No related resources

Introduction

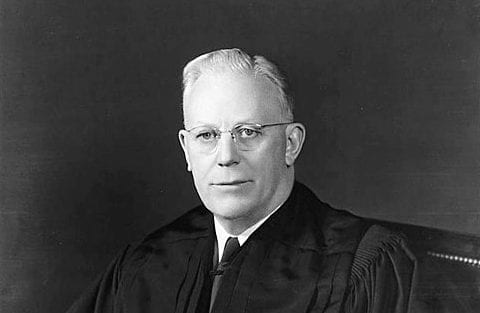

This landmark decision was one of the most consequential of Chief Justice Earl Warren’s (1891–1974) career. Every ten years, states redraw congressional and state legislative district lines. However, during the first half of the twentieth century many states neglected to do so. As state populations shifted from rural to urban areas, many districts became imbalanced, with rural districts having far fewer voters. Since urban areas often had larger black populations, this contributed to the systematic underrepresentation of minorities. Until Baker v. Carr (1962) the Supreme Court had consistently ruled that reapportionment and redistricting were political questions not suitable for judicial resolution. The political question doctrine had its origins in Marbury v. Madison (1803), which held that “questions in their nature political or which are, by the Constitution and laws, submitted to the Executive, can never be made in this court.” Traditionally, following the language of Marbury, the two main standards for determining if a case raised a political question were (1) are the issues in the case constitutionally committed to another branch of government? and (2) are there judicially discoverable and manageable standards for resolving the case? For example, in Nixon v. United States (1993), which involved an impeached federal judge, the Supreme Court said that the Constitution commits the “sole power” to “try all impeachments” to the Senate and that the word “try” is too imprecise for the Court to craft any “judicially manageable standard” to review the Senate’s procedures. In Baker, the Supreme Court reversed itself and said that malapportionment raised an equal protection issue resolvable by the courts.

Having decided that it could review the drawing of district lines, the Court still needed to decide what standard would apply. In Wesberry v. Sanders (1963) and Reynolds v. Sims it decided upon the one-person, one-vote principle to apportion congressional and state legislative districts. Sims had been filed in the aftermath of Carr when several Alabama voters challenged the state senate district lines, which had not been modified since 1901. The state constitution said that there should be only one senator per county. The Court’s 8–1 majority opinion, written by Chief Justice Warren, said that this sort of malapportionment was in practice no different from letting some voters vote multiple times and limiting others to voting once. “Legislators represent people, not trees or acres,” he famously wrote. As well, the right to vote is “preservative of other basic civil and political rights” since citizens seek to protect their interests and rights through the political process. Thus, the Court must “carefully and meticulously scrutinize” infringements of the right to vote.

The lone dissenter, Justice John Marshall Harlan II (1899–1971), argued that the Court was wading into an area where it had no special competence. States, he predicted, being unable to draw lines based on geographic or jurisdictional lines, would engage in increased partisan gerrymandering that would have the same effect as malapportionment. Since Reynolds, the Court has held that partisan gerrymandering raises a political question since there are no manageable judicial standards to distinguish constitutional versus unconstitutional gerrymandering. Harlan also criticized the idea that every social ill has a constitutional cure: “The Constitution is not a panacea for every blot upon the public welfare.” But most importantly, he contended that over the long run, these sorts of decisions, which were designed to vindicate rights and protect liberty, would do the opposite. Consolidating greater authority in the Court would compromise the dispersion of power that protects liberty.

Source: 377 U.S. 533; https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/377/533.

Mr. Chief Justice WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court.

. . . Undeniably, the Constitution of the United States protects the right of all qualified citizens to vote, in state as well as in federal elections. . . .The right to vote can neither be denied outright nor destroyed by alteration of ballots, nor diluted by ballot-box stuffing. . . .Racially based gerrymandering, and the conducting of white primaries1. . . have been held to be constitutionally impermissible. And history has seen a continuing expansion of the scope of the right of suffrage in this country. The right to vote freely for the candidate of one’s choice is of the essence of a democratic society, and any restrictions on that right strike at the heart of representative government. And the right of suffrage can be denied by a debasement or dilution of the weight of a citizen’s vote just as effectively as by wholly prohibiting the free exercise of the franchise.

