No study questions

No related resources

Introduction

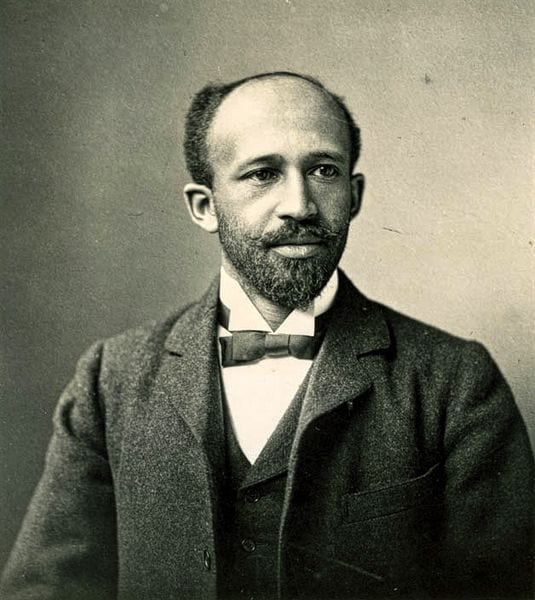

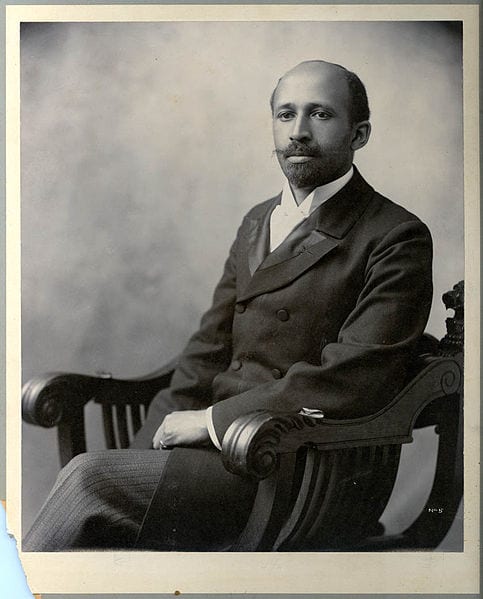

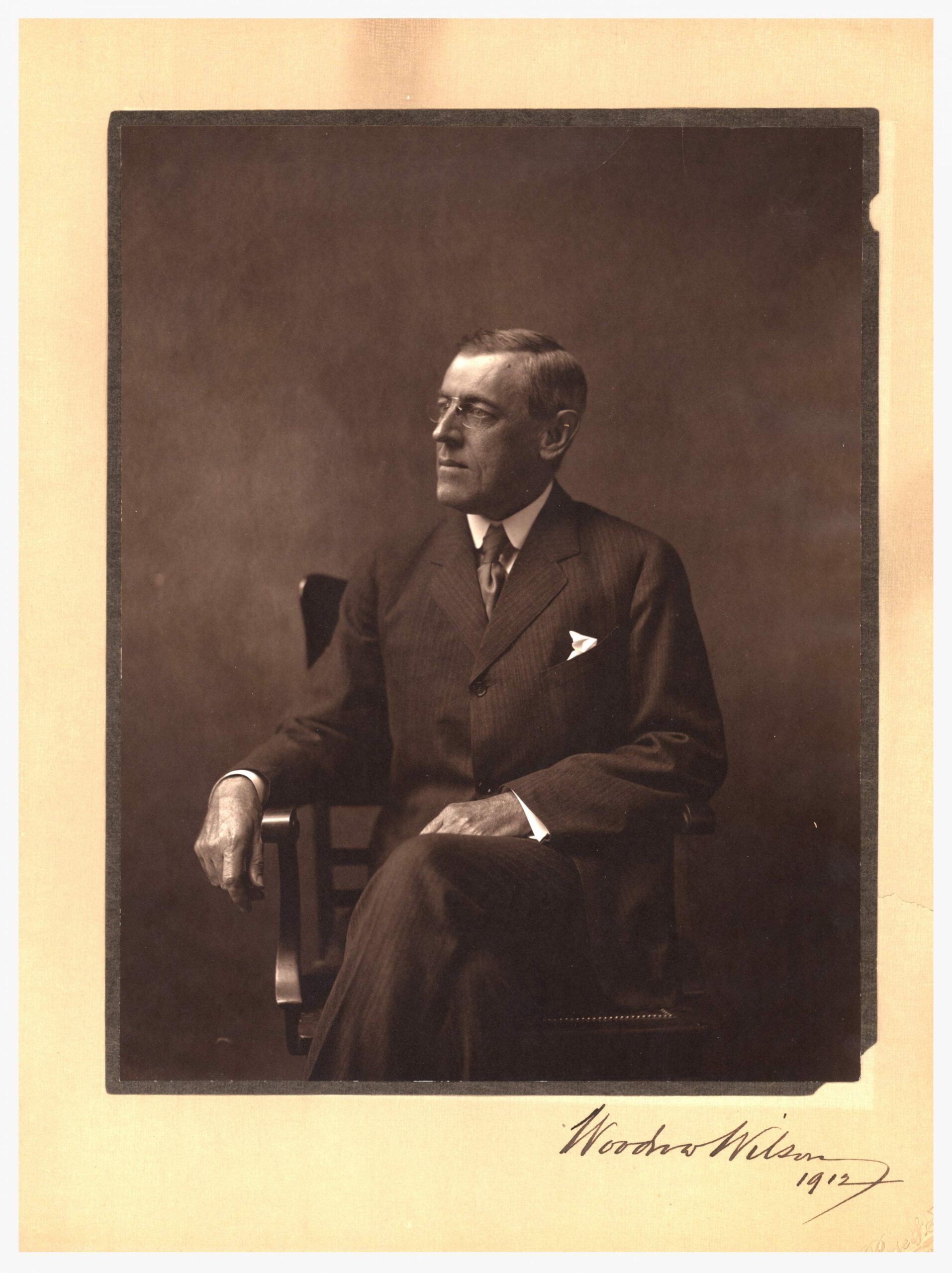

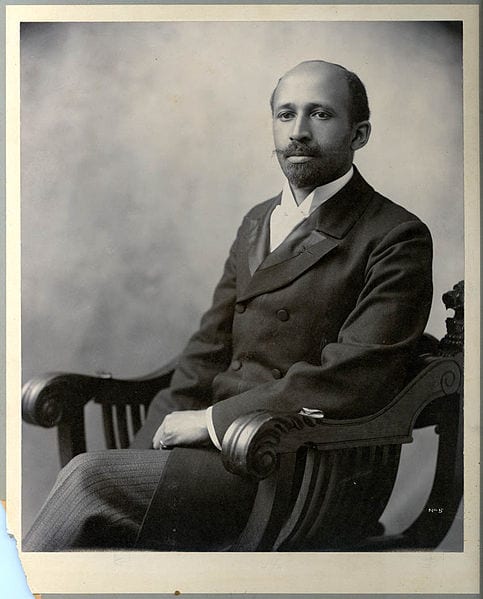

For about 30 years, from around 1900 to the late 1920s, America had an active and popular eugenics movement. Supporters of eugenics argued the public good required removing from the population genes thought to cause low intelligence, or immoral, criminal or anti-social behavior. Beginning with Connecticut in 1896, states passed laws requiring medical exams before issuing marriage licenses to make sure the unfit did not reproduce. (See the New York Times article “Pastors for Eugenics” for an effort to support such laws.) Indiana passed the first compulsory sterilization law in 1907, although other states had tried and failed before. Prominent Americans – among them Theodore Roosevelt, Stanford University President David Starr Jordan, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Margaret Sanger – supported the eugenics movement, as did such organizations as the National Federation of Women’s Clubs, the National Conference of Charities and Corrections, and various religious organizations. State Fairs included Better Baby contests. As the list of its supporters indicates, eugenics was considered a progressive reform, related to the larger Progressive movement by its emphasis on the good of society and the use of science and rationality to achieve it.

