Introduction

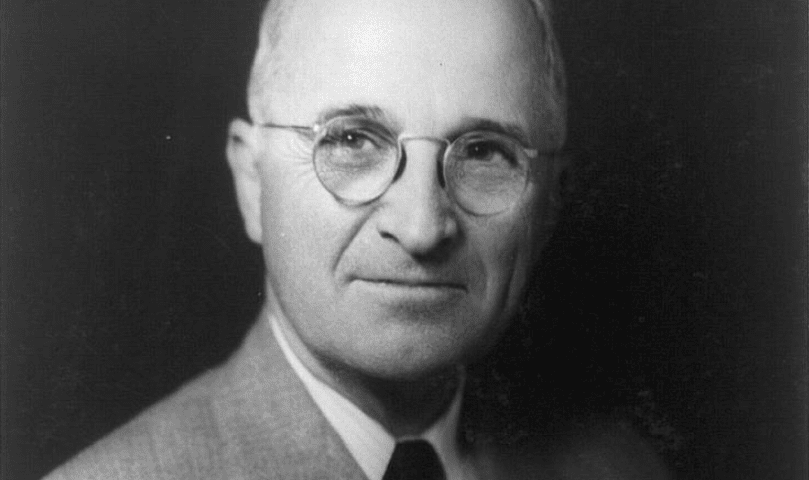

The Korean War was the first major armed conflict of the Cold War. It tested the commitment of the United States to containment and raised a significant question about the end goal of the U.S. Cold War policy: should it seek only to stop the spread of communism or should it also try to roll back communism? Unexpected developments in the war led to a clash between President Harry Truman and his top general in Korea, Douglas MacArthur, as these documents show.

The war’s origins lay in the troubled division of Korea into South Korea and North Korea following Japan’s defeat in World War II, which brought to an end the Japanese occupation of Korea (1910 – 1945). North Korea was communist; the South anti-communist.

On June 25, 1950, North Korean forces carried out a massive invasion of the South. Soviet leader Josef Stalin had approved of – but had not ordered – the action, but Soviet military aid to North Korea seemed to confirm the prediction of NSC 68 that the communists sought world domination. President Truman, Secretary of State Dean Acheson, and top-level national security and military officials agreed that the United States and its allies must act immediately to protect South Korea. Although Acheson had suggested in January that the United States would not deploy its military forces outside of the so-called defensive perimeter in Asia, he also stated that an attacked nation could rely on the United Nations. American military action was therefore enabled by U.N. Security Council decisions. U.N. forces in Korea included those from the United States and 16 other nations.

A risky amphibious landing at Inchon (September 1950), conceived and commanded by General Douglas MacArthur, turned the tide of battle in favor of U.N. forces, which advanced toward the line of division between the two Koreas, recovering ground lost to the North and then, with the urging of MacArthur, into North Korea itself, eventually approaching the border with China. In response to the U.N. advance, China sent its forces into North Korea (October 1950), causing the U.N. forces to retreat and leading eventually to a stalemate along the original line dividing North and South Korea.

Chinese intervention drastically raised the stakes of the war. If Truman ordered U.N. forces to retreat to South Korean territory, he risked criticism that the decision to invade North Korea was a mistake. But efforts to force a Chinese withdrawal were certain to prolong the war and result in increased U.S. casualties. Aggressive statements by MacArthur calling for a direct attack on China further complicated Truman’s position. Truman decided to relieve MacArthur of his command for insubordination. (The general had defied orders that he clear his public statements with the White House before their release.) Truman announced his decision on April 11, 1951, the day he also delivered this speech.

MacArthur did not go quietly. Congressional leaders invited him to address both houses, and the general used the occasion to defend his ideas for winning the Korean War. MacArthur famously declared, “In war there is no substitute for victory.” Hailed as a hero, he embarked on a national tour, basking in the cheers of adoring crowds in numerous cities. He briefly flirted with running for president as a Republican but soon faded from public view. Truman’s popularity fell, but in hindsight his decision to protect the chain of command was a wise one. What hurt Truman more was the grinding stalemate of the Korean War. With his approval ratings at an all-time low, he decided not to seek re-election in 1952. The task of ending the war fell to his successor, Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, who brokered a cease-fire in July 1953 that restored the prewar situation: Korea remained divided; a communist regime still held power in the North.

Source: Report to the American People on Korea, University of Virginia, Miller Center. April 11, 1951. Available at https://goo.gl/5eM2yQ.

I want to talk to you plainly tonight about what we are doing in Korea and about our policy in the Far East.

In the simplest terms, what we are doing in Korea is this: We are trying to prevent a third world war.

I think most people in this country recognized that fact last June. And they warmly supported the decision of the Government to help the Republic of Korea against the Communist aggressors. . . .

The Communists in the Kremlin are engaged in a monstrous conspiracy to stamp out freedom all over the world. If they were to succeed, the United States would be numbered among their principal victims. It must be clear to everyone that the United States cannot – and will not – sit idly by and await foreign conquest. The only question is: What is the best time to meet the threat and how is the best way to meet it?

The best time to meet the threat is in the beginning. It is easier to put out a fire in the beginning when it is small than after it has become a roaring blaze. And the best way to meet the threat of aggression is for the peace-loving nations to act together. If they don’t act together, they are likely to be picked off, one by one.

