No related resources

Introduction

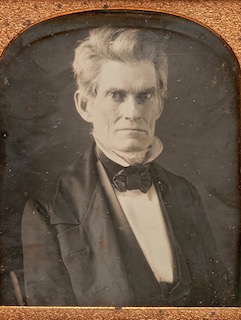

On April 12, 1844, Secretary of State John C. Calhoun (1782–1850) and two negotiators from the Republic of Texas formally signed a treaty of annexation under which Texas would become a U.S. territory eligible for admission as one or more states. The boundaries of Texas were not specified but left to be sorted out later with Mexico. Ten days later the treaty went to the Senate. Along with it went Calhoun’s official statement of why Texas’ annexation was essential: a letter from the secretary of state to Britain’s minister to the United States, Richard Pakenham, which declared that the United States acquired Texas in order to protect slavery there from British interference.

Calhoun, a South Carolinian, sought something more than Texas—he sought domestic and international recognition of the moral righteousness and permanent legitimacy of slavery. In his letter Calhoun launched into a defense of slavery as an institution for the uplift of the African race, arguing that the slaves of the South were far better off than free blacks in the North. That argument caused outrage among antislavery forces and discomfited moderates, and helped to defeat the treaty in the Senate. But the letter injected slavery and Texas into the 1844 presidential campaign, which both Whig Henry Clay (1777–1852) and the presumptive Democratic presidential candidate, Martin Van Buren (1782–1862), had hoped to avoid. Clay felt he had to waffle on his Raleigh Letter, and Van Buren was defeated for his party’s nomination by James Polk (1795–1849), an ardent expansionist, who narrowly won over Clay in the general election. The annexation of Texas would be accomplished by a joint resolution of Congress as Polk came into office.

Source: The Works of John C. Calhoun, vol. 5: Reports and Public Letters of John C. Calhoun, ed. Richard K. Crallé (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1859), 333–339; available at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000366903.

The undersigned, secretary of state of the United States, has laid before the president the note of the right honorable Mr. Pakenham, envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary of Her Britannic Majesty, addressed to this department on the 26th of February last, together with the accompanying copy of a dispatch of Her Majesty’s principal secretary of state for foreign affairs to Mr. Pakenham.[1] In reply, the undersigned is directed by the president to inform the right honorable Mr. Pakenham that while he regards with pleasure the disavowal of Lord Aberdeen of any intention on the part of Her Majesty’s government “to resort to any measures, either openly or secretly, which can tend to disturb the internal tranquility of the slaveholding states, and thereby affect the tranquility of this Union,” he at the same time regards with deep concern the avowal, for the first time made to this government, “that Great Britain desires and is constantly exerting herself to procure the general abolition of slavery throughout the world.”

So long as Great Britain confined her policy to the abolition of slavery in her own possessions and colonies, no other country had a right to complain.[2] It belonged to her exclusively to determine, according to her own views of policy, whether it should be done or not. But when she goes beyond, and avows it as her settled policy, and the object of her constant exertions, to abolish it throughout the world, she makes it the duty of all other countries, whose safety or prosperity may be endangered by her policy, to adopt such measures as they may deem necessary for their protection.

It is with still deeper concern the president regards the avowal of Lord Aberdeen of the desire of Great Britain to see slavery abolished in Texas, and, as he infers, is endeavoring, through her diplomacy, to accomplish it by making the abolition of slavery one of the conditions on which Mexico should acknowledge her independence. It has confirmed his previous impressions as to the policy of Great Britain in reference to Texas, and made it his duty to examine with much care and solicitude what would be its effects on the prosperity and safety of the United States, should she succeed in her endeavors. The investigation has resulted in the settled conviction that it would be difficult for Texas, in her actual condition, to resist what she desires, without supposing the influence and exertions of Great Britain would be extended beyond the limits assigned by Lord Aberdeen; and that, if Texas could not resist the consummation of the object of her desire, would endanger both the safety and prosperity of the Union. Under this conviction, it is felt to be the imperious duty of the federal government, the common representative and protector of the states of the Union, to adopt, in self-defense, the most effectual measures to defeat it.

This is not the proper occasion to state at large the grounds of this conviction. It is sufficient to say, that the consummation of the avowed object of her wishes in reference to Texas would be followed by hostile feelings and relations between that country and the United States, which could not fail to place her under the influence and control of Great Britain. That, from the geographical position of Texas, would expose the weakest and most vulnerable portion of our frontier to inroads, and place in the power of Great Britain the most efficient means of effecting in the neighboring states of this Union what she avows to be her desire to do in all countries where slavery exists. To hazard consequences which would be so dangerous to the prosperity and safety of this Union, without resorting to the most effective measures to prevent them, would be, on the part of the federal government, an abandonment of the most solemn obligation imposed by the guarantee which the states, in adopting the Constitution, entered into to protect each other against whatever might endanger their safety, whether from without or within. Acting in obedience to this obligation, on which our federal system of government rests, the president directs me to inform you that a treaty has been concluded between the United States and Texas, for the annexation of the latter to the former as a part of its territory, which will be submitted without delay to the Senate, for its approval. This step has been taken as the most effectual, if not the only means of guarding against the threatened danger, and securing their permanent peace and welfare.

