No related resources

Introduction

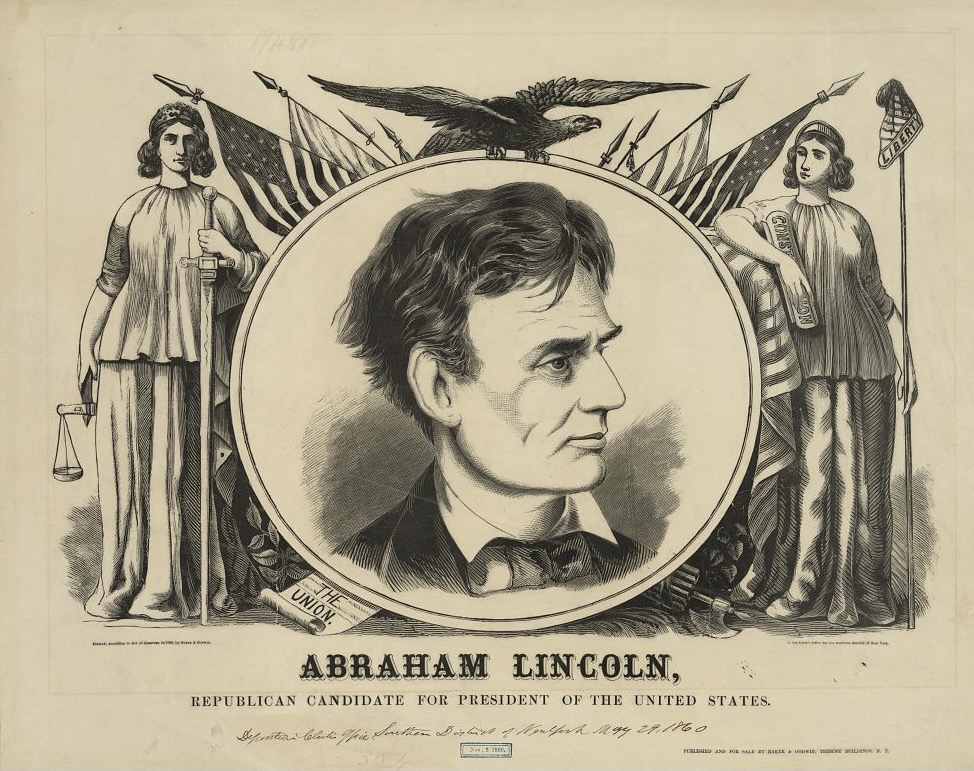

Lincoln’s Speech at Chicago responded to remarks made the day before by Stephen A. Douglas (1813–1861), the incumbent against whom he was running for the Senate. Douglas claimed that Lincoln’s House Divided Speech was a “great political heresy” that invited sectional war and destroyed the division of power between the federal and state governments, forcing the states into uniformity “in all their internal regulations.” Lincoln’s speech anticipated many of the arguments he made in the debates with Douglas the following fall during the Senate campaign.

In the first section, Lincoln humorously defended the Republican Party from Douglas’ accusation that it was “an unholy and unnatural alliance” of radicals. He then investigated the principle of “popular sovereignty,” tracing its origin to the Declaration of Independence rather than to Douglas’ policy for dealing with slavery in the territories. In the final part of the first section, Lincoln revealed the contradiction between Dred Scott’s ruling that slavery could not be excluded from the territories and popular sovereignty’s guarantee that territorial settlers could restrict slavery if they so desired. Citing this contradiction, Lincoln discredited Douglas as an antislavery candidate, even though he had opposed the proslavery Lecompton Constitution under which Kansas sought to be admitted as a new state. Douglas had opposed the constitution because of fraudulent voting rather than any principled opposition to slavery. Lincoln emphasized that the Republican Party, not the minority faction of Douglas Democrats, deserved credit for defeating Lecompton and for carrying the antislavery banner forward.

In the second section, Lincoln attacked Douglas for his indifference to the “vast moral evil” of slavery. Lincoln also denied that his opposition to Dred Scott constituted “resistance” to the rule of law. Here Lincoln cited the example of President Andrew Jackson, the former head of the Democratic Party, who argued that each branch of the federal government had a duty to uphold the Constitution as each interpreted it. In the final section Lincoln affirmed equality as “the father of all moral principle,” the Declaration as the “electric cord” uniting the hearts of liberty-loving patriots in the Union. He warned that the principle of slavery would not stop with African Americans but would eventually threaten the freedom of whites as well. Seeking to explain how the principle of equality might serve as a moral and political standard notwithstanding its current contradiction by the existence of slavery, Lincoln offered an interpretation of Bible verse, “As your Father in Heaven is perfect, be ye also perfect” (Matthew 5:48). Lincoln concluded with a rousing peroration that “all men are created free and equal.”

