No study questions

No related resources

‘–excerpts–

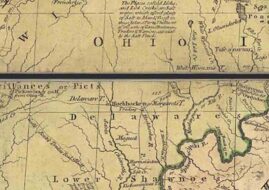

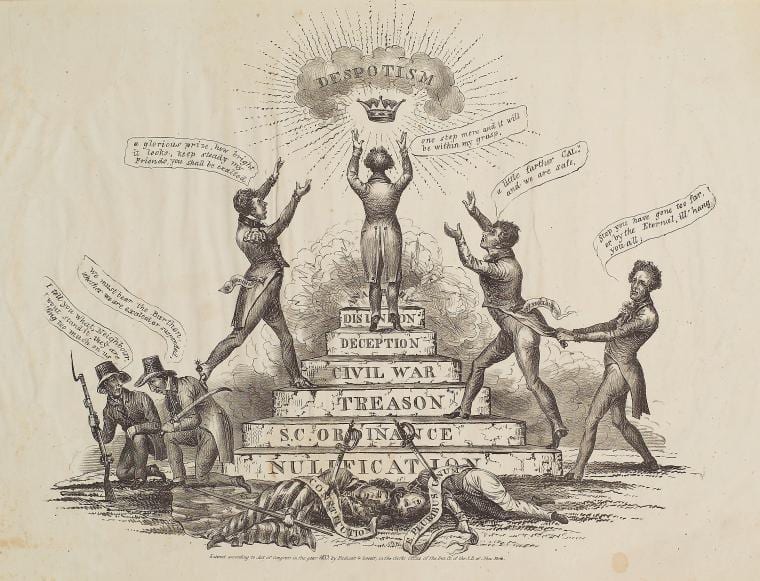

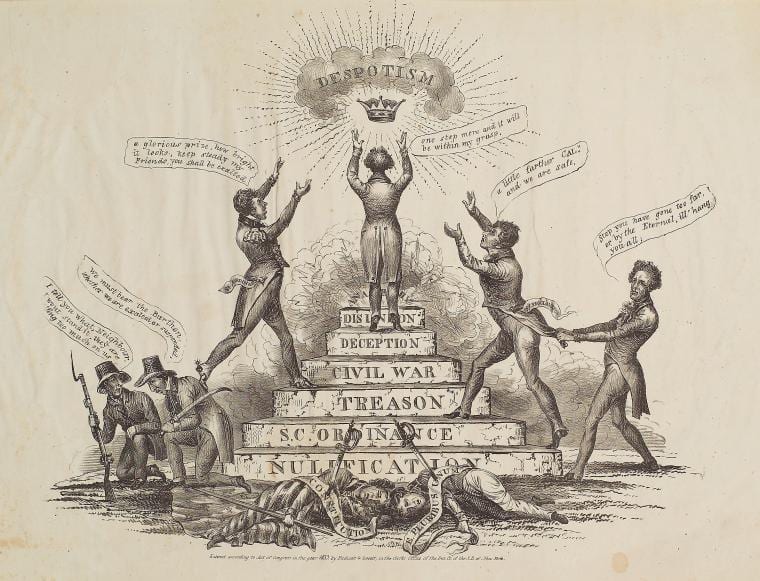

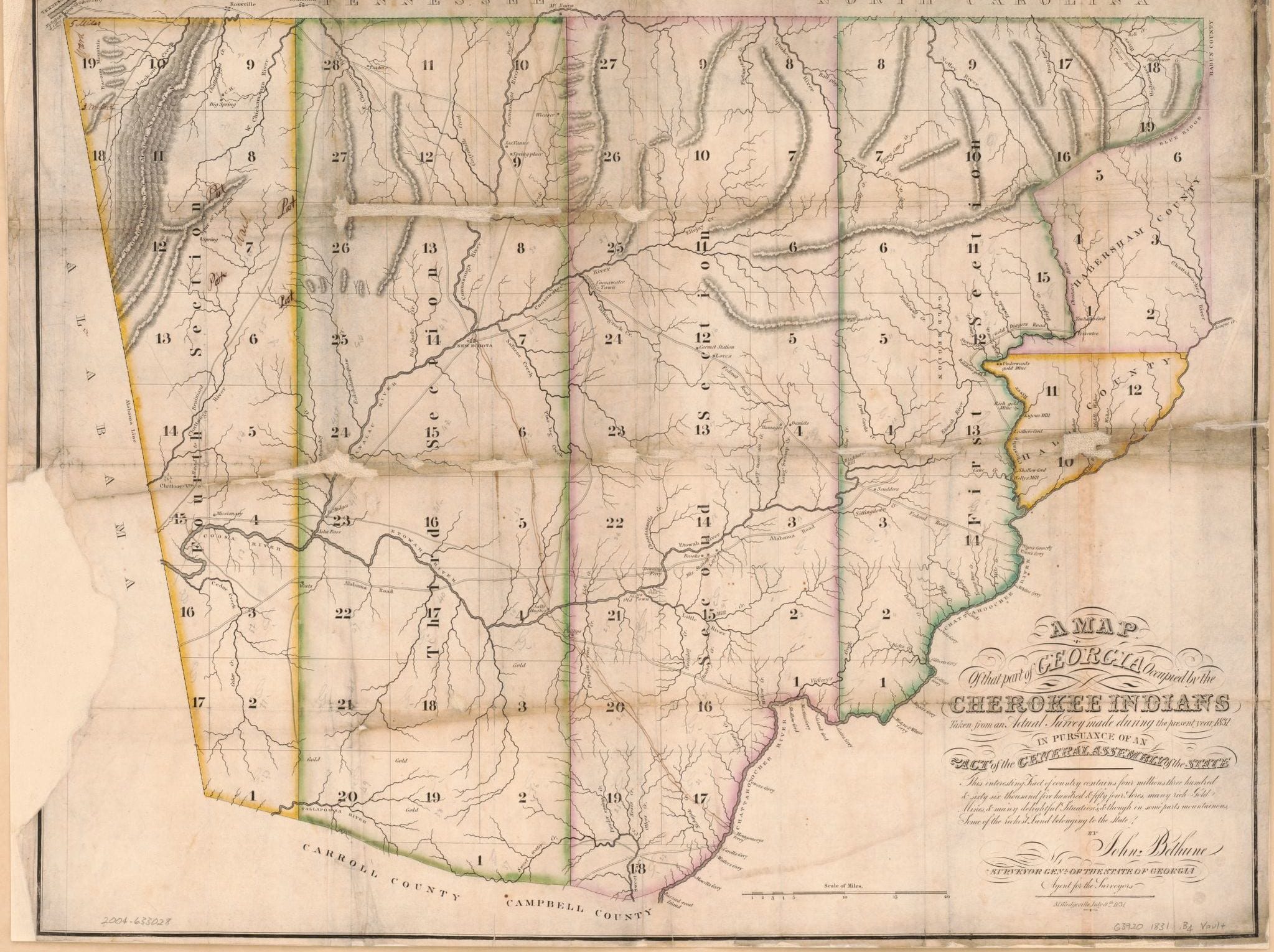

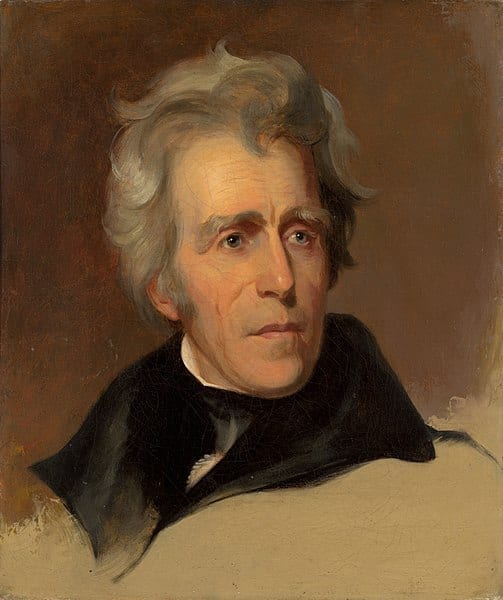

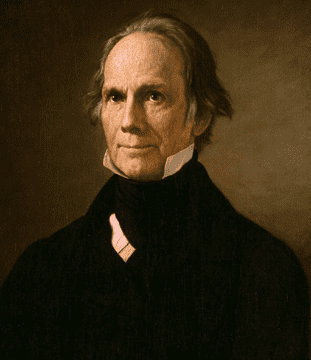

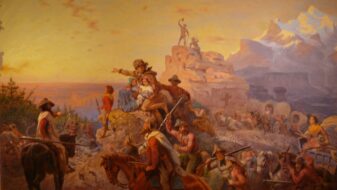

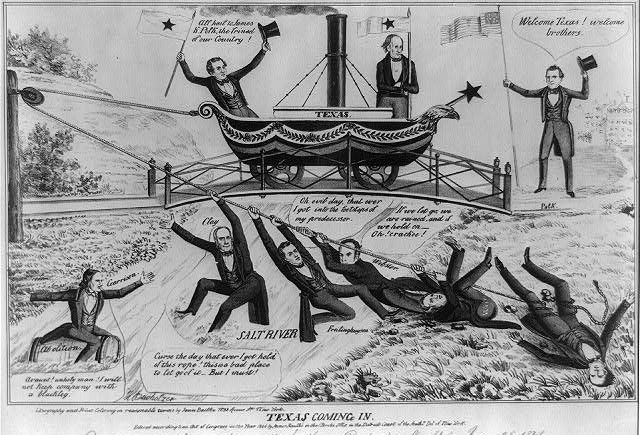

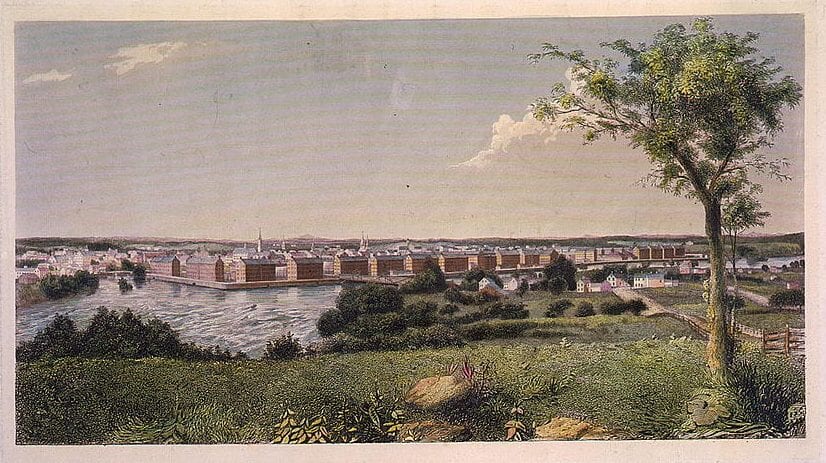

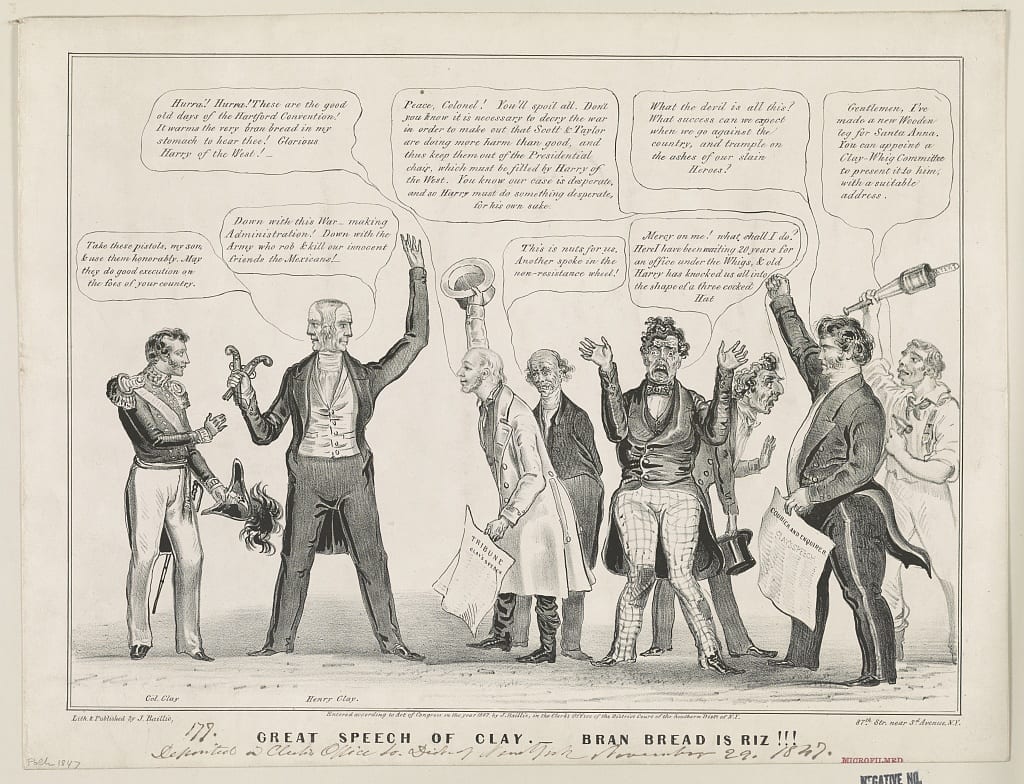

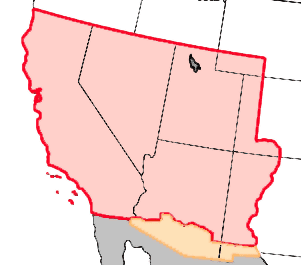

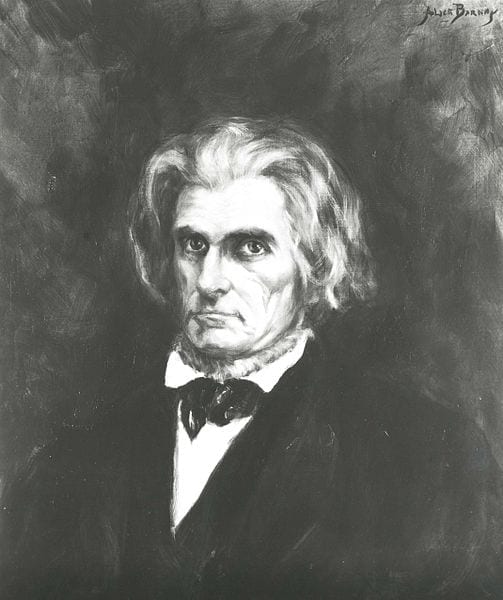

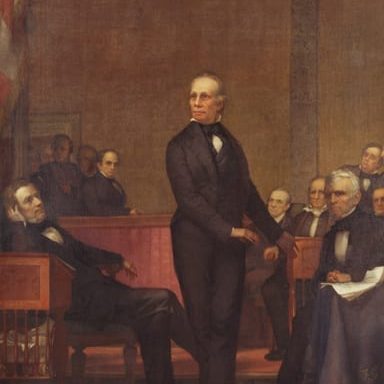

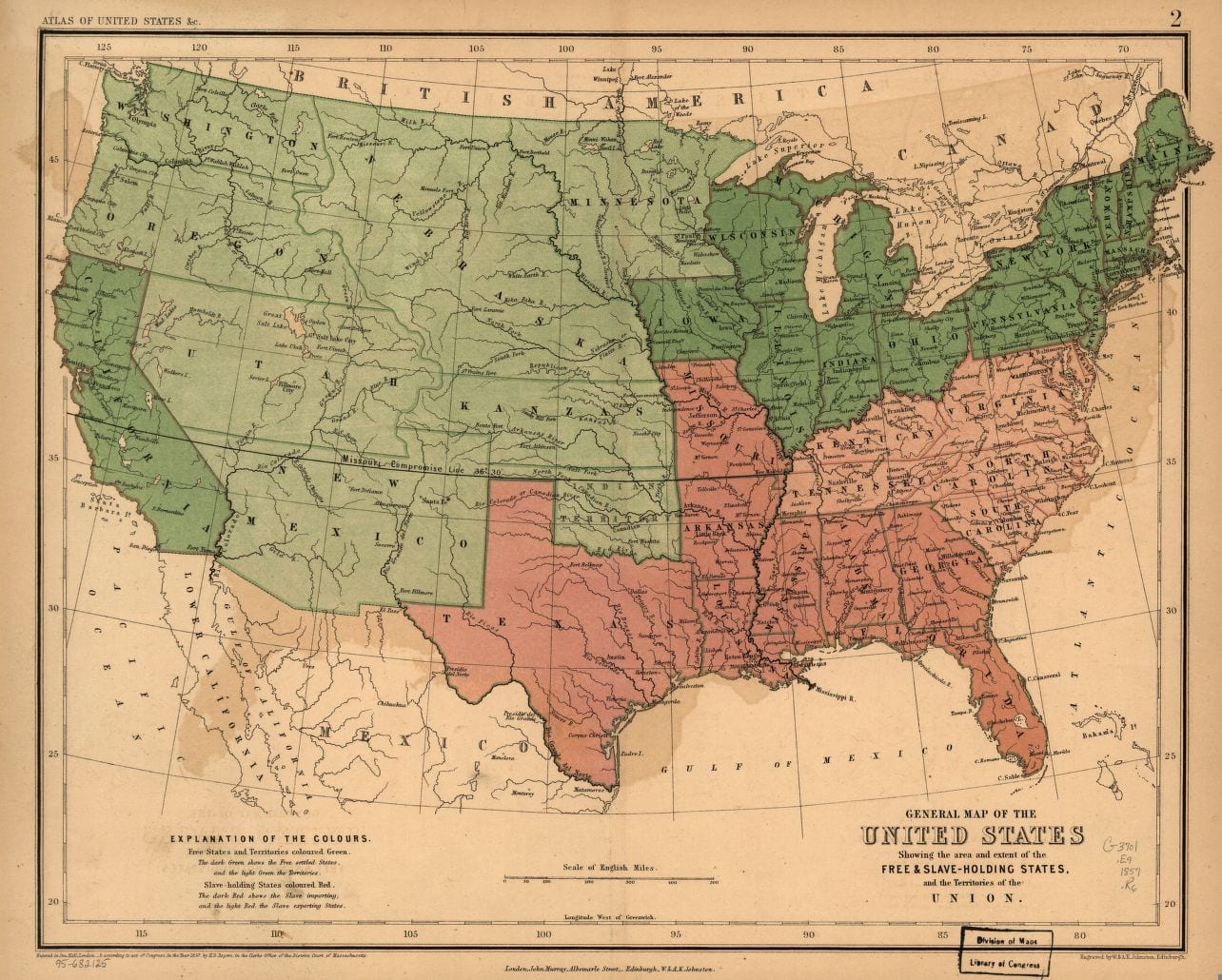

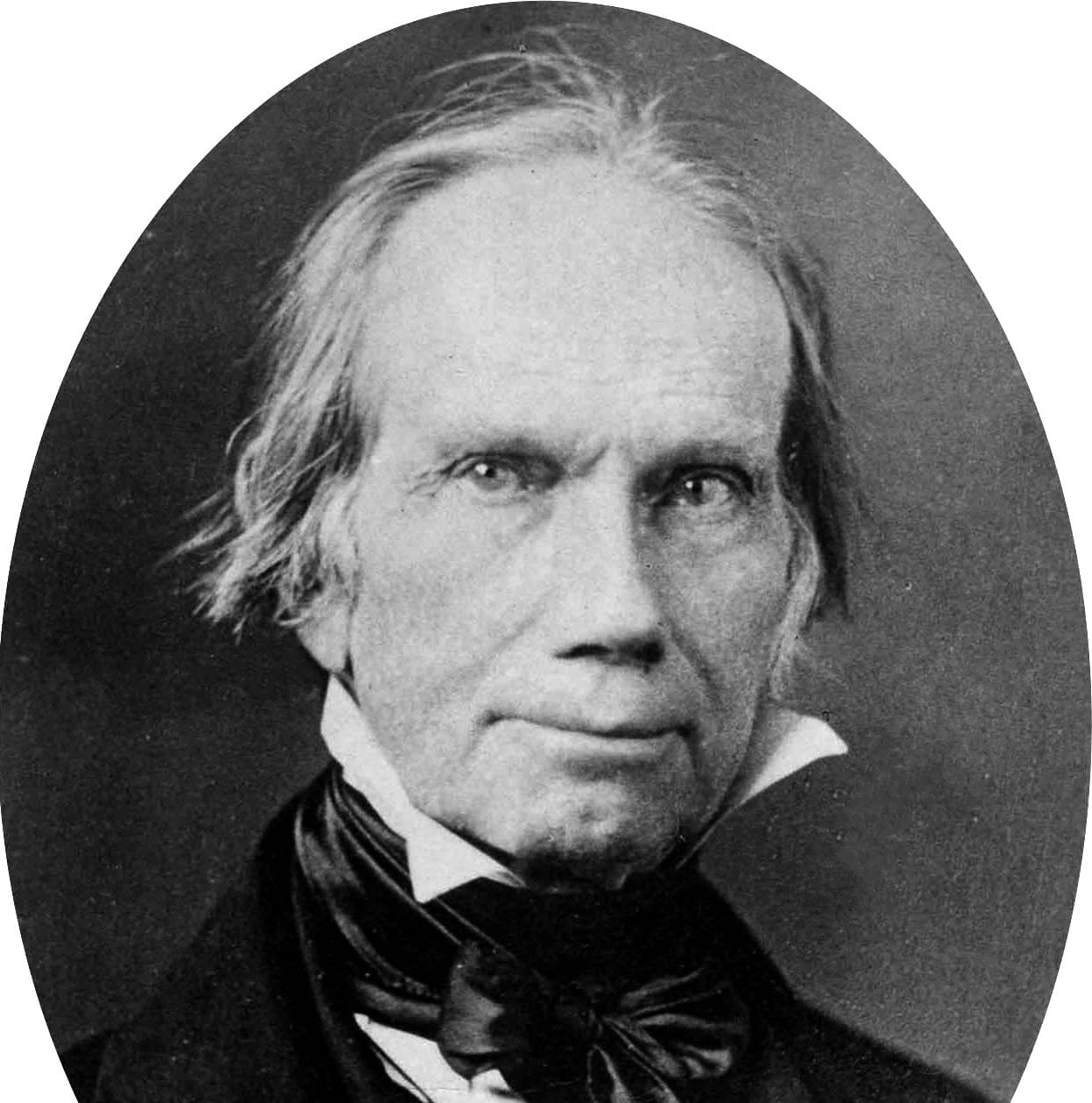

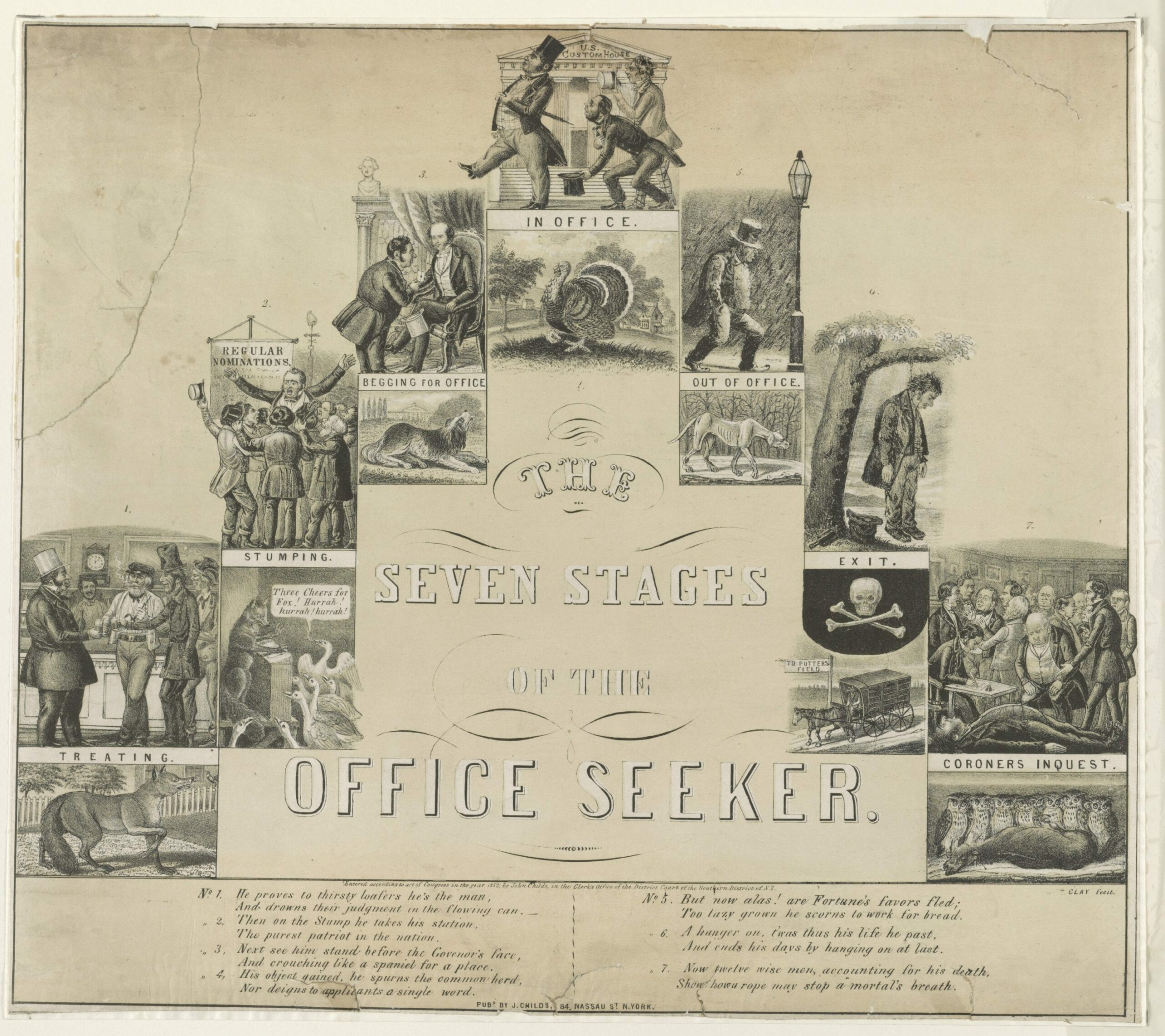

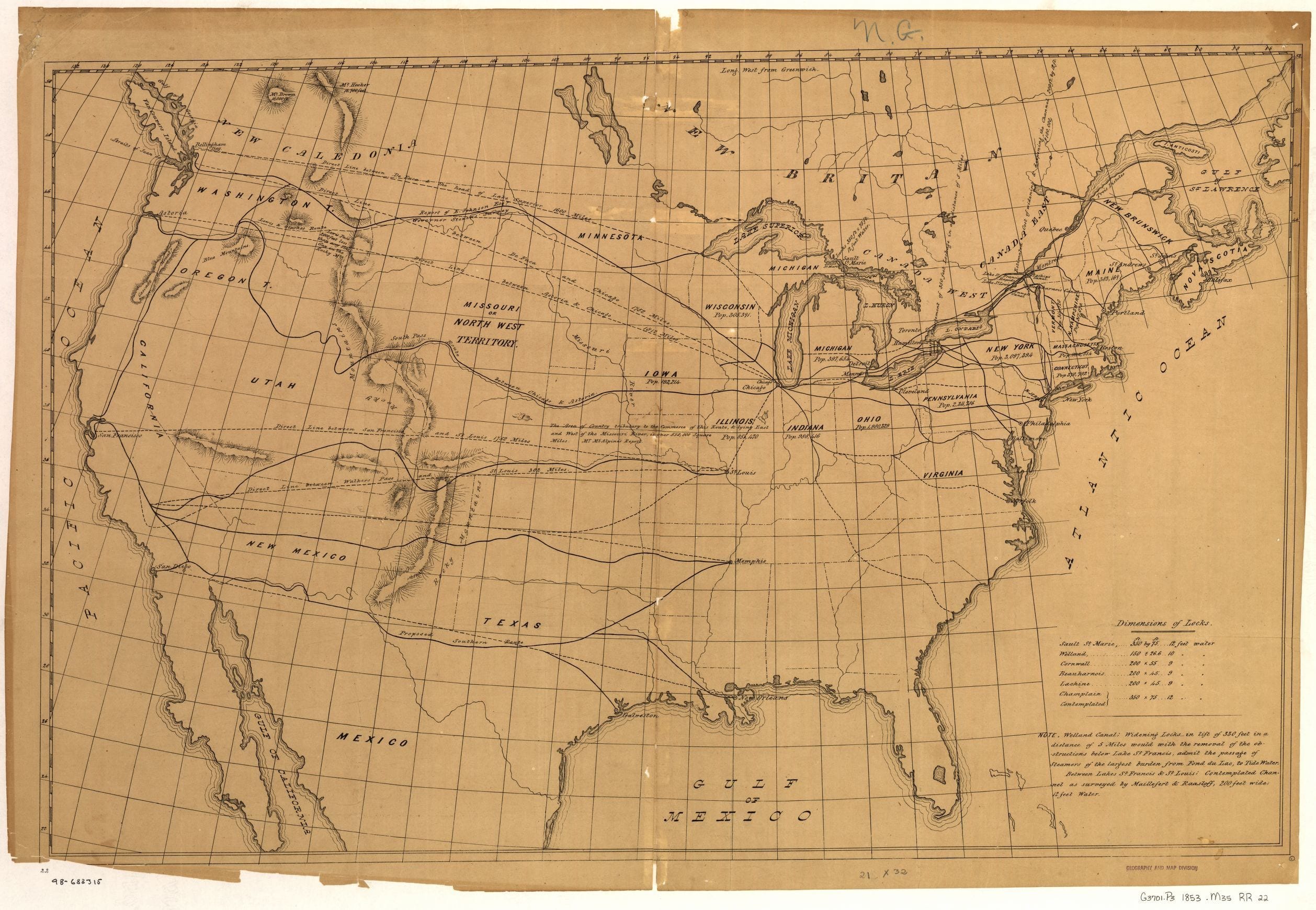

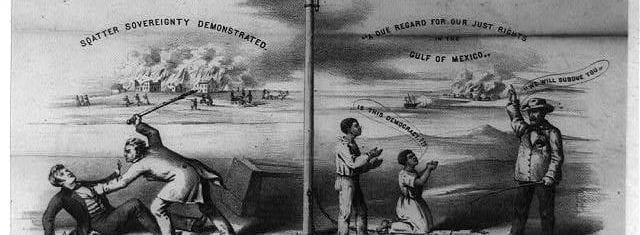

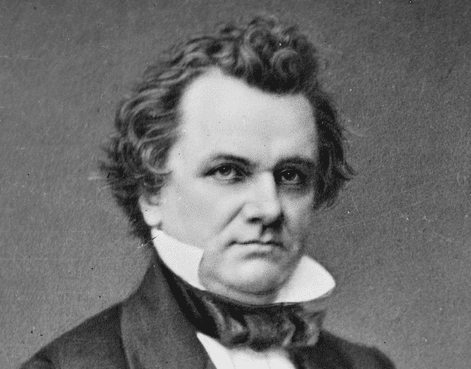

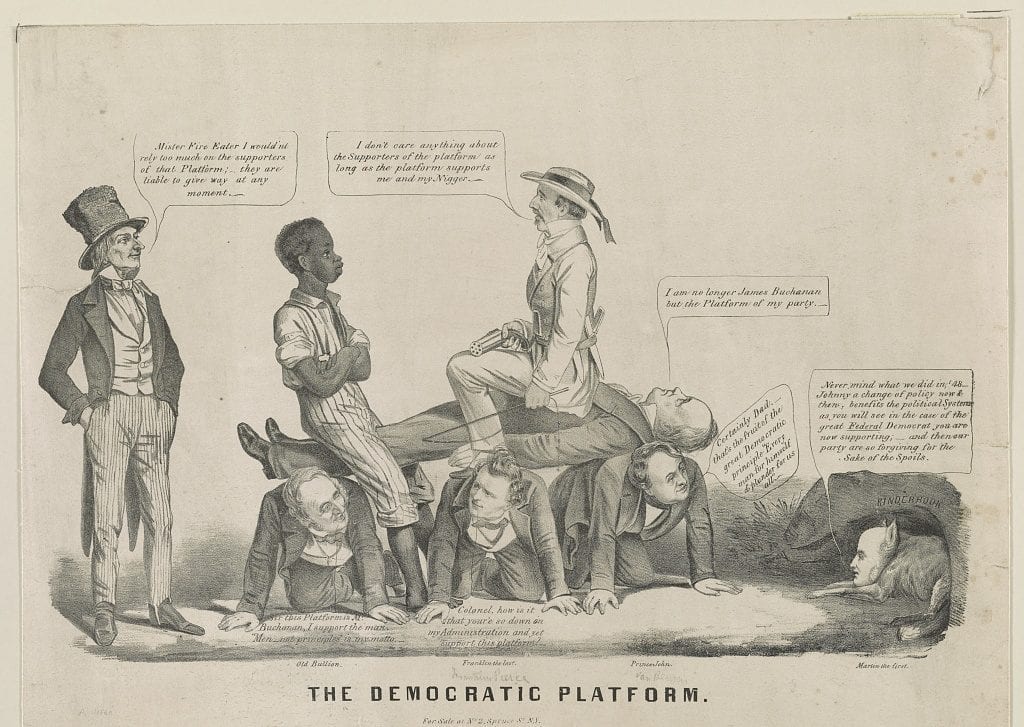