If they had followed the right policies in the 1930’s – if the free countries had acted together to crush the aggression of the dictators, and if they had acted in the beginning when the aggression was small – there probably would have been no World War II.

If history has taught us anything, it is that aggression anywhere in the world is a threat to the peace everywhere in the world. When that aggression is supported by the cruel and selfish rulers of a powerful nation who are bent on conquest, it becomes a clear and present danger to the security and independence of every free nation.

This is a lesson that most people in this country have learned thoroughly. This is the basic reason why we joined in creating the United Nations. And, since the end of World War II, we have been putting that lesson into practice – we have been working with other free nations to check the aggressive designs of the Soviet Union before they can result in a third world war.

That is what we did in Greece, when that nation was threatened by the aggression of international communism.1

The attack against Greece could have led to general war. But this country came to the aid of Greece. The United Nations supported Greek resistance. With our help, the determination and efforts of the Greek people defeated the attack on the spot. . . .

The aggression against Korea is the boldest and most dangerous move the Communists have yet made.

The attack on Korea was part of a greater plan for conquering all of Asia. . . .

This plan of conquest is in flat contradiction to what we believe. We believe that Korea belongs to the Koreans, we believe that India belongs to the Indians, we believe that all the nations of Asia should be free to work out their affairs in their own way. This is the basis of peace in the Far East, and it is the basis of peace everywhere else. . . .

The question we have had to face is whether the Communist plan of conquest can be stopped without a general war. Our Government and other countries associated with us in the United Nations believe that the best chance of stopping it without a general war is to meet the attack in Korea and defeat it there.

That is what we have been doing. It is a difficult and bitter task.

But so far it has been successful.

So far, we have prevented world war III.

So far, by fighting a limited war in Korea, we have prevented aggression from succeeding, and bringing on a general war. And the ability of the whole free world to resist Communist aggression has been greatly improved.

We have taught the enemy a lesson. He has found that aggression is not cheap or easy. Moreover, men all over the world who want to remain free have been given new courage and new hope. They know now that the champions of freedom can stand up and fight, and that they will stand up and fight. . . .

The Communist side must now choose its course of action. The Communist rulers may press the attack against us. They may take further action which will spread the conflict. They have that choice, and with it the awful responsibility for what may follow. The Communists also have the choice of a peaceful settlement which could lead to a general relaxation of the tensions in the Far East. The decision is theirs, because the forces of the United Nations will strive to limit the conflict if possible. . . .

But you may ask why can’t we take other steps to punish the aggressor. Why don’t we bomb Manchuria2 and China itself? Why don’t we assist the Chinese Nationalist troops to land on the mainland of China?3

If we were to do these things we would be running a very grave risk of starting a general war. If that were to happen, we would have brought about the exact situation we are trying to prevent.

If we were to do these things, we would become entangled in a vast conflict on the continent of Asia and our task would become immeasurably more difficult all over the world. . . .

Our aim is to avoid the spread of the conflict.

The course we have been following is the one best calculated to avoid an all-out war. It is the course consistent with our obligation to do all we can to maintain international peace and security. Our experience in Greece . . . shows that it is the most effective course of action we can follow.

First of all, it is clear that our efforts in Korea can blunt the will of the Chinese Communists to continue the struggle. The United Nations forces have put up a tremendous fight in Korea and have inflicted very heavy casualties on the enemy. Our forces are stronger now than they have been before. These are plain facts which may discourage the Chinese Communists from continuing their attack.

Second, the free world as a whole is growing in military strength every day. In the United States, in Western Europe, and throughout the world, free men are alert to the Soviet threat and are building their defenses. This may discourage the Communist rulers from continuing the war in Korea – and from undertaking new acts of aggression elsewhere.

If the Communist authorities realize that they cannot defeat us in Korea, if they realize it would be foolhardy to widen the hostilities beyond Korea, then they may recognize the folly of continuing their aggression. A peaceful settlement may then be possible. The door is always open.

Then we may achieve a settlement in Korea which will not compromise the principles and purposes of the United Nations.

I have thought long and hard about this question of extending the war in Asia. I have discussed it many times with the ablest military advisers in the country. I believe with all my heart that the course we are following is the best course.

I believe that we must try to limit the war to Korea for these vital reasons: to make sure that the precious lives of our fighting men are not wasted; to see that the security of our country and the free world is not needlessly jeopardized; and to prevent a third world war.

A number of events have made it evident that General MacArthur did not agree with that policy. I have therefore considered it essential to relieve General MacArthur so that there would be no doubt or confusion as to the real purpose and aim of our policy.

It was with the deepest personal regret that I found myself compelled to take this action. General MacArthur is one of our greatest military commanders. But the cause of world peace is much more important than any individual.

The change in commands in the Far East means no change whatever in the policy of the United States. We will carry on the fight in Korea with vigor and determination in an effort to bring the war to a speedy and successful conclusion. . . .

- 1. See Truman's Special Message to the Congress on Greece and Turkey (The Truman Doctrine), March 12, 1947.

- 2. Northern China.

- 3. After losing China’s civil war to the communists, the Chinese nationalists – whom the United States had supported – retreated to the island of Taiwan, then called Formosa.

Address to Congress

April 19, 1951

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.