Source: Life and Works of Abraham Lincoln, Centenary Edition, vol. 3, ed. Marion MillsMiller (New York: Current Literature Publishing, 1907), 47–72, https://archive.org/details/lifeworks03lincuoft/page/n3.

My Fellow Citizens:

On yesterday evening, upon the occasion of the reception given to Senator Douglas, I was furnished with a seat very convenient for hearing him, and was otherwise very courteously treated by him and his friends, and for which I thank him and them. During the course of his remarks my name was mentioned in such a way as, I suppose, renders it at least not improper that I should make some sort of reply to him. I shall not attempt to follow him in the precise order in which he addressed the assembled multitude upon that occasion, though I shall perhaps do so in the main.

There was one question to which he asked the attention of the crowd, which I deem of somewhat less importance—at least of propriety for me to dwell upon—than the others, which he brought in near the close of his speech, and which I think it would not be entirely proper for me to omit attending to; and yet if I were not to give some attention to it now, I should probably forget it altogether. While I am upon this subject, allow me to say that I do not intend to indulge in that inconvenient mode sometimes adopted in public speaking, of reading from documents; but I shall depart from that rule so far as to read a little scrap from his speech, which notices this first topic of which I shall speak—that is, provided I can find it in the paper.

I have made up my mind to appeal to the people against the combination that has been made against me. The Republican leaders have formed an alliance, an unholy and unnatural alliance,1 with a portion of unscrupulous federal office-holders. I intend to fight that allied army wherever I meet them. I know they deny the alliance, but yet these men who are trying to divide the Democratic party for the purpose of electing a Republican senator in my place, are just so much the agents and tools of the supporters of Mr. Lincoln. Hence I shall deal with this allied army just as the Russians dealt with the allies at Sebastopol—that is, the Russians did not stop to inquire, when they fired a broadside, whether it hit an Englishman, a Frenchman, or a Turk. Nor will I stop to inquire, nor shall I hesitate, whether my blows shall hit these Republican leaders or their allies, who are holding the federal offices and yet acting in concert with them.

Well, now, gentlemen, is not that very alarming? Just to think of it! right at the outset of his canvass, I, a poor, kind, amiable, intelligent gentleman—I am to be slain in this way. Why, my friend the Judge is not only, as it turns out, not a dead lion, nor even a living one—he is the rugged Russian bear.

But if they will have it—for he says that we deny it—that there is any such alliance, as he says there is—and I don’t propose hanging very much upon this question of veracity—but if he will have it that here is such an alliance, that the administration men and we are allied, and we stand in the attitude of English, French, and Turk, he occupying the position of the Russian—in that case I beg he will indulge us while we barely suggest to him that these allies took Sebastopol.

Gentlemen, only a few more words as to this alliance. For my part, I have to say that whether there be such an alliance depends, so far as I know, upon what may be a right definition of the term “alliance.” If for the Republican party to see the other great party to which they are opposed divided among themselves and not try to stop the division, and rather be glad of it—if that is an alliance, I confess I am in; but if it is meant to be said that the Republicans had formed an alliance going beyond that, by which there is contribution of money or sacrifice of principle on the one side or the other, so far as the Republican party is concerned, if there be any such thing, I protest that I neither know anything of it nor do I believe it. I will however, say—as I think this branch of the argument is lugged in—I would before I leave it state, for the benefit of those concerned, that one of those same Buchanan2 men did once tell me of an argument that he made for his opposition to Judge Douglas.3 He said that a friend of our Senator Douglas had been talking to him, and had among other things said to him: “Why, you don’t want to beat Douglas?” “Yes,” said he,

I do want to beat him, and I will tell you why. I believe his original Nebraska bill was right in the abstract, but it was wrong in the time that it was brought forward. It was wrong in the application to a territory in regard to which the question had been settled; it was brought forward at a time when nobody asked him; it was tendered to the South when the South had not asked for it, but when they could not well refuse it; and for this same reason he forced that question upon our party. It has sunk the best men all over the nation, everywhere; and now when our president, struggling with the difficulties of this man’s getting up, has reached the very hardest point to turn in the case, he deserts him, and I am for putting him where he will trouble us no more.

Now, gentlemen, that is not my argument—that is not my argument at all. I have only been stating to you the argument of a Buchanan man. You will judge if there is any force in it.

Popular sovereignty! everlasting popular sovereignty! Let us for a moment inquire into this vast matter of popular sovereignty. What is popular sovereignty? We recollect that at an early period in the history of this struggle, there was another name for the same thing—squatter sovereignty. It was not exactly popular sovereignty, but squatter sovereignty. What did those terms mean? What do those terms mean when used now? And vast credit is taken by our friend the Judge in regard to his support of it, when he declares the last years of his life have been, and all the future years of his life shall be, devoted to this matter of popular sovereignty. What is it? Why, it is the sovereignty of the people! What was squatter sovereignty? I suppose if it had any significance at all, it was the right of the people to govern themselves, to be sovereign in their own affairs while they were squatted down in a country not their own, while they had squatted on a territory that did not belong to them, in the sense that a state belongs to the people who inhabit it—when it belonged to the nation—such right to govern themselves was called “squatter sovereignty.”

