No study questions

No related resources

Introduction

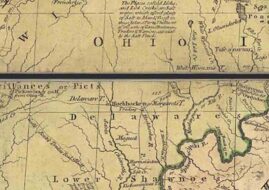

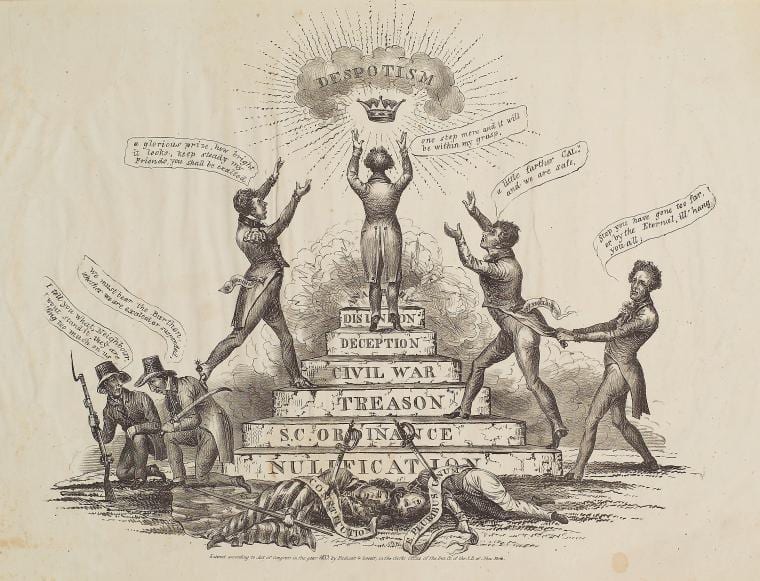

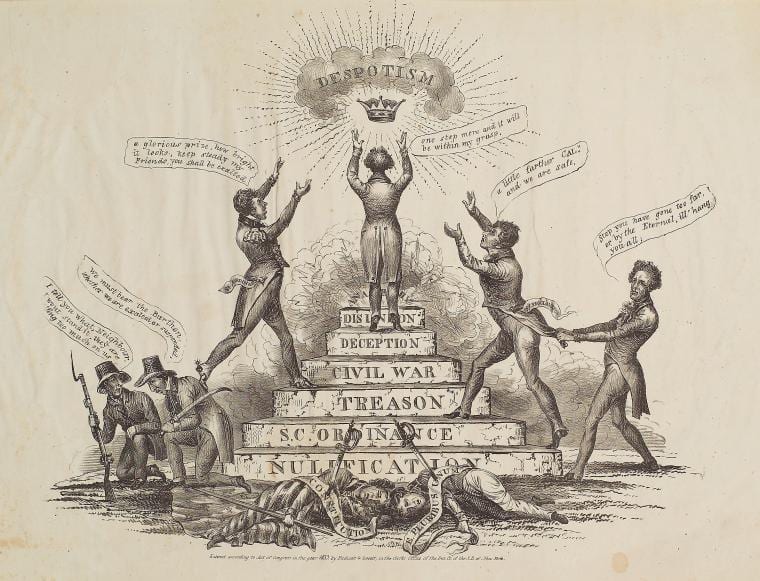

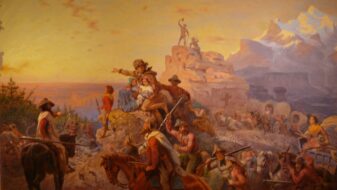

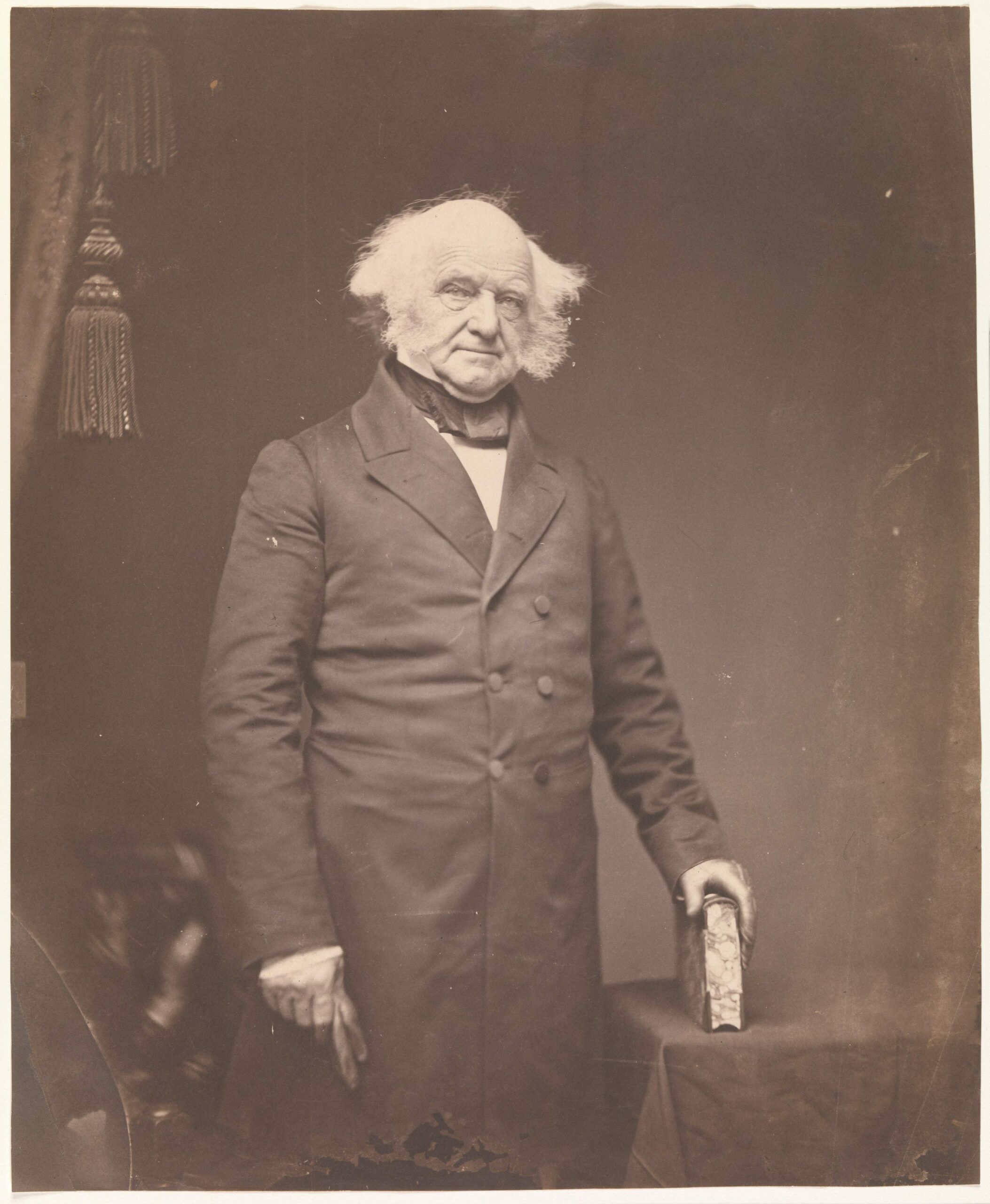

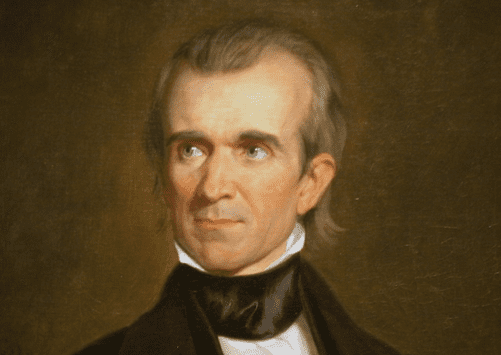

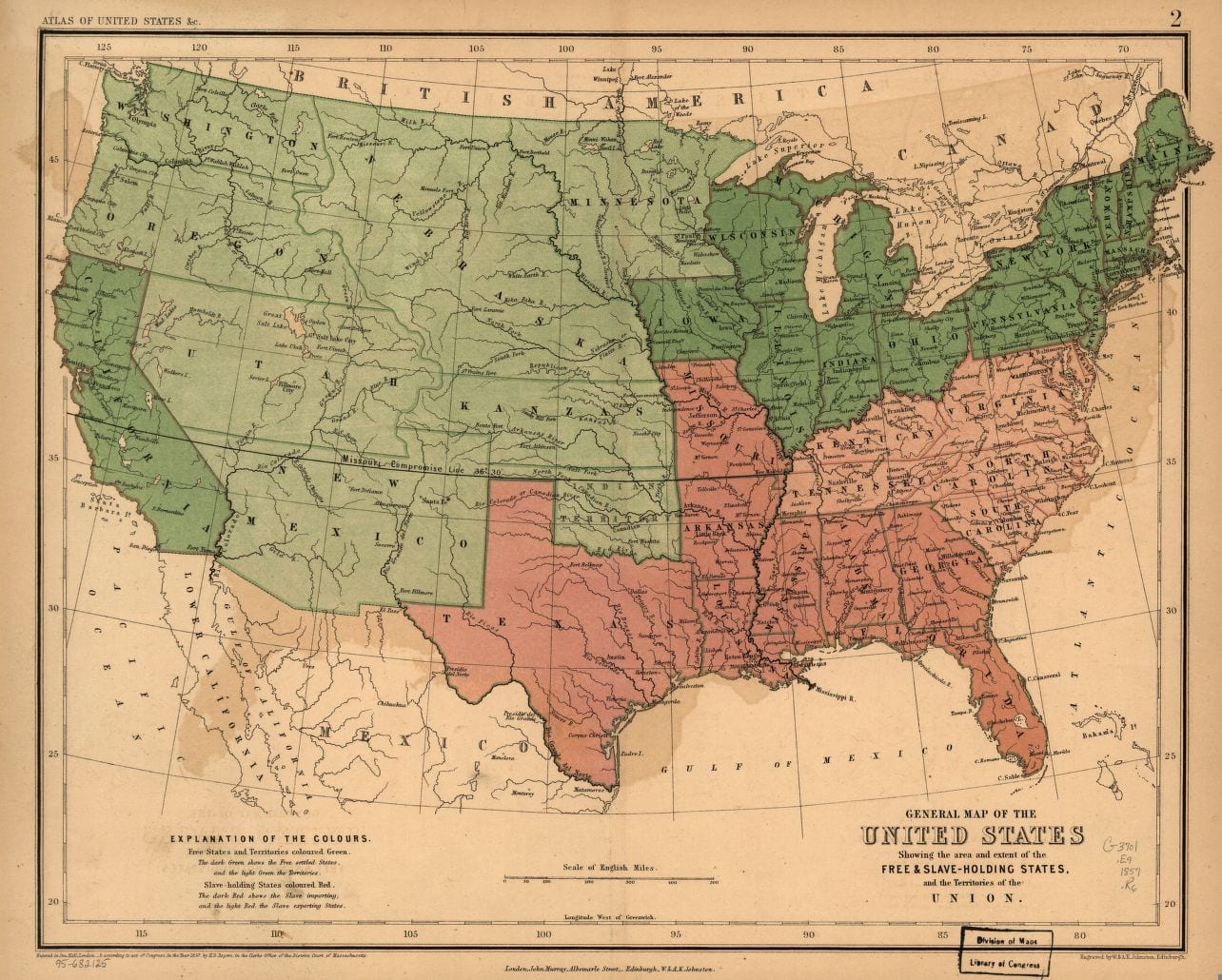

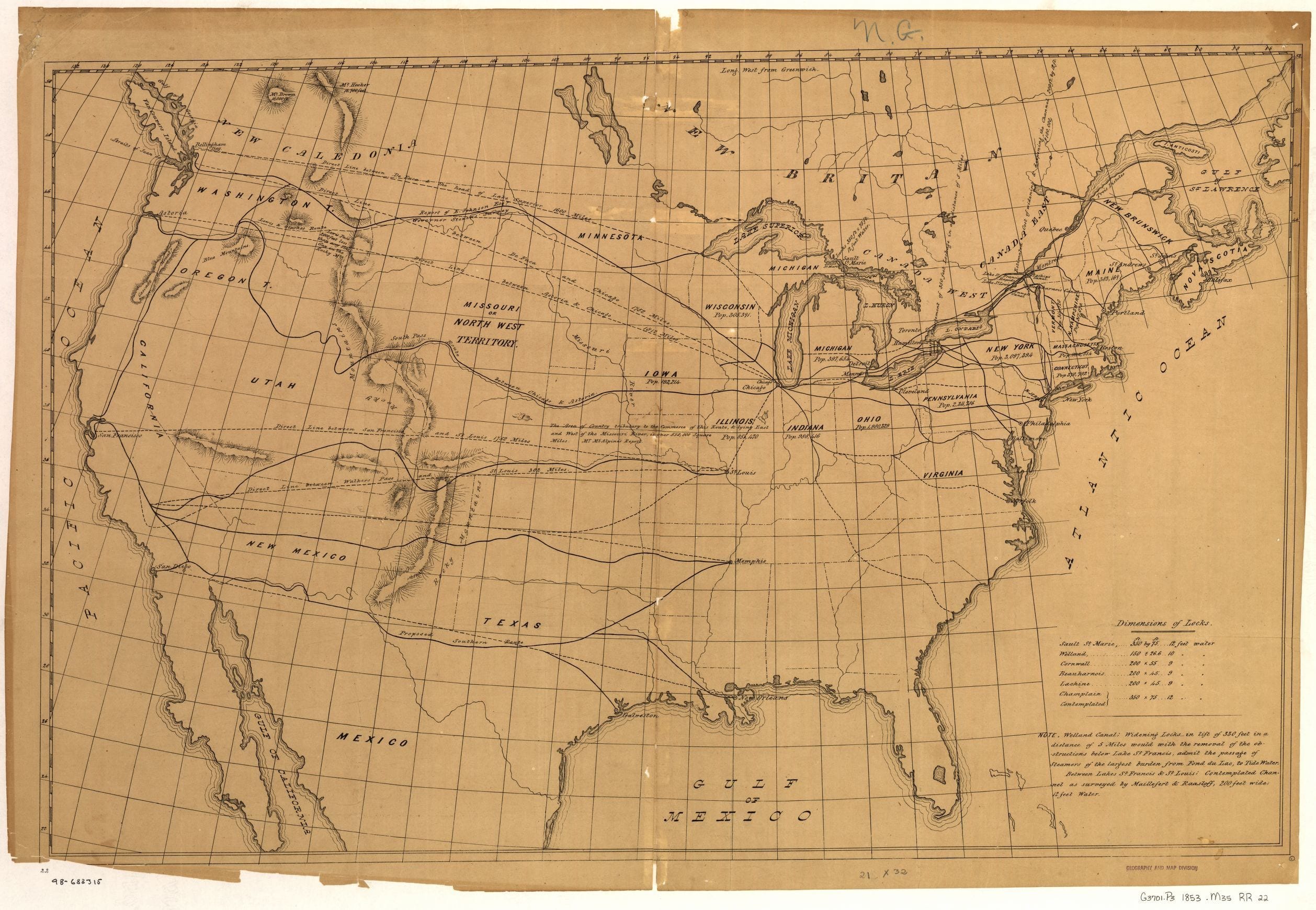

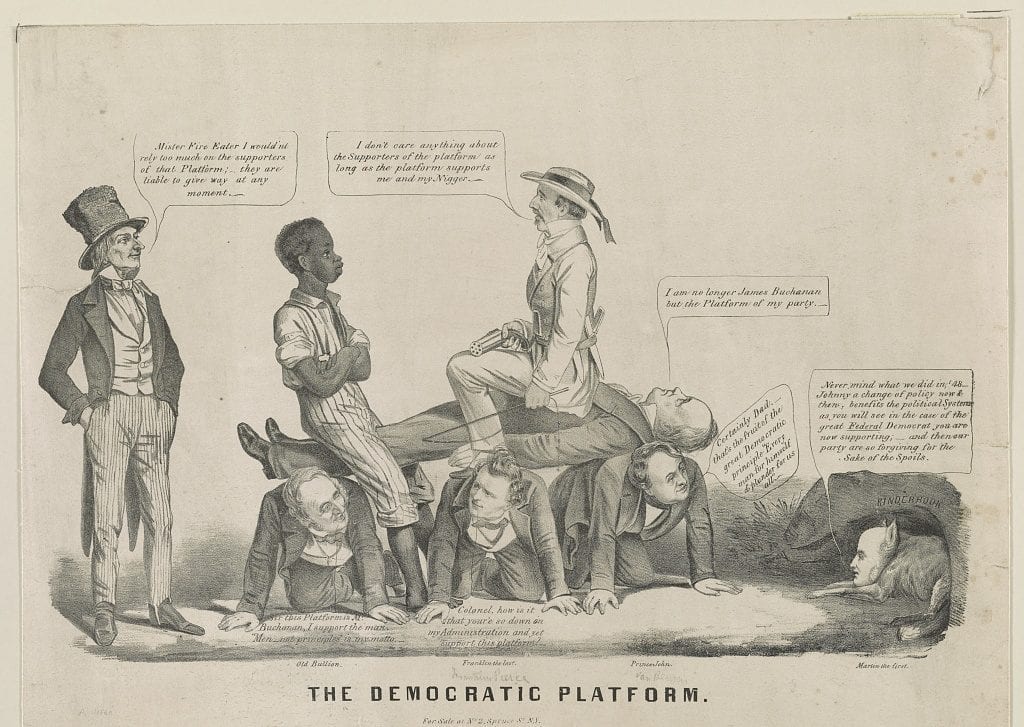

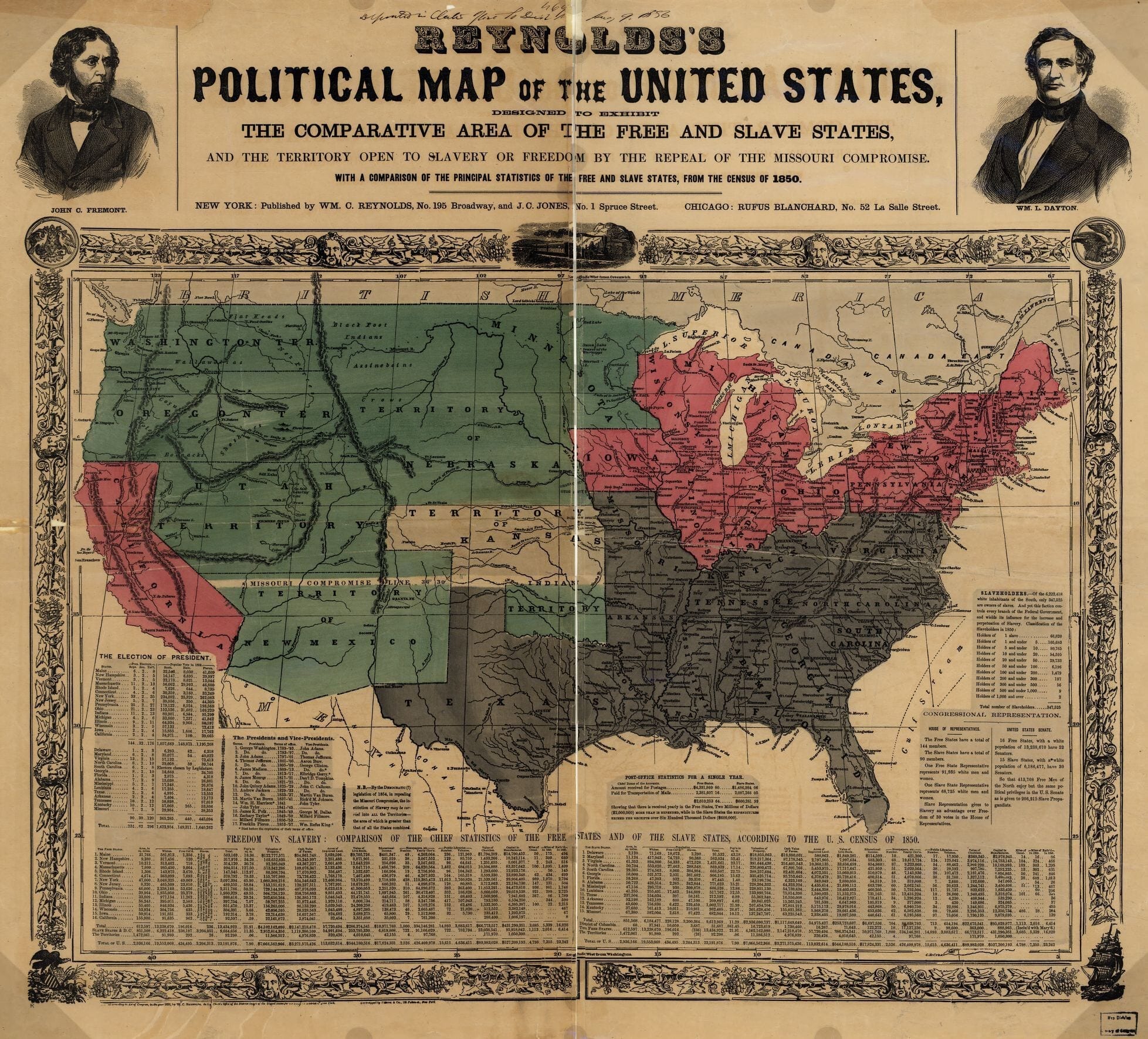

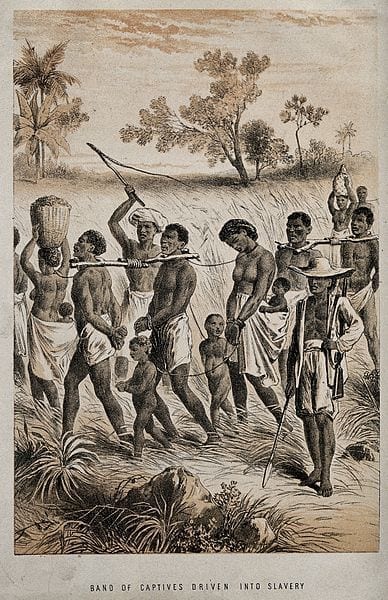

Because the government of the United States under the Constitution was designed to be neither wholly national nor wholly federal, the question of how much sovereignty was retained by each of the individual states vis-à-vis the national government remained unresolved even after ratification. Indeed, some states, like Virginia and New York, explicitly included provisions outlining the right of the people either organically, or through their state governments, to resume their political authority in the event the national government proved unable to affect the purposes for which it had been established. A less dramatic version of this understanding underlay the Virginia and Kentucky Resolves of 1798/1799. Authored by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, respectively, these documents upheld a robust vision of the states as constitutional interpreters, even (in the case of Kentucky) asserting that within its own borders, a state had the ability to nullify (or, in effect, to disregard) any federal law it believed to be unconstitutional. (Madison later disavowed nullification.)

