No related resources

Introduction

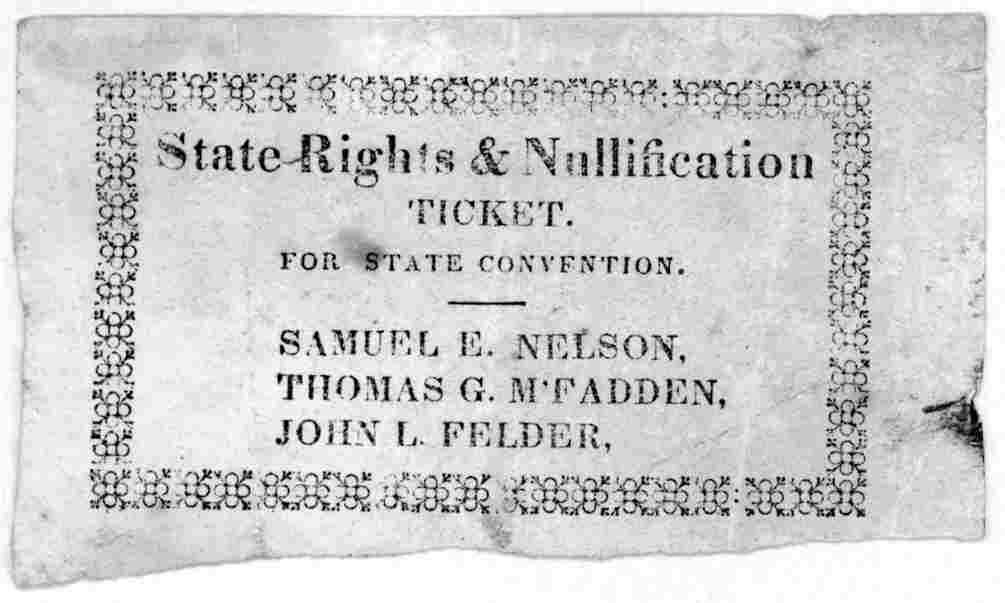

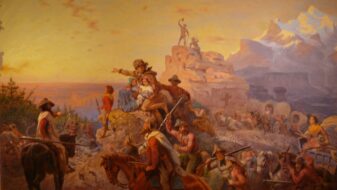

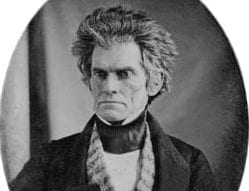

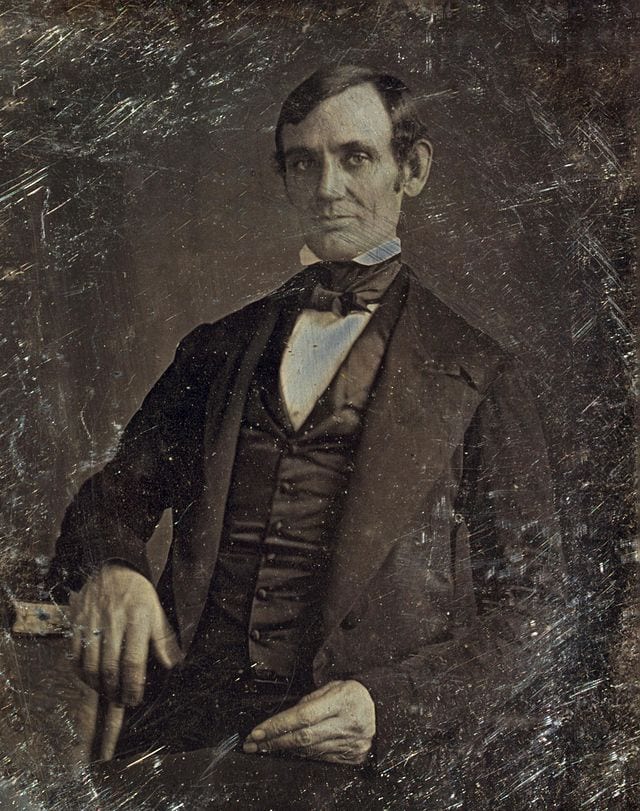

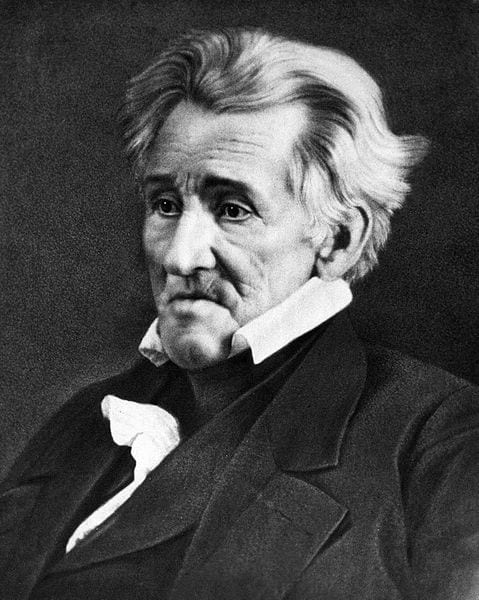

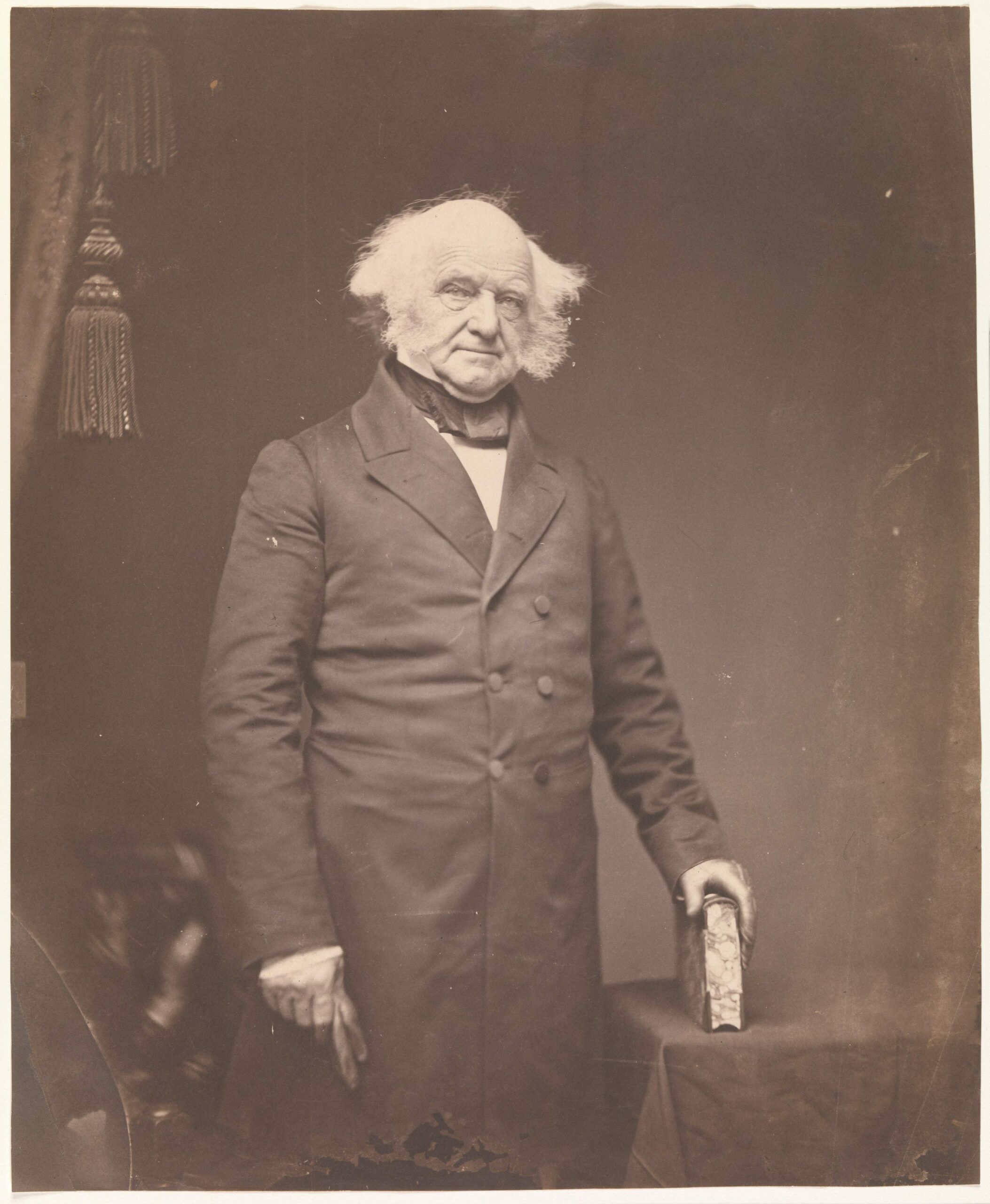

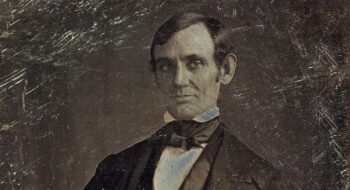

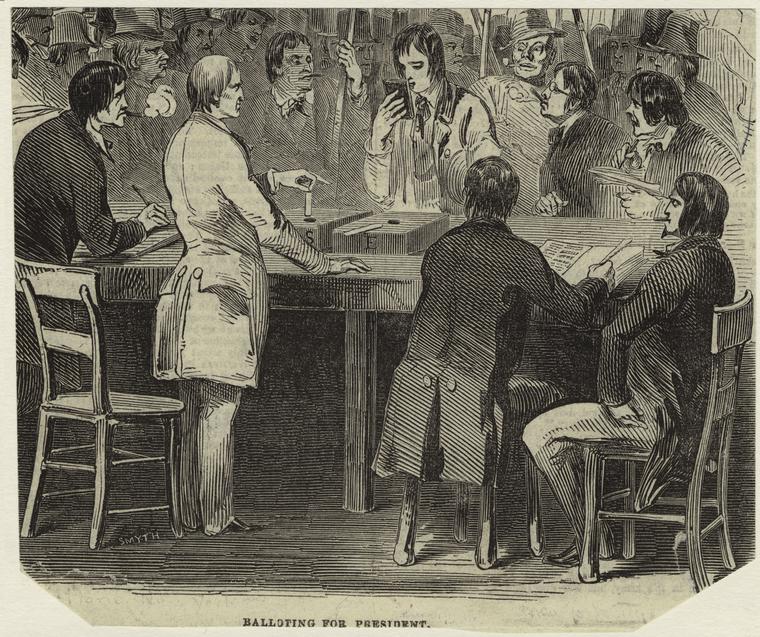

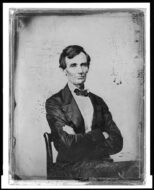

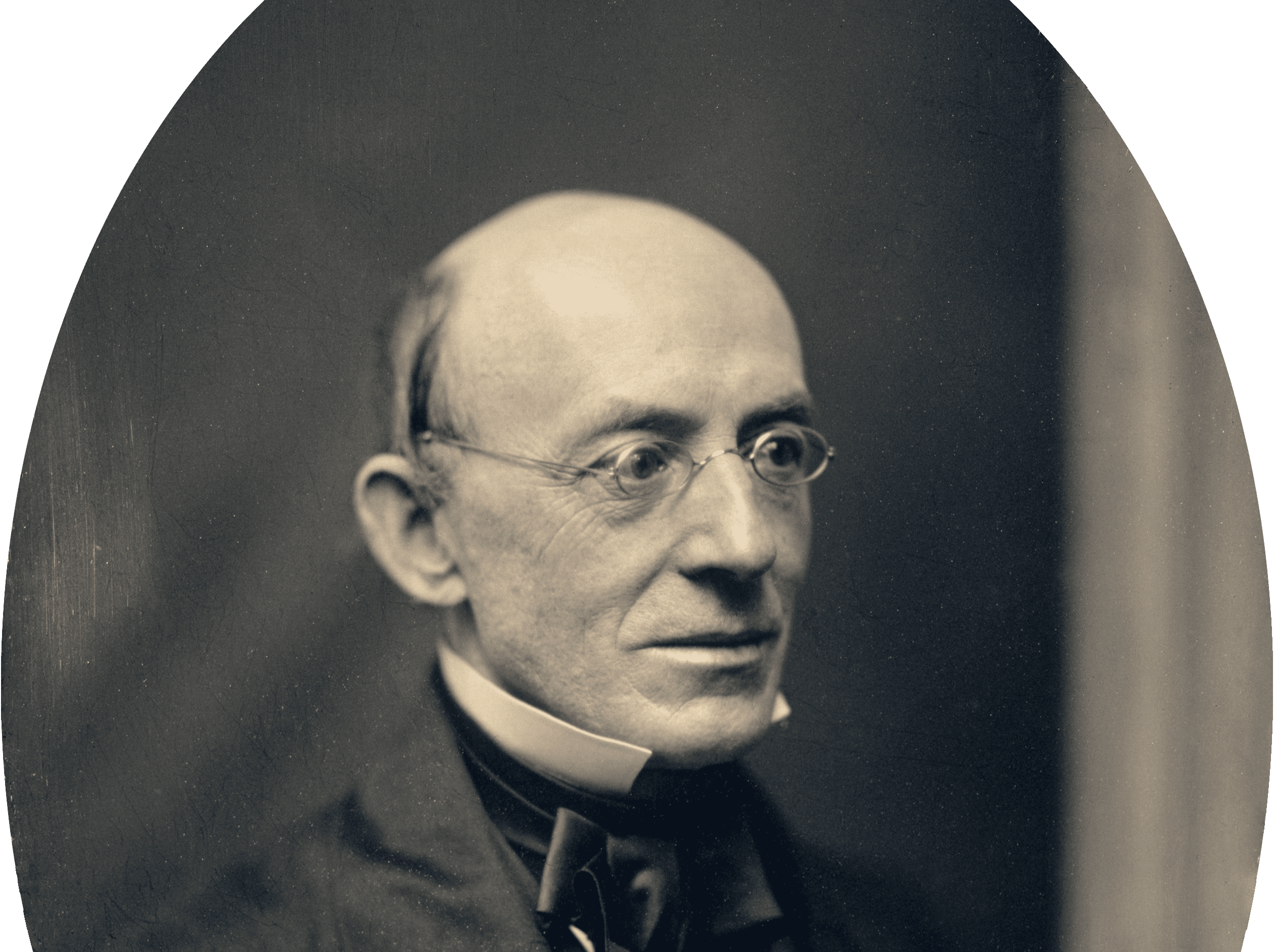

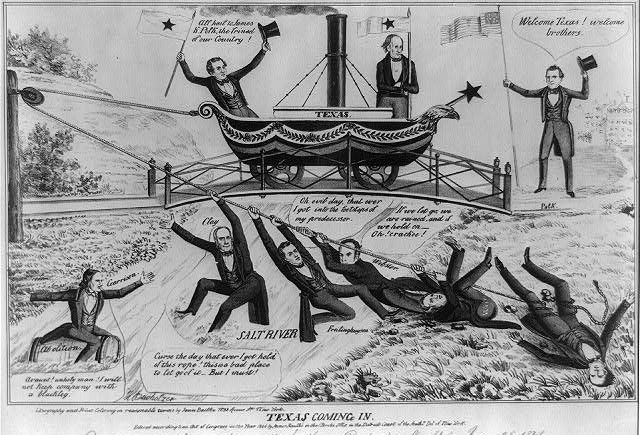

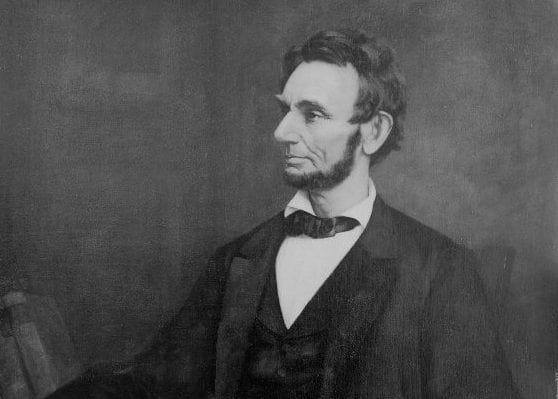

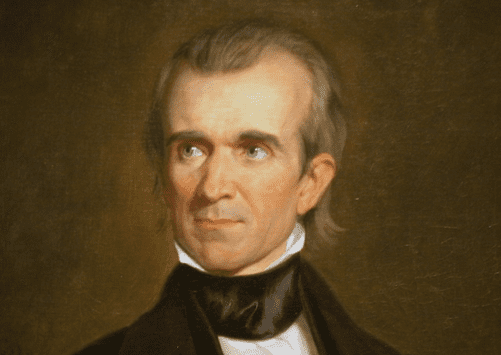

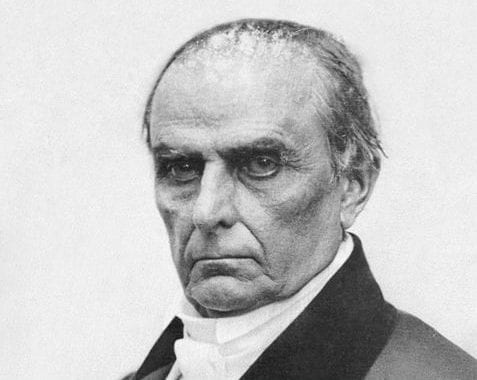

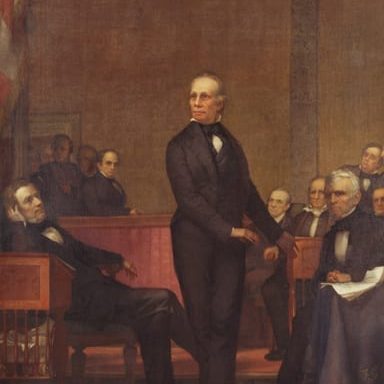

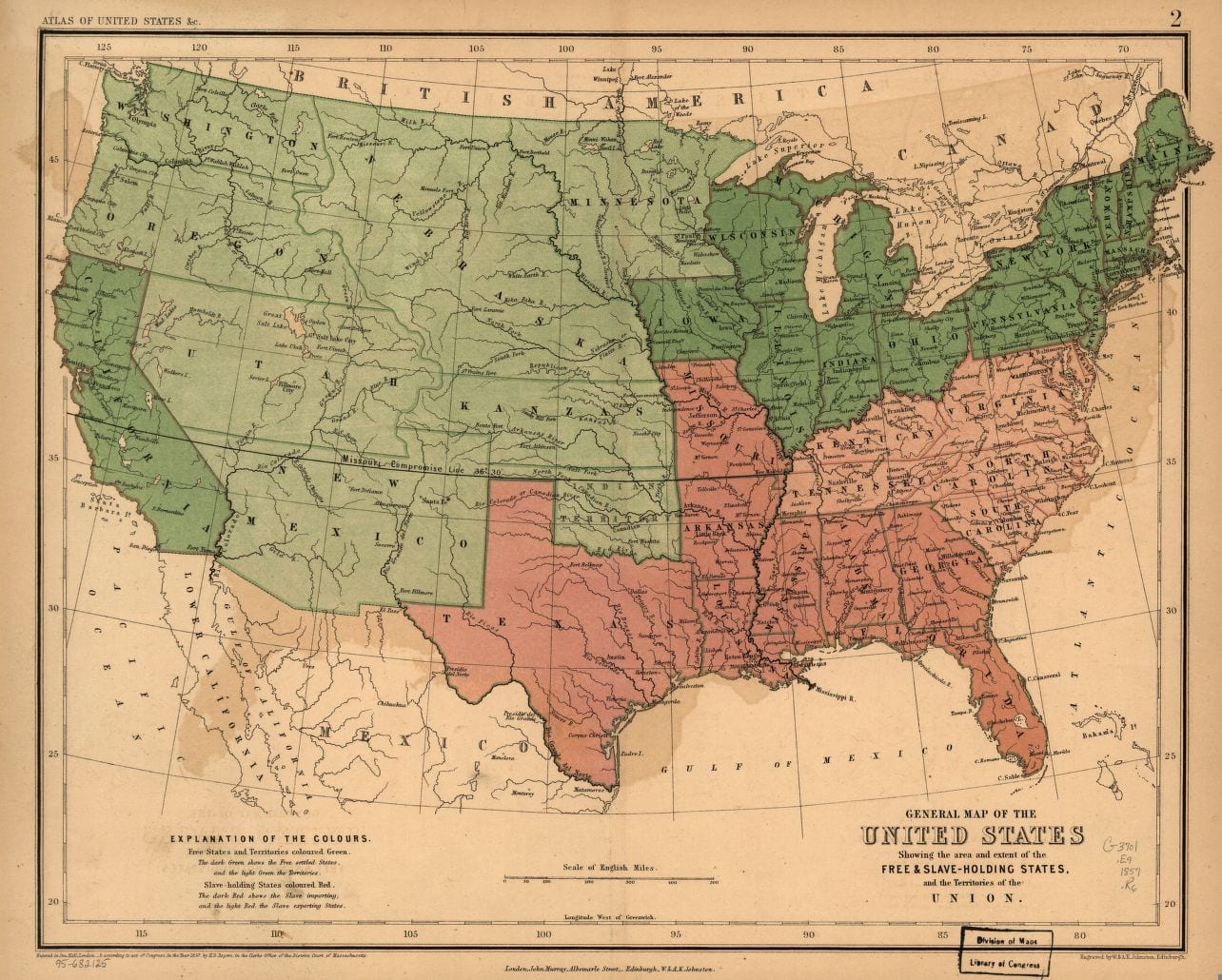

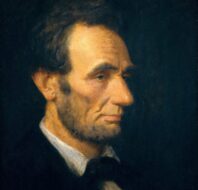

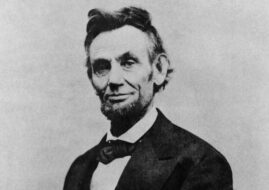

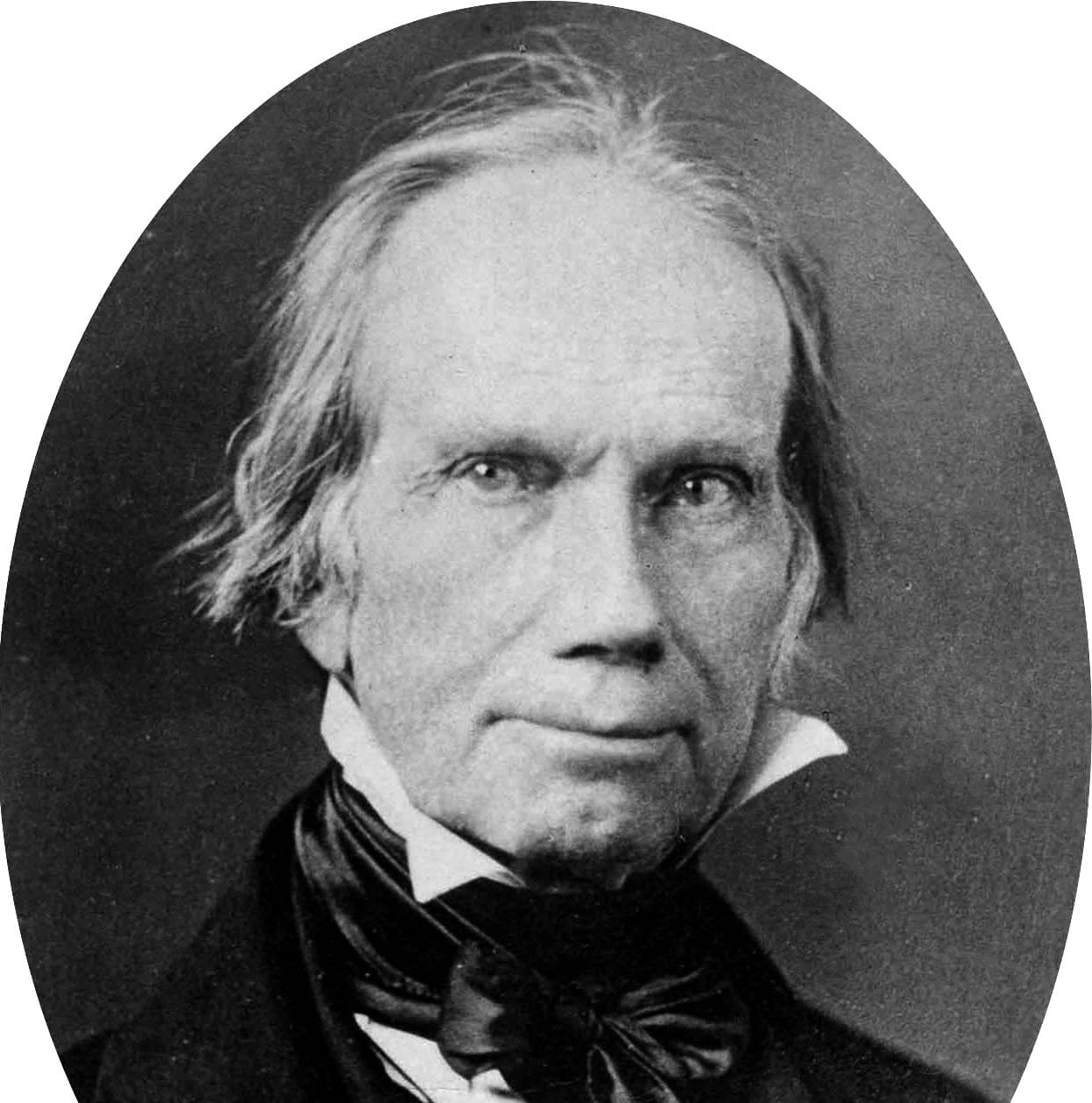

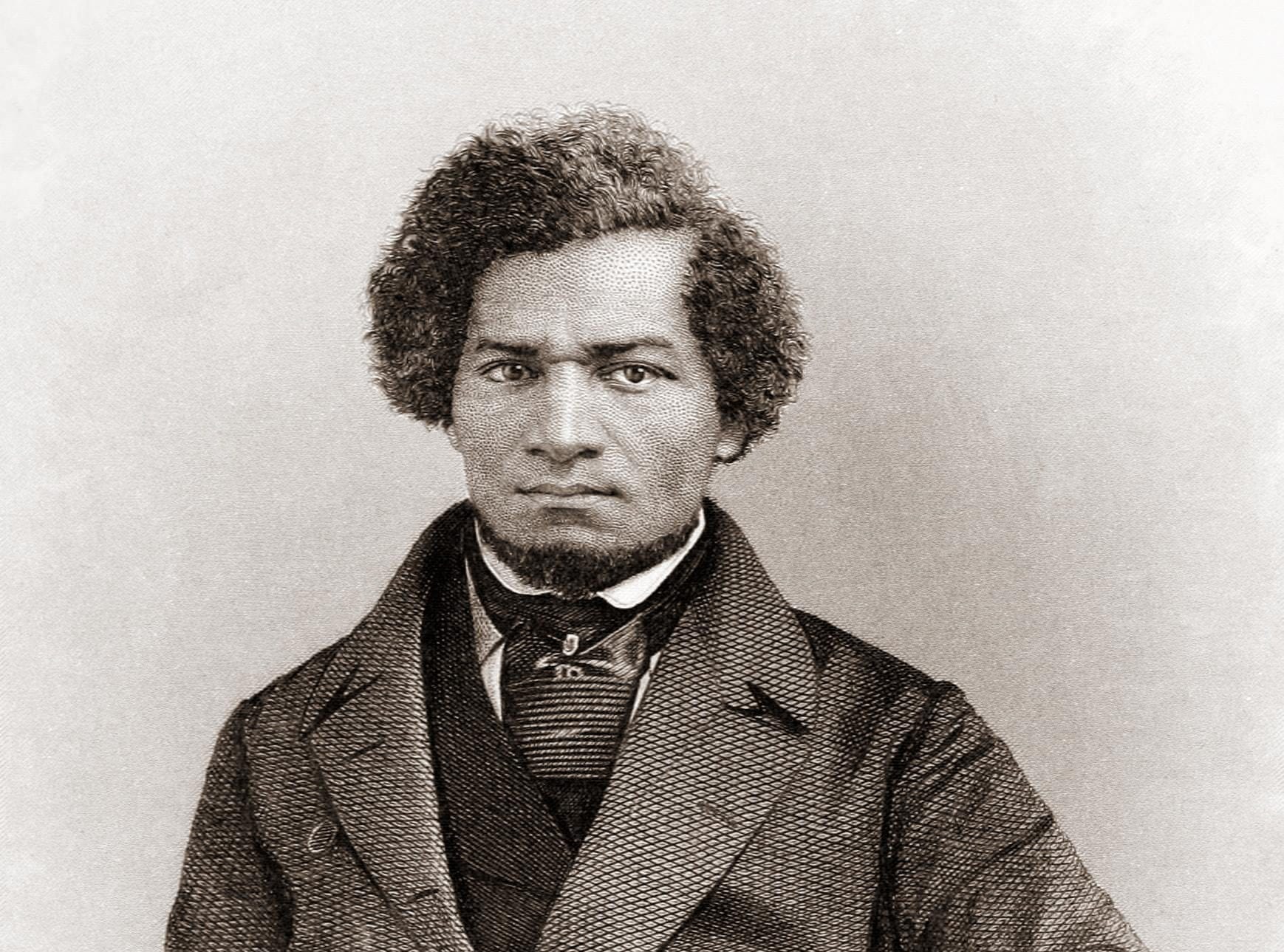

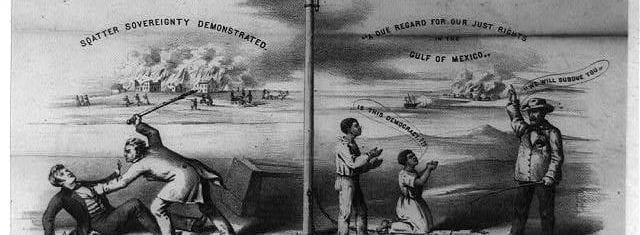

