Introduction

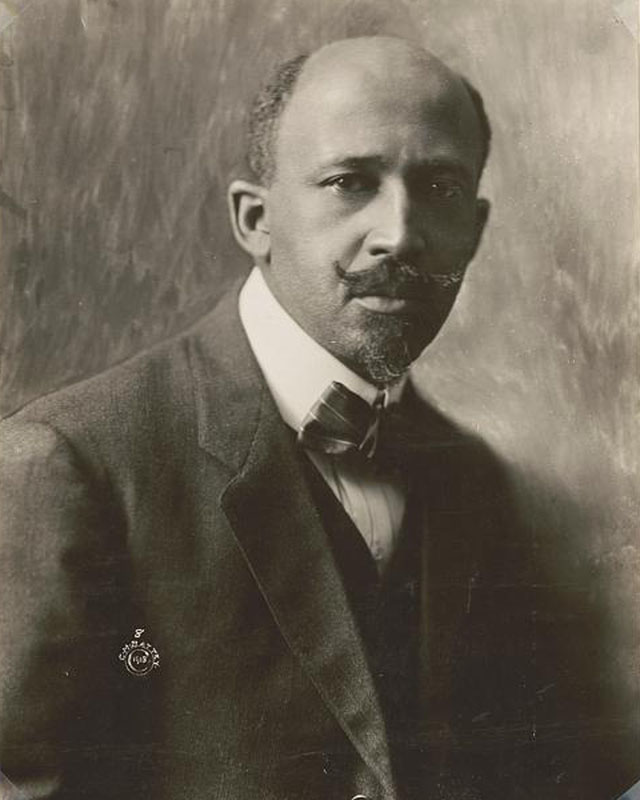

W.E.B. Du Bois was a prominent African American thinker and author during the first half of the 20th century. He was the first African American to receive a PhD, and his book, The Souls of Black Folk, has become a literary classic. Du Bois co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1910 and served twenty-four years as the first editor of its official magazine, The Crisis. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Du Bois engaged in a political battle with another prominent African American leader, Booker T. Washington, architect of the so-called Atlanta Compromise. Washington argued that political progress for blacks in the United States would come when blacks established a cooperative economic partnership with whites and argued that social equality could not be imposed on people of different races. Du Bois opposed racial segregation and disenfranchisement and insisted on full civil and political rights for African Americans without delay.

In the March 1928 edition of The Crisis, Du Bois responded to a letter from Roland Bennett, then a high school sophomore. Bennett had objected to the word “Negro” being used to identify native Africans in a recent issue of the magazine. He argued that “Negro” and “N_____” were “white man’s words” meant to stamp black people with a badge of inferiority. He recommended the magazine substitute “native” or “Africans” for Negro(es). Du Bois admonished the youngster. “Do not at the outset of your career make the all too common error of mistaking names for things,” he wrote. “Names are only conventional signs for identifying things. Things are the reality that counts.” Names are conventions adopted by people only after continued use to describe a group. British, Du Bois argued, was no more a historically accurate name for people of the United Kingdom than Negro. Both were linguistic habits and shorthand for written and oral conversation. In his response, Du Bois challenged young Roland to consider whether a change in name would solve the problem of racial prejudice, discrimination, and injustice.

Please be aware that this historical document contains offensive language and ideas.

—Ray Tyler

"Postscript, by W.E.B. Du Bois. The Crisis (March 1928), pg. 96. https://ia801803.us.archive.org/28/items/sim_crisis_1928-03_35_3/sim_crisis_1928-03_35_3.pdf

Dear Sir:

I am only a high school student in my Sophomore year, and have not the understanding of you college educated men. It seems to me that since THE CRISIS is the Official Organ of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People which stand for equality for all Americans, why would it designate and segregate us as "Negroes," and not as "Americans."

The most piercing thing that hurts me in this February CRISIS, which forced me to write, was the notice that called the natives of Africa, "Negroes," instead of calling them "Africans," or "natives."

