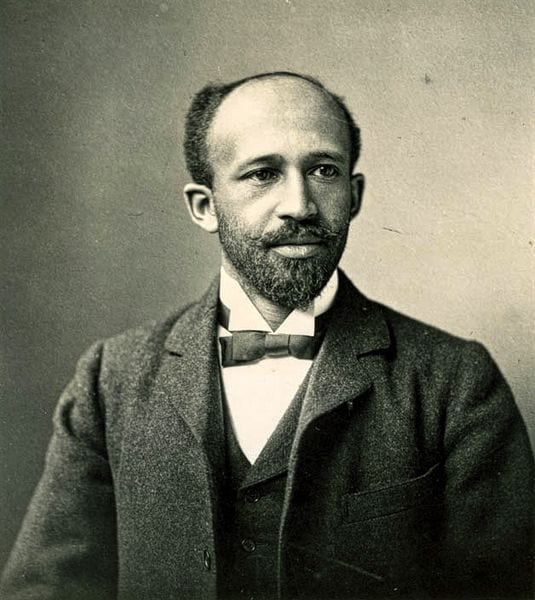

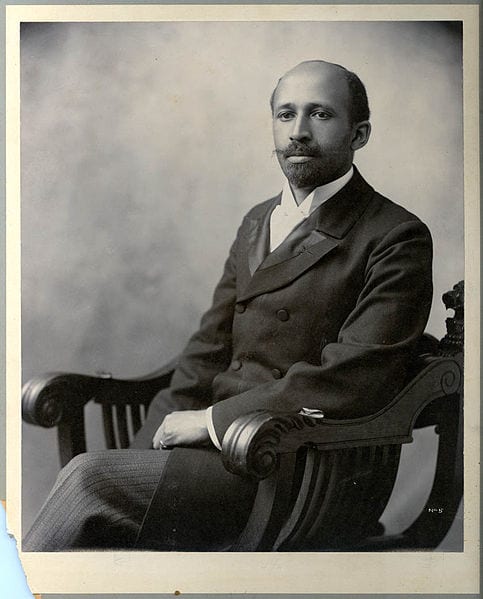

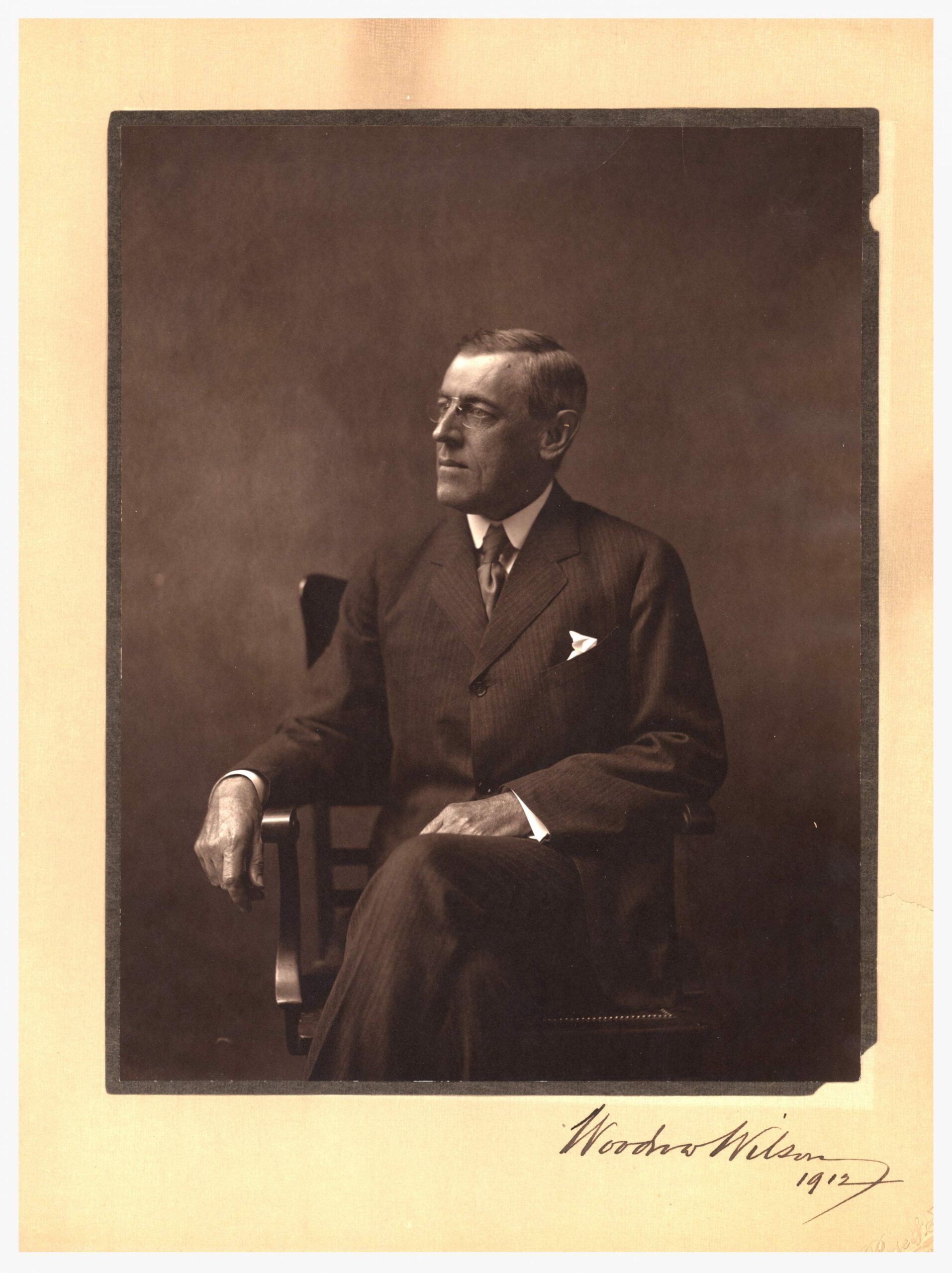

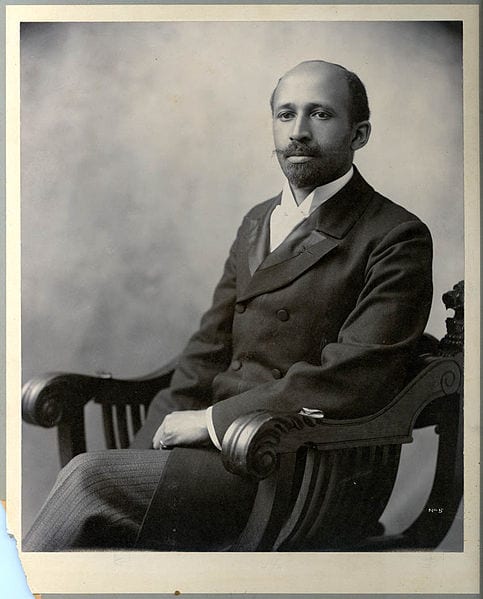

Her status as a member of the Talented Tenth did not insulate Fauset from racial discrimination. In this 1922 essay, Fauset explored how racial prejudice and the fraught nature of American race relations impacted her daily life. “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others,” wrote civil rights activist and scholar W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) in The Souls of Black Folks (1903). Fauset gave voice to the meaning of Du Bois’s statement for Black women.

Jessie Fauset, “Some Notes on Color,” The World Tomorrow (March 1922), 76–77. Available at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.ah6h7m&view=1up&seq=82.

A distinguished novelist said to me not long ago: “I think you colored people1 make a great mistake in dragging the race problem into your books and novels. It isn’t art.”

“But good heavens,” I told him, “it’s life, it’s colored life. Being colored is being a problem.”. . .

. . .[A]lways the inference is implied that we live objectively with one eye on the attitude of the white world as though it were the audience and we the players whose hope and design is to please.

Of course we do think about the white world, we have to. But not at all in the sense in which that white world thinks it. For the curious thing about white people is that they expect us to judge them by their statute-books and not by their actions. But we colored people have learned better, so much so that when we prepare for a journey, when we enter on a new undertaking, when we decide on where to go to school, if we want to shop, to move, to go to the theater, to eat (outside of our own houses) we think quite consciously, “If we can pull it through without some white person interfering.”