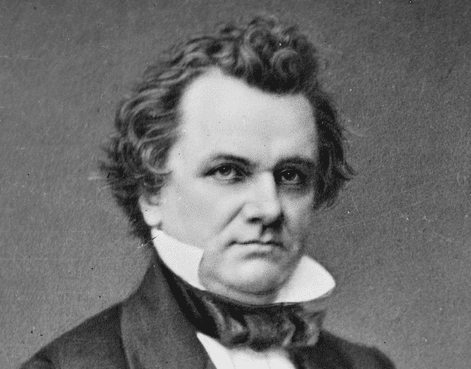

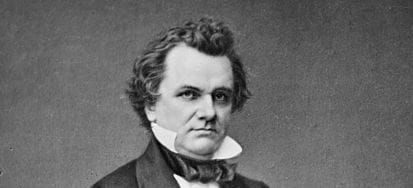

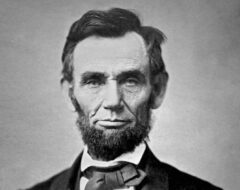

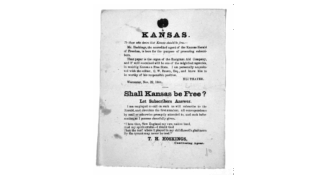

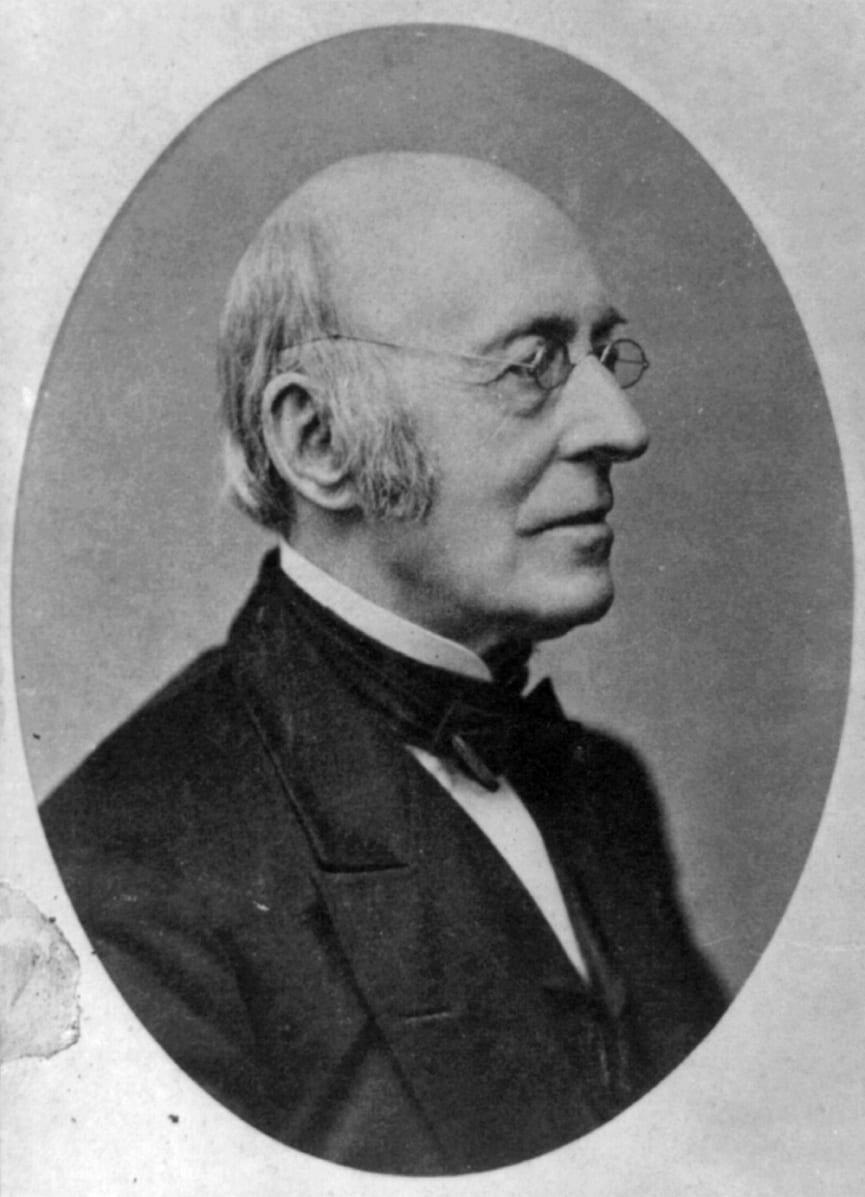

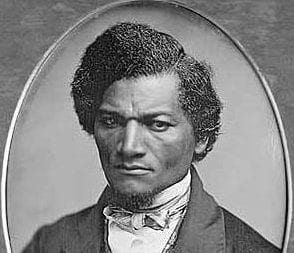

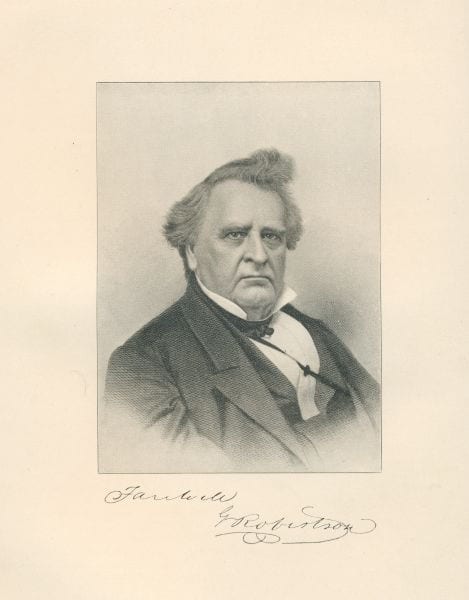

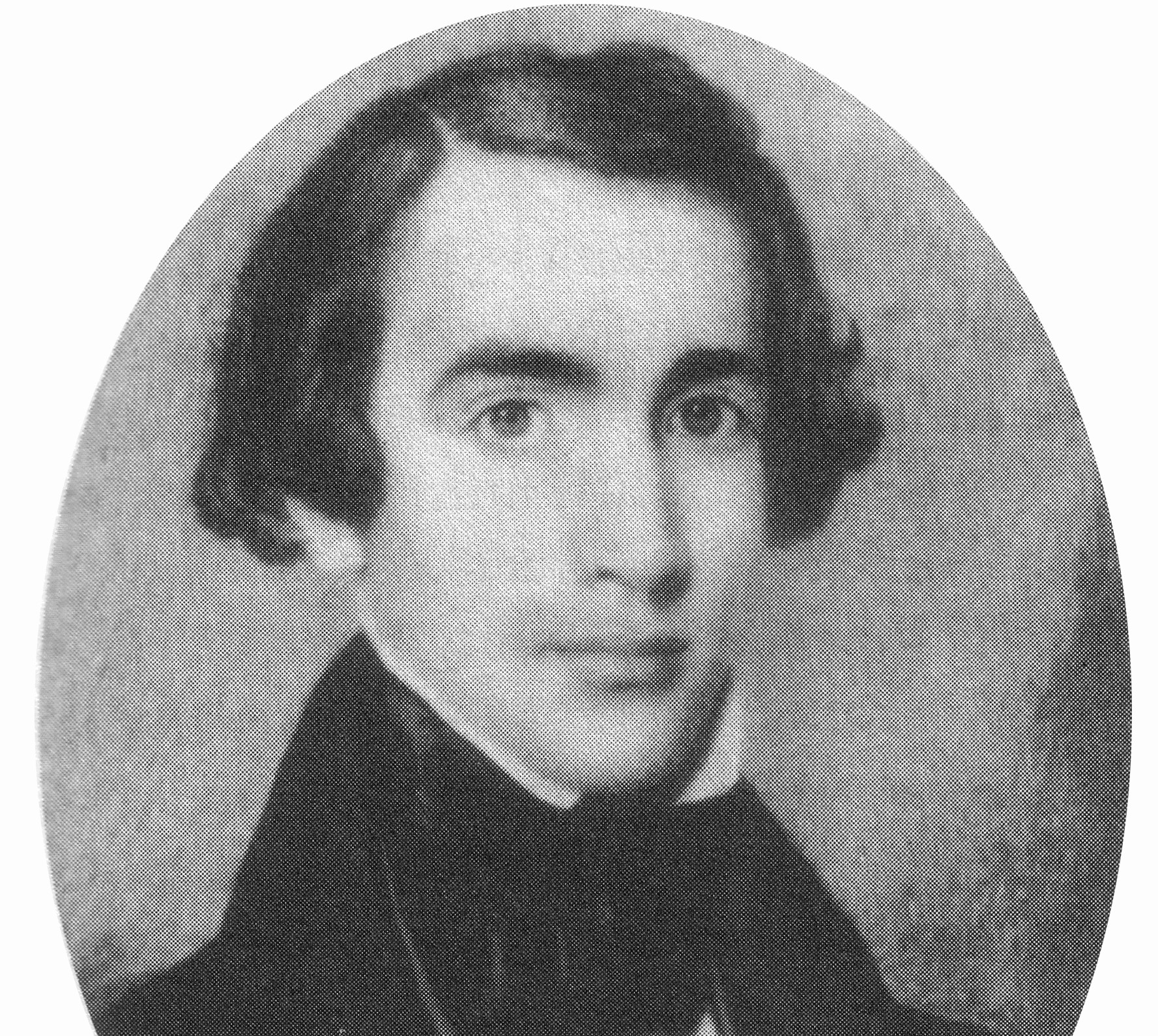

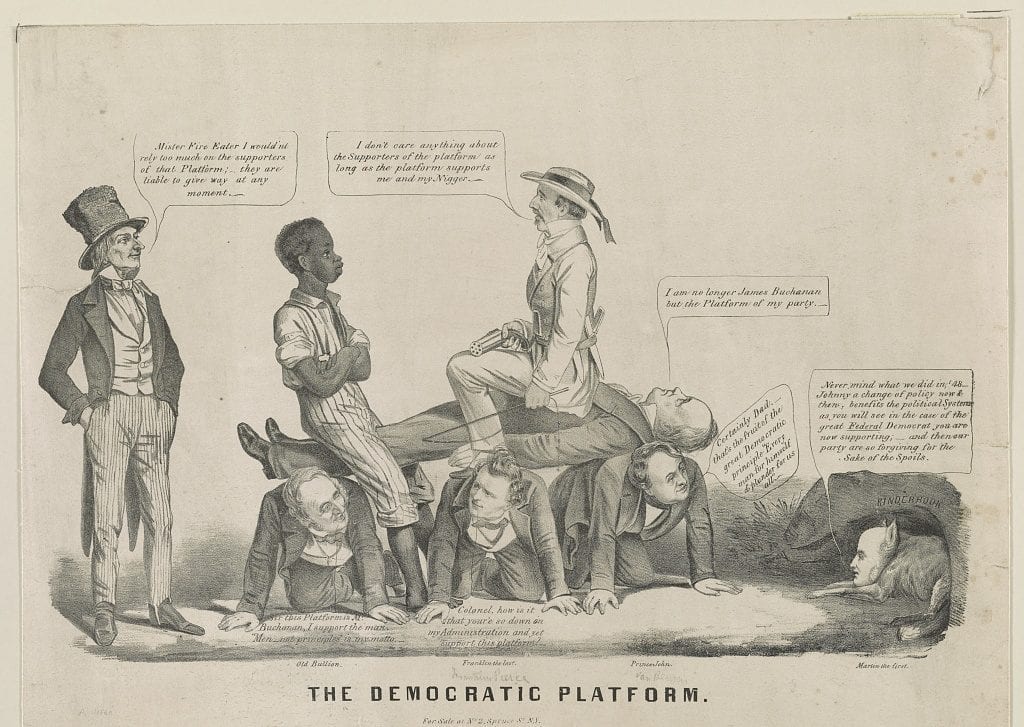

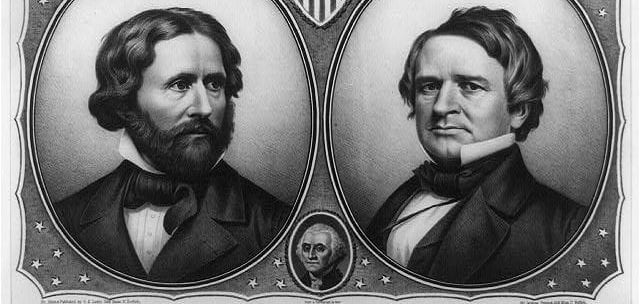

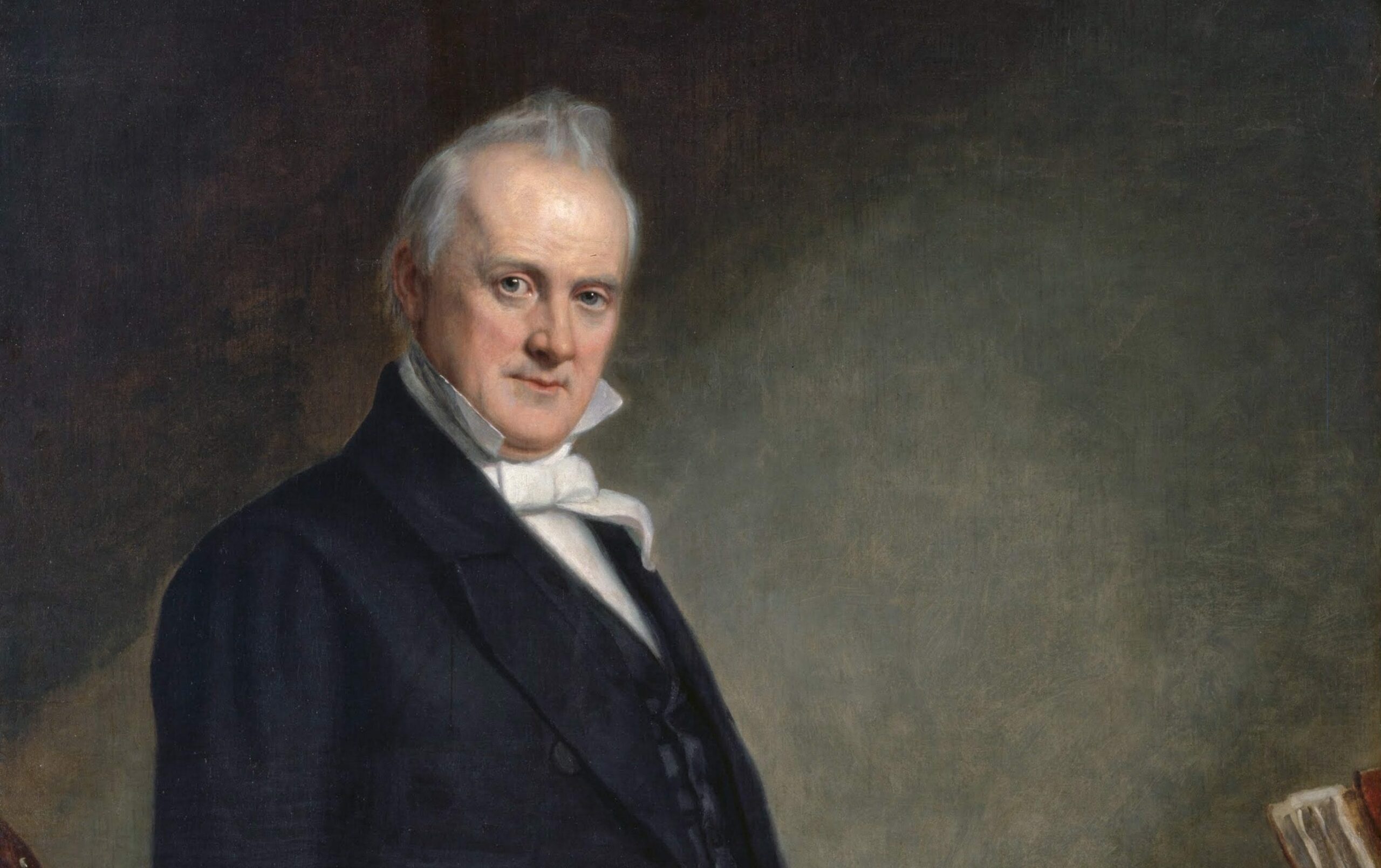

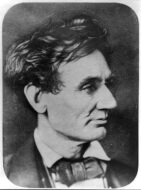

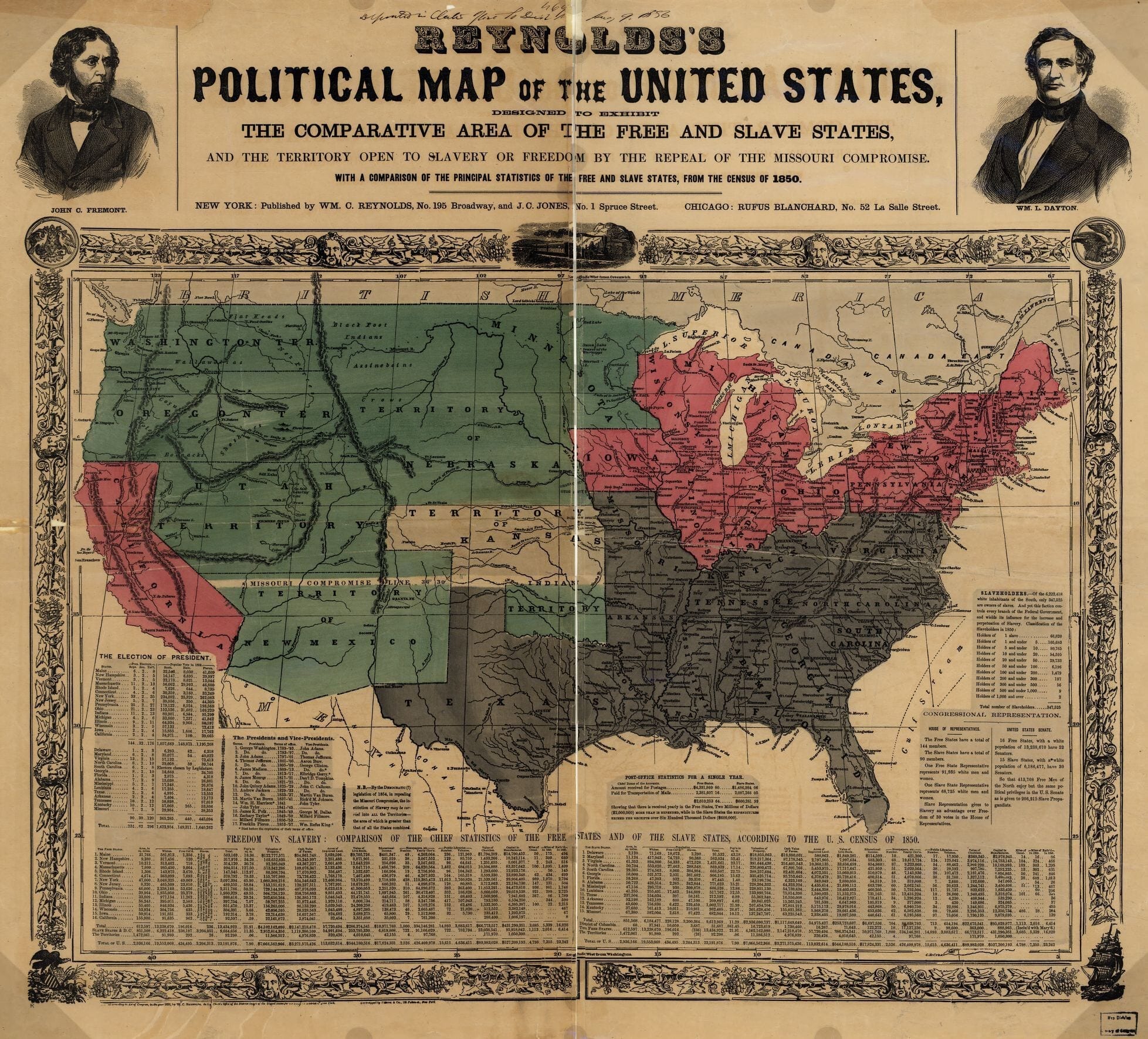

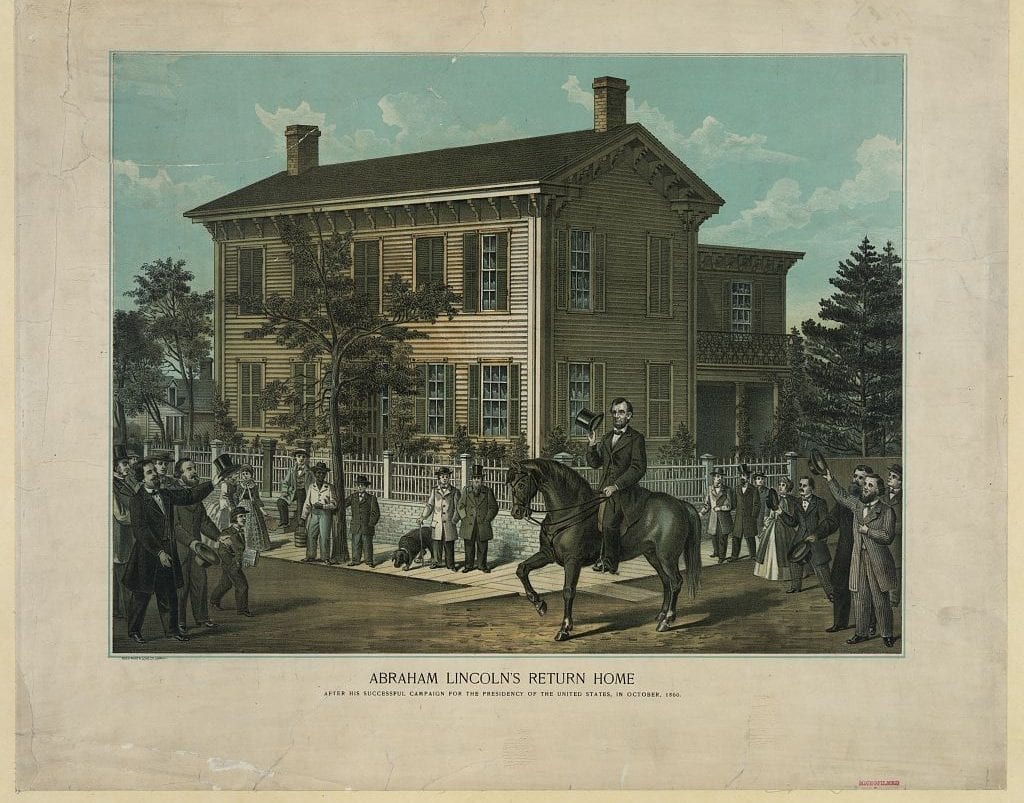

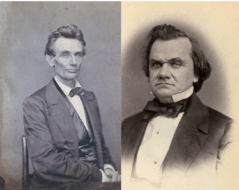

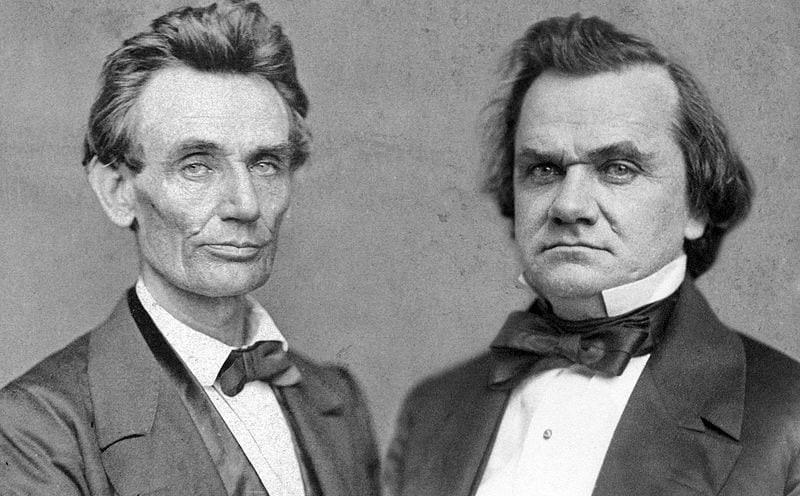

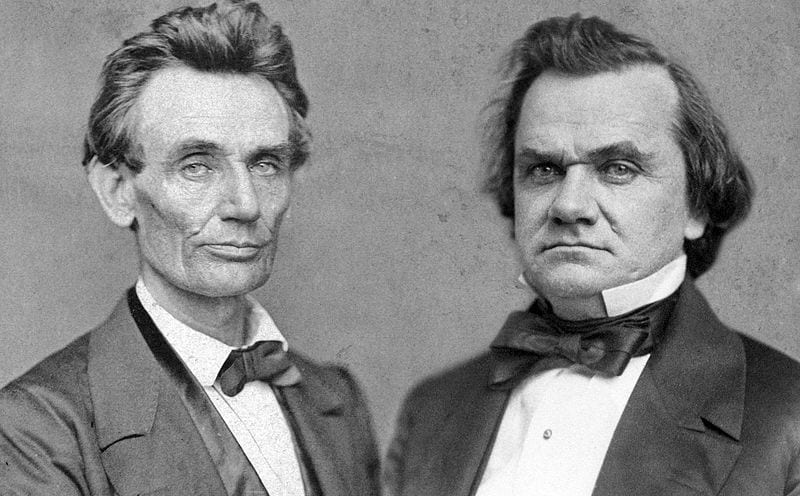

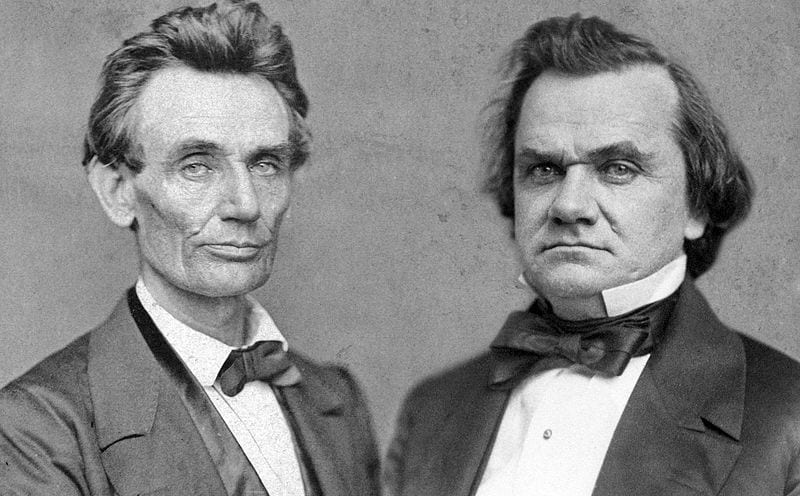

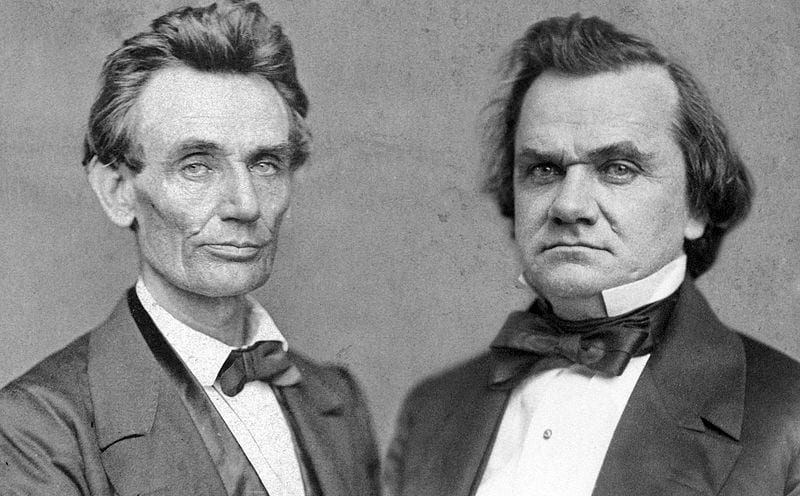

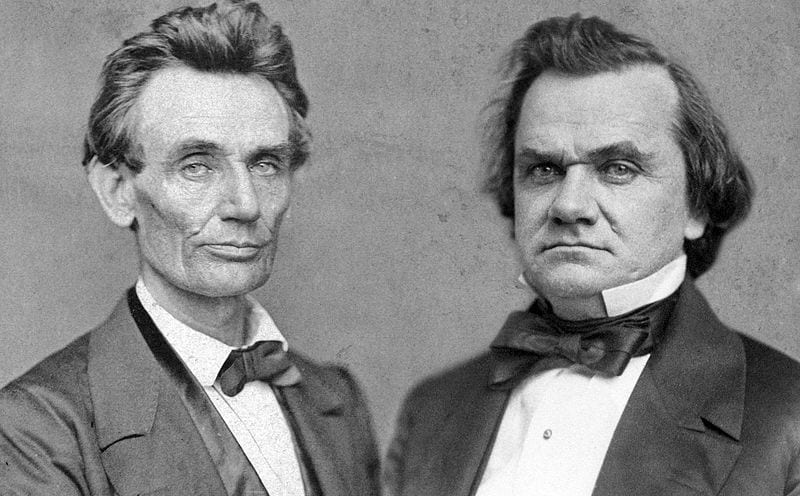

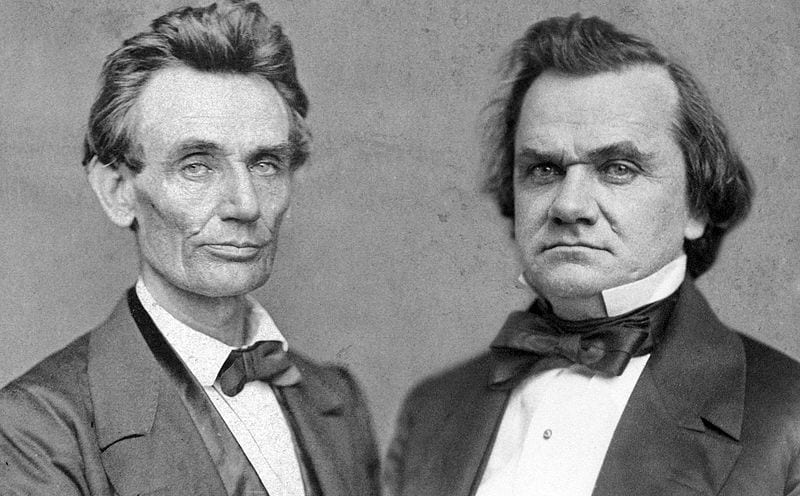

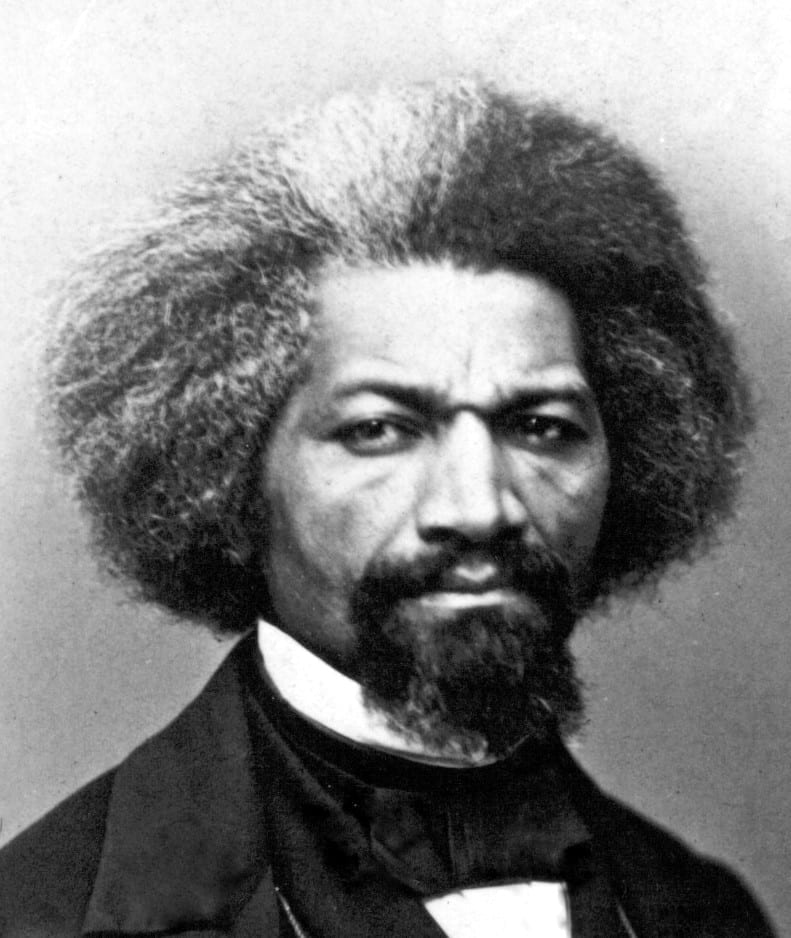