Now I wish you to mark what has become of that squatter sovereignty. What has become of it? Can you get anybody to tell you now that the people of a territory have any authority to govern themselves, in regard to this mooted question of slavery, before they form a state constitution? No such thing at all, although there is a general running fire, and although there has been a hurrah made in every speech on that side, assuming that policy had given the people of a territory the right to govern themselves upon this question; yet the point is dodged. Today it has been decided—no more than a year ago it was decided by the Supreme Court of the United States,4 and is insisted upon today—that the people of a territory have no right to exclude slavery from a territory; that if any one man chooses to take slaves into a territory, all the rest of the people have no right to keep them out. This being so, and this decision being made one of the points that the Judge approved, and one in the approval of which he says he means to keep me down—put me down I should not say, for I have never been up; he says he is in favor of it, and sticks to it, and expects to win his battle on that decision, which says that there is no such thing as squatter sovereignty, but that any one man may take slaves into a territory, and all the other men in the territory may be opposed to it, and yet by reason of the Constitution they cannot prohibit it. When that is so, how much is left of this vast matter of squatter sovereignty, I should like to know?

When we get back, we get to the point of the right of people to make a constitution. Kansas was settled, for example, in 1854. It was a territory yet, without having formed a constitution, in a very regular way, for three years. All this time negro slavery could be taken in by any few individuals, and by that decision of the Supreme Court, which the Judge approves, all the rest of the people cannot keep it out; but when they come to make a constitution they may say they will not have slavery. But it is there; they are obliged to tolerate it some way, and all experience shows it will be so—for they will not take the negro slaves and absolutely deprive the owners of them. All experience shows this to be so. All that space of time that runs from the beginning of the settlement of the territory until there is sufficiency of people to make a state constitution—all that portion of time popular sovereignty is given up. The seal is absolutely put down upon it by the court decision, and Judge Douglas puts his own upon the top of that; yet he is appealing to the people to give him vast credit for his devotion to popular sovereignty.

Again, when we get to the question of the right of the people to form a state constitution as they please, to form it with slavery or without slavery—if that is anything new, I confess I don’t know it. Has there ever been a time when anybody said that any other than the people of a territory itself should form a constitution? What is now in it that Judge Douglas should have fought several years of his life, and pledge himself to fight all the remaining years of his life, for? Can Judge Douglas find anybody on earth that said that anybody else should form a constitution for a people? (A voice: “Yes.”) Well, I should like you to name him; I should like to know who he was. (Same voice: “John Calhoun.”) No, sir; I never heard of even John Calhoun5 saying such a thing. He insisted on the same principle as Judge Douglas; but his mode of applying it, in fact, was wrong. It is enough for my purpose to ask this crowd whenever a Republican said anything against it? They never said anything against it, but they have constantly spoken for it; and whosoever will undertake to examine the platform and the speeches of responsible men of the party, and of irresponsible men, too, if you please, will be unable to find one word from anybody in the Republican ranks opposed to that popular sovereignty which Judge Douglas thinks he has invented. I suppose that Judge Douglas will claim in a little while that he is the inventor of the idea that the people should govern themselves; that nobody ever thought of such a thing until he brought it forward. We do not remember that in that old Declaration of Independence it is said that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” There is the origin of popular sovereignty. Who, then, shall come in at this day and claim that he invented it?

The Lecompton Constitution connects itself with this question, for it is in this matter of the Lecompton Constitution that our friend Judge Douglas claims such vast credit. I agree that in opposing the Lecompton Constitution, so far as I can perceive, he was right. I do not deny that at all; and, gentlemen, you will readily see why I could not deny it, even if I wanted to. But I do not wish to; for all the Republicans in the nation opposed it, and they would have opposed it just as much without Judge Douglas’ aid as with it. They had all taken ground against it long before he did. Why, the reason that he urges against that constitution I urged against him a year before. I have the printed speech in my hand. The argument that he makes why that constitution should not be adopted, that the people were not fairly represented nor allowed to vote, I pointed out in a speech a year ago, which I hold in my hand now, that no fair chance was to be given to the people. (“Read it; read it.”) I shall not waste your time by trying to read it. (“Read it; read it.”) Gentlemen, reading from speeches is a very tedious business, particularly for an old man who has to put on spectacles, and more so if the man be so tall that he has to bend over to the light.

