No related resources

Introduction

In 1968, the Democratic Party nominated Hubert Humphrey even though he did not win a single primary. Lyndon Johnson chose not to run for reelection after a narrower than expected victory over Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy. McCarthy was opposed to the Vietnam War and his surprising showing in New Hampshire, combined with Johnson’s exit, brought in New York Senator Robert Kennedy, who also appealed to anti-war voters. After Kennedy’s assassination, South Dakota Senator George McGovern entered the race, also campaigning against the war in Vietnam. At the Democratic Convention in Chicago, party leaders nominated Humphrey, sparking protests from the anti-war faction of the party.

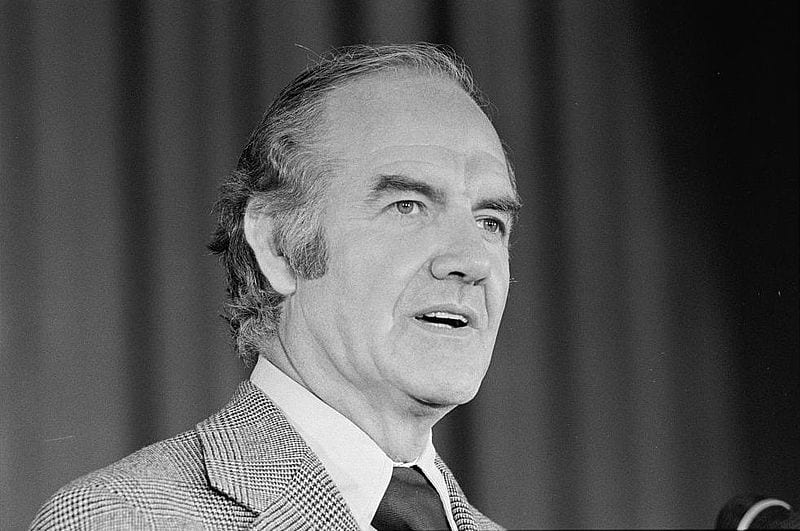

Humphrey’s victory was the last in the so-called mixed system of presidential nomination history, and its controversy ushered in reforms that would lead to the current system. From 1912 to 1968, many states held primaries, but these were largely non-binding contests to determine whom party members preferred. Candidates would enter select primaries to demonstrate their strength among voters to party leaders, but a victory in a primary was not a guarantee of the state’s delegates. Discontent with this system led to the creation of the Democratic Party’s Commission on Delegate Selection and Party Structure, also called the McGovern-Fraser Commission after its co-chairs. The Commission laid the foundation for the current nominating process, which requires that delegates be awarded based on results in primaries and caucuses. This move democratized the nomination process, taking it away from the control of party leaders.

Source: Congressional Record, 92nd Congress, First Session, Volume 117, Part 25 (Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1971), 32909-32910.

MANDATE FOR REFORM

The 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago exposed profound flaws in the presidential nominating process; but in so doing it gave our Party an excellent opportunity to reform its ways and to prepare for the problems of a new decade.

The delegates to the Convention, concerned by the chaos and divisiveness, shared a belief that the image of an organization impervious to the will of its rank and file threatened the future of the Party. Therefore, they took up the challenge of reform with a mandate requiring state Parties to give “all Democratic voters . . . a full, meaningful, and timely opportunity to participate” in the selection of delegates, and, thereby, in the decisions of the Convention itself.[1]

In order to ensure that this mandate would be implemented, the Convention directed the Democratic National Committee to establish a Commission to aid state Parties in meeting the Convention requirement.

In February 1969, Senator Fred Harris,[2] Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, appointed us to that body mandated by the Convention – The Commission on Party Structure and Delegate Selection. We are Democrats who represent every segment of our Party. We find common cause in our Party’s history of fair play and equal opportunity. We believe that the continuing vitality of the Democratic Party depends upon its adherence to this heritage.

Since its inception, our Party has been an open party – open to new ideas and new people. From the days of Jefferson and Jackson, the Democratic Party has been committed to the broad participation of rank-and-file members in all of its major decision-making.

In the American two-party system, no decision is more important to the rank-and-file member than the choice of the party’s presidential nominee. For this reason, popular control over the nominating process has been a principle of the Democratic Party since the birth of the National Convention 140 years ago.

This tradition for participation and popular control, however, has not always been adequately expressed. After a lengthy examination of the structures and processes used to select delegates to the National Convention in 1968, this is our basic conclusion: meaningful participation of Democratic voters in the choice of their presidential nominee was often difficult or costly, sometimes completely illusory, and, in not a few instances, impossible.

Among the findings the Commission has made about delegate selection in 1968 are the following:

In at least twenty states, there were no (or inadequate) rules for the selection of Convention delegates, leaving the entire process to the discretion of a handful of party leaders.