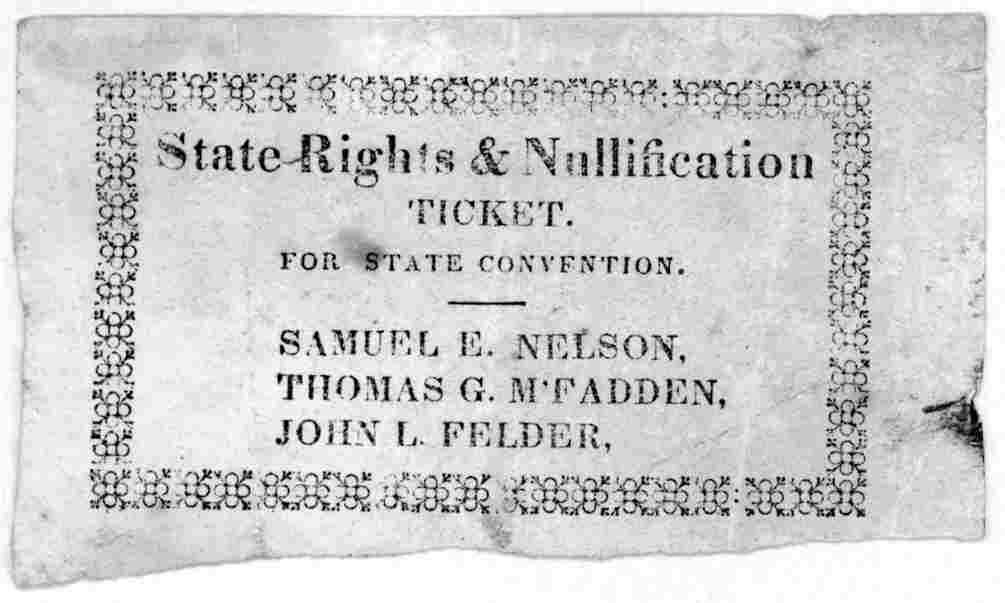

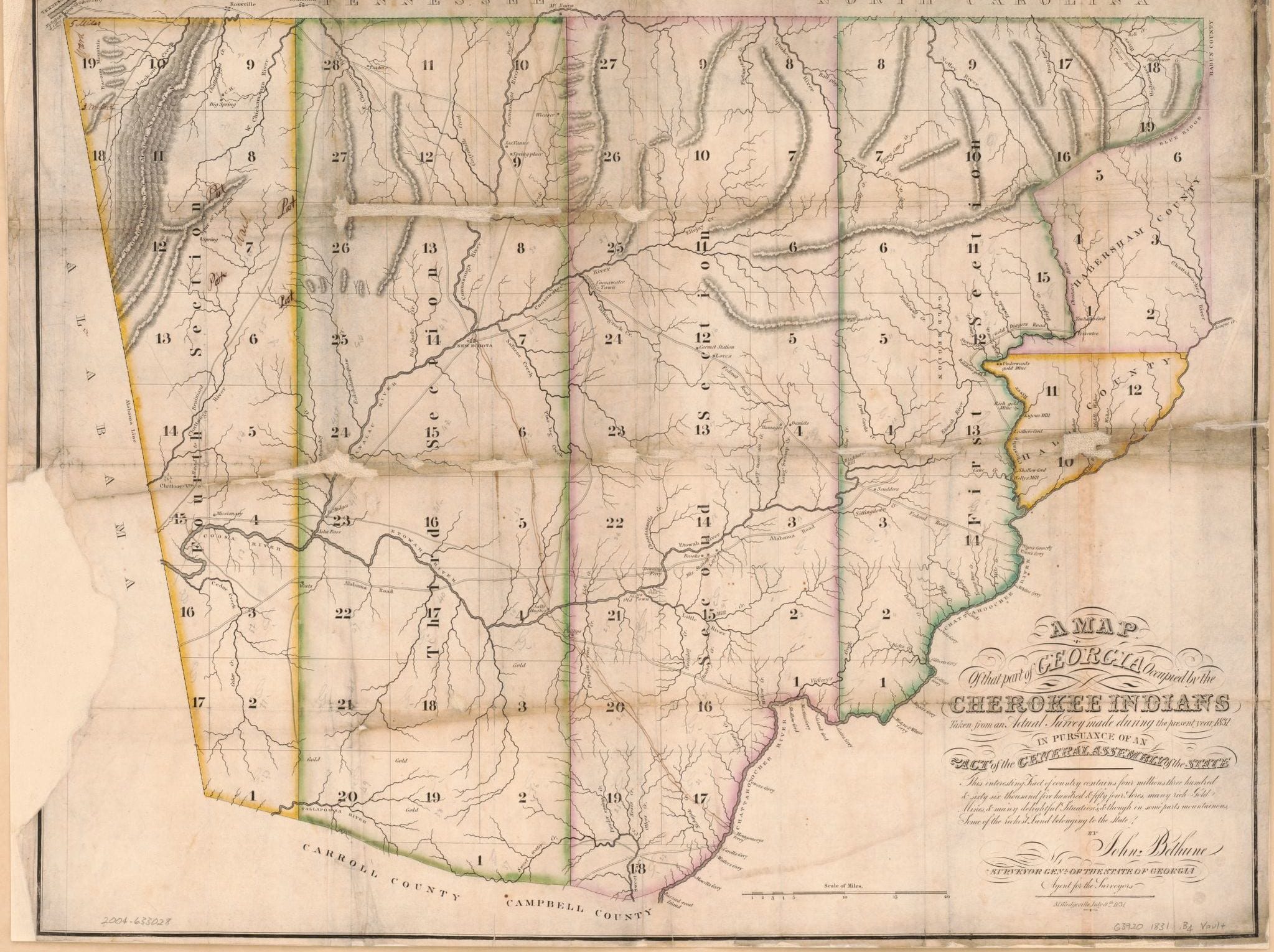

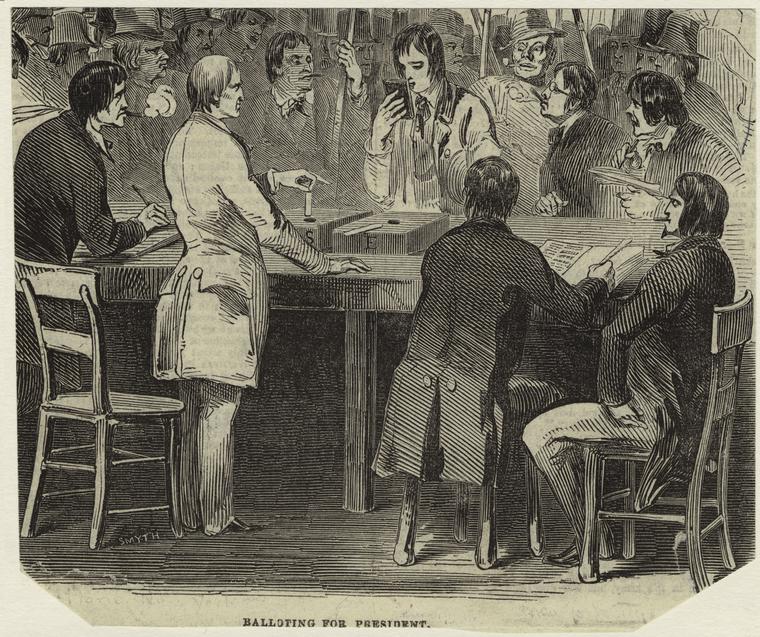

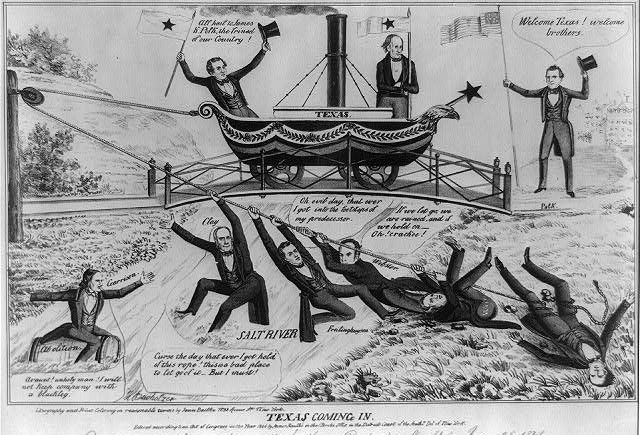

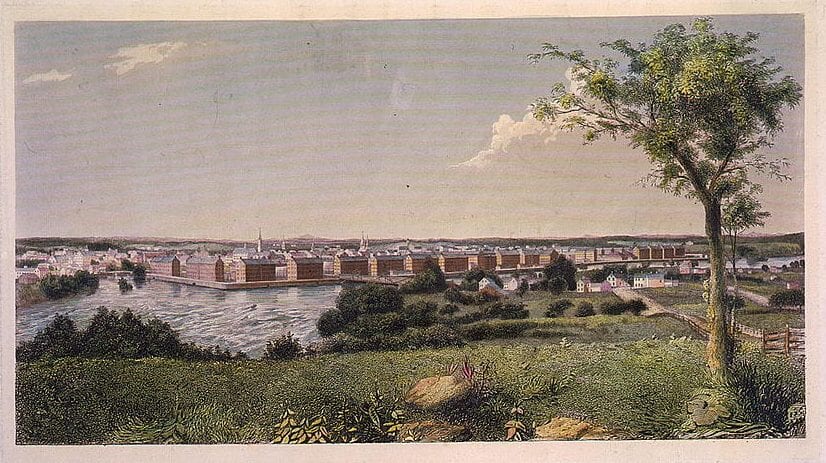

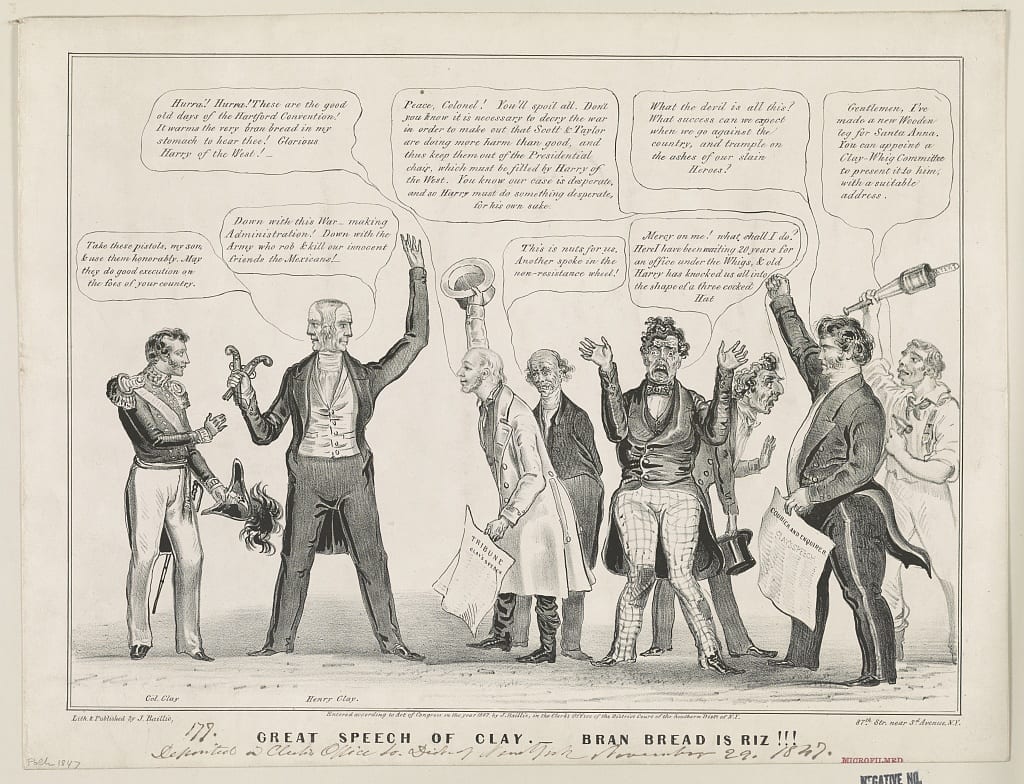

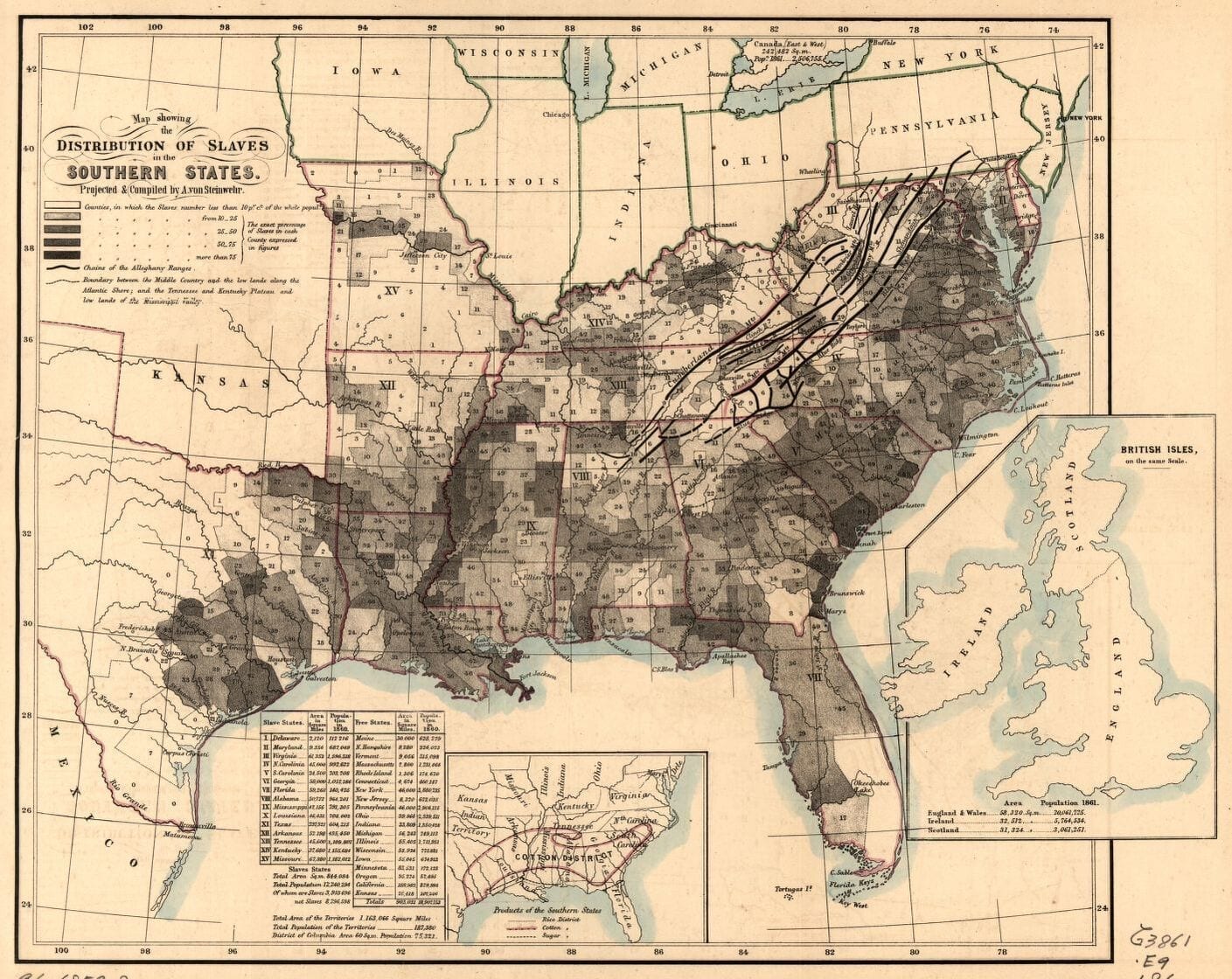

Although the 1803 Marbury v. Madison decision helped claim for the Supreme Court the power to declare laws unconstitutional, the idea that the states had a legitimate ability to weigh in on the constitutionality of federal measures (previously manifested in the Hartford Convention) gained ground in the 1820s, particularly in the agricultural South, where people viewed national economic policies as unfairly partial toward northern manufacturing. South Carolinians took the lead in protesting the federal “tariff of abominations” in 1828.