A little more now as to this matter of popular sovereignty and the Lecompton Constitution. The Lecompton Constitution, as the Judge tells us, was defeated. The defeat of it was a good thing, or it was not. He thinks the defeat of it was a good thing, and so do I, and we agree in that. Who defeated it? (A voice: “Judge Douglas.”) Yes, he furnished himself, and if you suppose he controlled the other Democrats that went with him, he furnished three votes, while the Republicans furnished twenty.

That is what he did to defeat it. In the House of Representatives he and his friends furnished some twenty votes, and the Republicans furnished ninety odd. Now, who was it that did the work? (A voice: “Douglas.”) Why, yes, Douglas did it? To be sure he did.

Let us, however, put that proposition another way. The Republicans could not have done it without Judge Douglas. Could he have done it without them? Which could have come the nearest to doing it without the other? (A voice: “Who killed the bill?” Another voice: “Douglas.”) Ground was taken against it by the Republicans long before Douglas did it. The proportion of opposition to that measure is about five to one. (A voice: “Why don’t they come out on it?”) You don’t know what you are talking about, my friend. I am quite willing to answer any gentleman in the crowd who asks an intelligent question.

Now, who, in all this country, has ever found any of our friends of Judge Douglas’ way of thinking, and who have acted upon this main question, that have ever thought of uttering a word in behalf of Judge Trumbull?6 (A voice: “We have.”) I defy you to show a printed resolution passed in a Democratic meeting. I take it upon myself to defy any man to show a printed resolution of a Democratic meeting, large or small, in favor of Judge Trumbull, or any of the five-to-one Republicans who beat that bill. Everything must be for the Democrats! They did everything, and the five to the one that really did the thing they snub over, and they do not seem to remember that they have an existence upon the face of the earth.

Gentlemen, I fear that I shall become tedious. I leave this branch of the subject to take hold of another. I take up that part of Judge Douglas’ speech in which he respectfully attended to me.

Judge Douglas made two points upon my recent speech at Springfield.7 He says they are to be the issues of this campaign. The first one of these points he bases upon the language in a speech which I delivered at Springfield, which I believe I can quote correctly from memory. I said there that “we are now far into the fifth year since a policy was instituted for the avowed object and with the confident promise of putting an end to slavery agitation; under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only not ceased, but has constantly augmented. I believe it will not cease until a crisis shall have been reached and passed. ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’8 I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved”—I am quoting from my speech—“I do not expect the house to fall, but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward until it shall become alike lawful in all the states, old as well as new, North as well as South.”

That is the paragraph! In this paragraph which I have quoted in your

hearing, and to which I ask the attention of all, Judge Douglas thinks he discovers great political heresy. I want your attention particularly to what he has inferred from it. He says I am in favor of making all the states of this Union uniform in all their internal regulations; that in all their domestic concerns I am in favor of making them entirely uniform. He draws this inference from the language I have quoted to you. He says that I am in favor of making war by the North upon the South for the extinction of slavery; that I am also in favor of inviting (as he expresses it) the South to a war upon the North, for the purpose of nationalizing slavery. Now, it is singular enough, if you will carefully read that passage over, that I did not say that I was in favor of anything in it. I only said what I expected would take place. I made a prediction only—it may have been a foolish one, perhaps. I did not even say that I desired that slavery should be put in course of ultimate extinction. I do say so now, however, so there need be no longer any difficulty about that. It may be written down in the great speech.

Gentlemen, Judge Douglas informed you that this speech of mine was probably carefully prepared. I admit that it was. I am not master of language; I have not a fine education; I am not capable of entering into a disquisition upon dialectics, as I believe you call it; but I do not believe the language I employed bears any such construction as Judge Douglas puts upon it. But I don’t care about a quibble in regard to words. I know what I meant, and I will not leave this crowd in doubt, if I can explain it to them, what I really meant in the use of that paragraph.

I am not, in the first place, unaware that this government has endured eighty-two years half slave and half free. I know that. I am tolerably well acquainted with the history of the country, and I know that it has endured eighty-two years half slave and half free. I believe—and that is what I meant to allude to there—I believe it has endured because during all that time, until the introduction of the Nebraska bill, the public mind did rest all the time in the belief that slavery was in course of ultimate extinction. That was what gave us the rest that we had through that period of eighty-two years; at least, so I believe. I have always hated slavery, I think, as much as any abolitionist—I have been an old-line Whig9—I have always hated it, but I have always been quiet about it until this new era of the introduction of the Nebraska bill began. I always believed that everybody was against it, and that it was in course of ultimate extinction. (Pointing to Mr. Browning,10 who stood nearby.) Browning thought so; the great mass of the nation have rested in the belief that slavery was in course of ultimate extinction. They had reason so to believe.

