No related resources

Introduction

The Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war, yet the president is made commander in chief. For early Americans this meant that Congress alone held the power to authorize war, that is, to bring the nation from a state of peace to a state of war. For example, during the debate over the Neutrality Proclamation (Document 4), Alexander Hamilton defended George Washington’s power to declare that the nation was at peace, but he also went out of his way to say that only Congress could take the nation to war.

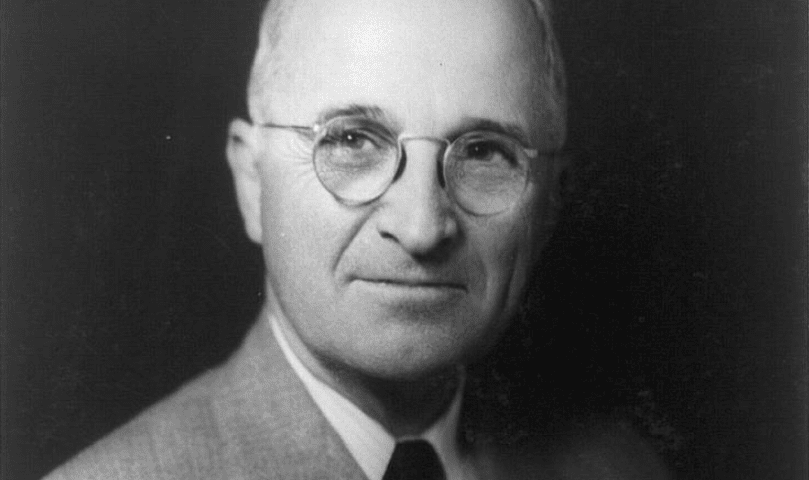

Since Harry Truman, however, presidents of both parties have assumed that it is the president who decides whether the nation will be at war. There are competing explanations for the emergence of this new understanding of the war power. One is that the United Nations provides a new and competing source of authority for military action. Another is that Cold War and the reality of atomic weapons rendered Congress’s role less important. A third explanation is that wielding the war power is politically costly, so risk-adverse members of Congress are happy to let the president have it.

In the selection below, Truman announces his actions in Korea. Notice the role he assumes for the United Nations and the limited role he assumes for Congress.

Source: Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States. Harry S. Truman. Containing the Public Messages, Speeches, and Statements of the President, 1950 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1965), 527-37.

To the Congress of the United States:

I am reporting to the Congress on the situation which has been created in Korea, and on the actions which this Nation has taken, as a member of the United Nations, to meet this situation. I am also laying before the Congress my views concerning the significance of these events for this Nation and the world, and certain recommendations for legislative action which I believe should be taken at this time.

At four o’clock in the morning, Sunday, June 25th, Korean time, armed forces from north of the thirty-eighth parallel invaded the Republic of Korea. . . .

This outright breach of the peace, in violation of the United Nations Charter, created a real and present danger to the security of every nation. This attack was, in addition, a demonstration of contempt for the United Nations, since it was an attempt to settle, by military aggression, a question which the United Nations had been working to settle by peaceful means.

The attack on the Republic of Korea, therefore, was a clear challenge to the basic principles of the United Nations Charter and to the specific actions taken by the United Nations in Korea. If this challenge had not been met squarely, the effectiveness of the United Nations would have been all but ended, and the hope of mankind that the United Nations would develop into an institution of world order would have been shattered.

Prompt action was imperative. The Security Council of the United Nations met, at the request of the United States, in New York at two o’clock in the afternoon, Sunday, June 25th, eastern daylight time. Since there is a 14-hour difference in time between Korea and New York, this meant that the Council convened just 24 hours after the attack began.

At this meeting, the Security Council passed a resolution which called for the immediate cessation of hostilities and for the withdrawal of the invading troops to the thirty-eighth parallel, and which requested the members of the United Nations to refrain from giving aid to the northern aggressors and to assist in the execution of this resolution. The representative of the Soviet Union to the Security Council stayed away from the meetings, and the Soviet Government has refused to support the Council’s resolution.

The attack launched on June 25th moved ahead rapidly. The tactical surprise gained by the aggressors, and their superiority in planes, tanks and artillery, forced the lightly-armed defenders to retreat. The speed, the scale, and the coordination of the attack left no doubt that it had been plotted long in advance.