In Baker v. Carr (1962), we held that a claim asserted under the equal protection clause [of the Fourteenth Amendment] challenging the constitutionality of a state’s apportionment of seats in its legislature, on the ground that the right to vote of certain citizens was effectively impaired, since debased and diluted, in effect presented a justiciable controversy subject to adjudication by federal courts. The spate of similar cases filed and decided by lower courts since our decision in Baker amply shows that the problem of state legislative malapportionment is one that is perceived to exist in a large number of the states. In Baker, . . .[w]e intimated no view as to the proper constitutional standards for evaluating the validity of a state legislative apportionment scheme. Nor did we give any consideration to the question of appropriate remedies. . . . Subsequent to Baker, we remanded several cases to the courts below for reconsideration in light of that decision. . . .

. . .[I]n these cases, we are faced with the problem. . . of determining the basic standards and stating the applicable guidelines for implementing our decision in Baker v. Carr.

In Wesberry v. Sanders, decided earlier this term, . . .[w]e concluded that the constitutional prescription for election of members of the House of Representatives “by the People,” construed in its historical context, “means that, as nearly as is practicable, one man’s vote in a congressional election is to be worth as much as another’s.”. . .

… Wesberry clearly established that the fundamental principle of representative government in this country is one of equal representation for equal numbers of people, without regard to race, sex, economic status, or place of residence within a state. Our problem, then, is to ascertain, in the instant cases,2 whether there are any constitutionally cognizable principles which would justify departures from the basic standard of equality among voters in the apportionment of seats in state legislatures.

A predominant consideration in determining whether a state’s legislative apportionment scheme constitutes an invidious discrimination violative of rights asserted under the equal protection clause is that the rights allegedly impaired are individual and personal in nature. . . . Undoubtedly, the right of suffrage is a fundamental matter in a free and democratic society. Especially since the right to exercise the franchise in a free and unimpaired manner is preservative of other basic civil and political rights, any alleged infringement of the right of citizens to vote must be carefully and meticulously scrutinized. . . .

Legislators represent people, not trees or acres. Legislators are elected by voters, not farms or cities or economic interests. As long as ours is a representative form of government, and our legislatures are those instruments of government elected directly by and directly representative of the people, the right to elect legislators in a free and unimpaired fashion is a bedrock of our political system. . . .And, if a state should provide that the votes of citizens in one part of the State should be given two times, or five times, or ten times the weight of votes of citizens in another part of the state, it could hardly be contended that the right to vote of those residing in the disfavored areas had not been effectively diluted. . . . Of course, the effect of state legislative districting schemes which give the same number of representatives to unequal numbers of constituents is identical. Overweighting and overvaluation of the votes of those living here has the certain effect of dilution and undervaluation of the votes of those living there. The resulting discrimination against those individual voters living in disfavored areas is easily demonstrable mathematically. Their right to vote is simply not the same right to vote as that of those living in a favored part of the state. Two, five, or ten of them must vote before the effect of their voting is equivalent to that of their favored neighbor. Weighting the votes of citizens differently, by any method or means, merely because of where they happen to reside, hardly seems justifiable. One must be ever aware that the Constitution forbids “sophisticated, as well as simple-minded, modes of discrimination.”3…

. . .[R]epresentative government is, in essence, self-government through the medium of elected representatives of the people, and each and every citizen has an inalienable right to full and effective participation in the political processes of his state’s legislative bodies. Most citizens can achieve this participation only as qualified voters through the election of legislators to represent them. Full and effective participation by all citizens in state government requires, therefore, that each citizen have an equally effective voice in the election of members of his state legislature. Modern and viable state government needs, and the Constitution demands, no less. . . .