The adoption of the Constitution and its attendant history led the people to believe so, and that such was the belief of the framers of the Constitution itself. Why did those old men, about the time of the adoption of the Constitution, decree that slavery should not go into the new territory, where it had not already gone? Why declare that within twenty years the African slave trade, by which slaves are supplied, might be cut off by Congress? Why were all these acts? I might enumerate more of these acts—but enough. What were they but a clear indication that the framers of the Constitution intended and expected the ultimate extinction of that institution? And now, when I say—as I said in my speech that Judge Douglas has quoted from—when I say that I think the opponents of slavery will resist the farther spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in course of ultimate extinction, I only mean to say that they will place it where the founders of this government originally placed it.

I have said a hundred times, and I have now no inclination to take it back, that I believe there is no right and ought to be no inclination in the people of the free states to enter into the slave states and interfere with the question of slavery at all. I have said that always; Judge Douglas has heard me say it—if not quite a hundred times, at least as good as a hundred times; and when it is said that I am in favor of interfering with slavery where it exists, I know it is unwarranted by anything I have ever intended, and, as I believe, by anything I have ever said. If by any means I have ever used language which could fairly be so construed (as, however, I believe I never have), I now correct it.

So much, then, for the inference that Judge Douglas draws, that I am in favor of setting the sections at war with one another. I know that I never meant any such thing, and I believe that no fair mind can infer any such thing from anything I have ever said.

Now in relation to his inference that I am in favor of a general consolidation of all the local institutions of the various states. I will attend to that for a little while, and try to inquire, if I can, how on earth it could be that any man could draw such an inference from anything I said. I have said very many times in Judge Douglas’ hearing that no man believed more than I in the principle of self-government; that it lies at the bottom of all my ideas of just government from beginning to end. I have denied that his use of that term applies properly. But for the thing itself I deny that any man has ever gone ahead of me in his devotion to the principle, whatever he may have done in efficiency in advocating it. I think that I have said it in your hearing—that I believe each individual is naturally entitled to do as he pleases with himself and the fruit of his labor, so far as it in no wise interferes with any other man’s rights; that each community, as a state, has a right to do exactly as it pleases with all the concerns within that state that interfere with the right of no other state; and that the general government, upon principle, has no right to interfere with anything other than that general class of things that does not concern the whole. I have said that at all times. I have said as illustrations that I do not believe in the right of Illinois to interfere with the cranberry laws of Indiana, the oyster laws of Virginia, or the liquor laws of Maine. I have said these things over and over again, and I repeat them here as my sentiments.11

How is it, then, that Judge Douglas infers, because I hope to see slavery put where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, that I am in favor of Illinois going over and interfering with the cranberry laws of Indiana? What can authorize him to draw any such inference? I suppose there might he one thing that at least enabled him to draw such an inference that would not be true with me or many others; that is, because he looks upon all this matter of slavery as an exceedingly little thing—this matter of keeping one sixth of the population of the whole nation in a state of oppression and tyranny unequaled in the world. He looks upon it as being an exceedingly little thing, only equal to the question of the cranberry laws of Indiana—as something having no moral question in it—as something on a par with the question of whether a man shall pasture his land with cattle or plant it with tobacco—so little and so small a thing that he concludes, if I could desire that anything should be done to bring about the ultimate extinction of that little thing, I must be in favor of bringing about an amalgamation of all the other little things in the Union. Now, it so happens—and there, I presume, is the foundation of this mistake—that the Judge thinks thus; and it so happens that there is a vast portion of the American people that do not look upon that matter as being this very little thing. They look upon it as a vast moral evil; they can prove it as such by the writings of those who gave us the blessings of liberty which we enjoy, and that they so looked upon it, and not as an evil merely confining itself to the states where it is situated; and while we agree that, by the Constitution we assented to, in the states where it exists we have no right to interfere with it, because it is in the Constitution, we are by both duty and inclination to stick by that Constitution in all its letter and spirit from beginning to end.

So much, then, as to my disposition—my wish—to have all the state legislatures blotted out, and to have one consolidated government, and a uniformity of domestic regulations in all the states; by which I suppose it is meant, if we raise corn here, we must make sugarcane grow here too, and we must make those which grow North grow in the South. All this I suppose he understands I am in favor of doing. Now, so much for all this nonsense—for I must call it so. The Judge can have no issue with me on a question of establishing uniformity in the domestic regulations of the states.

A little now on the other point—the Dred Scott decision. Another of the issues he says that is to be made with me, is upon his devotion to the Dred Scott decision, and my opposition to it.

I have expressed heretofore, and I now repeat, my opposition to the Dred Scott decision; but I should be allowed to state the nature of that opposition, and I ask your indulgence while I do so. What is fairly implied by the term Judge Douglas has used, “resistance to the decision”? I do not resist it. If I wanted to take Dred Scott from his master, I would be interfering with property, and that terrible difficulty that Judge Douglas speaks of, of interfering with property, would arise. But I am doing no such thing as that; all that I am doing is refusing to obey it as a political rule. If I were in Congress, and a vote should come up on a question whether slavery should be prohibited in a new territory, in spite of the Dred Scott decision, I would vote that it should.