Eugenics always had its critics. A referendum authorizing sterilization failed in Oregon in 1913. Some governors refused to sign eugenic legislation. Nebraska’s governor vetoed a eugenics bill in 1913, writing that the legislation was “only an experiment and it seems more in keeping with the pagan age than with the teachings of Christianity. Man is more than an animal.” Not every state legislature passed such legislation. Federal and state courts regularly found forced sterilization laws unconstitutional because they were cruel and unusual punishments or because the application of the laws denied equal treatment. In addition to more conservative Protestants, Catholics and their clergy largely opposed eugenics.

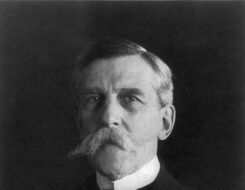

Despite the opposition it faced, eugenic sterilization remained alive in part because of the Supreme Court decision Buck v. Bell, which found constitutional the sterilization of Carrie Buck by the State of Virginia. From the beginning, Buck’s sterilization was intended to be a test case. Supporters of eugenics and sterilization hoped the case would reach the Supreme Court and that the Court would find sterilization constitutional. This would at once supersede all the rulings of state courts against sterilization. Buck’s guardian, appointed by those intending to sterilize her, took her case to Virginia state courts and eventually the Supreme Court. (The lower Virginia court found no grounds to block the sterilization.) The Supreme Court decided that nothing in the U.S. Constitution prevented Virginia from sterilizing Buck. Eight of nine justices joined in the decision, written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, perhaps the preeminent jurist of the time. Holmes’ decision contained the now infamous remark, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” The only dissent in the case came from Associate Justice Pierce Butler, a Catholic.

Sterilization continued as a legal regime even after eugenics ceased to be a popular movement. Thirty-one states eventually had sterilization programs, often adopting the language of the Virginia legislation that the Supreme Court approved, which had been drafted by a lawyer to increase its chances of meeting legal scrutiny. Sterilizations increased and did not cease until the 1960s. (The sterilization program in North Carolina lasted until 1977.) California, a leading Progressive state, sterilized about 20,000 people, a third or so of the almost 70,000 individuals sterilized in the United States.

Toward the end of his discussion of eugenics, G. Stanley Hall wrote of “the kingdom of some kind of superman” to which eugenics might lead. This remark foreshadowed the darkness of the Holocaust and reminds us that Hitler cited America’s eugenics movement and laws as a precedent.

Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927). Available online at Justia. https://goo.gl/mn3RFr

Mr. JUSTICE HOLMES delivered the opinion of the Court.

This is a writ of error to review a judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeals of the State of Virginia affirming a judgment of the Circuit Court of Amherst County by which the defendant in error,1 the superintendent of the State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble Minded, was ordered to perform the operation of salpingectomy upon Carrie Buck, the plaintiff in error, for the purpose of making her sterile.2 143 Va. 310. The case comes here upon the contention that the statute authorizing the judgment is void under the Fourteenth Amendment as denying to the plaintiff in error due process of law and the equal protection of the laws.

Carrie Buck is a feeble minded white woman who was committed to the State Colony above mentioned in due form.3 She is the daughter of a feeble minded mother in the same institution, and the mother of an illegitimate feeble minded child. She was eighteen years old at the time of the trial of her case in the Circuit Court, in the latter part of 1924.

An Act of Virginia, approved March 20, 1924, recites that the health of the patient and the welfare of society may be promoted in certain cases by the sterilization of mental defectives, under careful safeguard, &c.; that the sterilization may be effected in males by vasectomy and in females by salpingectomy, without serious pain or substantial danger to life; that the Commonwealth is supporting in various institutions many defective persons who, if now discharged, would become a menace, but, if incapable of procreating, might be discharged with safety and become self-supporting with benefit to themselves and to society, and that experience has shown that heredity plays an important part in the transmission of insanity, imbecility, &c.