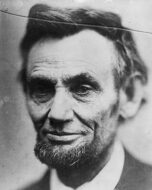

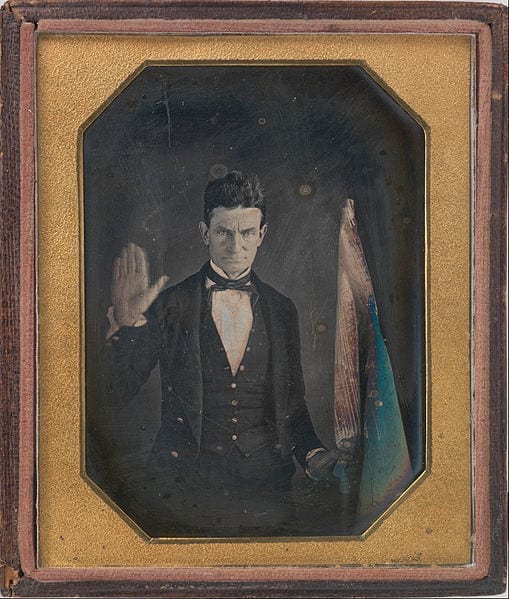

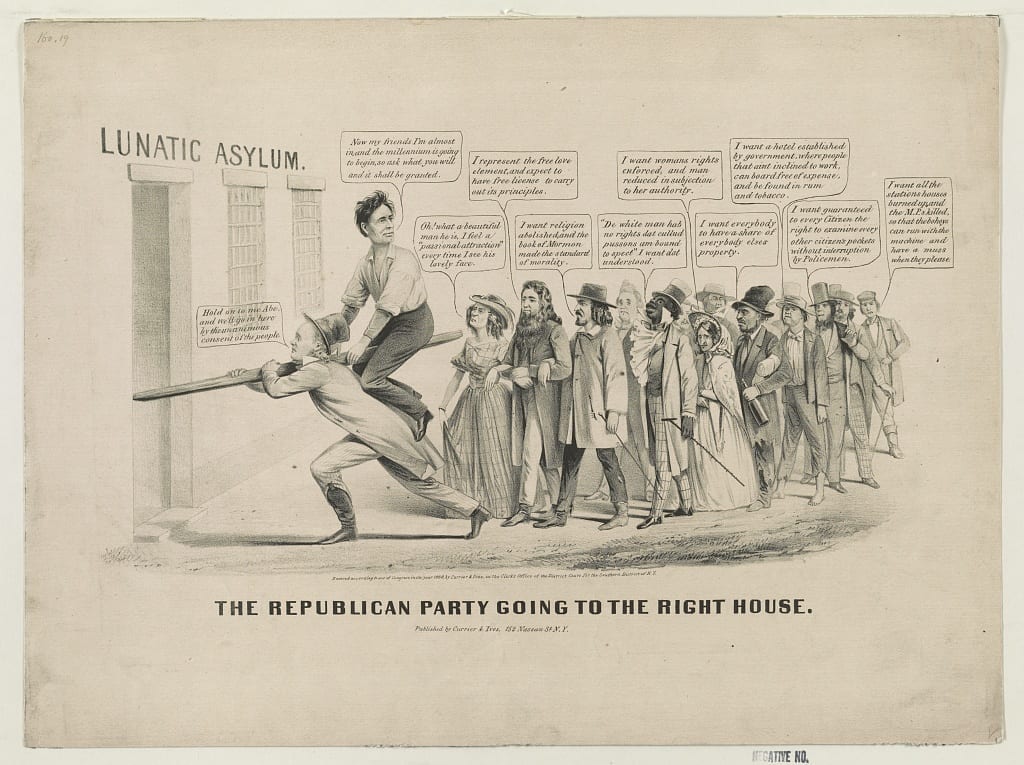

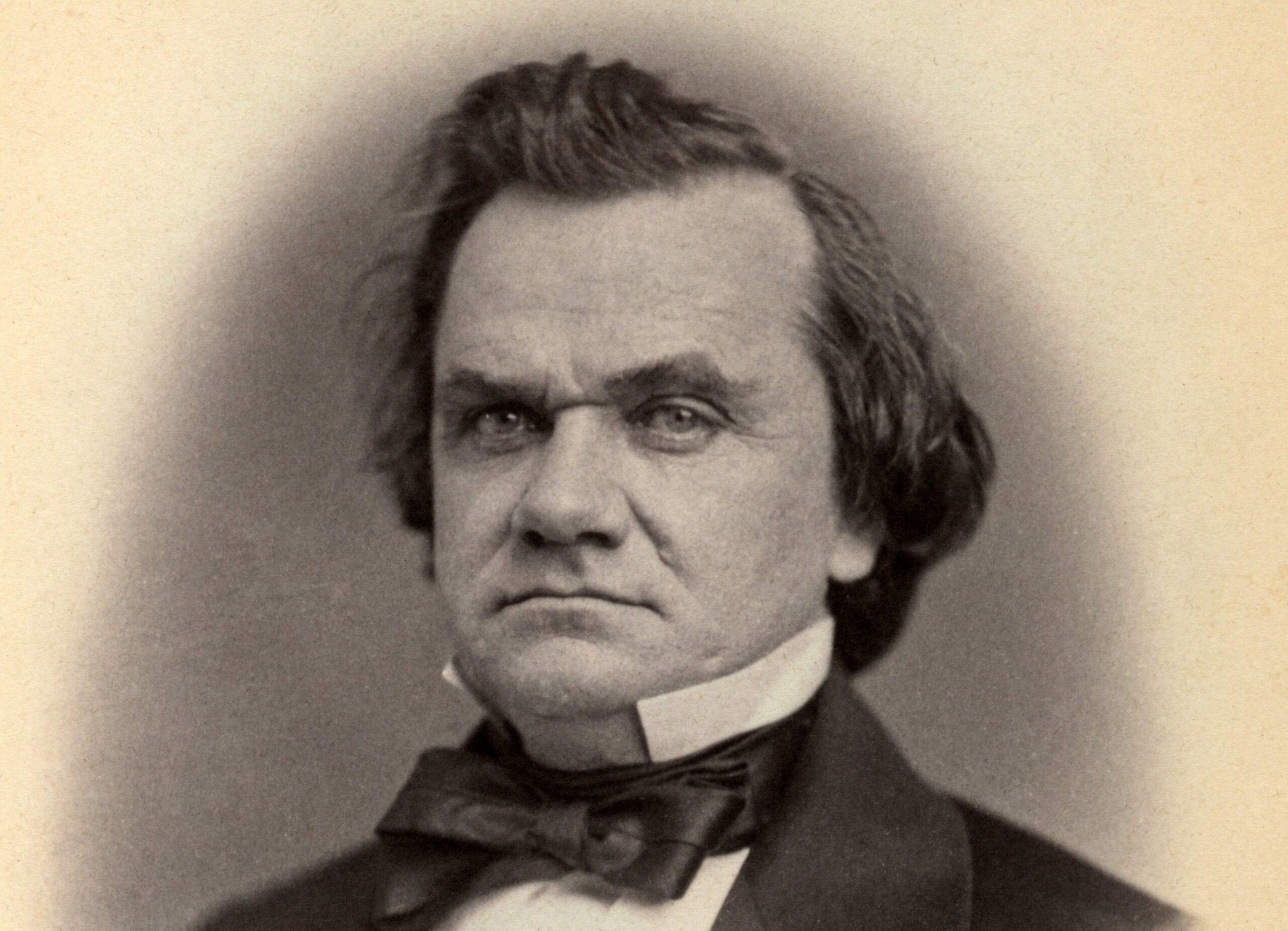

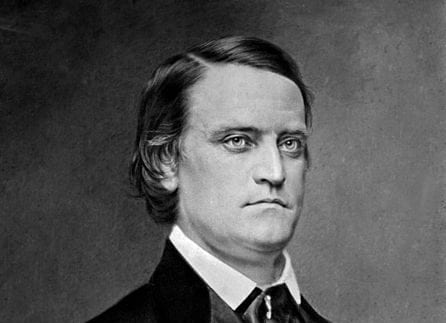

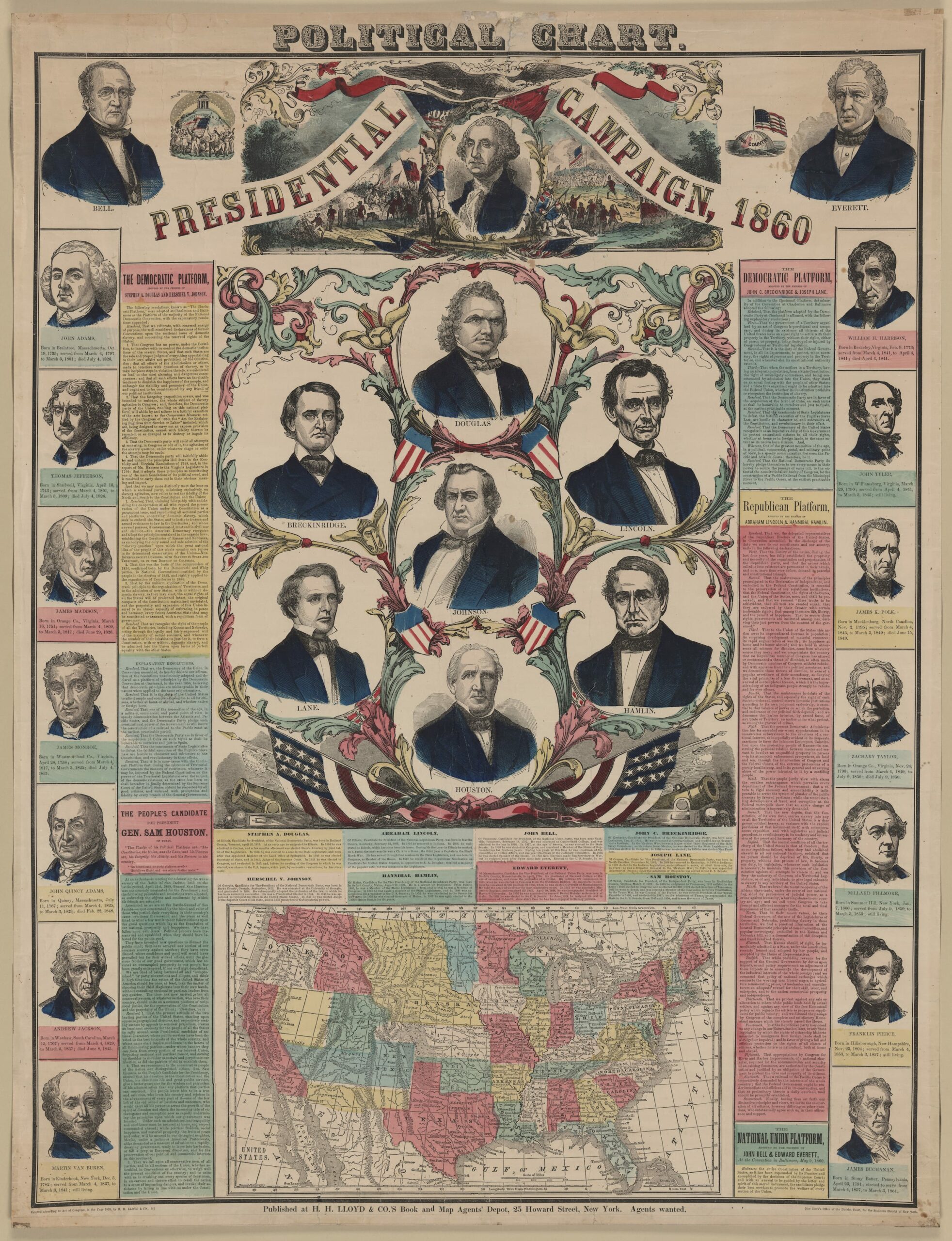

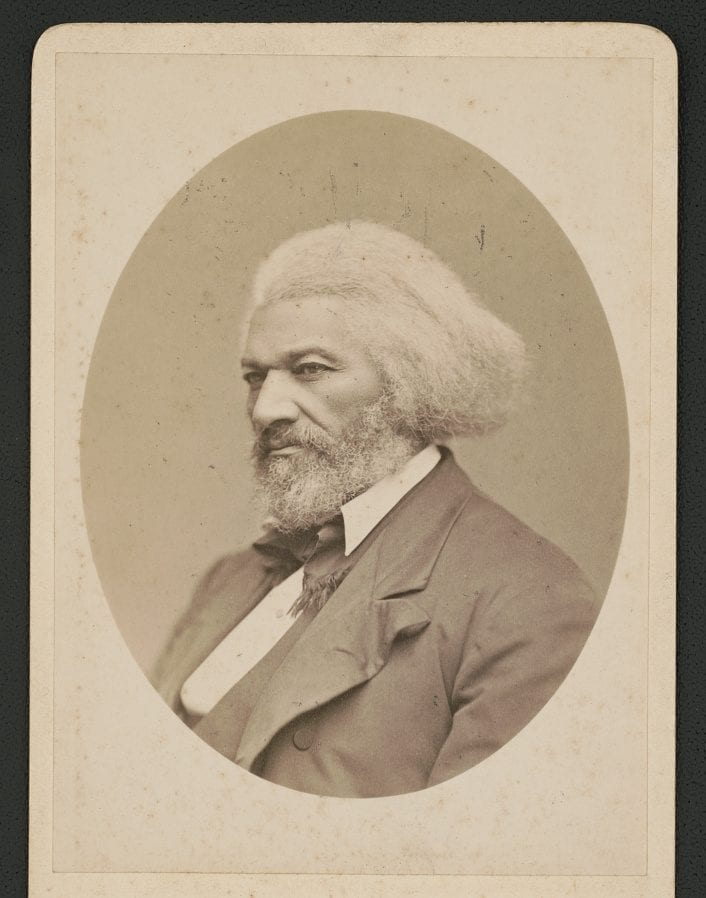

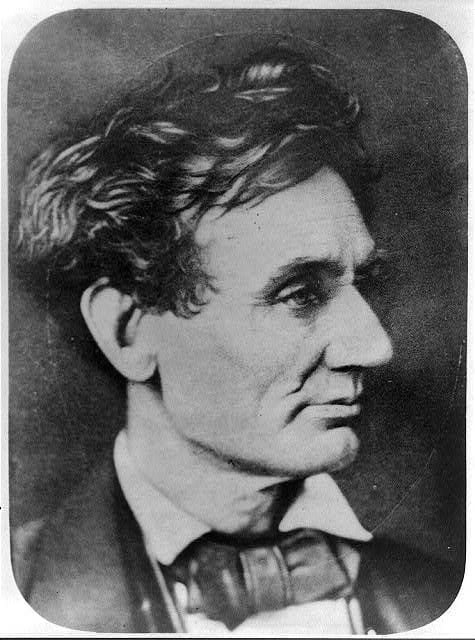

This address at Peoria, Illinois on the subject of the repeal of the Missouri Compromise represented the return of Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) to politics after a short-lived retirement. Following his single two-year term in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1847–1849, Lincoln returned to his law practice and settled down, leaving public service behind. But the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which allowed the people of the territories to decide for themselves whether they wanted slavery or not, roused Lincoln like