No related resources

Introduction

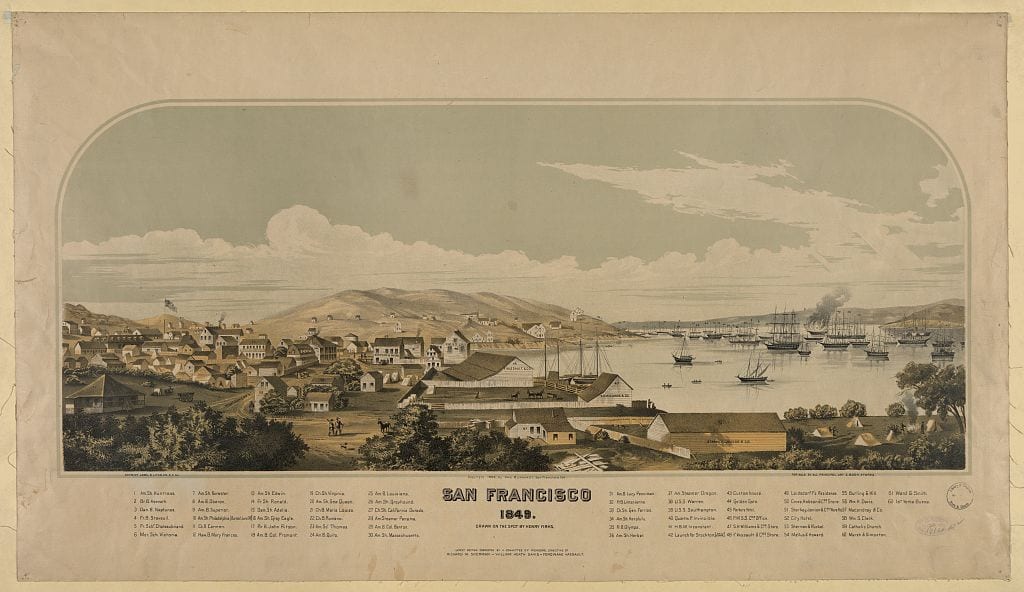

Following the discovery of gold in California in 1848, the population of San Francisco grew rapidly, perhaps twenty-fold or more over the next few years. The state of California had been admitted to the Union in 1850, and both state and local governments were immature. In the opinion of some, the institutions of civil and political life were in such poor shape that they allowed lawlessness and both financial and political corruption to flourish in the city. On two occasions these people felt compelled to take matters into their own hands. In 1851 and again in 1856, vigilance committees were formed, each operating for several months. The committees arrested, tried, and punished those they felt had broken the law or offended against public order. They sentenced eight people to death and banished others.

Both committees consisted largely of established leading citizens. Their concern over disorder and violence had a basis in fact. For example, historians estimate the murder rate in San Francisco between 1849 and 1856 to have been six times the murder rate the city suffered in 1997. (During the 1850s, Los Angeles County is thought to have had the highest murder rate in American history.) The 1856 Vigilance Committee, which claimed to have six thousand adherents, put perhaps two thousand or so uniformed and armed members in the streets organized in military fashion. It also had a more explicitly political purpose than the 1851 committee in its aims to remove foreign criminals from the city, and from political power the largely Irish immigrants who dominated city politics. (Some of the foreign criminals had been transported by the British to Australia and then found their way to San Francisco.) The state government, and especially the state judiciary, opposed the vigilantes, but the local militia tended to side with them. After the committee disbanded in August 1856, it turned itself into the People’s Party and through popular support controlled San Francisco’s politics for a number of years, eventually merging with the Republican Party. The Irish immigrants, many from New York City, identified with the Democratic Party.

As their Proclamation makes clear, the 1856 Vigilance Committee appealed to the most fundamental of American political principles to justify its actions—the right of the people to govern themselves—as laid out in the most fundamental of American documents, the Declaration of Independence. Its members therefore appealed, as the Declaration does, to the right of the people to form a new government to secure their safety and happiness when their current government fails to do so. In this appeal to popular sovereignty, the vigilante movement was part of the nineteenth-century debate over whether the power of the people had any limit, and in what ways it could be exercised legitimately. The critical issue in this regard was slavery, of course. (For an examination of the issue of popular rule and anarchy, see Abraham Lincoln, “Lyceum Address”)

The vigilance movement was also part of a long-standing American tradition of direct citizen action in the name of what participants or organizers believed was justice or community order. The tradition began at least with the Regulator movement in North Carolina (1765–1771) and includes the militia as a military organization, as well as the famous posses that helped western sheriffs apprehend horse thieves and other criminals. The tradition also includes lynching and contemporary, sometimes violent, confrontations over the use of federally controlled land in the West.

Source: “Proclamation of the Vigilance Committee of San Francisco, June 9, 1856,” in San Francisco Vigilance Committee of ’56, with some interesting sketches of events succeeding 1846, ed. Frank Merriweather Smith (San Francisco: Barry, Baird and Co., 1883), 59–61, available at https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=JZaqccBZqWEC&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA59.

TO THE PEOPLE OF CALIFORNIA

The Committee of Vigilance, placed in the position they now occupy by the voice and countenance of the vast majority of their fellow citizens, as executors of their will, desire to define the necessity which has forced this people into their present organization.

