Introduction

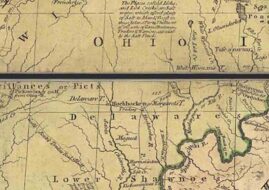

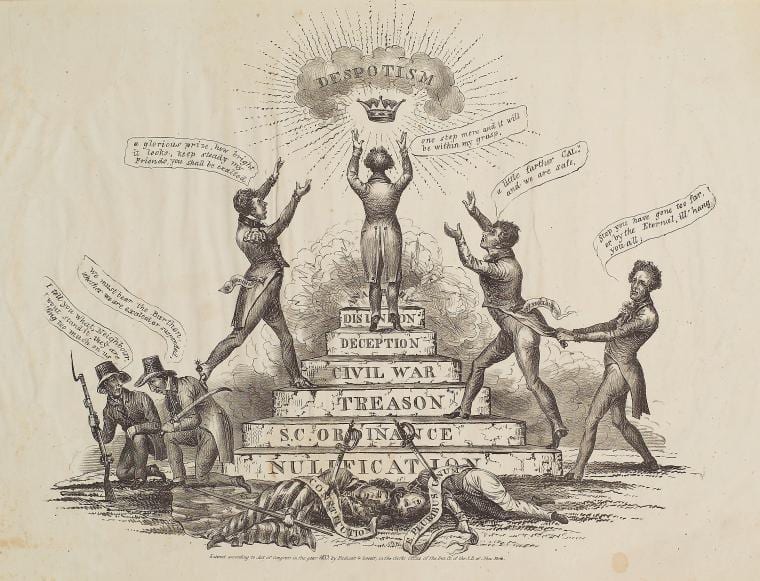

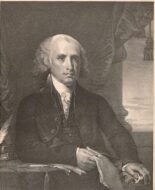

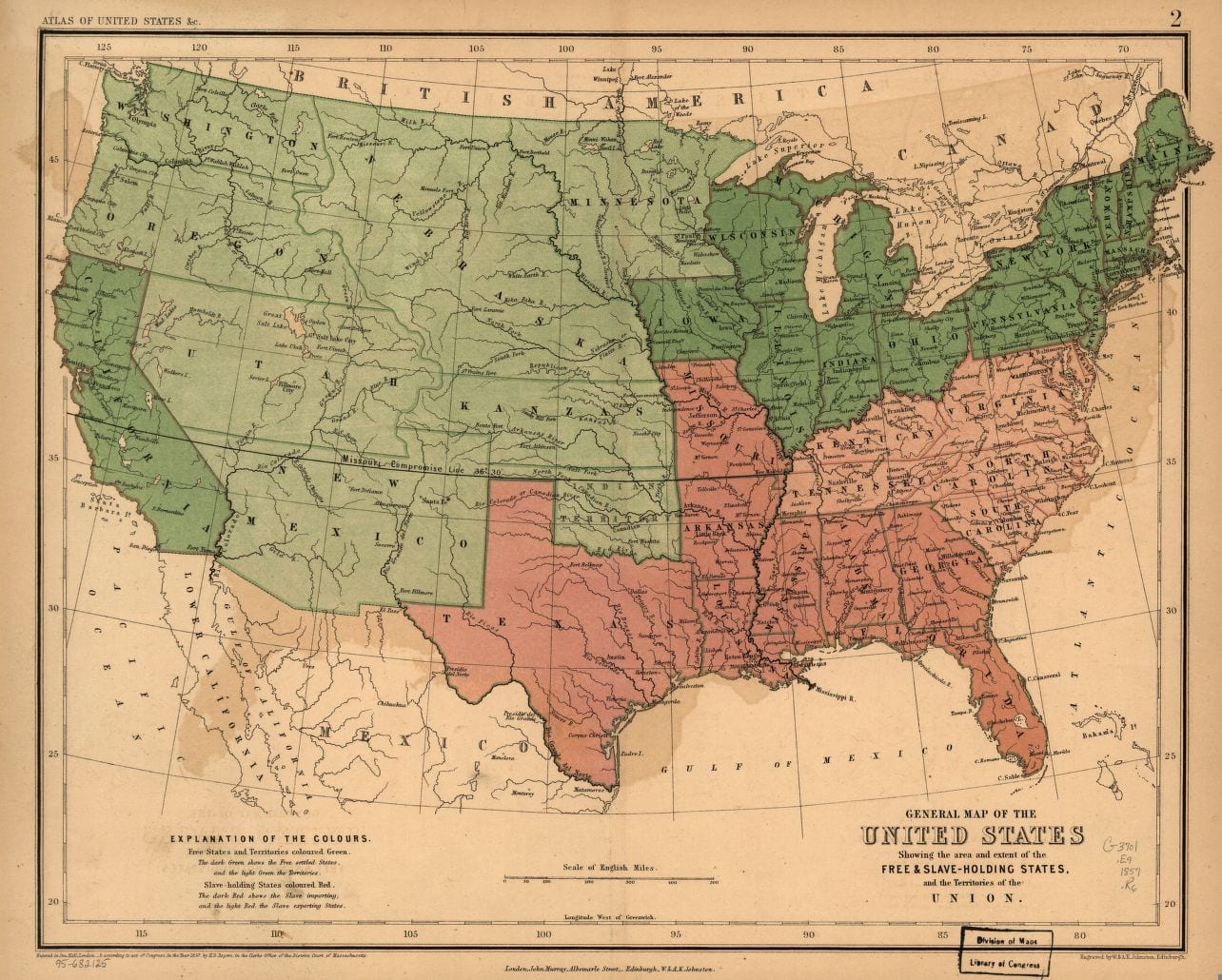

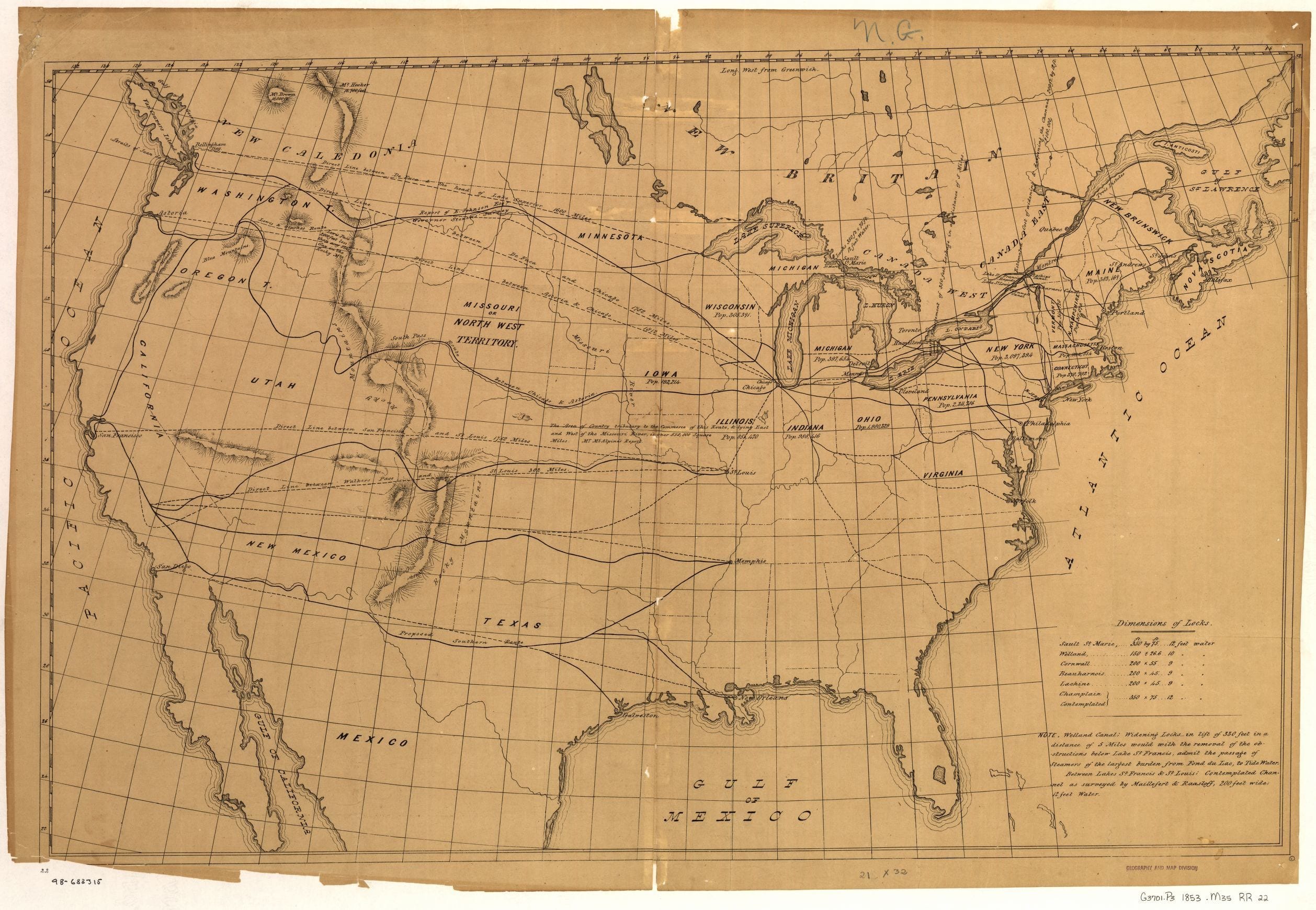

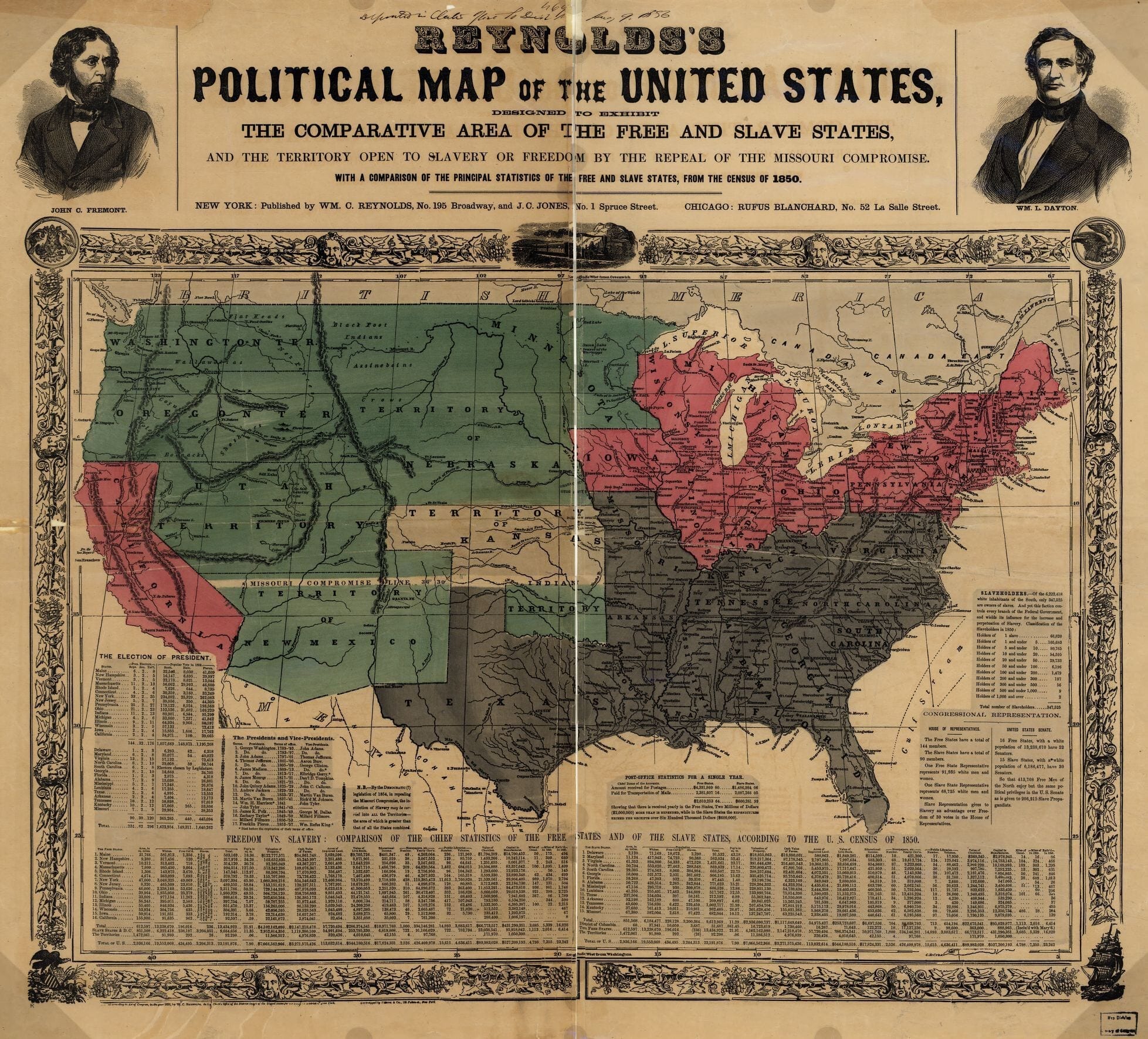

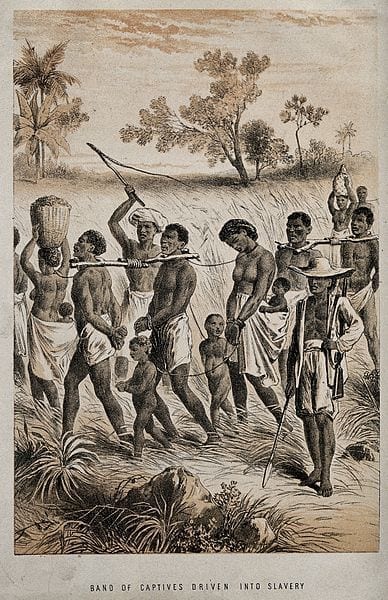

Because the government of the United States under the Constitution was designed to be neither wholly national nor wholly federal, the question of how much sovereignty was retained by each of the individual states vis-à-vis the national government remained unresolved even after ratification. Indeed, some states, like Virginia and New York, explicitly included provisions outlining the right of the people either organically, or through their state governments, to resume their political authority in the event the national government proved unable to affect the purposes for which it had been established. A less dramatic version of this understanding underlay the Virginia and Kentucky Resolves of 1798/1799. Authored by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, respectively, these documents upheld a robust vision of the states as constitutional interpreters, even (in the case of Kentucky) asserting that within its own borders, a state had the ability to nullify (or, in effect, to disregard) any federal law it believed to be unconstitutional. (Madison later disavowed nullification.)