nothing had before. The author of the law, Illinois’ Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas (1813–1861), insisted on the principle of popular sovereignty, the claim that the people of a territory, through their ballots, and not Congress, had a right to choose whether the territory would be free or slave. This meant the end of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had affirmed Congress’s right to prohibit the extension of slavery into the territories north of the 36°30′ parallel.

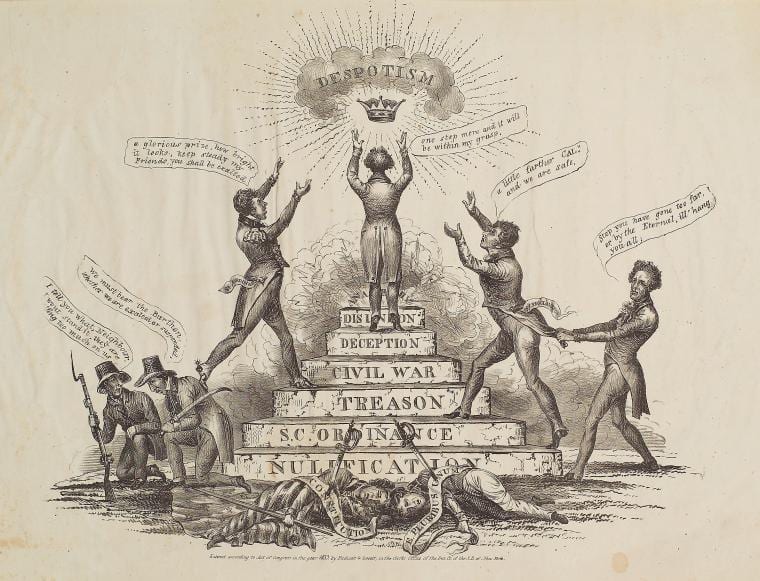

Lincoln’s speech brought together with vigor and clarity the historical, political, and practical arguments against the expansion of slavery into the territories made in support of the Missouri Compromise since its passage in 1820. In responding to Douglas’s argument about popular sovereignty, however, Lincoln went beyond historical and constitutional issues to