. . . Since the achieving of fair and effective representation for all citizens is concededly the basic aim of legislative apportionment, we conclude that the equal protection clause guarantees the opportunity for equal participation by all voters in the election of state legislators. Diluting the weight of votes because of place of residence impairs basic constitutional rights under the Fourteenth Amendment just as much as invidious discriminations based upon factors such as race. Our constitutional system amply provides for the protection of minorities by means other than giving them majority control of state legislatures. And the democratic ideals of equality and majority rule, which have served this nation so well in the past, are hardly of any less significance for the present and the future.

We are told that the matter of apportioning representation in a state legislature is a complex and many-faceted one. We are advised that states can rationally consider factors other than population in apportioning legislative representation. We are admonished not to restrict the power of the states to impose differing views as to political philosophy on their citizens. We are cautioned about the dangers of entering into political thickets and mathematical quagmires. Our answer is this: a denial of constitutionally protected rights demands judicial protection; our oath and our office require no less of us. . . .

. . .A citizen, a qualified voter, is no more nor no less so because he lives in the city or on the farm. This is the clear and strong command of our Constitution’s equal protection clause. This is an essential part of the concept of a government of laws and not men. This is at the heart of Lincoln’s vision of “government of the people, by the people, [and] for the people.” The equal protection clause demands no less than substantially equal state legislative representation for all citizens, of all places as well as of all races. . . .

We do not believe that the concept of bicameralism is rendered anachronistic and meaningless when the predominant basis of representation in the two state legislative bodies is required to be the same population. A prime reason for bicameralism, modernly considered, is to ensure mature and deliberate consideration of, and to prevent precipitate action on, proposed legislative measures. Simply because the controlling criterion for apportioning representation is required to be the same in both houses does not mean that there will be no differences in the composition and complexion of the two bodies. Different constituencies can be represented in the two houses. One body could be composed of single member districts while the other could have at least some multi-member districts. The length of terms of the legislators in the separate bodies could differ. The numerical size of the two bodies could be made to differ, even significantly, and the geographical size of districts from which legislators are elected could also be made to differ. And apportionment in one house could be arranged so as to balance off minor inequities in the representation of certain areas in the other house. In summary, these and other factors could be, and are presently in many states, utilized to engender differing complexions and collective attitudes in the two bodies of a state legislature, although both are apportioned substantially on a population basis. . . .

We do not consider here the difficult question of the proper remedial devices which federal courts should utilize in state legislative apportionment cases. Remedial techniques in this new and developing area of the law will probably often differ with the circumstances of the challenged apportionment and a variety of local conditions. It is enough to say now that, once a state’s legislative apportionment scheme has been found to be unconstitutional, it would be the unusual case in which a court would be justified in not taking appropriate action to ensure that no further elections are conducted under the invalid plan. However, under certain circumstances, such as where an impending election is imminent and a state’s election machinery is already in progress, equitable considerations might justify a court in withholding the granting of immediately effective relief in a legislative apportionment case, even though the existing apportionment scheme was found invalid. In awarding or withholding immediate relief, a court is entitled to and should consider the proximity of a forthcoming election and the mechanics and complexities of state election laws, and should act and rely upon general equitable principles. With respect to the timing of relief, a court can reasonably endeavor to avoid a disruption of the election process which might result from requiring precipitate changes that could make unreasonable or embarrassing demands on a state in adjusting to the requirements of the court’s decree. . . .

. . . Since the District Court evinced its realization that its ordered reapportionment could not be sustained as the basis for conducting the 1966 election of Alabama legislators, and avowedly intends to take some further action should the reapportioned Alabama Legislature fail to enact a constitutionally valid, permanent apportionment scheme in the interim, we affirm the judgment below and remand4 the cases for further proceedings consistent with the views stated in this opinion.

It is so ordered.

Justice HARLAN, dissenting:

In these cases, the Court holds that seats in the legislatures of six states are apportioned in ways that violate the federal Constitution. Under the Court’s ruling it is bound to follow that the legislatures in all but a few of the other forty-four states will meet the same fate. These decisions. . . have the effect of placing basic aspects of state political systems under the pervasive overlordship of the federal judiciary. Once again, I must register my protest. . . .