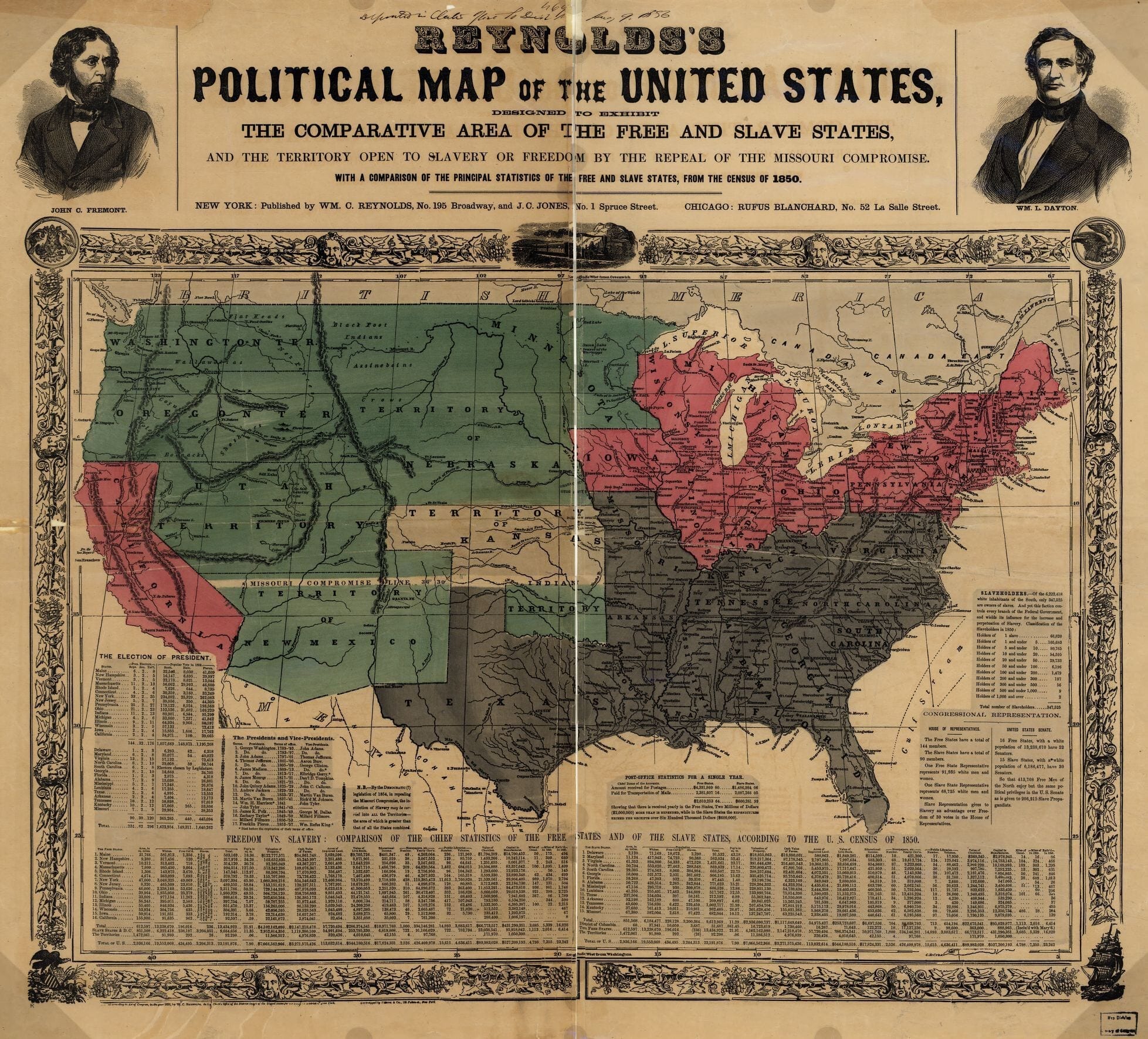

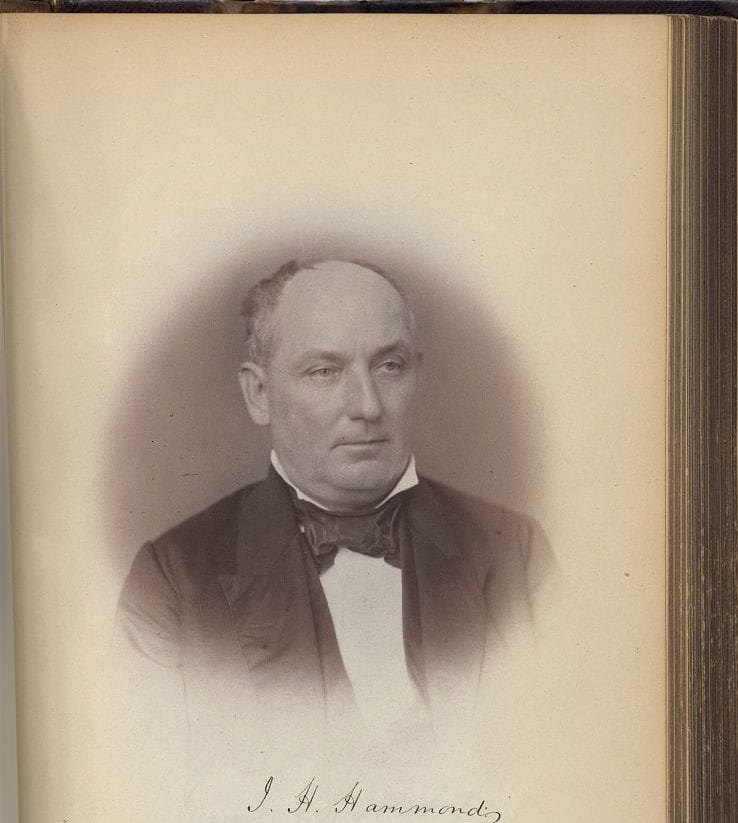

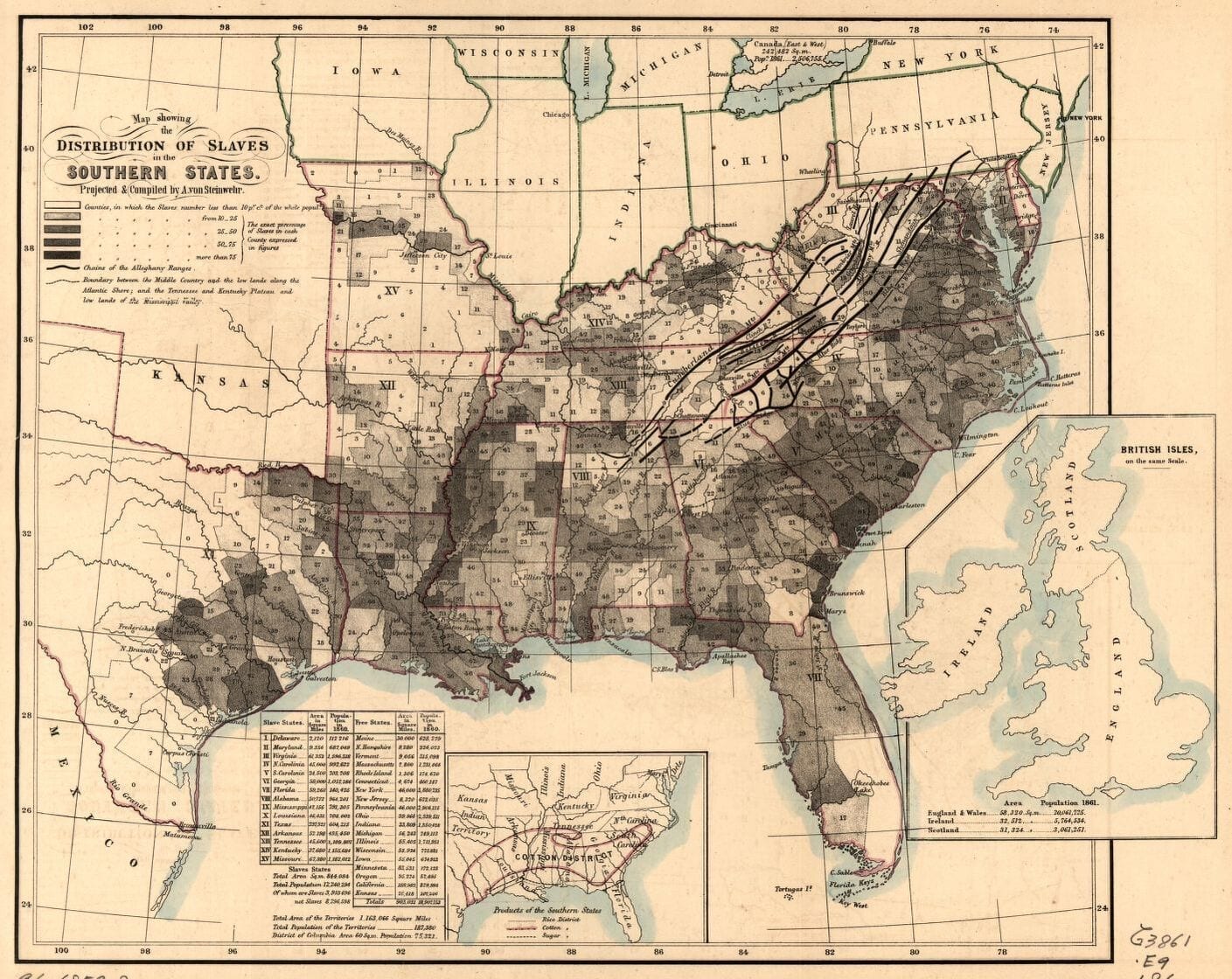

Mr. President [of the Senate], I approach now to the question of what the consequences must be of the defeat of the measure now before the Senate, and what the consequence will probably be in case of the successful support of the measure by Congress. If the bill is defeated, and no equivalent measure be passed, as in all human probability will be the case — if this measure is not passed, and we go home, in what condition do we leave this free and glorious people?… If there should be a war, even of all the southern States with the residue of the Union itself, the residue of the Union, might not prove an overmatch for southern resistance. I will not assert what party would prevail in such a context; for you know, sir, what all history teaches, that the end of war is never seen in the beginning