something more important. He examined the fundamental issue of American democracy. The Missouri Compromise represented an extension of the compromises with slavery in the Constitution (See The Three-Fifths Clause, The Slave Trade Clause, and The Fugitive Slave Clause). It was reached on the basis that the existence of slavery was a fact, and thus dealing with it a necessity (see Speech to Congress). If the vote of the people, the sovereign political authority, could approve the existence of slavery where it had not been before, it would give property in men the appearance of a right, sanctioned by the moral right of the people to rule themselves. If slavery could be made to appear right by the vote of the people, what limit was there to the evil the people could do with their sovereign power? The repeal of the Missouri Compromise meant, according to Lincoln, the repeal of all moral restraint on the popular will. For that reason, Lincoln opposed repeal. He argued that there is only one thing more powerful than the people, only one thing to which they must bow, the principles of eternal right.

We have excerpted and placed in Appendix D the historical argument that Lincoln made against the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, since this history provides useful background for many of the documents in this collection. The excerpt below excludes many of the practical and political arguments in Lincoln’s speech to focus on his moral argument.

Source: Life and Works of Abraham Lincoln, Centenary Edition, Volume II, Marion Mills Miller, ed., (New York: The Current Literature Publishing Company, 1907), 218–275, https:// archive.org/details/lifeworks02lincuoft/page/274.

The repeal of the Missouri Compromise, and the propriety of its restoration, constitute the subject of what I am about to say. . . .