The Court’s constitutional discussion . . . is remarkable . . . for its failure to address itself at all to the Fourteenth Amendment as a whole or to the legislative history of the amendment pertinent to the matter at hand. Stripped of aphorisms, the Court’s argument boils down to the assertion that [Sims’] right to vote has been invidiously “debased” or “diluted” by systems of apportionment which entitle [him] to vote for fewer legislators than other voters, an assertion which is tied to the equal protection clause only by the constitutionally frail tautology that “equal” means “equal.”

Had the Court paused to probe more deeply into the matter, it would have found that the equal protection clause was never intended to inhibit the states in choosing any democratic method they pleased for the apportionment of their legislatures. This is shown by the language of the Fourteenth Amendment taken as a whole, by the understanding of those who proposed and ratified it, and by the political practices of the states at the time the amendment was adopted. It is confirmed by numerous state and congressional actions since the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, and by the common understanding of the amendment as evidenced by subsequent constitutional amendments and decisions of this Court before Baker v. Carr made an abrupt break with the past in 1962.

The failure of the Court to consider any of these matters cannot be excused or explained by any concept of “developing” constitutionalism. It is meaningless to speak of constitutional “development” when both the language and history of the controlling provisions of the Constitution are wholly ignored. Since it can, I think, be shown beyond doubt that state legislative apportionments, as such, are wholly free of constitutional limitations, save such as may be imposed by the republican form of government clause (Constitution, Article IV, section 4), the Court’s action now bringing them within the purview of the Fourteenth Amendment amounts to nothing less than an exercise of the amending power by this Court. . . .

The Court relies exclusively on that portion of the Fourteenth Amendment which provides that no state shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws,” and disregards entirely the significance of section 2, which reads:

Representatives shall be apportioned among the several states according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each state, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for president and vice president of the United States, representatives in Congress, the executive and judicial officers of a state, or the members of the legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such state, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such state.

The amendment is a single text. It was introduced and discussed as such in the Reconstruction Committee, which reported it to the Congress. It was discussed as a unit in Congress and proposed as a unit to the states, which ratified it as a unit. A proposal to split up the amendment and submit each section to the states as a separate amendment was rejected by the Senate. Whatever one might take to be the application to these cases of the equal protection clause if it stood alone, I am unable to understand the Court’s utter disregard of the second section which expressly recognizes the states’ power to deny “or in any way” abridge the right of their inhabitants to vote for “the members of the [state] legislature,” and its express provision of a remedy for such denial or abridgment. The comprehensive scope of the second section and its particular reference to the state legislatures preclude the suggestion that the first section was intended to have the result reached by the Court today. If indeed the words of the Fourteenth Amendment speak for themselves, as the majority’s disregard of history seems to imply, they speak as clearly as may be against the construction which the majority puts on them. But we are not limited to the language of the amendment itself.

The history of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment provides conclusive evidence that neither those who proposed nor those who ratified the amendment believed that the equal protection clause limited the power of the states to apportion their legislatures as they saw fit. Moreover, the history demonstrates that the intention to leave this power undisturbed was deliberate and was widely believed to be essential to the adoption of the amendment. . . .

In the House, Thaddeus Stevens5 introduced debate on the resolution on May 8, [1866]. . . .

He turned next to the second section, which he said he considered “the most important in the article.” Its effect, he said, was to fix “the basis of representation in Congress.” In unmistakable terms, he recognized the power of a state to withhold the right to vote:

If any state shall exclude any of her adult male citizens from the elective franchise, or abridge that right, she shall forfeit her right to representation in the same proportion. The effect of this provision will be either to compel the states to grant universal suffrage or so to shear them of their power as to keep them forever in a hopeless minority in the national government, both legislative and executive.

Closing his discussion of the second section, he noted his dislike for the fact that it allowed “the states to discriminate [with respect to the right to vote] among the same class, and receive proportionate credit in representation.”