Great public emergencies demand prompt and vigorous remedies. The people—long suffering under an organized despotism which has invaded their liberties—squandered their property—usurped their offices of trust and emolument—endangered their lives—prevented the expression of their will through the ballot box, and corrupted the channels of justice—have now arisen in virtue of their inherent right and power. All political, religious, and sectional differences and issues have given way to the paramount necessity of a thorough and fundamental reform and purification of the social and political body. The voice of a whole people has demanded union and organization as the only means of making our laws effective and regaining the rights of free speech, free vote, and public safety.

For years they have patiently waited and striven, in a peaceable manner, and in accordance with the forms of law, to reform the abuses which have made our city a byword. Fraud and violence have foiled every effort, and the laws to which the people looked for protection, while destroyed and rendered effete in practice, so as to shield the vile, have been used as a powerful engine to fasten upon us tyranny and misrule.

As Republicans,[1] we looked to the ballot box as our safeguard and sure remedy. But so effectually and so long was its voice smothered, the votes deposited in it by freemen so entirely outnumbered by ballots thrust in through fraud at midnight, or nullified by the false counts of judges and inspectors of elections at noonday, that many doubted whether the majority of the people were not utterly corrupt.

Organized gangs of bad men, of all political parties, or who assumed any particular creed from mercenary and corrupt motives, have parceled out our offices among themselves, or sold them to the highest bidders. . . .

. . . Felons from other lands and states, and unconvicted criminals equally as bad, have thus controlled public funds and property, and have often amassed sudden fortunes without having done an honest day’s work with head or hands. Thus the fair inheritance of our city has been embezzled and squandered—our streets and wharves are in ruins, and the miserable entailment of an enormous debt will bequeath sorrow and poverty to another generation.

Embodied in the principles of republican governments are the truths that the majority should rule, and when corrupt officials, who have fraudulently seized the reins of authority, designedly thwart the execution of the laws and avert punishment from the notoriously guilty, the power they usurp reverts back to the people from whom it was wrested.

Realizing these truths, and confident that they were carrying out the will of the vast majority of the citizens of this county, the Committee of Vigilance, under a solemn sense of the responsibility that rested upon them, have calmly and dispassionately weighed the evidences before them, and decreed the death of some and banishment of others, who by their crimes and villainies, has stained our fair land. With those that were banished this comparatively moderate punishment was chosen, not because ignominious death was not deserved, but that the effort, if any, might surely be upon the side of mercy to the criminal. There are others scarcely less guilty, against whom the same punishment has been decreed, but they have been allowed further time to arrange for their final departure, and with the hope that permission to depart voluntarily might induce repentance, and repentance amendment, they have been suffered to choose within limits their own time and method of going. . . .

Our single, heartfelt aim is the public good; the purging, from our community, of those abandoned characters whose actions have been evil continually, and have finally forced upon us the efforts we are now making. We have no favoritism as a body, nor shall there be evinced, in any of our acts, either partially, for or prejudice against any race, sect or party.

While thus far we have not discovered on the part of our constituents any indications of lack of confidence, and have no reason to doubt that the great majority of inhabitants of the county endorse our acts, and desire us to continue the work of weeding out the irreclaimable characters from the community, we have, with deep regret, seen that some of the state authorities have felt it their duty to organize a force to resist us. It is not impossible for us to realize, that not only those who have sought place[2] with a view to public plunder, but also those gentlemen who, in accepting offices to which they were honestly elected, have sworn to support the laws of the state of California, find it difficult to reconcile their supposed duties with acquiescence in the acts of the Committee of Vigilance, since they do not reflect that perhaps more than three-fourths of the people of the entire state sympathize with and endorse our efforts, and as that all law emanates from the people, so that, when the laws thus enacted are not executed, the power returns to the people, and is theirs whenever they may choose to exercise it. These gentlemen would not have hesitated to acknowledge the self-evident truth, had the people chosen to make their present movement a complete revolution, recalled all the power they had delegated, and reissued it to new agents, under new forms.

Now, because the people have not seen fit to resume all the powers they have confided to executive or legislative officers, it certainly does not follow that they cannot, in the exercise of their inherent sovereign power, withdraw from corrupt and unfaithful servants, the authority they have used to thwart the ends of justice. . . .

The Committee of Vigilance believe that the people have entrusted to them the duty of gathering evidence, and, after due trial, expelling from the community those ruffians and assassins who have so long outraged the peace and good order of society, violated the ballot box, overridden law, and thwarted justice. Beyond the duties incident to this, we do not desire to interfere with the details of government.

We have spared and shall spare no effort to avoid bloodshed or civil war; but undeterred by threats or opposing organizations, shall continue, peaceably if we can, forcibly if we must, this work of reform, to which we have pledged our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.

Our labors have been arduous, our deliberations have been cautious, our determinations firm, our counsels prudent, our motives pure; and while regretting the imperious necessity which called us into action, we are anxious that this necessity should exist no longer; and when our labors shall have been accomplished, when the community shall be freed from the evils it has so long endured; when we have insured to our citizens an honest and vigorous protection of their rights, then the Committee of Vigilance will find great pleasure in resigning their power into the hands of the people, from whom it was received.

Published by order of the Committee.

No. 33 SECRETARY

- 1. In calling themselves Republicans, members of the committee probably meant that they were among those who believed in self-government, but given that their opponents were often Irish Catholics who identified with the Democratic Party, the committee might have been identifying themselves as members of the newly emergent Republican Party.

- 2. Public office or position

Annual Message to Congress (1856)

December 02, 1856

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.