More than a third of the Convention delegates had, in effect, already been selected prior to 1968 – before either the major issues or the possible presidential candidates were known. By the time President Johnson announced his withdrawal from the nomination contest, the delegate selection process had begun in all but twelve states.

Unrestrained use or application of majority rule was the cause of much strain among Democrats in 1968. The imposition of the unit rule from the first to final stage of the nominating process, the enforcement of binding instructions on delegates, and favorite-son candidacies were all devices used to force Democrats to vote against their stated presidential preferences. Additionally, in primary, convention and committee systems, majorities used their numerical superiority to deny delegate representation to the supporters of minority presidential candidates.

Secret caucuses, closed slate-making, widespread proxy voting – and a host of other procedural irregularities – were all too common at precinct, country, district, and state conventions.

In many states, the costs of participation in the process of delegate selection were clearly discriminatory; in others, they were prohibitive. Filing fees for entering primaries were often excessive, reaching $14,000 in one state, if a complete slate of candidates had been filed. “Hospitality” fees were often imposed on delegates to the convention, reaching $500 in one delegation. Not surprisingly, only 13% of the delegates to the National Convention had incomes of under $10,000 (whereas 70% of the population have annual incomes under that amount).

Representation of blacks, women and youth at the Convention was substantially below the proportion of each group in the population. Blacks comprised about five percent of the voting delegates, well above their numbers in 1964; since blacks make up 11% of the population and supplied at least 20% of the total vote for the Democratic presidential candidate, however, they were still underrepresented at the Convention. Women comprised only 13% of the delegates with only one of 55 delegations having a woman chairman. In a majority of delegations there was no more than a single delegate under 30 years of age, and in two delegations the average age was 54. The delegates to the 1968 Democratic National Convention, in short, were predominantly white, male, middle-aged, and at least middle-class.

As this information emerged, we recognized that two alternative courses of action were available to us. First, we could suggest that the institution of the National Convention had outlived its usefulness and should be discarded. To be sure, at our public hearings several Democrats gave testimony expressing the judgment that the convention system did not deserve to be saved. There was a substantial body of feeling, in fact, that a national primary within each Party would be the most democratic means of selecting presidential candidates.

Second, we could conclude that there was nothing inherently undemocratic about a National Convention: that 1968 was a culmination of years of indifference to the nominating process, rather than a startling aberration from previous years; that purged of its structural and procedural inadequacies, the National Convention was an institution well worth preserving. The Commission has taken this second course. The following are some of our reasons:

In view of the stringent demands made upon a President of the United States, the challenge imposed upon any contender for the nomination in seeking support in a wide variety of delegate selection systems should be maintained.

The face-to-face confrontation of Democrats of every persuasion in a periodic mass meeting is productive of healthy debate, important policy decisions (usually in the form of platform planks), reconciliation of differences, and realistic preparation for the fall presidential campaign.

The Convention provides a mechanism for party self-government through the election and instruction of a National Committee.

While endorsing the institution, the Commission believes that if delegates are not chosen in a democratic manner, the National Convention cannot perform its functions adequately. In order to ensure the democratic selection of delegates, the Commission has adopted Eighteen Guidelines binding on all state Parties.

These Guidelines represent the Commission’s interpretation of its mandate to ensure that all Democrats are provided a full, meaningful, and timely opportunity to participate in the delegate selection process. To this end, the requirements and recommendations of the Guidelines are directed toward the elimination of regulation of:

(a) Rules or practices which inhibit access to the delegate selection process – items which compromise full and meaningful participation by inhibiting or preventing a Democrat from exercising his influence in the delegate selection process;

(b) Rules or practices which dilute the influence of a Democrat in the delegate selection process, after he has exercised all available resources to effect such influence.

(c) Rules and practices which have the combined effect of inhibiting access and diluting influence.

The Commission believes that there is no one selection system ideal for all states. Therefore, we did not find it desirable to lay down uniform rules for delegate selection in the Guidelines.

Instead, we have adopted certain minimum standards of fairness, that all states are expected to meet. Once these standards are met, state Parties are free to adopt any procedures they may prefer. The Commission believes that this preservation of local genius is an important element of a healthy National Convention.

These Guidelines are meant to serve no ideology and no geographic segment of our Party. They are designed to stimulate the participation of all Democrats in the nominating process and to re-establish public confidence in the National Convention.

The Commission has proceeded in its work against a backdrop of genuine unhappiness and mistrust of millions of Americans with our political system. We are aware that political parties are not the only way of organizing political life. Political parties will survive only if they respond to the needs and concerns of their members.

In adopting our Guidelines and in presenting this report, we have been guided by the firm belief that the Democratic Party is incapable of closing its eyes and ears to this unhappiness and mistrust. While the Republican response to popular demands for more participation and open processes has been indifference, the Democrats have chosen to face the matter head on.

Our Party’s longevity is due in no small way to its capacity to respond to these demands in a positive fashion. We are confident that it will do so again.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.