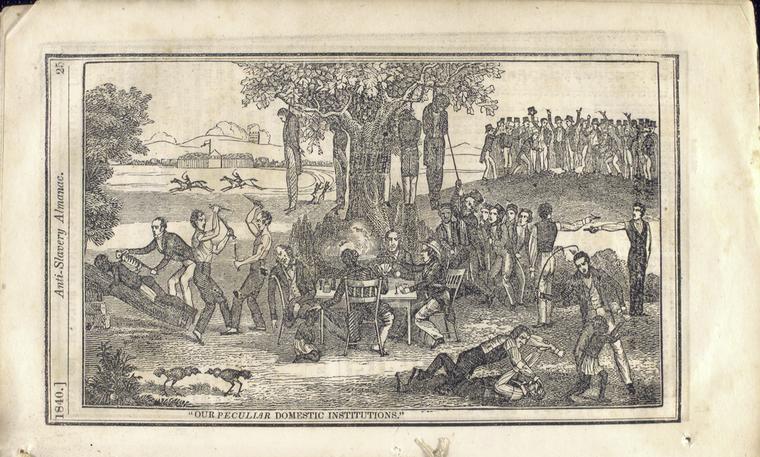

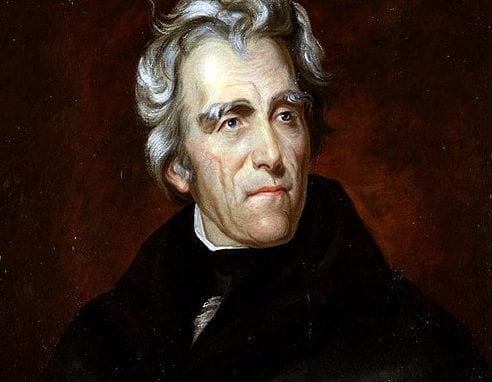

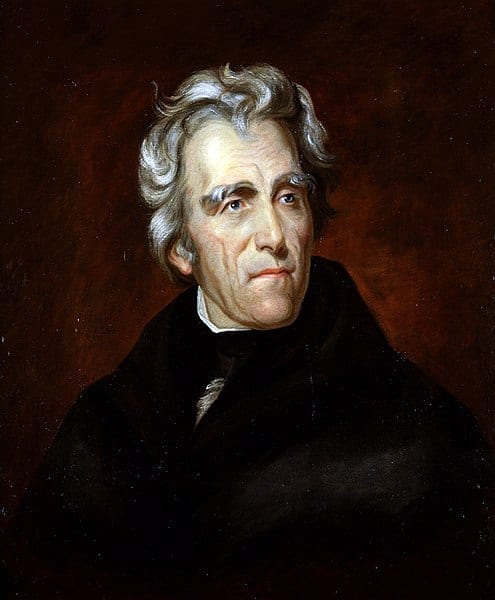

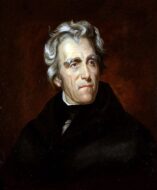

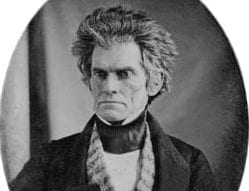

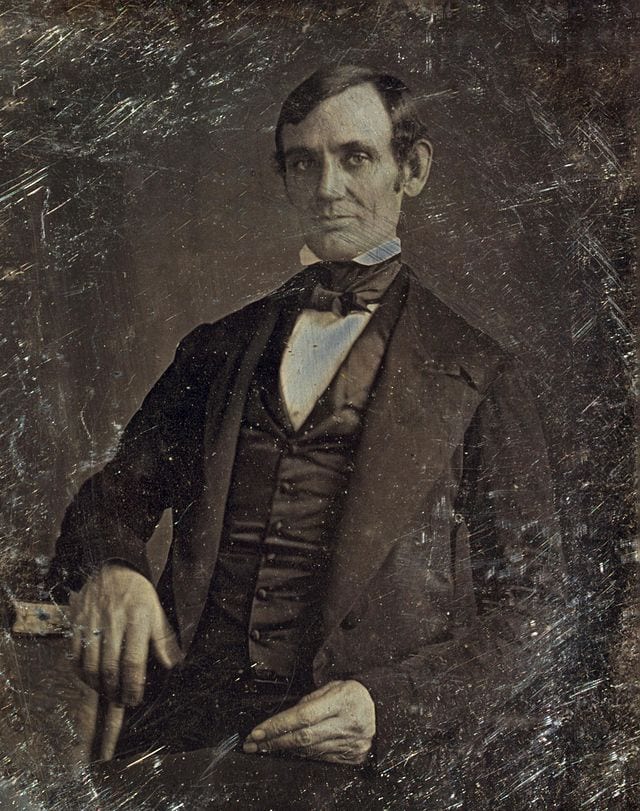

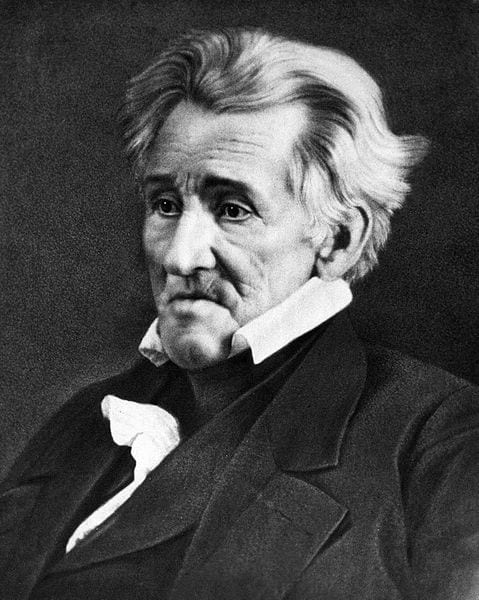

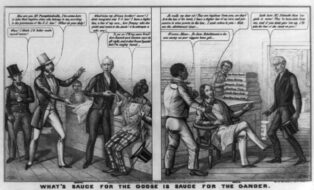

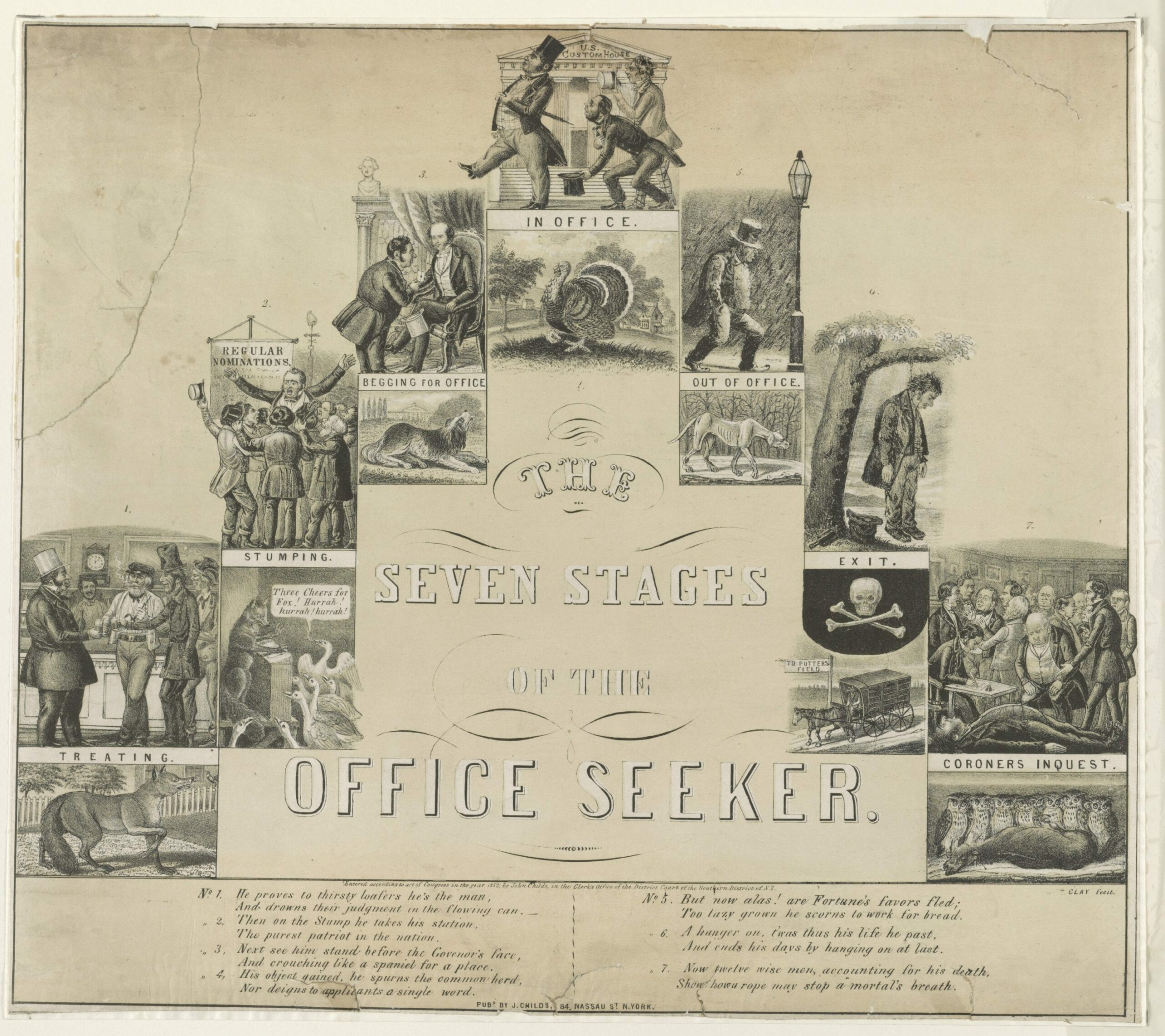

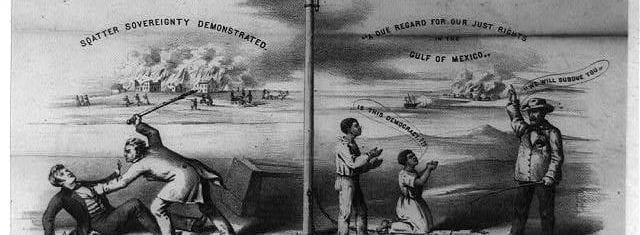

President Andrew Jackson publicly refuted all arguments in favor of nullification, and brought a swift end to South Carolina’s rhetorical rebellion by threatening to use military force against the state if it did not comply with federal law. Many Northerners believed that nullification was not only a philosophical absurdity, but also directly linked to the perpetuation of the institution of slavery. They applauded Jackson’s actions as a defense of not only the Union, but also of freedom itself. The theory of state sovereignty at the heart of nullification continued to appeal to many Americans and contributed to the deepening divide between northerners and southerners during the antebellum period, leading at least one pessimistic wag to pen an “Epitaph for the Constitution” in which he (or she) imagined the issue leading to the collapse of the Union.