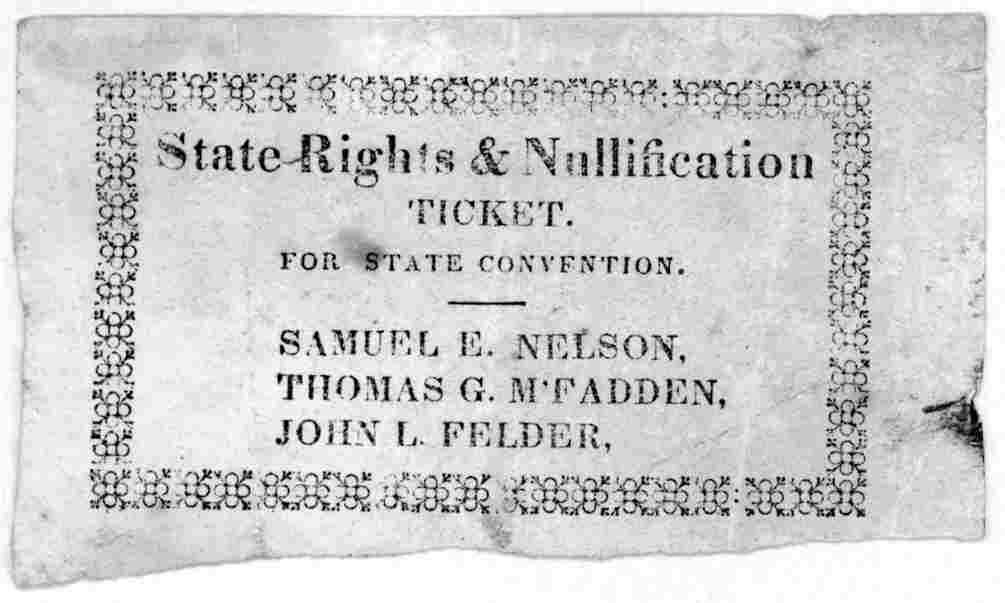

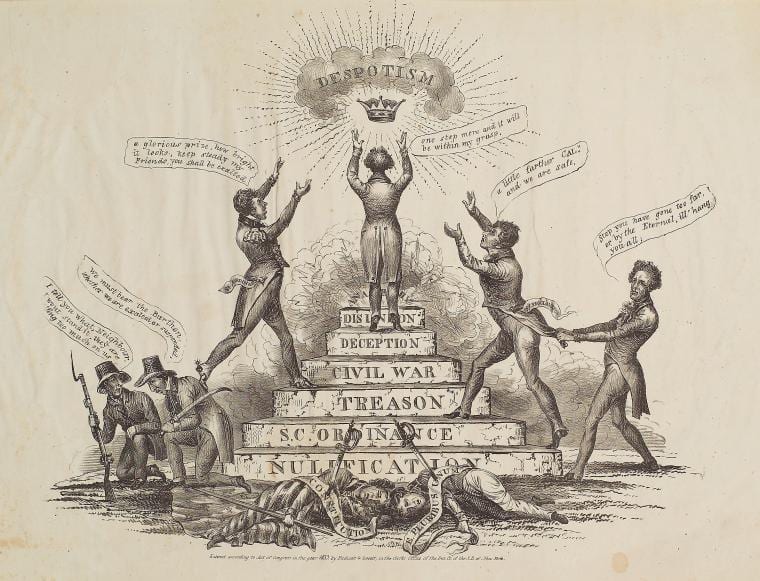

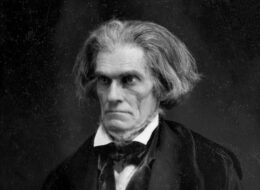

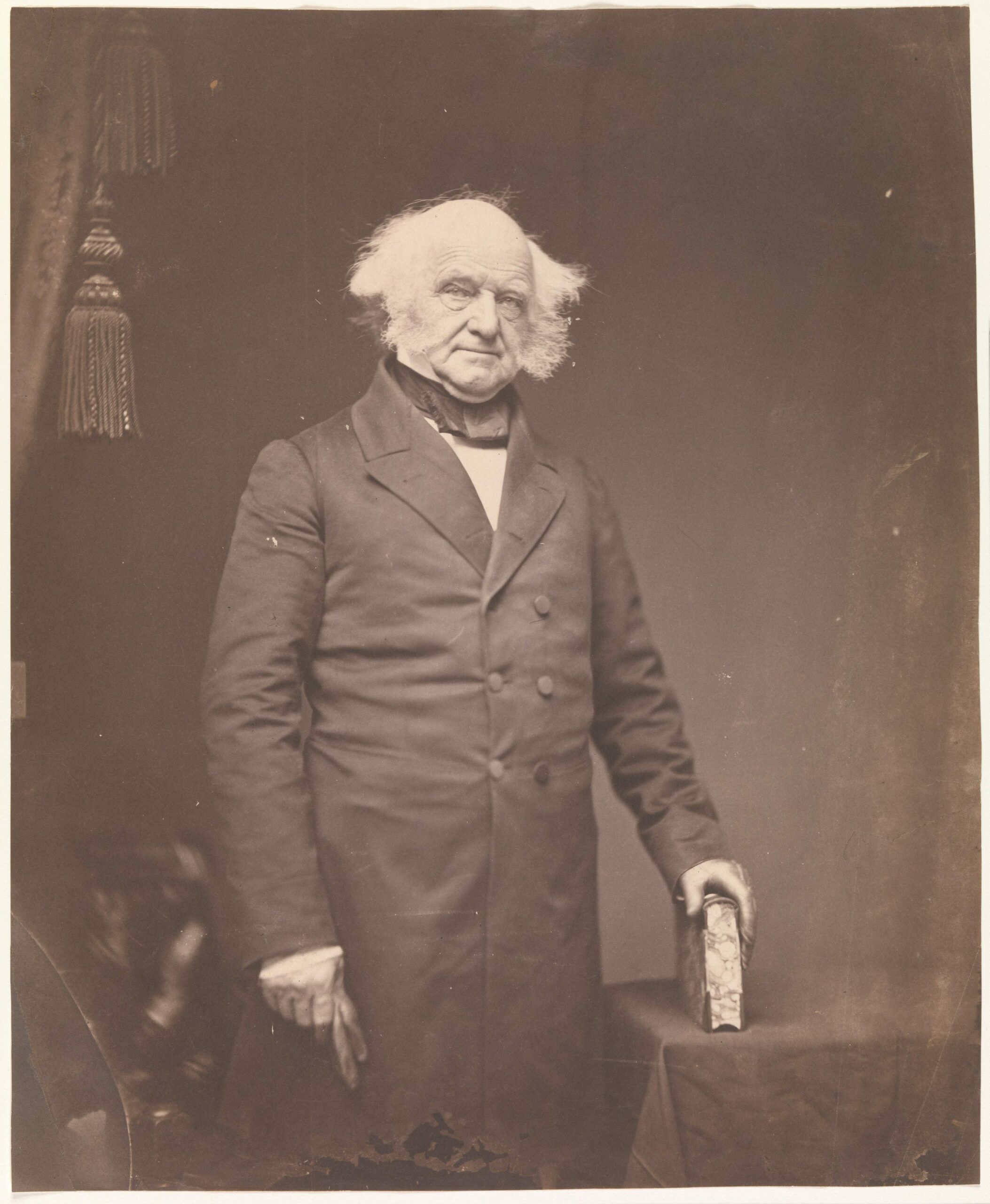

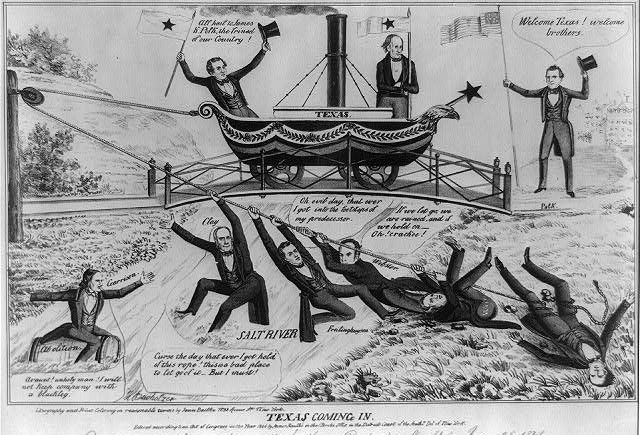

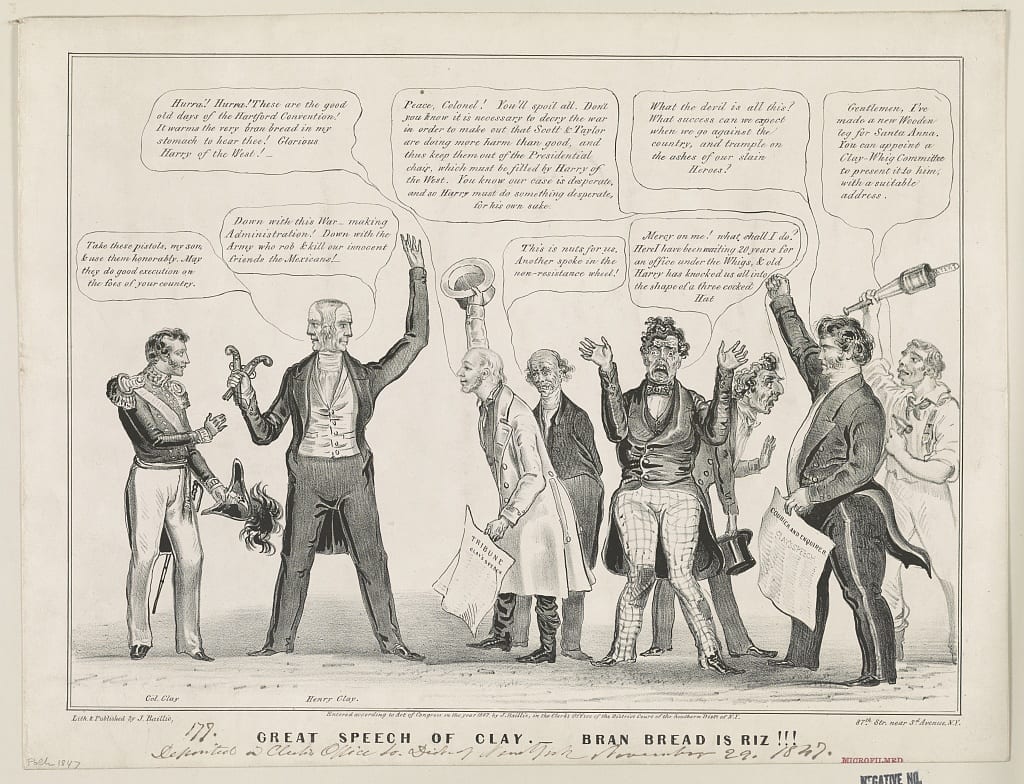

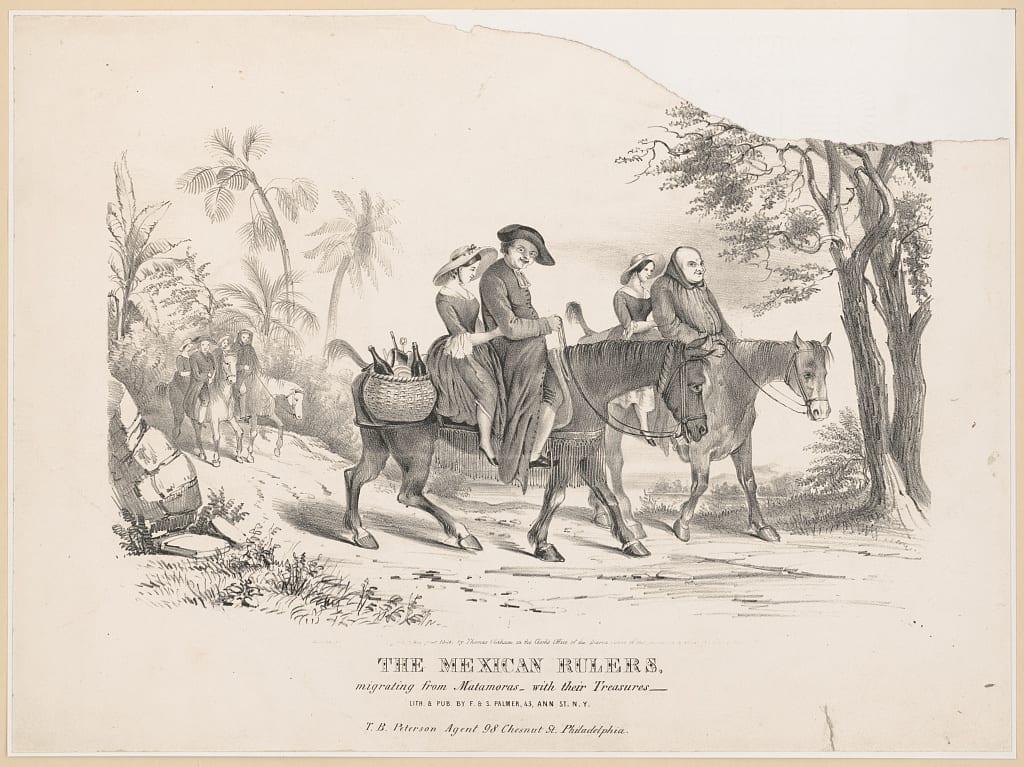

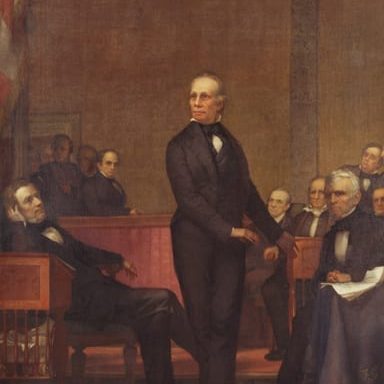