When the attack came, our Ambassador to Korea, John J. Muccio, began the immediate evacuation of American women and children from the danger zone. To protect this evacuation, air cover and sea cover were provided by the Commander in Chief of United States Forces in the Far East, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur.[1] In response to urgent appeals from the Government of Korea, General MacArthur was immediately authorized to send supplies of ammunition to the Korean defenders. These supplies were sent by air transport, with fighter protection. The United States Seventh Fleet was ordered north from the Philippines, so that it might be available in the area in case of need.

Throughout Monday, June 26th, the invaders continued their attack with no heed to the resolution of the Security Council of the United Nations. Accordingly, in order to support the resolution, and on the unanimous advice of our civil and military authorities, I ordered United States air and sea forces to give the Korean Government troops cover and support.

On Tuesday, June 27th, when the United Nations Commission in Korea had reported that the northern troops had neither ceased hostilities nor withdrawn to the thirty-eighth parallel, the United Nations Security Council met again and passed a second resolution recommending that members of the United Nations furnish to the Republic of Korea such aid as might be necessary to repel the attack and to restore international peace and security in the area. The representative of the Soviet Union to the Security Council stayed away from this meeting also, and the Soviet Government has refused to support the Council’s resolution.

The vigorous and unhesitating actions of the United Nations and the United States in the face of this aggression met with an immediate and overwhelming response throughout the free world. The first blow of aggression had brought dismay and anxiety to the hearts of men the world over. The fateful events of the 1930’s, when aggression unopposed bred more aggression and eventually war, were fresh in our memory.

But the free nations had learned the lesson of history. Their determined and united actions uplifted the spirit of free men everywhere. As a result, where there had been dismay there is hope; where there had been anxiety there is firm determination.

Fifty-two of the fifty-nine member nations have supported the United Nations action to restore peace in Korea.

A number of member nations have offered military support or other types of assistance for the United Nations action to repel the aggressors in Korea. In a third resolution, passed on July 7th, the Security Council requested the United States to designate a commander for all the forces of the members of the United Nations in the Korean operation, and authorized these forces to fly the United Nations flag. In response to this resolution, General MacArthur has been designated as commander of these forces. These are important steps forward in the development of a United Nations system of collective security. Already, aircraft of two nations – Australia and Great Britain – and naval vessels of five nations – Australia, Canada, Great Britain, the Netherlands and New Zealand – have been made available for operations in the Korean area, along with forces of Korea and the United States, under General MacArthur’s command. The other offers of assistance that have been and will continue to be made will be coordinated by the United Nations and by the unified command, in order to support the effort in Korea to maximum advantage.

All the members of the United Nations who have indorsed the action of the Security Council realize the significance of the step that has been taken. This united and resolute action to put down lawless aggression is a milestone toward the establishment of a rule of law among nations.

Only a few countries have failed to support the common action to restore the peace. The most important of these is the Soviet Union.

Since the Soviet representative had refused to participate in the meetings of the Security Council which took action regarding Korea, the United States brought the matter directly to the attention of the Soviet Government in Moscow. On June 27th, we requested the Soviet Government, in view of its known close relations with the north Korean regime, to use its influence to have the invaders withdraw at once.

The Soviet Government, in its reply on June 29th and in subsequent statements, has taken the position that the attack launched by the north Korean forces was provoked by the Republic of Korea, and that the actions of the United Nations Security Council were illegal.

These Soviet claims are flatly disproved by the facts.

The attitude of the Soviet Government toward the aggression against the Republic of Korea, is in direct contradiction to its often-expressed intention to work with other nations to achieve peace in the world.

For our part, we shall continue to support the United Nations action to restore peace in the Korean area.

As the situation has developed, I have authorized a number of measures to be taken. Within the first week of the fighting, General MacArthur reported, after a visit to the front, that the forces from north Korea were continuing to drive south, and further support to the Republic of Korea was needed. Accordingly, General MacArthur was authorized to use United States Army troops in Korea, and to use United States aircraft of the Air Force and the Navy to conduct missions against specific military targets in Korea north of the thirty-eighth parallel, where necessary to carry out the United Nations resolution. General MacArthur was also directed to blockade the Korean coast.