That is what I would do. Judge Douglas said last night that before the decision he might advance his opinion, and it might be contrary to the decision when it was made; but after it was made he would abide by it until it was reversed. Just so! We let this property abide by the decision, but we will try to reverse that decision. We will try to put it where Judge Douglas would not object, for he says he will obey it until it is reversed. Somebody has to reverse that decision, since it is made; and we mean to reverse it, and we mean to do it peaceably.

What are the uses of decisions of courts? They have two uses. As rules of property they have two uses. First—they decide upon the question before the Court. They decide in this case that Dred Scott is a slave. Nobody resists that. Not only that, but they say to everybody else that persons standing just as Dred Scott stands are as he is. That is, they say that when a question comes up upon another person, it will be so decided again, unless the Court decides in another way, unless the Court overrules its decision. Well, we mean to do what we can to have the Court decide the other way. That is one thing we mean to try to do.

The sacredness that Judge Douglas throws around this decision is a degree of sacredness that has never been before thrown around any other decision. I have never heard of such a thing. Why, decisions apparently contrary to that decision, or that good lawyers thought were contrary to that decision, have been made by that very Court before. It is the first of its kind; it is an astonisher in legal history. It is a new wonder of the world. It is based upon falsehood in the main as to the facts—allegations of facts upon which it stands are not facts at all in many instances—and no decision made on any question—the first instance of a decision made under so many unfavorable circumstances—thus placed, has ever been held by the profession as law, and it has always needed confirmation before the lawyers regarded it as settled law. But Judge Douglas will have it that all hands must take this extraordinary decision, made under these extraordinary circumstances, and give their vote in Congress in accordance with it, yield to it and obey it in every possible sense. Circumstances alter cases. Do not gentlemen here remember the case of that same Supreme Court, some twenty-five or thirty years ago, deciding that a national bank was constitutional? I ask if somebody does not remember that a national bank was declared to be constitutional? Such is the truth, whether it be remembered or not. The bank charter ran out, and a recharter was granted by Congress. That recharter was laid before General Jackson.12 It was urged upon him, when he denied the constitutionality of the bank, that the Supreme Court had decided that it was constitutional; and General Jackson then said the Supreme Court had no right to lay down a rule to govern a coordinate branch of the government, the members of which had sworn to support the Constitution—that each member had sworn to support that Constitution as he understood it. I will venture here to say that I have heard Judge Douglas say that he approved of General Jackson for that act. What has now become of all his tirade against “resistance to the Supreme Court”?

My fellow citizens, getting back a little, for I pass from these points, when Judge Douglas makes his threat of annihilation upon the “alliance,” he is cautious to say that that warfare of his is to fall upon the leaders of the Republican party. Almost every word he utters, and every distinction he makes, has its significance. He means for the Republicans who do not count themselves as leaders to be his friends; he makes no fuss over them; it is the leaders that he is making war upon. He wants it understood that the mass of the Republican party are really his friends. It is only the leaders that are doing something, that are intolerant, and require extermination at his hands. As this is clearly and unquestionably the light in which he presents that matter, I want to ask your attention, addressing myself to Republicans here, that I may ask you some questions as to where you, as the Republican party, would be placed if you sustained Judge Douglas in his present position by a reelection? I do not claim, gentlemen, to be unselfish; I do not pretend that I would not like to go to the United States Senate; I make no such hypocritical pretense, but I do say to you that in this mighty issue, it is nothing to you—nothing to the mass of the people of the nation—whether or not Judge Douglas or myself shall ever be heard of after this night; it may be a trifle to either of us, but in connection with this mighty question, upon which hang the destinies of the nation, perhaps, it is absolutely nothing. But where will you be placed if you reindorse Judge Douglas? Don’t you know how apt he is—how exceedingly anxious he is at all times to seize upon anything and everything to persuade you that something he has done you did yourselves? Why, he tried to persuade you last night that our Illinois legislature instructed him to introduce the Nebraska bill. There was nobody in that legislature ever thought of such a thing; and when he first introduced the bill, he never thought of it; but still he fights furiously for the proposition, and that he did it because there was a standing instruction to our senators to be always introducing Nebraska bills. He tells you he is for the Cincinnati platform;13 he tells you he is for the Dred Scott decision. He tells you, not in his speech last night, but substantially in a former speech, that he cares not if slavery is voted up or down; he tells you the struggle on Lecompton is past—it may come up again or not, and if it does he stands where he stood when in spite of him and his opposition you built up the Republican party. If you endorse him, you tell him you do not care whether slavery be voted up or down, and he will close, or try to close, your mouths with his declaration repeated by the day, the week, the month, and the year. I think, in the position in which Judge Douglas stood in opposing the Lecompton Constitution, he was right; he does not know that it will return, but if it does we may know where to find him, and if it does not we may know where to look for him, and that is on the Cincinnati platform. Now I could ask the Republican party, after all the hard names Judge Douglas has called them by, all his repeated charges of their inclination to marry with and hug negroes, all his declarations of Black Republicanism—by the way, we are improving, the black has got rubbed off—but with all that, if he be endorsed by Republican votes, where do you stand? Plainly, you stand ready saddled, bridled, and harnessed, and waiting to be driven over to the slavery extension camp of the nation—just ready to be driven over, tied together in a lot—to be driven over, every man with a rope around his neck, that halter being held by Judge Douglas. That is the question. If Republican men have been in earnest in what they have done, I think they had better not do it; but I think the Republican party is made up of those who, as far as they can peaceably, will oppose the extension of slavery, and who will hope for its ultimate extinction. If they believe it is wrong in grasping up the new lands of the continent, and keeping them from the settlement of free white laborers, who want the land to bring up their families upon; if they are in earnest, although they may make a mistake, they will grow restless, and the time will come when they will come back again and reorganize, if not by the same name, at least upon the same principles as their party now has. It is better, then, to save the work while it is begun. You have done the labor; maintain it, keep it. If men choose to serve you, go with them; but as you have made up your organization upon principle, stand by it; for, as surely as God reigns over you, and has inspired your mind, and given you a sense of propriety, and continues to give you hope, so surely will you still cling to these ideas, and you will at last come back after your wanderings, merely to do your work over again.