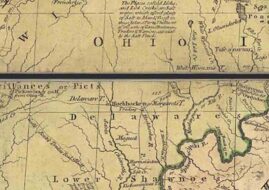

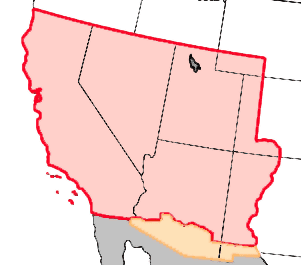

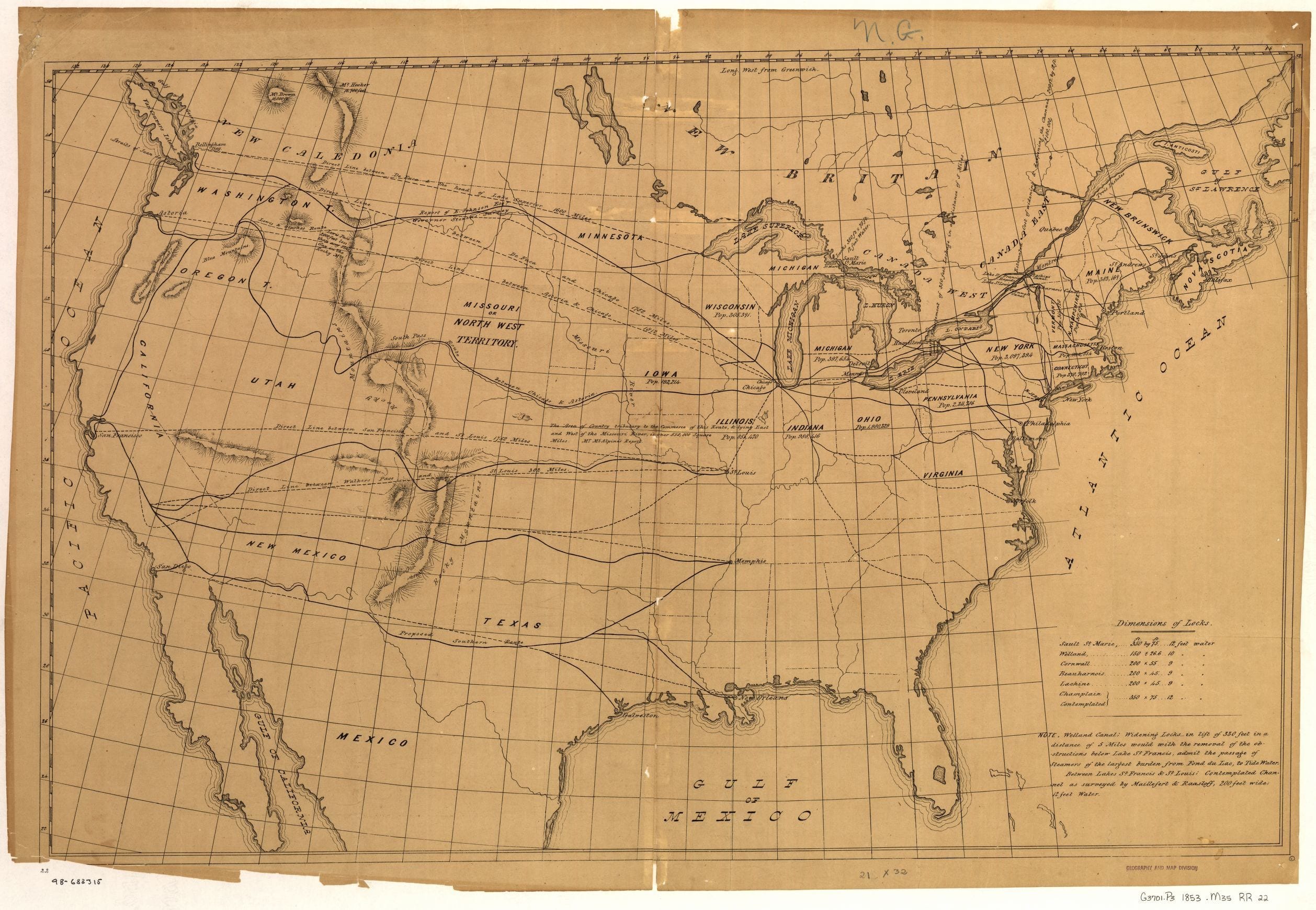

I now come to consider whether the repeal, with its avowed principle, is intrinsically right. I insist that it is not. Take the particular case. A controversy had arisen between the advocates and opponents of slavery, in relation to its establishment within the country we had purchased of France.[1] The southern, and then best part of the purchase, was already in as a slave state. The controversy was settled by also letting Missouri in as a slave state; but with the agreement that within all the remaining part of the purchase, north of a certain line, there should never be slavery. As to what was to be done with the remaining part south of the line, nothing was said; but perhaps the fair implication was, that it should come in with slavery if it should so choose. The southern part, except a portion heretofore mentioned, afterwards did come in with slavery, as the state of Arkansas. All these many years since 1820, the northern part had remained a wilderness. At length settlements began in it also. In due course, Iowa, came in as a free state, and Minnesota was given a territorial government, without removing the slavery restriction. Finally, the sole remaining part, north of the line, Kansas and Nebraska, was to be organized; and it is proposed, and carried, to blot out the old dividing line of thirty-four years standing, and to open the whole of that country to the introduction of slavery. Now, this, to my mind, is manifestly unjust. After an angry and dangerous controversy, the parties made friends by dividing the bone of contention. The one party first appropriates her own share, beyond all power to be disturbed in the possession of it; and then seizes the share of the other party. It is as if two starving men had divided their only loaf; the one had hastily swallowed his half, and then grabbed the other half just as he was putting it to his mouth. . . .

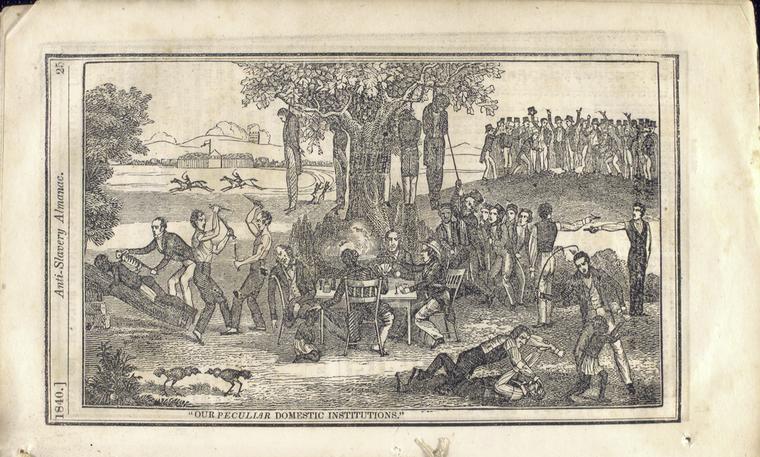

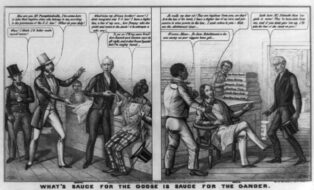

Equal justice to the South, it is said, requires us to consent to the extending of slavery to new countries. That is to say, inasmuch as you do not object to my taking my hog to Nebraska, therefore I must not object to you taking your slave. Now, I admit this is perfectly logical, if there is no difference between hogs and Negroes. But while you thus require me to deny the humanity of the Negro, I wish to ask whether you of the South yourselves, have ever been willing to do as much? It is kindly provided that of all those who come into the world, only a small percentage are natural tyrants. That percentage is no larger in the slave states than in the free. The great majority, South as well as North, have human sympathies, of which they can no more divest themselves than they can of their sensibility to physical pain. These sympathies in the bosoms of the Southern people, manifest in many ways, their sense of the wrong of slavery, and their consciousness that, after all, there is humanity in the Negro. If they deny this, let me address them a few plain questions. In 1820 you joined the North, almost unanimously, in declaring the African slave trade piracy, and in annexing to it the punishment of death.[2] Why did you do this? If you did not feel that it was wrong, why did you join in providing that men should be hung for it? The practice was no more than bringing wild Negroes from Africa, to sell to such as would buy them. But you never thought of hanging men for catching and selling wild horses, wild buffaloes or wild bears.

Again, you have amongst you, a sneaking individual, of the class of native tyrants, known as the “slave dealer.” He watches your necessities, and crawls up to buy your slave, at a speculating price. If you cannot help it, you sell to him; but if you can help it, you drive him from your door. You despise him utterly. You do not recognize him as a friend, or even as an honest man. Your children must not play with his; they may rollick freely with the little Negroes, but not with the “slave dealer’s” children. If you are obliged to deal with him, you try to get through the job without so much as touching him.

It is common with you to join hands with the men you meet; but with the slave dealer you avoid the ceremony—instinctively shrinking from the snaky contact. If he grows rich and retires from business, you still remember him, and still keep up the ban of non-intercourse upon him and his family. Now why is this? You do not so treat the man who deals in corn, cattle or tobacco. And yet again; there are in the United States and territories, including the District of Columbia, 433,643 free blacks. At $500 per head they are worth over two hundred millions of dollars. How comes this vast amount of property to be running about without owners? We do not see free horses or free cattle running at large. How is this? All these free blacks are the descendants of slaves, or have been slaves themselves, and they would be slaves now, but for something which has operated on their white owners, inducing them, at vast pecuniary sacrifices, to liberate them. What is that something? Is there any mistaking it? In all these cases it is your sense of justice, and human sympathy, continually telling you, that the poor Negro has some natural right to himself—that those who deny it, and make mere merchandise of him, deserve kickings, contempt and death.

And now, why will you ask us to deny the humanity of the slave and estimate him only as the equal of the hog? Why ask us to do what you will not do yourselves? Why ask us to do for nothing, what two hundred million dollars could not induce you to do?

But one great argument in the support of the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, is still to come. That argument is “the sacred right of self-government.” It seems our distinguished senator[3] has found great difficulty in getting his antagonists, even in the Senate to meet him fairly on this argument. Some poet has said: “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.”[4]

At the hazard of being thought one of the fools of this quotation, I meet that argument—I rush in, I take that bull by the horns.

I trust I understand, and truly estimate the right of self-government. My faith in the proposition that each man should do precisely as he pleases with all which is exclusively his own, lies at the foundation of the sense of justice there is in me. I extend the principles to communities of men, as well as to individuals. I so extend it, because it is politically wise, as well as naturally just; politically wise, in saving us from broils about matters which do not concern us. Here, or at Washington, I would not trouble myself with the oyster laws of Virginia, or the cranberry laws of Indiana.

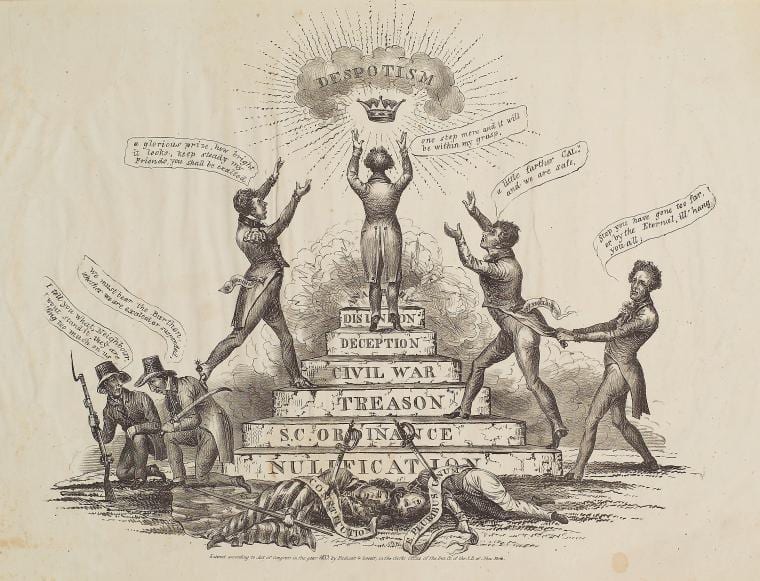

The doctrine of self-government is right—absolutely and eternally right—but it has no just application, as here attempted. Or perhaps I should rather say that whether it has such just application depends upon whether a Negro is not or is a man. If he is not a man, why in that case, he who is a man may, as a matter of self-government, do just as he pleases with him. But if the Negro is a man, is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself? When the white man governs himself that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism. If the Negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that “all men are created equal;” and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another. Judge Douglas frequently, with bitter irony and sarcasm, paraphrases our argument by saying “The white people of Nebraska are good enough to govern themselves, but they are not good enough to govern a few miserable Negroes!!”

Well I doubt not that the people of Nebraska are, and will continue to be as good as the average of people elsewhere. I do not say the contrary. What I do say is, that no man is good enough to govern another man, without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle—the sheet anchor of American republicanism. Our Declaration of Independence says:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

I have quoted so much at this time merely to show that according to our ancient faith, the just powers of governments are derived from the consent of the governed. Now the relation of masters and slaves is, pro tanto,[5] a total violation of this principle. The master not only governs the slave without his consent; but he governs him by a set of rules altogether different from those which he prescribes for himself. Allow ALL the governed an equal voice in the government, and that, and that only, is self-government.

Let it not be said I am contending for the establishment of political and social equality between the whites and blacks.[6] I have already said the contrary. I am not now combating the argument of necessity, arising from the fact that the blacks are already amongst us; but I am combating what is set up as moral argument for allowing them to be taken where they have never yet been—arguing against the extension of a bad thing, which where it already exists we must of necessity, manage as we best can.

In support of his application of the doctrine of self-government, Senator Douglas has sought to bring to his aid the opinions and examples of our revolutionary fathers. I am glad he has done this. I love the sentiments of those old-time men; and shall be most happy to abide by their opinions. He shows us that when it was in contemplation for the colonies to break off from Great Britain, and set up a new government for themselves, several of the states instructed their delegates to go for the measure provided each state should be allowed to regulate its domestic concerts in its own way. I do not quote; but this in substance. This was right. I see nothing objectionable in it. I also think it probable that it had some reference to the existence of slavery amongst them. I will not deny that it had. But had it, in any reference to the carrying of slavery into new countries? That is the question; and we will let the fathers themselves answer it.

This same generation of men, and mostly the same individuals of the generation, who declared this principle—who declared independence—who fought the war of the revolution through—who afterwards made the Constitution under which we still live—these same men passed the ordinance of ’87, declaring that slavery should never go to the north-west territory.[7] I have no doubt Judge Douglas thinks they were very inconsistent in this. It is a question of discrimination between them and him. But there is not an inch of ground left for his claiming that their opinions—their example—their authority—are on his side in this controversy. . . .

But you say this question should be left to the people of Nebraska, because they are more particularly interested. If this be the rule, you must leave it to each individual to say for himself whether he will have slaves. What better moral right have thirty-one citizens of Nebraska to say, that the thirty-second shall not hold slaves, than the people of the thirty-one states have to say that slavery shall not go into the thirty-second state at all?

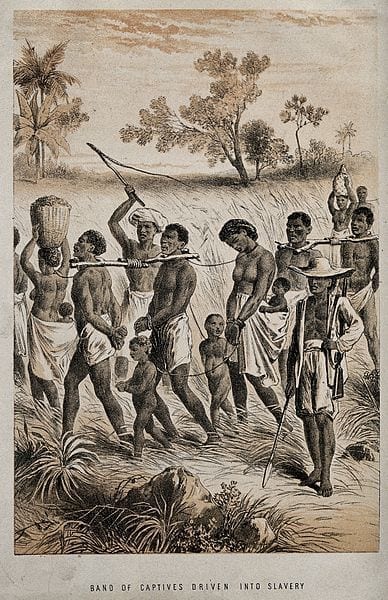

But if it is a sacred right for the people of Nebraska to take and hold slaves there, it is equally their sacred right to buy them where they can buy them cheapest; and that undoubtedly will be on the coast of Africa; provided you will consent to not hang them for going there to buy them. You must remove this restriction too, from the sacred right of self-government. I am aware you say that taking slaves from the [southern] states of [to?] Nebraska, does not make slaves of freemen; but the African slave trader can say just as much. He does not catch free Negroes and bring them here. He finds them already slaves in the hands of their black captors, and he honestly buys them at the rate of about a red cotton handkerchief a head. This is very cheap, and it is a great abridgement of the sacred right of self-government to hang men for engaging in this profitable trade!

Another important objection to this application of the right of self-government, is that it enables the first few, to deprive the succeeding many, of a free exercise of the right of self-government. The first few may get slavery in, and the subsequent many cannot easily get it out. How common is the remark now in the slave states—”If we were only clear of our slaves, how much better it would be for us.” They are actually deprived of the privilege of governing themselves as they would, by the action of a very few, in the beginning. The same thing was true of the whole nation at the time our Constitution was formed.