It is well known that Texas has long desired to be annexed to this Union; that her people, at the time of the adoption of her constitution, expressed, by an almost unanimous vote, her desire to that effect; and that she has never ceased to desire it, as the most certain means of promoting her safety and prosperity. The United States have heretofore declined to meet her wishes; but the time has now arrived when they can no longer refuse, consistently with their own security and peace, and the sacred obligation imposed by their constitutional compact for mutual defense and protection. Nor are they any way responsible for the circumstances which have imposed this obligation on them. They had no agency in bringing about the state of things which has terminated in the separation of Texas from Mexico. It was the Spanish government and Mexico herself which invited and offered high inducements to our citizens to colonize Texas. That, from the diversity of character, habits, religion, and political opinions, necessarily led to the separation, without the interference of the United States in any manner whatever. It is true the United States at an early period, recognized the independence of Texas; but, in doing so, it is well known they but acted in conformity with an established principle to recognize the government de facto.[3] They had previously acted on the same principle in reference to Mexico herself, and the other governments which have risen on the former dominions of Spain on this continent.

They are equally without responsibility for that state of things, already adverted to as the immediate cause of imposing on them, in self-defense, the obligation of adopting the measure they have. They remained passive, so long as the policy on the part of Great Britain, which has led to its adoption, had no immediate bearing on their peace and safety. While they conceded to Great Britain the right of adopting whatever policy she might deem best, in reference to the African race, within her own possessions, they on their part claim the same right for themselves. The policy she has adopted in reference to the portion of that race in her dominions may be humane and wise; but it does not follow, if it prove so with her, that it would be so in reference to the United States and other countries, whose situation differs from hers. . . .

It belongs not to the government to question whether the former have decided wisely or not; and if it did, the undersigned would not regard this as the proper occasion to discuss the subject. He does not, however, deem it irrelevant to state that, if the experience of more than half a century is to decide, it would be neither humane nor wise in them to change their policy. The census and other authentic documents show that in all instances in which the states have changed the former relation between the two races, the condition of the African, instead of being improved, has become worse. They have been invariably sunk into vice and pauperism, accompanied by the bodily and mental inflictions incident thereto—deafness, blindness, insanity, and idiocy—to a degree without example; while, in all other states which have retained the ancient relation between them, they have improved greatly in every respect—in number, comfort, intelligence, and morals—as the following facts, taken from such sources, will serve to illustrate. . . .

If such be the wretched condition of the race in their changed relation, where their number is comparatively few, and where so much interest is manifested for their improvement, what would it be in those states where the two races are nearly equal in numbers, and where, in consequence, would necessarily spring up mutual fear, jealousy, and hatred between them? It may, in truth, be assumed as a maxim, that two races differing so greatly, and in so many respects, cannot possibly exist together in the same country, where their numbers are nearly equal, without the one being subjected to the other. Experience has proved that the existing relation, in which the one is subjected to the other, in the slaveholding states, is consistent with the peace and safety of both, with great improvement to the inferior; while the same experience proves that the relation which it is the desire and object of Great Britain to substitute in its stead, in this and all other countries, under the plausible name of the abolition of slavery, would (if it did not destroy the inferior by conflicts, to which it would lead) reduce it to the extremes of vice and wretchedness. In this view of the subject, it may be asserted, that what is called slavery is in reality a political institution, essential to the peace, safety, and prosperity of those states of the Union in which it exists. Without, then, controverting the wisdom and humanity of the policy of Great Britain, so far as her own possessions are concerned, it may be safely affirmed, without reference to the means by which it would be effected, that, could she succeed in accomplishing, in the United States, what she avows to be her desire and the object of her constant exertions to effect throughout the world, so far from being wise or humane, she would involve in the greatest calamity the whole country, and especially the race which it is the avowed object of her exertions to benefit. . . .

- 1. How would Calhoun respond to the arguments of Clay in the Raleigh letter? Would the prospects for sectional harmony, and further expansion, have been increased by the division of Texas into a free and a slave state?

- 2. The Slave Emancipation Act (1831) gave slaves in most of the British Empire their freedom, albeit after a set period of years. Plantation owners received compensation for the loss of their slaves in the form of a government grant set at a total of £20 million, equivalent to approximately $3 billion today.

- 3. The government actually in power.

Annual Message to Congress (1844)

December 03, 1844

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.