We were often—more than once at least—in the course of Judge Douglas’ speech last night reminded that this government was made for white men—that he believed it was made for white men. Well, that is putting it into a shape in which no one wants to deny it; but the Judge then goes into his passion for drawing inferences that are not warranted. I protest, now and forever, against that counterfeit logic which presumes that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave, I do necessarily want her for a wife. My understanding is that I need not have her for either; but, as God made us separate, we can leave one another alone, and do one another much good thereby. There are white men enough to marry all the white women, and enough black men to marry all the black women, and in God’s name let them be so married. The Judge regales us with the terrible enormities that take place by the mixture of races; that the inferior race bears the superior down. Why, Judge, if we do not let them get together in the territories, they won’t mix there. (A voice: “Three cheers for Lincoln!” The cheers were given with a hearty good will.) I should say at least that that is a self-evident truth.

Now, it happens that we meet together once every year, somewhere about the Fourth of July, for some reason or other. These Fourth of July gatherings I suppose have their uses. If you will indulge me, I will state what I suppose to be some of them.

We are now a mighty nation: we are thirty, or about thirty, millions of people, and we own and inhabit about one fifteenth part of the dry land of the whole earth. We run our memory back over the pages of history for about eighty-two years, and we discover that we were then a very small people, in point of numbers vastly inferior to what we are now, with a vastly less extent of country, with vastly less of everything we deem desirable among men. We look upon the change as exceedingly advantageous to us and to our posterity, and we fix upon something that happened away back as in some way or other being connected with this rise of prosperity. We find a race of men living in that day whom we claim as our fathers and grandfathers; they were iron men; they fought for the principle that they were contending for; and we understood that by what they then did it has followed that the degree of prosperity which we now enjoy has come to us. We hold this annual celebration to remind ourselves of all the good done in this process of time, of how it was done and who did it, and how we are historically connected with it; and we go from these meetings in better humor with ourselves—we feel more attached the one to the other, and more firmly bound to the country we inhabit. In every way we are better men, in the age, and race, and country in which we live, for these celebrations. But after we have done all this, we have not yet reached the whole. There is something else connected with it. We have, besides these men—descended by blood from our ancestors—among us, perhaps half our people who are not descendants at all of these men; they are men who have come from Europe—German, Irish, French, and Scandinavian—men that have come from Europe themselves, or whose ancestors have come hither and settled here, finding themselves our equal in all things. If they look back through this history to trace their connection with those days by blood, they find they have none; they cannot carry themselves back into that glorious epoch and make themselves feel that they are part of us; but when they look through that old Declaration of Independence, they find that those old men say that “we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and then they feel that the moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh,14 of the men who wrote that Declaration, and so they are. That is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world.