The word "Negro," or "nigger," is a white man's word to make us feel inferior. I hope to be a worker for my race, that is why I wrote this letter. I hope that by the time I become a man, that this word, "Negro," will be abolished.

Roland A. Barton

My dear Roland:

Do not at the outset of your career make the all too common error of mistaking names for things. Names are only conventional signs for identifying things. Things are the reality that counts. If a thing is despised, either because of ignorance or because it is despicable, you will not alter matters by changing its name. If men despise Negroes, they will not despise them less if Negroes are called "colored" or "Afro-Americans."

Moreover, you cannot change the name of a thing at will. Names are not merely matters of thought and reason; they are growths and habits. As long as the majority of men mean black and brown folk when they say "Negro," so long will Negro be the name of folks brown and black. And neither anger nor wailing nor tears can or will change the name until the name-habit changes.

But why seek to change the name? "Negro" is a fine word. Etymologically and phonetically it is much better and more logical than "African" or "colored" or any of the various hyphenated circumlocutions. Of course, it is not "historically" accurate. No name ever was more historically accurate: neither "English," "French," "German," "White," "Jew," Nordic" nor "Anglo-Saxon." They were all at first nicknames, misnomers, accidents, grown eventually to conventional habits and achieving accuracy because, and simply because, wide and continued usage rendered them accurate. In this sense, "Negro" is quite as accurate, quite as old and quite as definite as any name of any great group of people.

Suppose now we could change the name. Suppose we arose tomorrow morning and lo! Instead of being "Negroes," all the world called us "Cheiropolidi,"—do you really think this would make a vast and momentous difference to you and to me? Would the Negro problem be suddenly and eternally settled? Would you be any less ashamed of being descended from a black man, or would your schoolmates fell any less superior to you? The feeling of inferiority is in you, not in any name. The name merely evokes what is already there. Exorcise the hateful complex and no name can ever make you hang your head.

Or, on the other hand, suppose that we slip out of the whole thing by calling ourselves "Americans." But in that case, what word shall we use when we want to talk about those descendants of dark slaves who are largely excluded still from full American citizenship and from complete social privilege with the white folk? Here is Something that we want to talk about; that we do talk about; that we Negroes could not live without talking about. In that case, we need a name for it, do we not? In order to talk logically and easily and be understood. If you do not believe in the necessity of such a name, watch the antics of a colored newspaper which has determined in a fit of New Year's Resolutions not to use the word "Negro"!

And then too, without the word that mans Us, where are all those whose spiritual ideals, those inner bonds, those group ideals and forward strivings of this might army of 12 millions? Shall we abolish there with the abolition of a name? Do we want to abolish them? Of course we do not. They are our most precious heritage.

Historically, of course, your dislike of the word Negro is easily explained: "Negroes" among your grandfathers meant black folk; "Colored" people were mulattoes. The mulattoes hated and despised the blacks and were insulted if called "Negroes." But we are not insulted—not you and I. We are quite as proud of our black ancestors as of our white. And perhaps a little prouder. What hurts us is the mere memory that any man of Negro descent was ever so cowardly as to despise any part of his own blood.

Your real work, my dear young man, does not lie with names. It is not a matter of changing them, losing them, or forgetting them. Names are nothing but little guideposts along the Way. The Way would be there and just be as hard and just as long if there were no guideposts,—but not quite as easily followed! Your real work as a Negro lies in two directions: First, to let the world know what there is fine and genuine about the Negro race. And secondly, to see that there is nothing about that race which is worth contempt; your contempt, my contempt; or the contempt of the wide, wide world.

Get this then, Roland, and get it straight even if it pierces your soul: a Negro by any other name would be just as black and just as white; just as ashamed of himself and just as shamed by others, as today. It is not the name—it's the Thing that counts. Come on, Kid, let's go get the Thing!