of war, and that few wars which mankind have waged among themselves, have ever terminated in the accomplishment of the objects for which they were commenced. There are two descriptions of ties which bind this Union and this glorious people together. One is the political bond and tie which connects them, and the other is the fraternal commercial tie which binds them together. I want to see them both preserved. I wish never to see the day when the ties of commerce and fraternity shall be destroyed, and the iron bands afforded by political connections shall alone exist and keep us together. And when you take into view the firm conviction which Texas has of her undoubted right; when we know at this moment that her Legislature is about to convene, and before the autumn arrives, troops may be on their march from Texas to take possession of the disputed Territory of New Mexico, which she believes to belong to herself– is there not danger which should make us pause and reflect, before we leave this capitol without providing against such a perilous emergency? Let blood be once spilled in the conflict between the troops of Texas and those of the United States, and my word for it, thousands of gallant men will fly from the States which I have enumerated, if not from all the slaveholding States, to sustain and succor the power of Texas, and to preserve her in possession of that in which they, as well as she, feel so deep an interest. Even from Missouri — because her valiant population might most quickly pour down upon Santa Fé aid and assistance to Texas — even from Missouri, herself a slave State, it is not at all unlikely that thousands might flock to the standard of the weaker party, and assist Texas in her struggles. Is that a state of things which you, senators, can contemplate without apprehension? Or