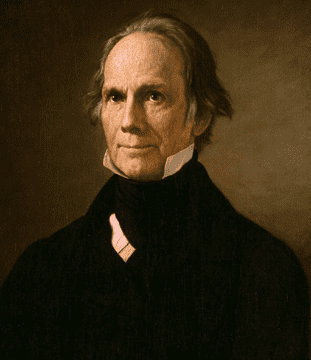

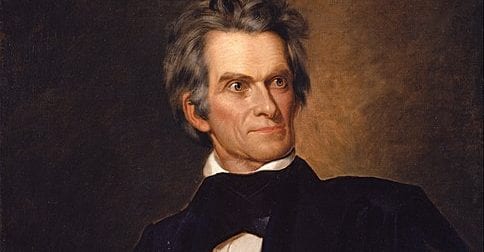

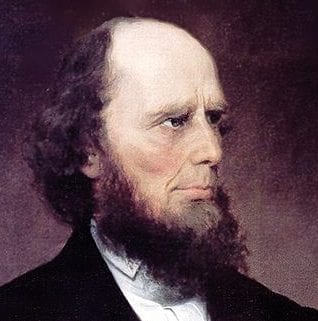

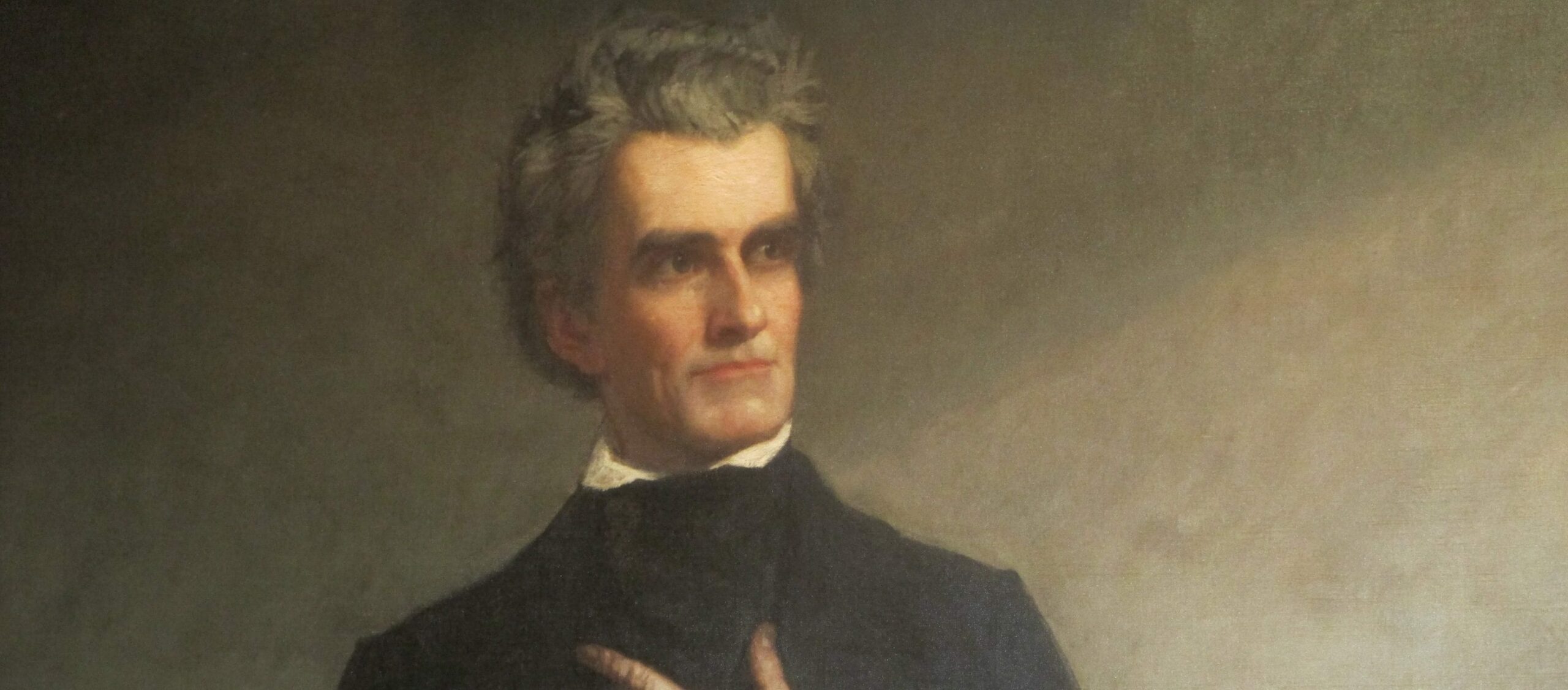

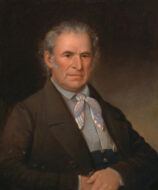

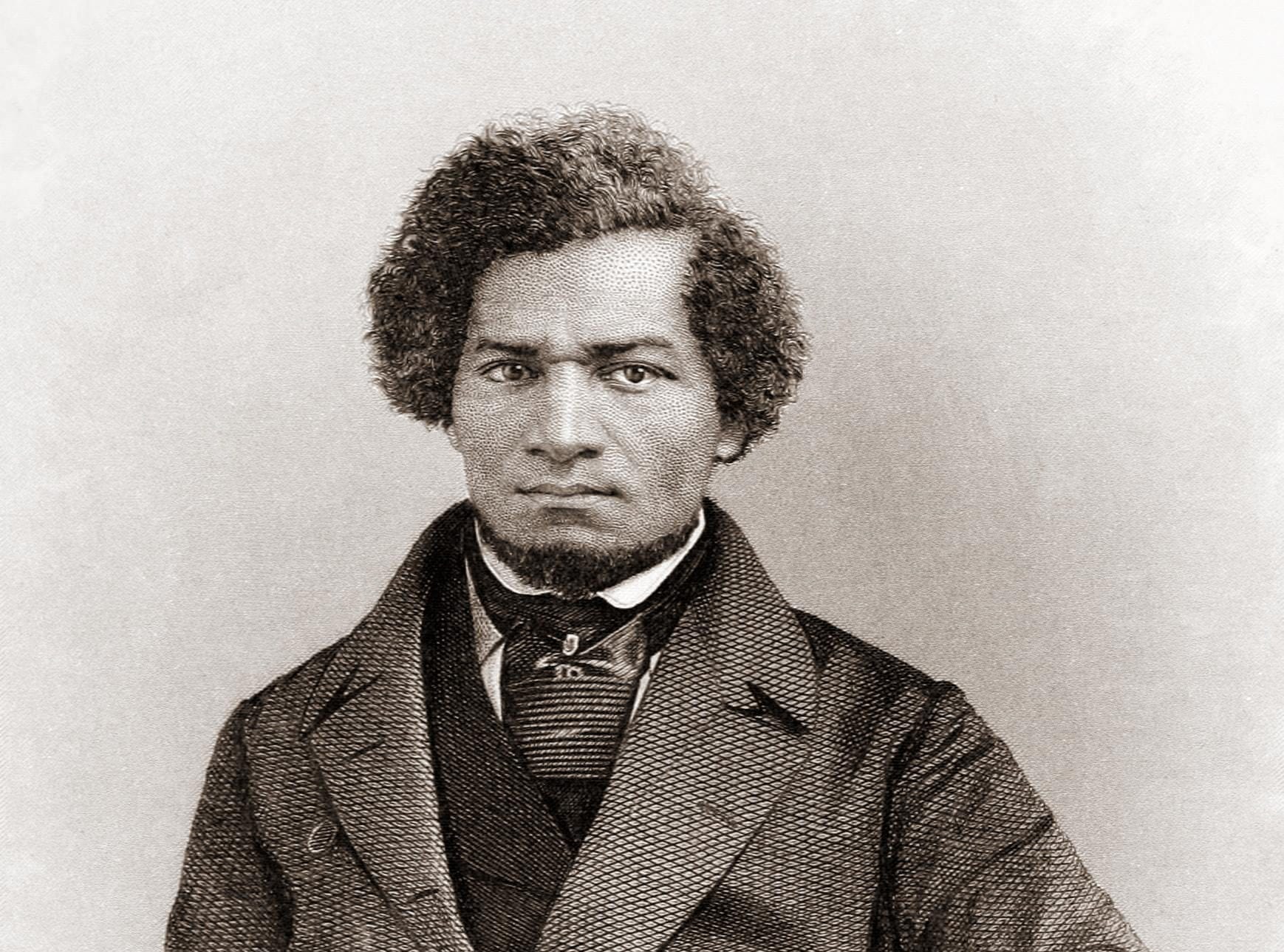

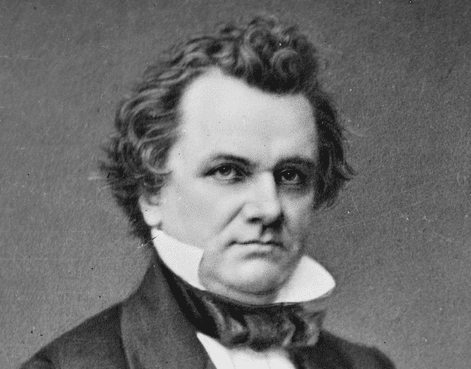

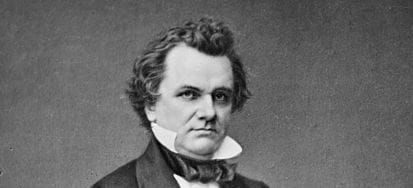

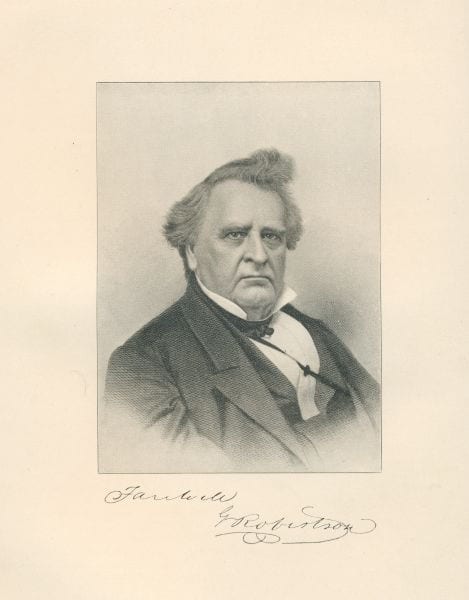

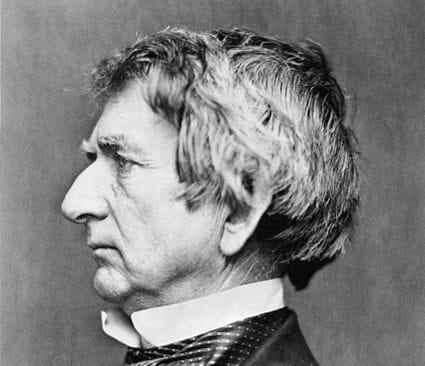

The Webster-Hayne Debate on the Nature of the Constitution: Selected Documents, ed. Herman Belz (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000). 3/26/2018. Available online at: https://goo.gl/7Pbesa. Robert Y. Hayne (1791–1839) was a U.S. senator from South Carolina.

. . . [W]e ask nothing of our Northern brethren but to “let us alone;” leave us to the undisturbed management of our domestic concerns, and the direction of our own industry, and we will ask no more. . . .

The honorable gentleman from Massachusetts [Mr. Webster1] while he exonerates me personally from the charge, intimates that there is a party in the country who are looking to disunion. . . . Sir, when the gentleman provokes me to such a conflict, I meet him at the threshold. I will struggle while I have life, for our altars and our fire sides, and if God gives me strength, I will drive back the invader discomfited. Nor shall I stop there. If the gentleman provokes the war, he shall have war. Sir, I will not stop at the border; I will carry the war into the enemy’s territory, and not consent to lay down my arms, until I shall have obtained “indemnity for the past, and security for the future.”2 It is with unfeigned reluctance that I enter upon the performance of this part of my duty. I shrink almost instinctively from a course, however necessary, which may have a tendency to excite sectional feelings, and sectional jealousies. But, sir, the task has been forced upon me, and I proceed right onward to the performance of my duty; be the consequences what they may, the responsibility is with those who have imposed upon me this necessity. . . .