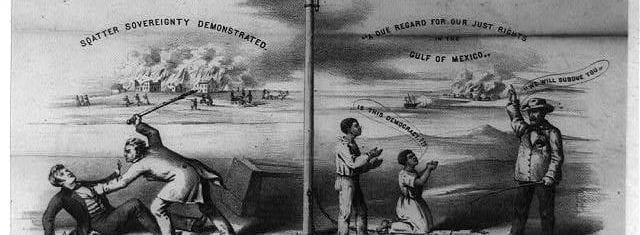

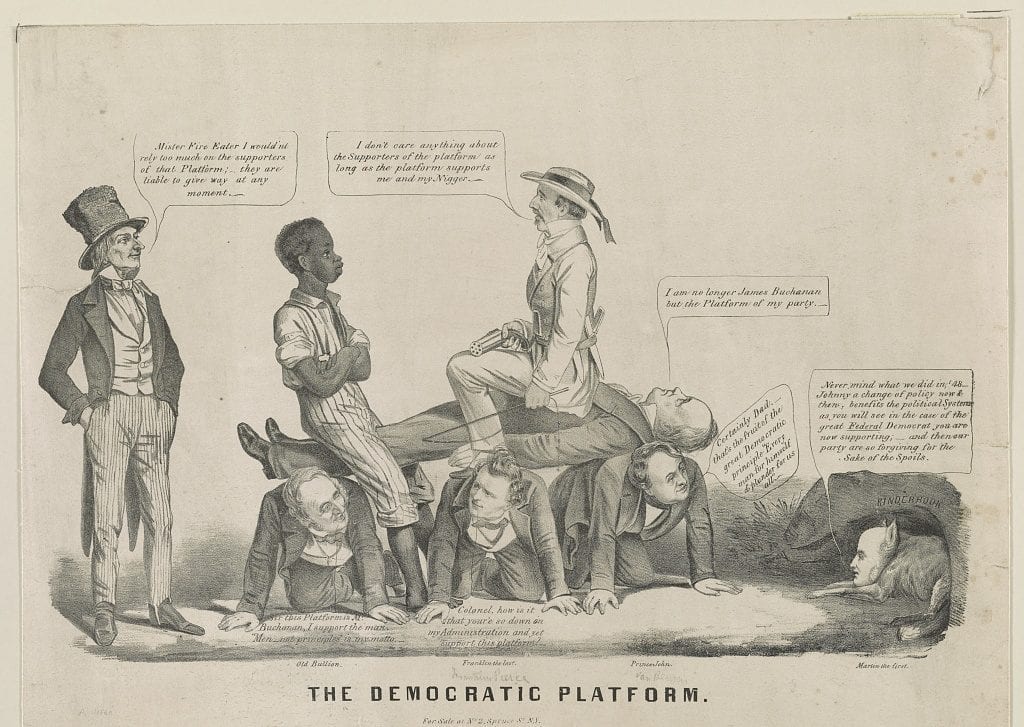

Although the 1803 Marbury v. Madison decision helped claim for the Supreme Court the power to declare laws unconstitutional, the idea that the states had a legitimate ability to weigh in on the constitutionality of federal measures (previously manifested in the Hartford Convention) gained ground in the 1820s, particularly in the agricultural South, where people viewed national economic policies as unfairly partial toward northern manufacturing. South Carolinians took the lead in protesting the federal “tariff of abominations” in 1828.