The attacking forces from the north have continued to move forward, although their advance has been slowed down. The troops of the Republic of Korea, though initially overwhelmed by the tanks and artillery of the surprise attack by the invaders, have been reorganized and are fighting bravely.

United States forces, as they have arrived in the area, have fought with great valor. The Army troops have been conducting a very difficult delaying operation with skill and determination, outnumbered many times over by attacking troops, spearheaded by tanks. Despite the bad weather of the rainy season, our troops have been valiantly supported by the air and naval forces of both the United States and other members of the United Nations.

In this connection, I think it is important that the nature of our military action in Korea be understood. It should be made perfectly clear that the action was undertaken as a matter of basic moral principle. The United States was going to the aid of a nation established and supported by the United Nations and unjustifiably attacked by an aggressor force. . . .

In these circumstances, we must take action to ensure that the increased national defense needs will be met, and that in the process we do not bring on an inflation, with its resulting hardship for every family.

At the same time, we must recognize that it will be necessary for a number of years to support continuing defense expenditures, including assistance to other nations, at a higher level than we had previously planned. Therefore, the economic measures we take now must be planned and used in such a manner as to develop and maintain our economic strength for the long run as well as the short run.

I am recommending certain legislative measures to help achieve these objectives. I believe that each of them should be promptly enacted. We must be sure to take the steps that are necessary now, or we shall surely be required to take much more drastic steps later on.

First, we should adopt such direct measures as are now necessary to assure prompt and adequate supplies of goods for military and essential civilian use. I therefore recommend that the Congress now enact legislation authorizing the Government to establish priorities and allocate materials as necessary to promote the national security; to limit the use of materials for nonessential purposes; to prevent inventory hoarding; and to requisition supplies and materials needed for the national defense, particularly excessive and unnecessary inventories.

Second, we must promptly adopt some general measures to compensate for the growth of demand caused by the expansion of military programs in a period of high civilian incomes. I am directing all executive agencies to conduct a detailed review of Government programs, for the purpose of modifying them wherever practicable to lessen the demand upon services, commodities, raw materials, manpower, and facilities which are in competition with those needed for national defense. The Government, as well as the public, must exercise great restraint in the use of those goods and services which are needed for our increased defense efforts.

Nevertheless, the increased appropriations for the Department of Defense, plus the defense-related appropriations which I have recently submitted for power development and atomic energy, and others which will be necessary for such purposes as stockpiling, will mean sharply increased Federal expenditures. . . .

The free world has made it clear, through the United Nations, that lawless aggression will be met with force. This is the significance of Korea – and it is a significance whose importance cannot be over-estimated.

I shall not attempt to predict the course of events. But I am sure that those who have it in their power to unleash or withhold acts of armed aggression must realize that new recourse to aggression in the world today might well strain to the breaking point the fabric of world peace.

The United States can be proud of the part it has played in the United Nations action in this crisis. We can be proud of the unhesitating support of the American people for the resolute actions taken to halt the aggression in Korea and to support the cause of world peace.

The Congress of the United States, by its strong, bi-partisan support of the steps we are taking and by repeated actions in support of international cooperation, has contributed most vitally to the cause of peace. The expressions of support which have been forthcoming from the leaders of both political parties for the actions of our Government and of the United Nations in dealing with the present crisis, have buttressed the firm morale of the entire free world in the face of this challenge.

The American people, together with other free peoples, seek a new era in world affairs. We seek a world where all men may live in peace and freedom, with steadily improving living conditions, under governments of their own free choice.

For ourselves, we seek no territory or domination over others. We are determined to maintain our democratic institutions so that Americans now and in the future can enjoy personal liberty, economic opportunity, and political equality. We are concerned with advancing our prosperity and our well-being as a Nation, but we know that our future is inseparably joined with the future of other free peoples.

We will follow the course we have chosen with courage and with faith, because we carry in our hearts the flame of freedom. We are fighting for liberty and for peace – and with God’s blessing we shall succeed.

HARRY S. TRUMAN

- 1. Douglas MacArthur (1880–1964), was Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in post war Japan. He was removed from his command by Truman in 1951, after publicly disagreeing with the Truman Administration over the direction of the war effort in Korea.

The Internal Security Act

October 20, 1950

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.