Who, then, Mr. President, are the true friends of the Union? Those who would confine the federal government strictly within the limits prescribed by the constitution – who would preserve to the States and the people all powers not expressly delegated – who would make this a federal and not a national Union – and who, administering the government in a spirit of equal justice, would make it a blessing and not a curse. And who are its enemies? Those who are in favor of consolidation; who are constantly stealing power from the States and adding strength to the federal government; who, assuming an unwarrantable jurisdiction over the States and the people, undertake to regulate the whole industry and capital of the country. . . .

The Senator from Massachusetts, in denouncing what he is pleased to call the Carolina doctrine, has attempted to throw ridicule upon the idea that a State has any constitutional remedy by the exercise of its sovereign authority against “a gross, palpable, and deliberate violation of the Constitution.” He called it “an idle” or “a ridiculous notion,” or something to that effect; and added, that it would make the Union “a mere rope of sand”. . . .

Sir, as to the doctrine that the Federal Government is the exclusive judge of the extent as well as the limitations of its powers, it seems to be utterly subversive of the sovereignty and independence of the States. It makes but little difference, in my estimation, whether Congress or the Supreme Court, are invested with this power. If the Federal Government, in all or any of its departments, are to prescribe the limits of its own authority; and the States are bound to submit to the decision, and are not to be allowed to examine and decide for themselves, when the barriers of the Constitution shall be overleaped, this is practically “a Government without limitation of powers;” the States are at once reduced to mere petty corporations, and the people are entirely at your mercy. I have but one word more to add. In all the efforts that have been made by South Carolina to resist the unconstitutional laws which Congress has extended over them, she has kept steadily in view the preservation of the Union, by the only means by which she believes it can be long preserved – a firm, manly, and steady resistance against usurpation. The measures of the Federal Government have, it is true, prostrated her interests, and will soon involve the whole South in irretrievable ruin. . . .