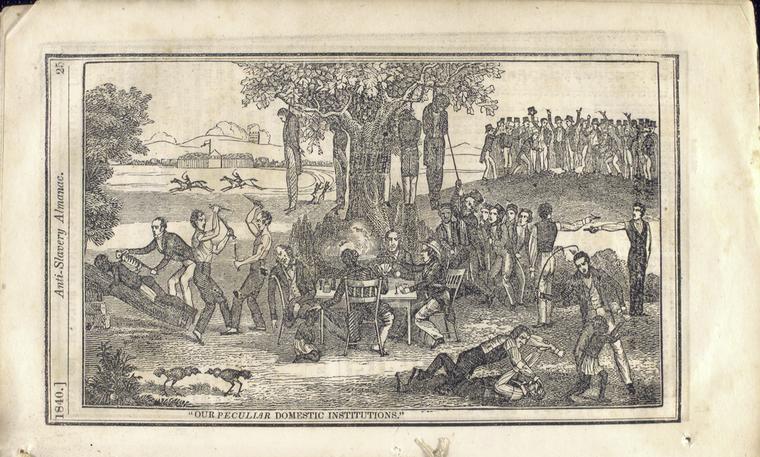

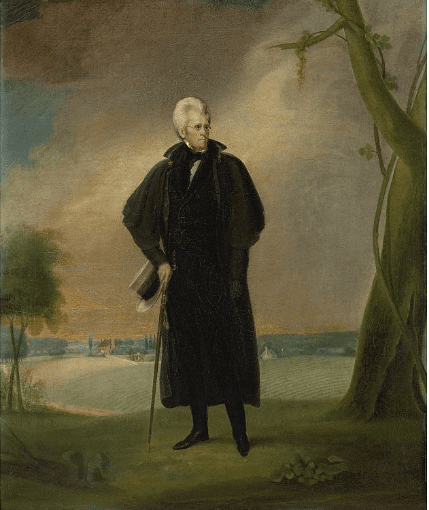

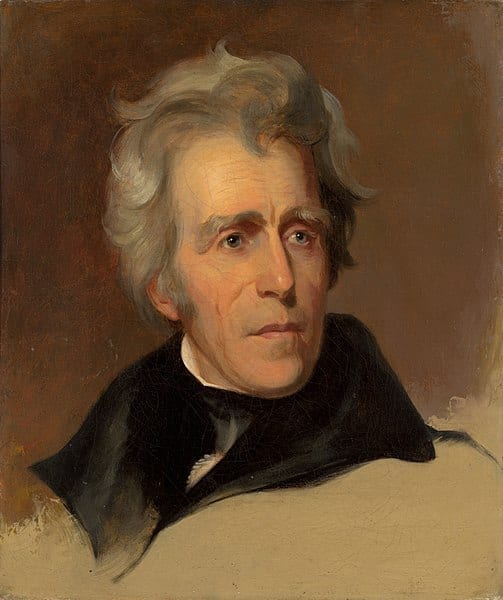

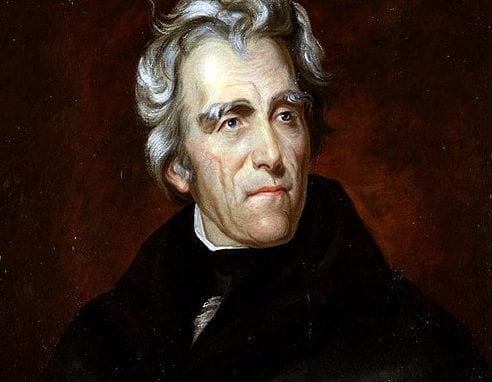

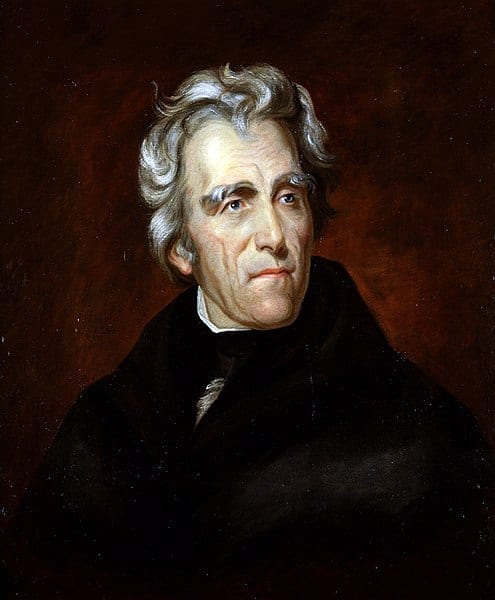

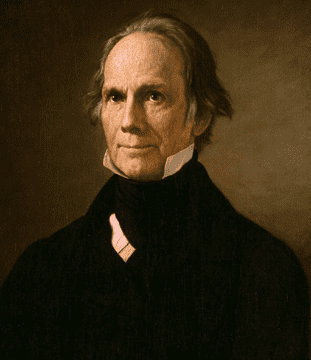

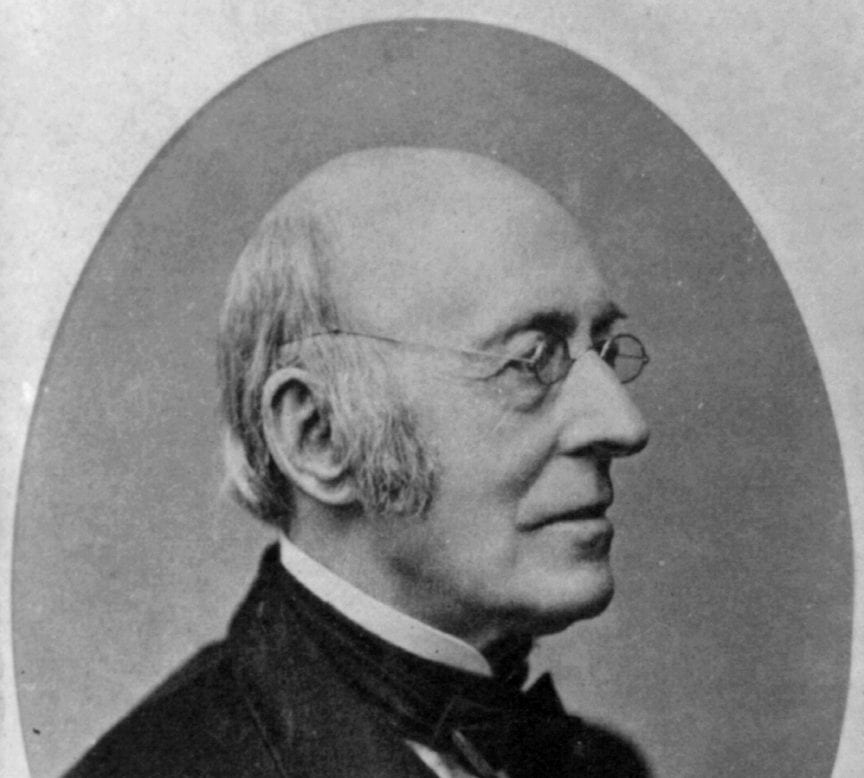

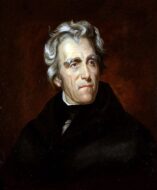

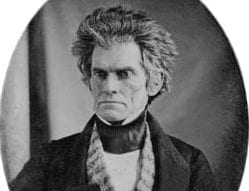

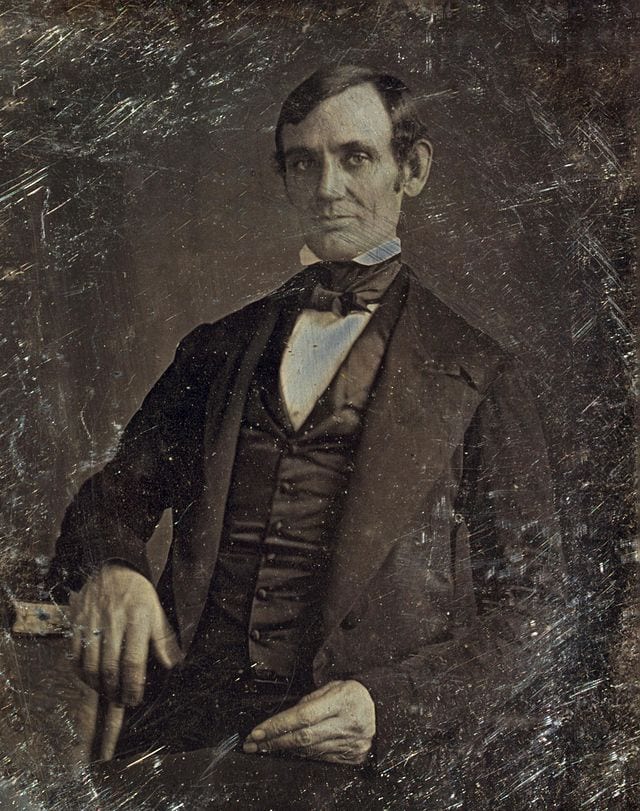

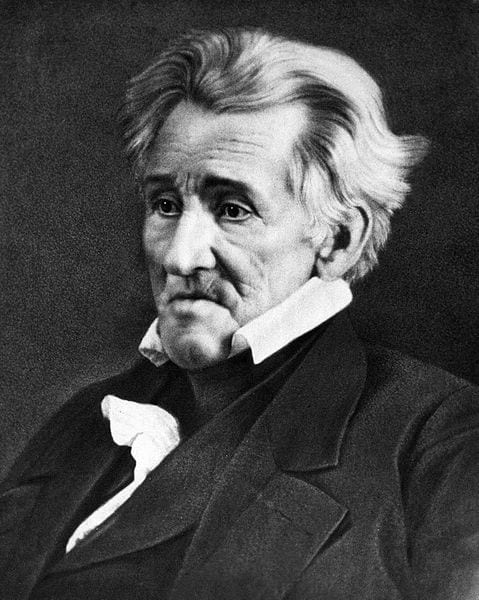

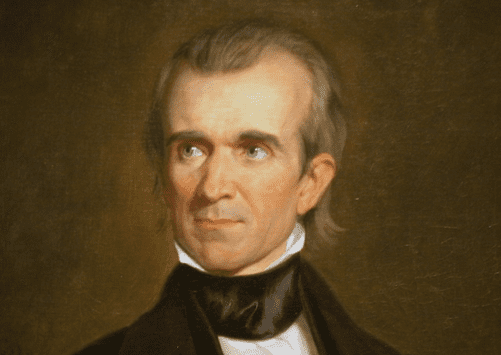

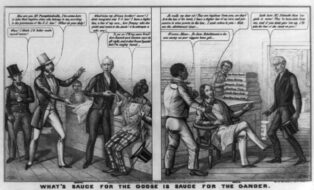

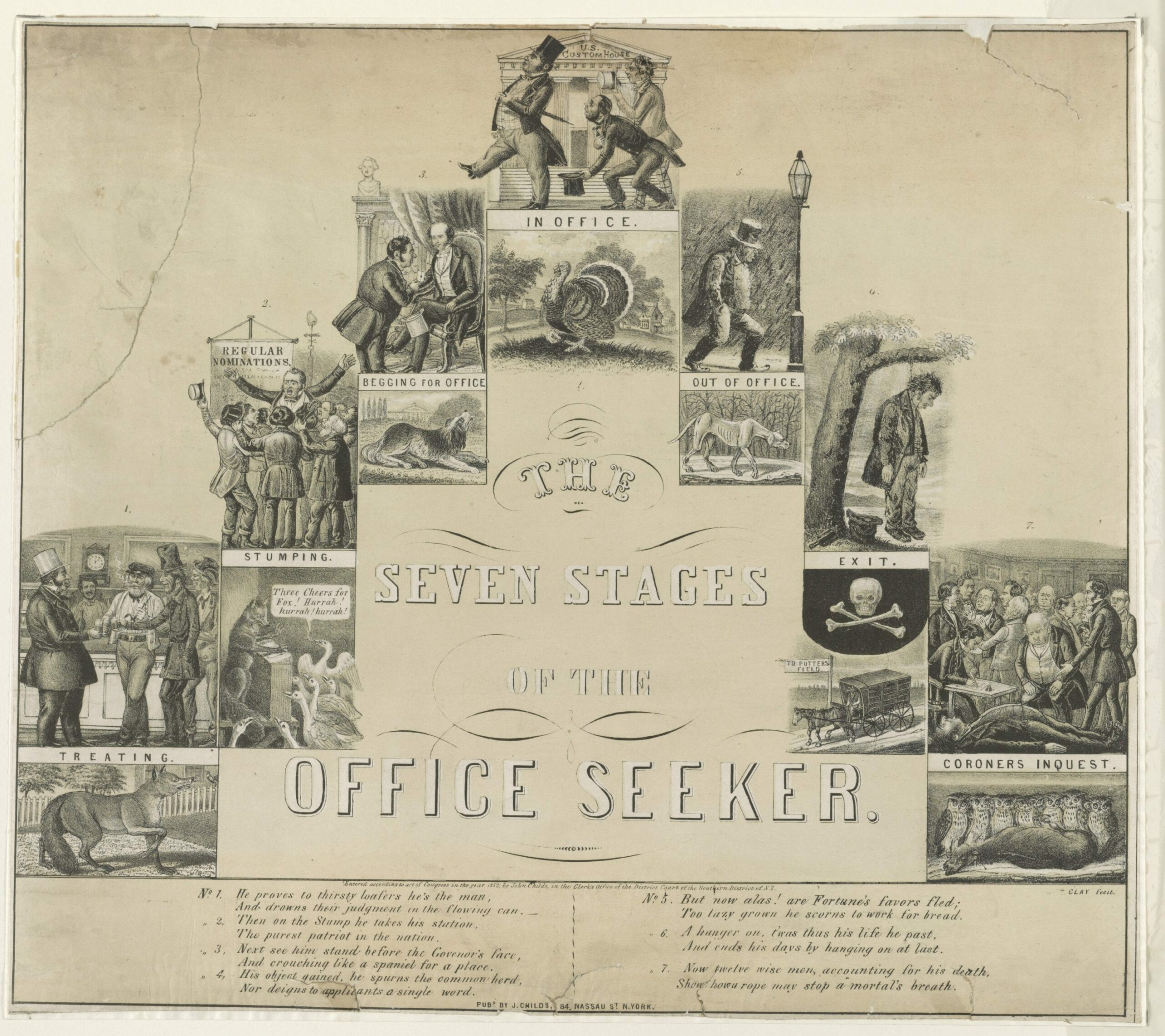

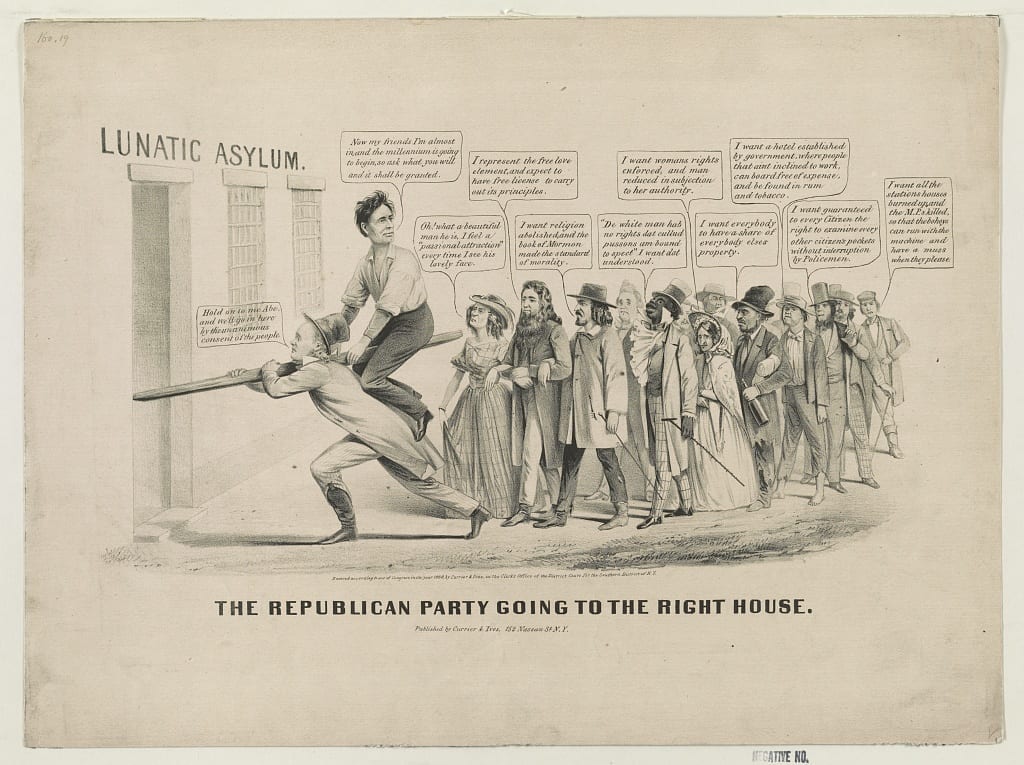

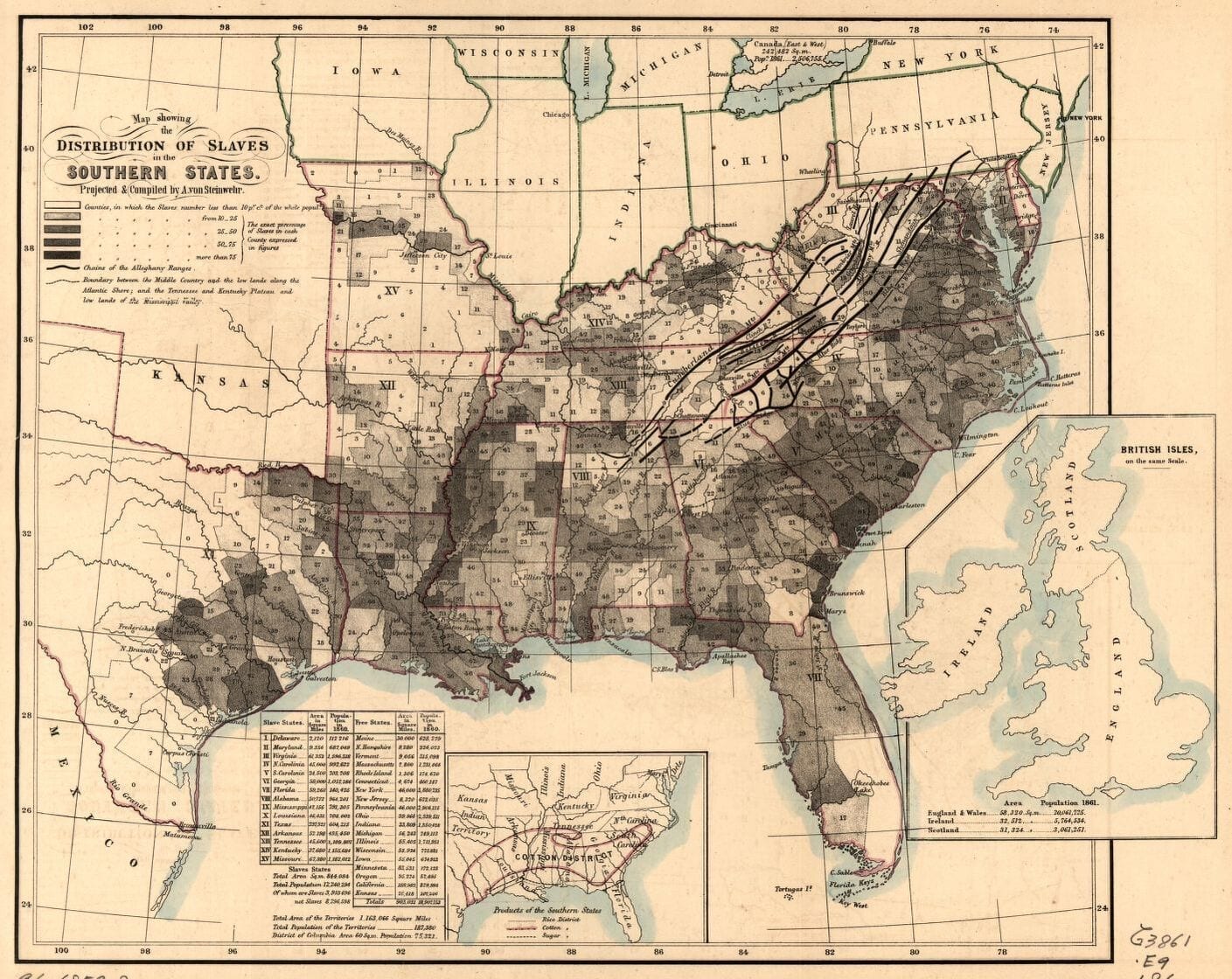

President Andrew Jackson publicly refuted all arguments in favor of nullification, and brought a swift end to South Carolina’s rhetorical rebellion by threatening to use military force against the state if it did not comply with federal law. Many Northerners believed that nullification was not only a philosophical absurdity, but also directly linked to the perpetuation of the institution of slavery. They applauded Jackson’s actions as a defense of not only the Union, but also of freedom itself. The theory of state sovereignty at the heart of nullification continued to appeal to