can you content yourselves with going home, and leaving it to be possibly realized before the termination of the current year? Are you not bound, as men, as patriots, as enlightened statesmen, to provide for the contingency? And how can you provide for it better then by this bill, which separates a reluctant people about to be united to Texas , a people who, themselves, perhaps, will raise the standard of resistance against the power of Texas — separates them from Texas, and guards against the possibility of a sympathetic and contagious war, springing up between the slave States and the power of the general government, which I regard as almost inevitable, if Congress adjourns with the admission of California alone, stopping there, and doing nothing else. For, sir the admission of California alone, under all circumstances of the time, with the proviso still suspended over the heads of the South, with the abolition of slavery still threatened in the District of Columbia — the act of the admission of California, without provision for the settlement of the Texas boundary question, without the other potions of this bill, will aggravate, and embitter, and enrage the South, and make them rush on furiously and blindly, animated, as they believe, by a patriotic zeal to defend themselves against northern aggression. I call upon you, then, and I call upon the Senate, in the name of the country, never to separate from this capitol, without settling all these questions, leaving nothing to disturb the general peace and repose of the country…

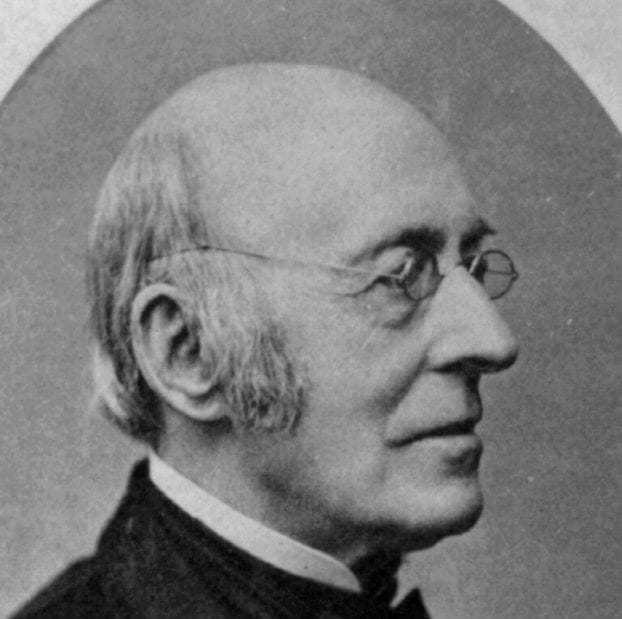

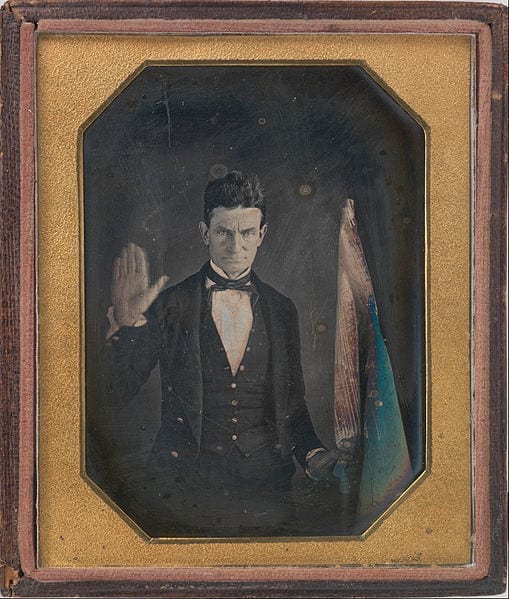

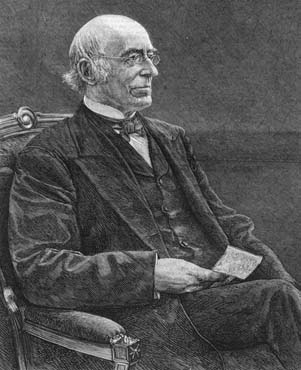

…There is not an abolitionist in the United States that I know of — there may be some — there is not an abolition press, if you begin with the abolition press located at Washington, and embrace all others, that is not opposed to this bill — not one of them. There is not an abolitionist in this Senate chamber or out of it, anywhere, that is not opposed to the adoption of this compromise plan. And why are they opposed to it? They see their doom as certain as there is a God in heaven who sends His providential dispensations to calm the threatening storm and to tranquillize agitated man. As certain as that God exists in heaven, your business [turning toward Mr. Hale], your vocation is gone. I argue much more from acts, from instinctive feelings, from the promptings of the heart, from a conscious apprehension of impending ruin to the cause which they espouse, than I do from the declamatory and eloquent language which they employ in resistance to this measure. What! increased agitation, and the agitators against the plan. It is an absurdity…