The statute then enacts that, whenever the superintendent of certain institutions, including the above-named State Colony, shall be of opinion that it is for the best interests of the patients and of society that an inmate under his care should be sexually sterilized, he may have the operation performed upon any patient afflicted with hereditary forms of insanity, imbecility, &c., on complying with the very careful provisions by which the act protects the patients from possible abuse.

The superintendent first presents a petition to the special board of directors of his hospital or colony, stating the facts and the grounds for his opinion, verified by affidavit. Notice of the petition and of the time and place of the hearing in the institution is to be served upon the inmate, and also upon his guardian, and if there is no guardian, the superintendent is to apply to the Circuit Court of the County to appoint one. If the inmate is a minor, notice also is to be given to his parents, if any, with a copy of the petition. The board is to see to it that the inmate may attend the hearings if desired by him or his guardian.

The evidence is all to be reduced to writing, and, after the board has made its order for or against the operation, the superintendent, or the inmate, or his guardian, may appeal to the Circuit Court of the County. The Circuit Court may consider the record of the board and the evidence before it and such other admissible evidence as may be offered, and may affirm, revise, or reverse the order of the board and enter such order as it deems just. Finally, any party may apply to the Supreme Court of Appeals, which, if it grants the appeal, is to hear the case upon the record of the trial in the Circuit Court, and may enter such order as it thinks the Circuit Court should have entered.

There can be no doubt that, so far as procedure is concerned, the rights of the patient are most carefully considered, and, as every step in this case was taken in scrupulous compliance with the statute and after months of observation, there is no doubt that, in that respect, the plaintiff in error has had due process of law. The attack is not upon the procedure, but upon the substantive law. It seems to be contended that in no circumstances could such an order be justified. It certainly is contended that the order cannot be justified upon the existing grounds.

The judgment finds the facts that have been recited, and that Carrie Buck “is the probable potential parent of socially inadequate offspring, likewise afflicted, that she may be sexually sterilized without detriment to her general health, and that her welfare and that of society will be promoted by her sterilization,” and thereupon makes the order. In view of the general declarations of the legislature and the specific findings of the Court, obviously we cannot say as matter of law that the grounds do not exist, and, if they exist, they justify the result.

We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11.4 Three generations of imbeciles are enough.

But, it is said, however it might be if this reasoning were applied generally, it fails when it is confined to the small number who are in the institutions named and is not applied to the multitudes outside. It is the usual last resort of constitutional arguments to point out shortcomings of this sort. But the answer is that the law does all that is needed when it does all that it can, indicates a policy, applies it to all within the lines, and seeks to bring within the lines all similarly situated so far and so fast as its means allow. Of course, so far as the operations enable those who otherwise must be kept confined to be returned to the world, and thus open the asylum to others, the equality aimed at will be more nearly reached.

Judgment affirmed.

JUSTICE BUTLER dissents.

- 1. The party in a legal appeal. It does not mean that the defendant was wrong or guilty.

- 2. A salpingectomy is the removal of one or both Fallopian tubes.

- 3. For the facts of the case, the Court relied on the Virginia trial record. Most of the facts it presented, which Justice Holmes summarized in his opinion, were wrong. For example, Buck was not feeble-minded, nor was her mother. Buck apparently became pregnant because she was raped, rather than because she was licentious. In the hearing that resulted in the decision to sterilize her, Buck was represented by someone who favored sterilization.

- 4. A 1905 decision by the Supreme Court that upheld a compulsory vaccination law in Massachusetts. The Court argued that “. . . the liberty secured by the Constitution of the United States to every person within its jurisdiction does not import an absolute right in each person to be, at all times and in all circumstances, wholly freed from restraint. There are manifold restraints to which every person is necessarily subject for the common good. On any other basis organized society could not exist with safety to its members. Society based on the rule that each one is a law unto himself would soon be confronted with disorder and anarchy.” Accordingly, the Court ruled that compulsory vaccination was within the legitimate police power of the state. See Jacobson v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11, 12 (1905). https://goo.gl/fKBdgP.

Whitney v. California

May 16, 1927

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.