I have hesitated more than once about writing this article because my life has been spent in the localities which are considered favorable to colored people and in the class which least meets the grossest forms of prejudice. And yet—I do not say I would if I could—but I must say I cannot if I will forget the fact of color in almost everything I do or say in the sense in which I forget the shape of my face or the size of my hands and feet.

Being colored in America at any rate means: Facing the ordinary difficulties of life, getting education, work, in fine getting a living plus fighting every day against some inhibition of natural liberties.

Let me see if I can give you some idea. I am a colored woman, neither white nor black, neither pretty nor ugly, neither specially graceful nor at all deformed. I am fairly well educated, of fair manners and deportment. In brief, the average American done over in brown. In the morning I go to work by means of the subway, which is crowded. Presently somebody gets up. The man standing in front of the vacant place looks around meaning to point it out to a woman. I am the nearest one, “But oh,” says his glance, “you’re colored. I’m not expected to give it to you.” And down he plumps. According to my reflexes that morning, I think to myself “hypocrite” or “pig.” And make a conscious effort to shake the unpleasantness of it off, for I don’t want my day spoiled.

At noon I go for lunch. But I always go to the same place because I am not sure of my reception in other places. If I go to another place I must fight it through. But usually I am hungry. I want food, not a lawsuit. And, too, how long am I to wait before I am sure of the slight? Shall I march up to the proprietor and say, “Do you serve colored people?” or shall I sit and drum on the table for fifteen or twenty minutes, feel my anger rising, prepare to explode only to have the attendant come at that moment and nonchalantly arrange the table? I eat but I go out still not knowing whether the delay was intentional or not. The white patron would be annoyed at the delay. I am, too, but ought I to be annoyed at something in addition to that? I can’t tell. The uncertainty beclouds my afternoon.

An acquaintance—a white woman—phones me that she can accept a long-standing invitation of mine for luncheon. We meet and I suggest my old standby. “Let’s go somewhere else,” she urges. “I don’t like that place.”

Ruefully but frankly I stammer, “Well you see—I’m not quite sure—that is—”

“Oh, yes,” she rejoins in quick pity. “I forgot that. I’m so sorry.”

But I hate to be pitied even so sincerely. I hate to have this position thrust upon me.

All of us are passionately interested in the education of our children, our younger brothers and sisters. And just as deliberately, as earnestly as white people discuss tuition, relative ability of professors, expenses, etc., so we in addition discuss the question of prejudice. “Of course he’ll meet some. But would they let it interfere with his deserts? I don’t know. I guess I’d better send him to A instead of B. They don’t cater as much to the South as at B.”

I think the thing that irks us most is the teasing uncertainty of it all. Did the man at the box-office give us the seat behind the post on purpose? Is the shop-girl impudent or merely nervous? Had the position really been filled before we applied for it? What actuates the teacher who tells Alice—oh, so kindly—that the college preparatory course is really very difficult. Even remarkably clever pupils have been known to fail. Now if she were Alice—

Other things cut deeper, undermine the very roots of our belief in mankind. In school we sing “America,” we learn the Declaration of Independence, we read and even memorize some of the passages in the Constitution. Chivalry, kindness, consideration are the ideals held up before us—

Honor and faith and good intent,

But it wasn’t at all what the lady meant.2

the lady in this case being the white world. The good things of life, the true, the beautiful, the just, these are not meant for us.

So much is this difference impressed on us, “this for you but that quite other thing for me,” that finally we come to take all expressions of a white man’s justice with a cynical disbelief, our standard of measure being a provident “How does he stand on the color question?”

I am constantly amazed as I grow older at the network of misunderstanding—to speak mildly—at the misrepresentation of things as they really are which is so persistently cast around us. Sometimes it is by implication, sometimes by open statement. Thus we grow up thinking that there are no colored heroes. The foreign student does hear of Garibaldi, of Cromwell, of Napoleon, of Marco Bozzaris.3 But neither he nor we hear of Crispus Attucks.4 There are no pictures of colored fairies in the storybooks or even of colored boys and girls. “Sweetness and light” are of the white world.

