The success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955–56 brought increased energy and attention to the civil rights movement, and the question naturally arose how to build on that success. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and like-minded fellow ministers founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, intending to organize a regional campaign for voting rights. That campaign initially struggled to gain momentum, and younger activists soon undertook a more daring form of direct-action protest.

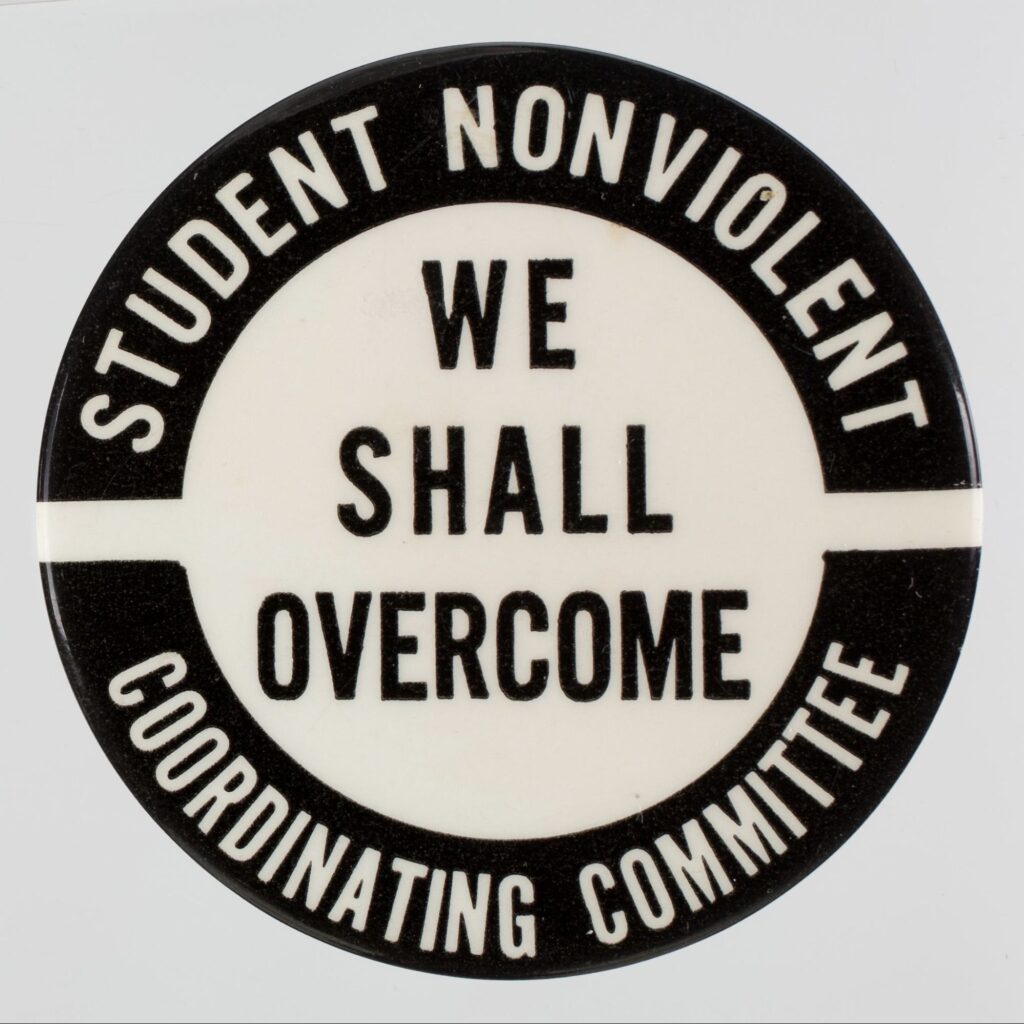

On February 1, 1960, four students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College staged a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. They remained at the counter until closing time and returned the next day; within a week more than one thousand students had joined the Woolworth’s lunch counter protest. The students’ sit-in movement spread rapidly across the South. In April that same year, as the sit-ins continued, SCLC director Ella Baker (1903–1986) organized a meeting of student protesters in Raleigh, North Carolina. The result of that meeting was the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

SNCC quickly took its place among the major civil rights organizations of the 1960s, conducting not only sit-ins but also a further round of Freedom Rides and participating in the March on Washington. The present selection is the organization’s founding statement.

—Peter C. Myers