Toward the end of the debate three days later, Mr. Bingham,6 the author of the first section in the Reconstruction Committee and its leading proponent, concluded his discussion of it with the following:

Allow me, Mr. Speaker, in passing, to say that this amendment takes from no State any right that ever pertained to it. No state ever had the right, under the forms of law or otherwise, to deny to any freeman the equal protection of the laws or to abridge the privileges or immunities of any citizen of the Republic, although many of them have assumed and exercised the power, and that without remedy. The amendment does not give, as the second section shows, the power to Congress of regulating suffrage in the several states.”…

In the three days of debate which separate the opening and closing remarks, both made by members of the Reconstruction Committee, every speaker on the resolution, with a single doubtful exception, assumed without question that, as Mr. Bingham said, “the second section excludes the conclusion that by the section suffrage is subjected to congressional law.”. . .

The facts recited above show beyond any possible doubt:

- that Congress, with full awareness of and attention to the possibility that the states would not afford full equality in voting rights to all their citizens, nevertheless deliberately chose not to interfere with the states’ plenary power in this regard when it proposed the Fourteenth Amendment;

- that Congress did not include in the Fourteenth Amendment restrictions on the states’ power to control voting rights because it believed that if such restrictions were included, the amendment would not be adopted; and

- that at least a substantial majority, if not all, of the states which ratified the Fourteenth Amendment did not consider that in so doing, they were accepting limitations on their freedom, never before questioned, to regulate voting rights as they chose. . . .

. . .In my judgment, today’s decisions are refuted by the language of the amendment which they construe and by the inference fairly to be drawn from subsequently enacted amendments. They are unequivocally refuted by history and by consistent theory and practice from the time of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment until today.

The Court’s elaboration of its new “constitutional” doctrine indicates how far—and how unwisely—it has strayed from the appropriate bounds of its authority. The consequence of today’s decision is that in all but the handful of states which may already satisfy the new requirements the local district court or, it may be, the state courts, are given blanket authority and the constitutional duty to supervise apportionment of the state legislatures. It is difficult to imagine a more intolerable and inappropriate interference by the judiciary with the independent legislatures of the states. . . .

. . . What is done today deepens my conviction that judicial entry into this realm is profoundly ill-advised and constitutionally impermissible. . . .I believe that the vitality of our political system, on which in the last analysis all else depends, is weakened by reliance on the judiciary for political reform; in time a complacent body politic may result.

These decisions also cut deeply into the fabric of our federalism. What must follow from them may eventually appear to be the product of state legislatures. Nevertheless, no thinking person can fail to recognize that the aftermath of these cases, however desirable it may be thought in itself, will have been achieved at the cost of a radical alteration in the relationship between the states and the federal government, more particularly the federal judiciary. Only one who has an overbearing impatience with the federal system and its political processes will believe that that cost was not too high or was inevitable.

Finally, these decisions give support to a current mistaken view of the Constitution and the constitutional function of this Court. This view, in a nutshell, is that every major social ill in this country can find its cure in some constitutional “principle,” and that this Court should “take the lead” in promoting reform when other branches of government fail to act. The Constitution is not a panacea for every blot upon the public welfare, nor should this Court, ordained as a judicial body, be thought of as a general haven for reform movements. The Constitution is an instrument of government, fundamental to which is the premise that in a diffusion of governmental authority lies the greatest promise that this nation will realize liberty for all its citizens. This Court, limited in function in accordance with that premise, does not serve its high purpose when it exceeds its authority, even to satisfy justified impatience with the slow workings of the political process. For when, in the name of constitutional interpretation, the Court adds something to the Constitution that was deliberately excluded from it, the Court in reality substitutes its view of what should be so for the amending process.

I dissent. . . .

- 1. A “white primary” was one in which only white voters were allowed to participate.

- 2. The cases under consideration.

- 3. Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939).

- 4. To remand a case is to return it to a lower court for reconsideration.

- 5. Thaddeus Stevens (1792–1868) was a Republican member of Congress from Pennsylvania and a leader of the Radical Republicans during Reconstruction.

- 6. John Bingham (1815–1900) was a Republican member of Congress from Ohio.

Civil Rights Act of 1964

July 02, 1964

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.