many Americans and contributed to the deepening divide between northerners and southerners during the antebellum period, leading at least one pessimistic wag to pen an “Epitaph for the Constitution” in which he (or she) imagined the issue leading to the collapse of the Union.

Documentary History of the Constitution, Vol. II (1894), pp. 145, 190.

Virginia Ratification Statement, June 26, 1788

We, the delegates of the people of Virginia, duly elected in pursuance of a recommendation from the General Assembly, and now met in Convention, having fully and freely investigated and discussed the proceedings of the Federal Convention, and being prepared as well as the most mature deliberation hath enabled us, to decide thereon, DO in the name and on behalf of the people of Virginia, declare and make known that the powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States may be resumed by them whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression, and that every power not granted thereby remains with them and at their will. . . .

New York Ratification Statement, July 26, 1788

We, the delegates of the people of the state of New York, duly elected and met in Convention, having maturely considered the Constitution of the United States of America . . . and having also seriously and deliberately considered the present situation of the United States, – do declare and make known –

That all power is originally vested in, and consequently derived from, the people, and that government is instituted by them for their common interest, protection, and security.

That the enjoyment of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, are essential rights, which every government ought to respect and preserve.

That the powers of government may be reassumed by the people whensoever it shall become necessary to their happiness; that every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by the said Constitution clearly delegated to the Congress of the United States, or the departments of the government thereof, remains to the people of the several states, or to their respective state governments, to whom they may have granted the same; and that those clauses in the said Constitution, which declare that Congress shall not have or exercise certain powers, do not imply that Congress is entitled to any powers not given by the said Constitutions; but such clauses are to be construed either as exceptions to certain specified powers, or as inserted merely for greater caution. . . .