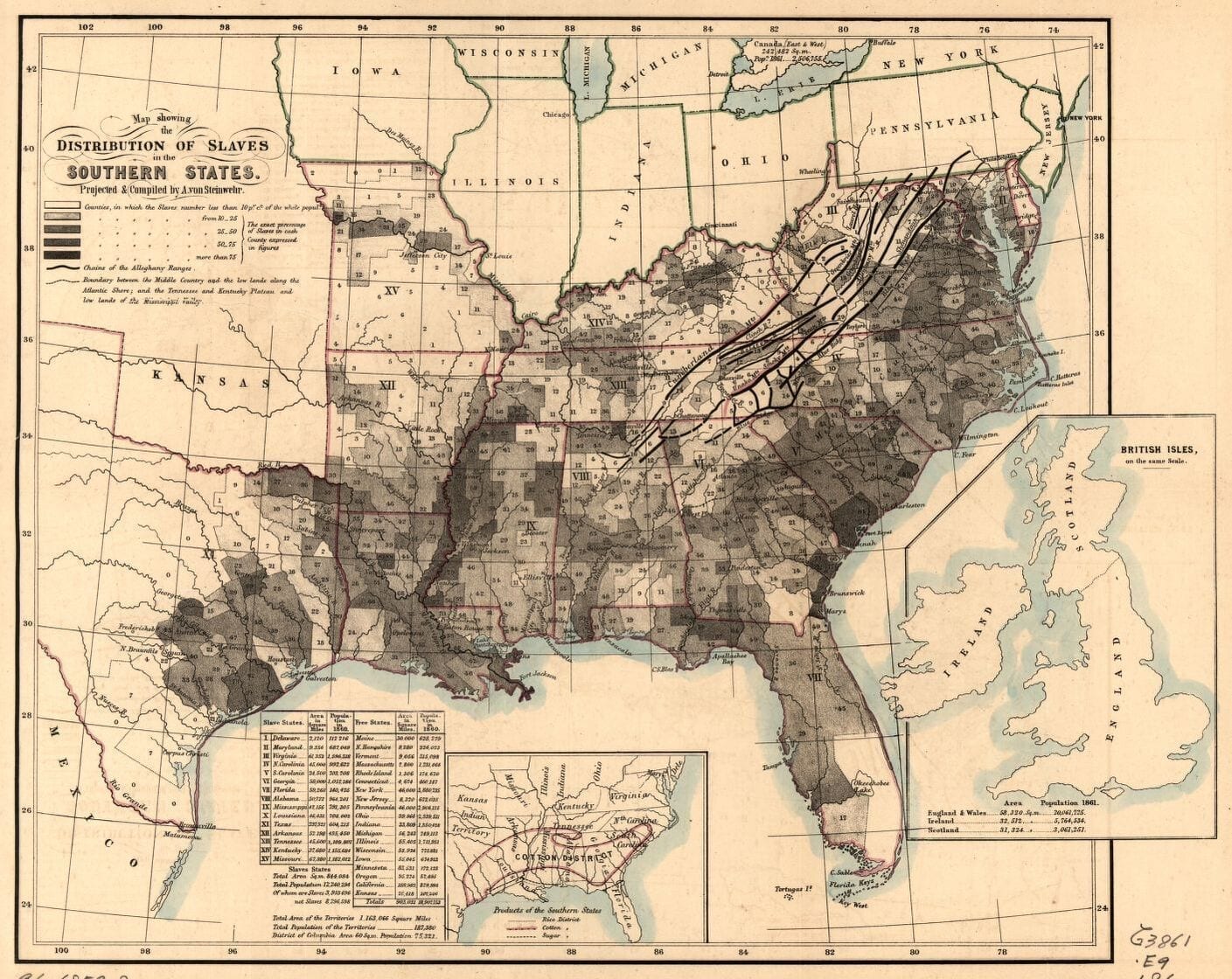

Whether slavery shall go into Nebraska, or other new territories, is not a matter of exclusive concern to the people who may go there. The whole nation is interested that the best use shall be made of these territories. We want them for the homes of free white people. This they cannot be, to any considerable extent, if slavery shall be planted within them. Slave states are places for poor white people to remove from; not to remove to. New free states are the places for poor people to go to and better their condition. For this use, the nation needs these territories.

Still further; there are constitutional relations between the slave and free states, which are degrading to the latter. We are under legal obligations to catch and return their runaway slaves to them—a sort of dirty, disagreeable job, which I believe, as a general rule the slaveholders will not perform for one another. Then again, in the control of the government—the management of the partnership affairs—they have greatly the advantage of us. By the Constitution, each state has two senators—each has a number of representatives, in proportion to the number of its people—and each has a number of presidential electors, equal to the whole number of its senators and representatives together. But in ascertaining the number of the people, for this purpose, five slaves are counted as being equal to three whites.[8] The slaves do not vote; they are only counted and so used, as to swell the influence of the white people’s votes. The practical effect of this is more aptly shown by a comparison of the states of South Carolina and Maine. South Carolina has six representatives and so has Maine; South Carolina has eight presidential electors, and so has Maine. This is precise equality so far; and, of course they are equal in senators, each having two. Thus in the control of the government, the two states are equals precisely. But how are they in the number of their white people? Maine has 581,813—while South Carolina has 274,567. Maine has twice as many as South Carolina, and 32,679 over. Thus each white man in South Carolina is more than the double of any man in Maine. This is all because South Carolina, besides her free people, has 384,984 slaves. The South Carolinian has precisely the same advantage over the white man in every other free state, as well as in Maine. He is more than the double of any one of us in this crowd. The same advantage, but not to the same extent, is held by all the citizens of the slave states, over those of the free; and it is an absolute truth, without an exception, that there is no voter in any slave state, but who has more legal power in the government, than any voter in any free state. There is no instance of exact equality; and the disadvantage is against us the whole chapter through. This principle, in the aggregate, gives the slave states, in the present Congress, twenty additional representatives—being seven more than the whole majority by which they passed the Nebraska bill.

Now all this is manifestly unfair; yet I do not mention it to complain of it, in so far as it is already settled. It is in the Constitution; and I do not, for that cause, or any other cause, propose to destroy, or alter, or disregard the Constitution. I stand to it, fairly, fully, and firmly.

But when I am told I must leave it altogether to other people to say whether new partners are to be bred up and brought into the firm, on the same degrading terms against me, I respectfully demur. I insist, that whether I shall be a whole man, or only, the half of one, in comparison with others, is a question in which I am somewhat concerned; and one which no other man can have a sacred right of deciding for me. If I am wrong in this—if it really be a sacred right of self-government, in the man who shall go to Nebraska, to decide whether he will be the equal of me or the double of me, then after he shall have exercised that right, and thereby shall have reduced me to a still smaller fraction of a man than I already am, I should like for some gentleman deeply skilled in the mysteries of sacred rights, to provide himself with a microscope, and peep about, and find out, if he can, what has become of my sacred rights! They will surely be too small for detection with the naked eye. Finally, I insist that if there is anything which it is the duty of the whole people to never entrust to any hands but their own, that thing is the preservation and perpetuity, of their own liberties, and institutions. And if they shall think, as I do, that the extension of slavery endangers them, more than any, or all other causes, how recreant to themselves, if they submit the question, and with it, the fate of their country, to a mere handful of men, bent only on temporary self-interest. If this question of slavery extension were an insignificant one—one having no power to do harm—it might be shuffled aside in this way. But being, as it is, the great Behemoth of danger, shall the strong gripe [grip?] of the nation be loosened upon him, to entrust him to the hands of such feeble keepers?

I have done with this mighty argument, of self-government. Go, sacred thing! Go in peace. . . .

I particularly object to the new position which the avowed principle of this Nebraska law gives to slavery in the body politic. I object to it because it assumes that there can be moral right in the enslaving of one man by another. I object to it as a dangerous dalliance for a free people—a sad evidence that, feeling prosperity we forget right—that liberty, as a principle, we have ceased to revere. I object to it because the fathers of the republic eschewed, and rejected it. The argument of “Necessity” was the only argument they ever admitted in favor of slavery; and so far, and so far only as it carried them, did they ever go. They found the institution existing among us, which they could not help; and they cast blame upon the British King for having permitted its introduction. Before the Constitution, they prohibited its introduction into the north-western Territory—the only country we owned, then free from it. At the framing and adoption of the Constitution, they forbore to so much as mention the word “slave” or “slavery” in the whole instrument. In the provision for the recovery of fugitives, the slave is spoken of as a “person held to service or labor.”[9] In that prohibiting the abolition of the African slave trade for twenty years, that trade is spoken of as “The migration or importation of such persons as any of the states now existing, shall think proper to admit,” &c.[10] These are the only provisions alluding to slavery. Thus, the thing is hid away, in the Constitution, just as an afflicted man hides away a wen or a cancer, which he dares not cut out at once, lest he bleed to death; with the promise, nevertheless, that the cutting may begin at the end of a given time. Less than this our fathers could not do; and more they would not do. Necessity drove them so far, and farther, they would not go. . . .

Thus we see, the plain unmistakable spirit of that age, towards slavery, was hostility to the principle, and toleration, only by necessity.

But now it is to be transformed into a “sacred right.” Nebraska brings it forth, places it on the high road to extension and perpetuity; and, with a pat on its back, says to it, “Go, and God speed you.” Henceforth it is to be the chief jewel of the nation—the very figure-head of the ship of state. Little by little, but steadily as man’s march to the grave, we have been giving up the old for the new faith. Near eighty years ago we began by declaring that all men are created equal; but now from that beginning we have run down to the other declaration, that for some men to enslave others is a “sacred right of self-government.” These principles cannot stand together. They are as opposite as God and mammon; and whoever holds to the one, must despise the other. When Pettit,[11] in connection with his support of the Nebraska bill, called the Declaration of Independence “a self-evident lie” he only did what consistency and candor require all other Nebraska men to do. Of the forty odd Nebraska senators who sat present and heard him, no one rebuked him. Nor am I apprized that any Nebraska newspaper, or any Nebraska orator, in the whole nation, has ever yet rebuked him. If this had been said among Marion’s men,[12] Southerners though they were, what would have become of the man who said it? If this had been said to the men who captured André, the man who said it, would probably have been hung sooner than André was.[13] If it had been said in old Independence Hall, seventy-eight years ago, the very door-keeper would have throttled the man, and thrust him into the street.

Let no one be deceived. The spirit of seventy-six and the spirit of Nebraska, are utter antagonisms; and the former is being rapidly displaced by the latter. Fellow countrymen—Americans south, as well as north, shall we make no effort to arrest this? Already the liberal party throughout the world, express the apprehension “that the one retrograde institution in America, is undermining the principles of progress, and fatally violating the noblest political system the world ever saw.”[14] This is not the taunt of enemies, but the warning of friends. Is it quite safe to disregard it—to despise it? Is there no danger to liberty itself, in discarding the earliest practice, and first precept of our ancient faith? In our greedy chase to make profit of the Negro, let us beware, lest we “cancel and tear to pieces”[15] even the white man’s charter of freedom.

Our republican robe is soiled, and trailed in the dust. Let us repurify it. Let us turn and wash it white, in the spirit, if not the blood, of the Revolution. Let us turn slavery from its claims of “moral right,” back upon its existing legal rights, and its arguments of “necessity.” Let us return it to the position our fathers gave it; and there let it rest in peace. Let us re-adopt the Declaration of Independence, and with it, the practices, and policy, which harmonize with it. Let North and South—let all Americans—let all lovers of liberty everywhere—join in the great and good work. If we do this, we shall not only have saved the Union; but we shall have so saved it, as to make, and to keep it, forever worthy of the saving. We shall have so saved it, that the succeeding millions of free happy people, the world over, shall rise up, and call us blessed, to the latest generations.

- 1. The Louisiana Purchase, 1803.

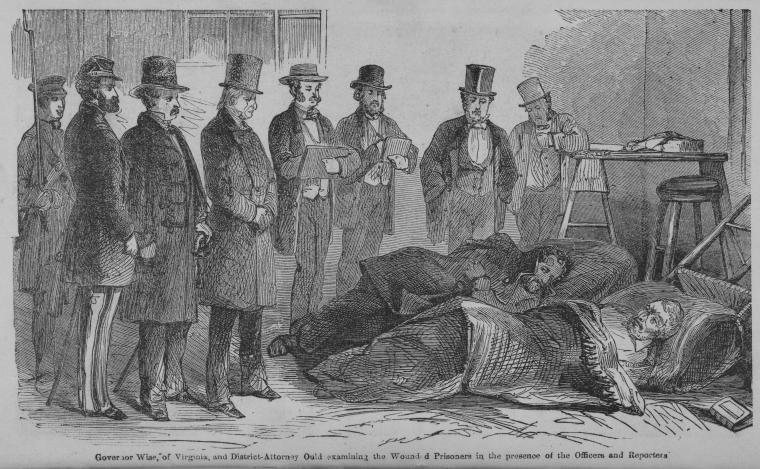

- 2. An Act to Protect the Commerce of the United States and Punish the Crime of Piracy, 1819, amended in 1820 to include participation in the slave trade as piracy. Nathaniel Gordon, captain of a ship carrying slaves from Africa, was captured by an American naval ship on an anti-slave trade patrol. He was tried and executed under the Act in 1862. President Lincoln refused to grant him a pardon.

- 3. Stephen A. Douglas.

- 4. Alexander Pope, An Essay on Criticism (1711).

- 5. to that extent.

- 6. Compare the argument in Document 27.

- 7. The Northwest Ordinance.

- 8. See The Three-Fifths Clause.

- 9. Article 4, section 2.

- 10. Article 1, section 9.

- 11. John Pettit (1807–1877) was a senator from Indiana.

- 12. Francis Marion (c. 1732–1795), nicknamed the “Swamp Fox,” was a famous commander of rebel forces in the Carolinas during the Revolutionary War.

- 13. John André (1750–1780) was a British officer hung as a spy during the Revolutionary War.

- 14. Apparently a paraphrase of a quotation from a newspaper article. See W. Caleb McDaniel, “New light on a Lincoln quote,” https://wcm1.web.rice.edu/ new-light-on-lincoln-quote.html.

- 15. Macbeth, Act III, Scene 2

Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise

October 16, 1854

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.