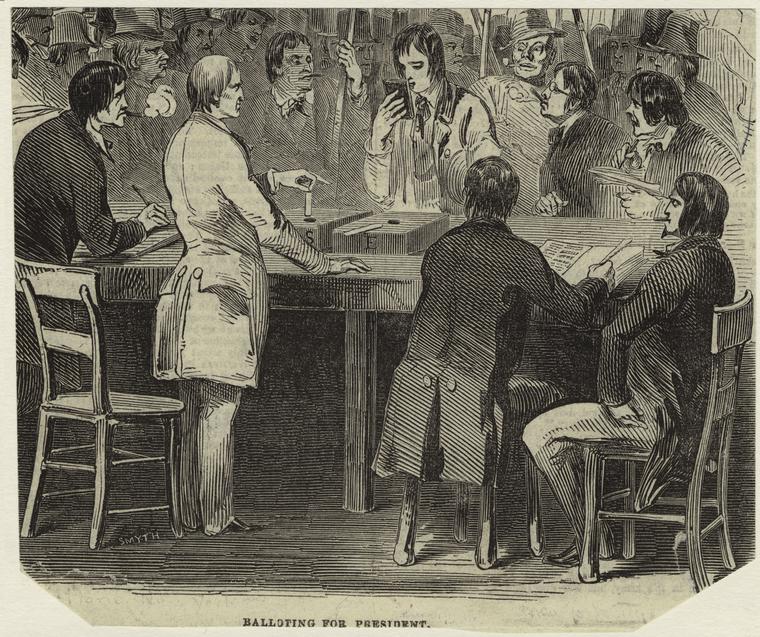

But, Mr. President, I am not only fortified on my convictions that this will be the salutary and healing effect of this great plan of compromise and settlement of our difficulties, but I am supported by the nature of man and the truth of history. What is that nature? Why, sir, after perturbing storms a calm is sure to follow. The nation wants repose. It pants for repose, and entreats you to give it peace and tranquillity. Do you believe, that when the nation’s senators and the nation’s representatives, after such a continued struggle, as we have had, shall settle these questions, it is possible for the most malignant of all men longer to disturb the peace, and quiet, and harmony of this otherwise most prosperous country? But, I said, not only according to the nature of man, but according to the universal desire which prevails throughout the wide-spread land, would the acceptance of this measure, in my opinion, lead to a joy and exultation almost unexampled in our history. I refer to historical instances occurring in our government to verify me in the conviction I entertain of the healing and tranquillizing consequences which would result from the adoption of this measure. What was said when the compromise was passed? Then, as now, it was denounced. Then, as now, when it was approaching its passage, when being perfected, it was said, “It will not quell the storm, nor give peace to the country.” How was it received when it passed? The bells rang, the cannons were fired, and every demonstration of joy throughout the whole land was made upon the settlement by the Missouri compromise… But now, more than then, has this agitation been increased. Now, more than then, are the dangers which exist, if the controversy remains unsettled, more aggravated and more to be dreaded. The idea of disunion then was scarcely a low whisper. Now, it has become a familiar language in certain portions of the country. The public mind and the public heart are becoming familiarized with that most dangerous and fatal of all events, the disunion of the States. People begin to contend that this is not so bad a thing as they supposed. Like the progress in all human affairs, as we approach danger it disappears, it diminishes in our conception, and we no longer regard it with that awful apprehension of consequences that we did before we came into contact with it. Everywhere now there is a state of things, a degree of alarm and apprehension, and determination to fight, as they regard it, against the aggressions of the North. That did not so demonstrate itself at the period of the Missouri compromise. It was followed, in consequence of the adoption of the measure which settled the difficulty of Missouri, by peace, harmony, and tranquility. So now, I infer from the greater amount of agitation, from the greater amount of danger, that, if you adopt the measures under consideration, they, too, will be followed by the same amount of contentment, satisfaction, peace, and tranquility which ensued after the Missouri compromise…

I believe from the bottom of my soul, that the measure is the re-union of this Union. I believe that it is the dove of peace, which, taking its aerial flight from the dome of the capitol, carries the glad tidings of assured peace and restored harmony to all the remotest extremities of this distracted land. I believe that it will be attended with all those beneficent effects. And now let us discard all resentment, all passions, all petty jealousies, all personal desires, all love of place, all hungering after the gilded crumbs which fall from the table of power. Let us forget popular fears, from whatever quarter they may spring. Let us go to the limpid fountain of unadulterated patriotism, and think alone of our God, our country, our consciences, and our glorious Union; that Union without which we shall be torn into hostile fragments, and sooner or later become the victims of military despotism, or foreign domination…

Let me, Mr. President, in conclusion, say that the most disastrous consequences would occur, in my opinion, were we to go home, doing nothing to satisfy and tranquillize the country upon these great questions. What will be the judgment of mankind, what the judgment of that portion of mankind who are looking upon the progress of this scheme of self-government as being that which holds out the highest hopes and expectations of ameliorating the condition of mankind — what will their judgment be? Will not all the monarchs of the old world pronounce our glorious republic a disgraceful failure? What will be the judgment of our constituent, when we return to them and they ask us, How have you left your country? Is all quiet — and happy — are all the seeds of distraction or division crushed and dissipated? And, sir, when you come into the bosom of your family, when you come to converse with the partner of your fortunes, of your happiness, and of your sorrows, and when in the midst of the common offspring of both of you, she asks you, “Is there any danger of civil war? Is there any danger of the torch being applied to any portion of the country? Have you settled the questions which you have been so long discussing and deliberating upon at Washington? Is all peace and quiet?” What response, Mr. President, can you make to that wife of your choice, and those children with whom you have been blessed by God? Will you go home and leave all in disorder and confusion, all unsettled, all open? The contentions and agitations of the past will be increased and augmented by the agitations resulting from our neglect to decide them. Sir, we shall stand condemned by all human judgment below, and of that above it is not for me to speak. We shall stand condemned in our own consciences, by our own constituents, and by our own country… These are my sentiments — make the most of them. [Speech continues.]

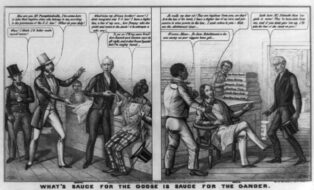

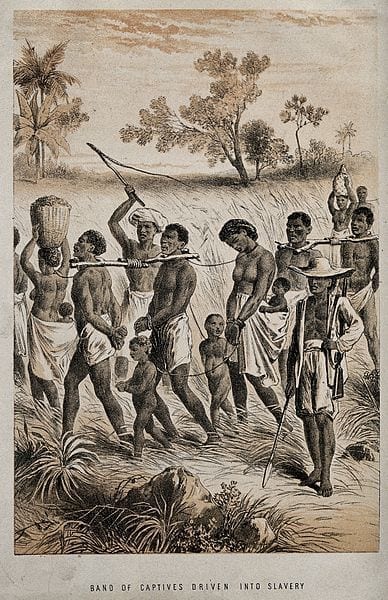

Fugitive Slave Act 1850

September 18, 1850

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.