Now, sirs, for the purpose of squaring things with this idea of “don’t care if slavery is voted up or voted down,” for sustaining the Dred Scott decision, for holding that the Declaration of Independence did not mean anything at all, we have Judge Douglas giving his exposition of what the Declaration of Independence means, and we have him saying that the people of America are equal to the people of England. According to his construction, you Germans are not connected with it. Now I ask you, in all soberness, if all these things, if indulged in, if ratified, if confirmed and endorsed, if taught to our children, and repeated to them, do not tend to rub out the sentiment of liberty in the country, and to transform this government into a government of some other form? Those arguments that are made, that the inferior race are to be treated with as much allowance as they are capable of enjoying; that as much is to be done for them as their condition will allow—what are these arguments? They are the arguments that kings have made for enslaving the people in all ages of the world. You will find that all the arguments in favor of kingcraft were of this class; they always bestrode the necks of the people—not that they wanted to do it, but because the people were better off for being ridden. That is their argument, and this argument of the Judge is the same old serpent that says, You work and I eat, you toil and I will enjoy the fruits of it. Turn in whatever way you will—whether it come from the mouth of a king, as an excuse for enslaving the people of his country, or from the mouth of men of one race as a reason for enslaving the men of another race, it is all the same old serpent, and I hold if that course of argumentation that is made for the purpose of convincing the public mind that we should not care about this should be granted, it does not stop with the negro. I should like to know—taking this old Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon principle, and making exceptions to it—where will it stop? If one man says it does not mean a negro, why not another say it does not mean some other man? If that Declaration is not the truth, let us get the statute-book in which we find it, and tear it out! Who is so bold as to do it? If it is not true, let us tear it out (cries of “No, no”). Let us stick to it, then; let us stand firmly by it, then.

It may be argued that there are certain conditions that make necessities and impose them upon us, and to the extent that a necessity is imposed upon a man, he must submit to it. I think that was the condition in which we found ourselves when we established this government. We had slaves among us; we could not get our Constitution unless we permitted them to remain in slavery; we could not secure the good we did secure if we grasped for more; but having by necessity submitted to that much, it does not destroy the principle that is the charter of our liberties. Let that charter stand as our standard.

My friend has said to me that I am a poor hand to quote Scripture. I will try it again, however. It is said in one of the admonitions of our Lord, “Be ye [therefore] perfect even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect.”15 The Savior, I suppose, did not expect that any human creature could be perfect as the Father in heaven; but he said, “As your Father in heaven is perfect, be ye also perfect.” He set that up as a standard, and he who did most toward reaching that standard attained the highest degree of moral perfection. So I say in relation to the principle that all men are created equal, let it be as nearly reached as we can. If we cannot give freedom to every creature, let us do nothing that will impose slavery upon any other creature. Let us then turn this government back into the channel in which the framers of the Constitution originally placed it. Let us stand firmly by each other. If we do not do so, we are tending in the contrary direction that our friend Judge Douglas proposes—not intentionally—working in the traces that tend to make this one universal slave nation. He is one that runs in that direction, and as such I resist him.

My friends, I have detained you about as long as I desired to do, and I have only to say, let us discard all this quibbling about this man and the other man, this race and that race and the other race being inferior, and therefore they must be placed in an inferior position. Let us discard all these things, and unite as one people throughout this land, until we shall once more stand up declaring that all men are created equal.

My friends, I could not, without launching off upon some new topic, which would detain you too long, continue tonight. I thank you for this most extensive audience that you have furnished me tonight. I leave you, hoping that the lamp of liberty will burn in your bosoms until there shall no longer be a doubt that all men are created free and equal.

- 1. Douglas referred to the antirepublican “Holy Alliance” of Prussia, Austria, and Russia that formed in the aftermath of the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. A remnant of the alliance (Russia and Austria) fought the Crimean War (1853–1856) against Great Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire. The battle of Sebastopol, which Douglas referred to a few lines below, took place during that war.

- 2. James Buchanan (1791–1868), a Democrat, was elected president in 1856.

- 3. Lincoln referred to Douglas as “Judge Douglas” because he had been an associate justice on the Illinois Supreme Court from 1841 to 1843.

- 4. The Dred Scott decision.

- 5. John C. Calhoun (1782–1850) was a vice president, secretary of state, secretary of war, a representative from South Carolina, and a long-serving senator from that state. He was perhaps the leading proslavery politician in antebellum America.

- 6. Lyman Trumbull (1813–1896) began his political career as a Democrat but became a Republican. He was elected senator from Illinois in 1855. While in the Senate, as chairman of the Judiciary Committee, he coauthored the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery.

- 7. The House Divided Speech.

- 8. Matthew 12:25.

- 9. The Whigs were one of the two great antebellum parties. The Democrats were the other.

- 10. Orville H. Browning (1806–1881) was a lawyer and Republican politician in Illinois.

- 11. For example, The Dred Scott decision.

- 12. President Andrew Jackson (1767–1845).

- 13. The Cincinnati platform was the statement of the Democratic party’s goals adopted at the 1856 Democratic Convention, the convention that nominated James Buchanan.

- 14. Leviticus 17:11; Matthew 16:17; John 6:53.

- 15. Matthew 5:48.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.