. . . It cannot be doubted, and is not denied, that before the formation of the constitution, each State was an independent sovereignty, possessing all the rights and powers appertaining to independent nations; nor can it be denied that, after the constitution was formed, they remained equally sovereign and independent, as to all powers, not expressly delegated to the Federal Government. This would have been the case even if no positive provision to that effect had been inserted in that instrument. But to remove all doubt it is expressly declared, by the 10th article of the amendment of the constitution, “that the powers not delegated to the States, by the constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”. . .

The whole form and structure of the Federal Government, the opinions of the framers of the Constitution, and the organization of the State Governments, demonstrate that though the States have surrendered certain specific powers, they have not surrendered their sovereignty. . . .

No doubt can exist, that, before the States entered into the compact, they possessed the right to the fullest extent, of determining the limits of their own powers – it is incident to all sovereignty. Now, have they given away that right, or agreed to limit or restrict it in any respect? Assuredly not. They have agreed, that certain specific powers shall be exercised by the Federal Government; but the moment that Government steps beyond the limits of its charter, the right of the States “to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits the authorities, rights, and liberties, appertaining to them,”3 is as full and complete as it was before the Constitution was formed. It was plenary then, and never having been surrendered, must be plenary now.

. . .

The gentleman has made an eloquent appeal to our hearts in favor of union. Sir, I cordially respond to that appeal. I will yield to no gentleman here in sincere attachment to the Union, – but it is a Union founded on the Constitution, and not such a Union as that gentleman would give us, that is dear to my heart. If this is to become one great “consolidated government,” swallowing up the rights of the States, and the liberties of the citizen, “riding and ruling over the plundered ploughman, and beggared yeomanry,”4 the Union will not be worth preserving. Sir, it is because South Carolina loves the Union, and would preserve it forever, that she is opposing now, while there is hope, those usurpations of the Federal Government, which, once established, will, sooner or later, tear this Union into fragments. . . .

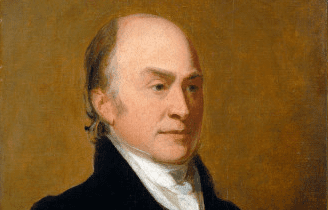

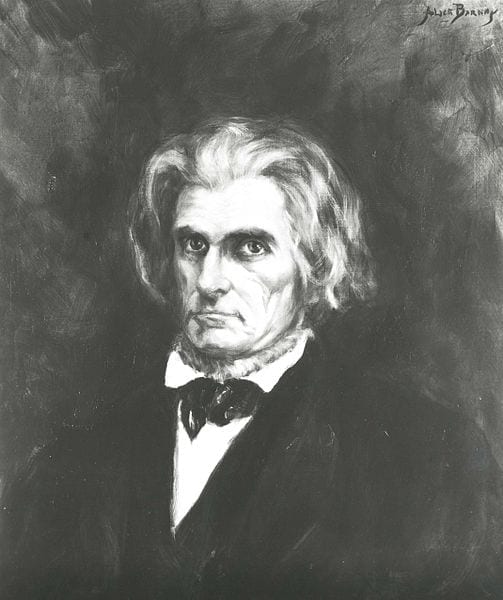

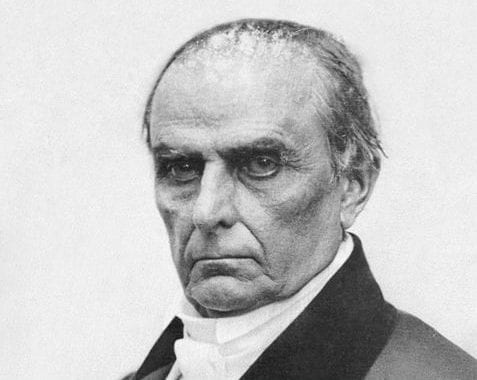

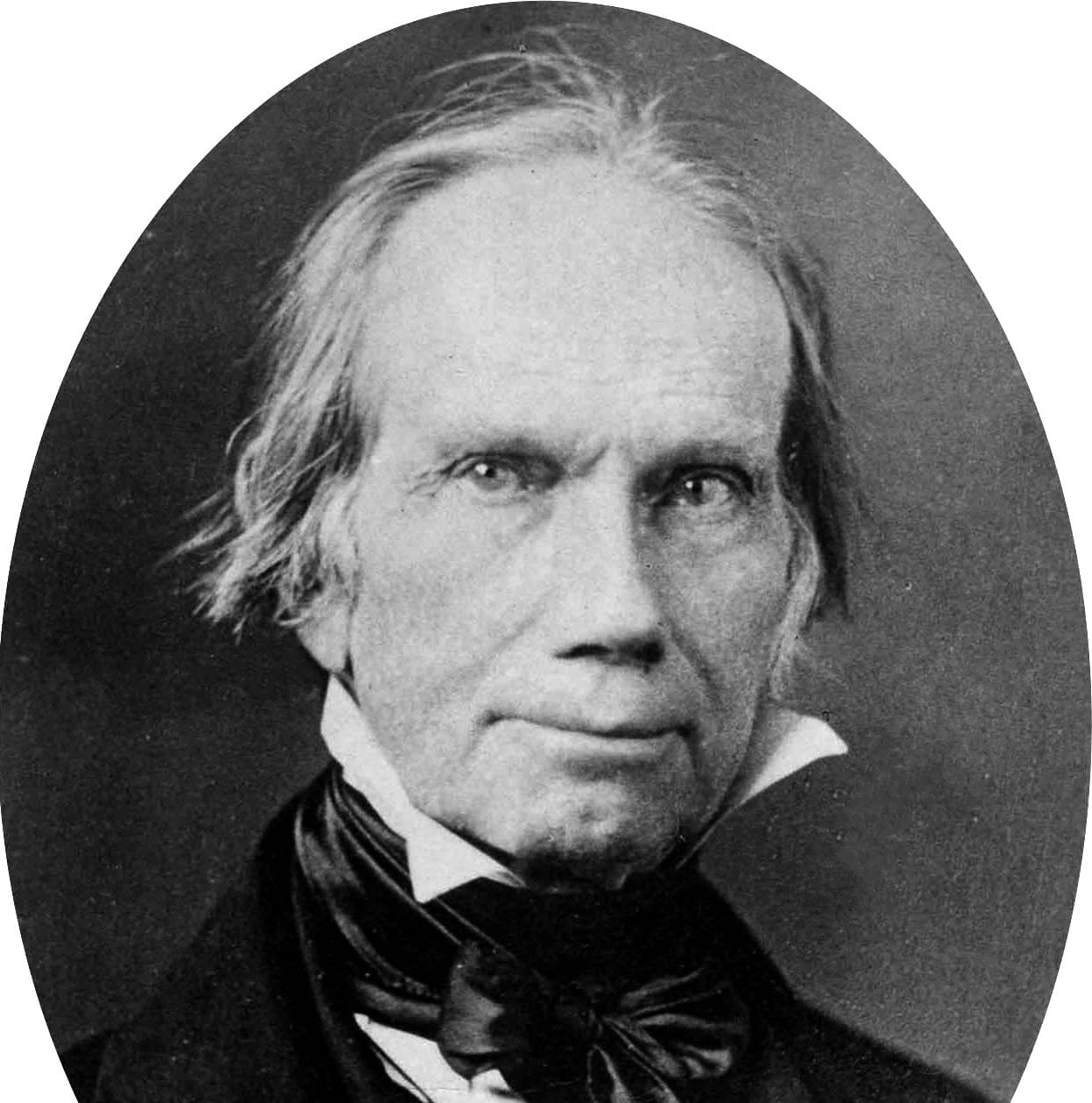

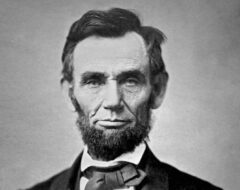

- 1. Daniel Webster (1782–1852) was a lawyer, U.S. senator from Massachusetts and a secretary of state.

- 2. A phrase used subsequently in American history with regard to Mexico and the defeated South, which appears to have originated in British Parliamentary debate with reference to Britain’s attitude toward the American colonies.

- 3. A quotation from the Virginia Resolves, written by James Madison.

- 4. A quotation from a letter of Thomas Jefferson to William Branch Giles, (December 26, 1825) criticizing a consolidated federal government.

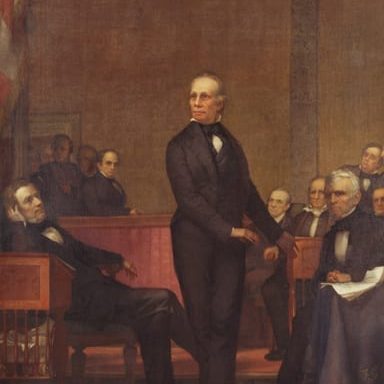

The Webster-Hayne Debates

January, 1830

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.