Native Africans are “savages” owing their little knowledge of civilization to the kindly European traveler who is represented as half philanthropist, half savant. How much do we learn of indigenous African art, culture, morals? We are told of the horrors of polygamy without a word of the accompanying fact that prostitution in Africa was comparatively unknown—until the whites introduced it.

We are given the impression that we are the last in the scale of all races, that even other dark peoples will have none of us.5 I shall never forget how astonished I was to see in London at the second Pan-African Congress6 the very real willingness of Hindu leaders to cast in their lot with ours.

More serious still, we are constantly being confronted with a choice between expediency and an intellectual dishonesty, intangible, indefinable and yet sometimes I think the greatest danger of all. If persisted in it is bound to touch the very core of our racial naturalness. And that is the tendency of the white world to judge us always at our worst and our own realization of that fact. The result is a stilted art and a lack of frank expression on our part. We find “The Emperor Jones” wonderful, but why couldn’t O’Neill have portrayed a colored gentleman?7 We wish he had. “Batouala”8 is a marvelous piece of artistry, but we are half glad it is written in French so that the average white American won’t insist that here is the true African prototype.

Someone will say: “These are trifles.” What have I to complain of as compared with the condition of Negroes in South Africa, in Georgia, in the Portuguese possessions? I do not have to fear lynching, or burning, or dispossession.

No, only the reflex of those things. Perhaps it is mere nervousness, perhaps it is something more justifiable. Often when I am sitting in a crowded assembly I think, “I wish I had taken a seat near the door. If there should be an accident, a fire, none of these men around here would help me.” Place aux dames9 was not meant for colored women.

I have not been dispossessed, but I have had to leave Philadelphia—the city of my birth and preference, because I was educated to do high school work and it was impossible for a colored woman to get that kind of work in that town. So I, too, have assisted in the Negro Exodus which the student of Sociology considers in class-room and seminary.

And so the puzzling, tangling, nerve-wracking consciousness of color envelops and swathes us. Some of us, it smothers.

- 1. In the first part of the twentieth century, “colored” and “Negro” were considered polite terms to use when referencing African Americans, part of an effort to eradicate common usage of the n-word. The legacy of these terms persists in the names of premier civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (founded in 1910) and the United Negro College Fund (founded in 1944). Since the 1960s “Black,” “African American,” and more recently “people of color” have become the preferred terms of usage in American society.

- 2. Fauset was quoting from a poem by Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936), “The Vampire.”

- 3. Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882) was an Italian general whose military victories led to the creation of a unified Italy in 1861. In the English Civil War (1642–1651), Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658) led the rebellion against the monarchy that established a Puritan commonwealth. Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) was a French military general and statesman who modernized France and during the Napoleonic Wars (1801–1815) temporarily conquered most of Europe. General Marco Bozzaris (in Greek, Markos Botsaris, 1788–1823) was a key leader during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1832) against the Ottoman Empire.

- 4. Crispus Attucks (1723–1770), a sailor of African and Native American descent, was shot and killed during the Boston Massacre, the first American to die in the American Revolution. He became an icon of the antislavery movement in the nineteenth century.

- 5. Popular pseudoscientific racial theories created hierarchical rankings based on the supposed innate traits and abilities of different racial and ethnic groups. These rankings usually placed American-born Caucasians at the top, followed by Northern Europeans, Southern Europeans, and Asians, with people of African descent at the very bottom.

- 6. The Second Pan-African Congress in 1921 (which held meetings in London, Brussels, and France) brought together delegates from the United States, Africa, Europe, and European colonial possessions to discuss collective international solutions to end racial discrimination and colonial rule.

- 7. The Emperor Jones by white playwright Eugene O’Neill (1888–1953) was a box-office hit in 1920. The play involves a working-class African American man who, after committing a murder, flees to a Caribbean island where he exploits the ignorance and superstitions of the local residents to become emperor. Eventually his subjects rebel and he escapes into the jungle.

- 8. Batouala (1921), by René Maran, recounts the life of an African chieftain who battles another man for the affections of one of his nine wives. The book, which openly criticizes French colonialism, won the Prix Goncourt, France’s highest literary honor, making Martinique native Maran the first Black author to receive the award.

- 9. Place aux dames is a French phrase meaning “ladies first.”

Henry Ford’s Five-Day Week

April 29, 1922

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.