No related resources

Introduction

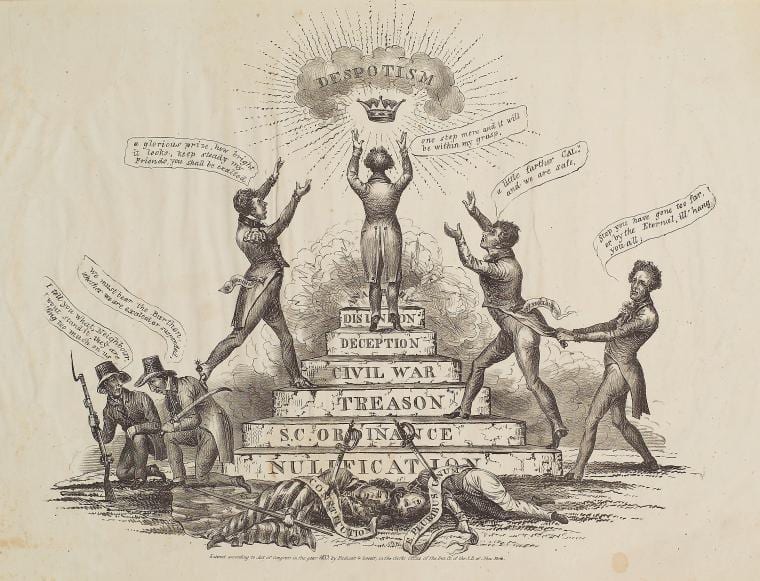

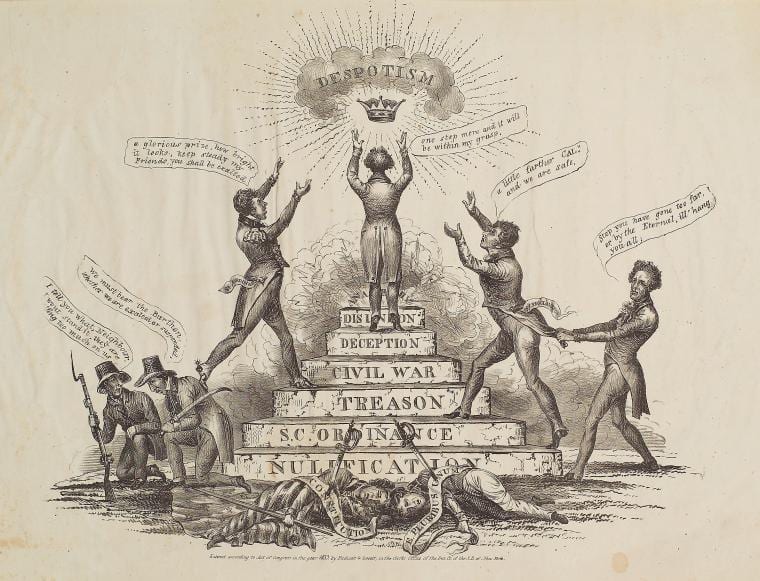

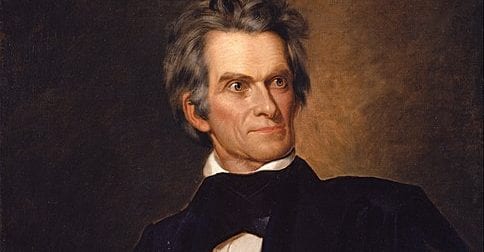

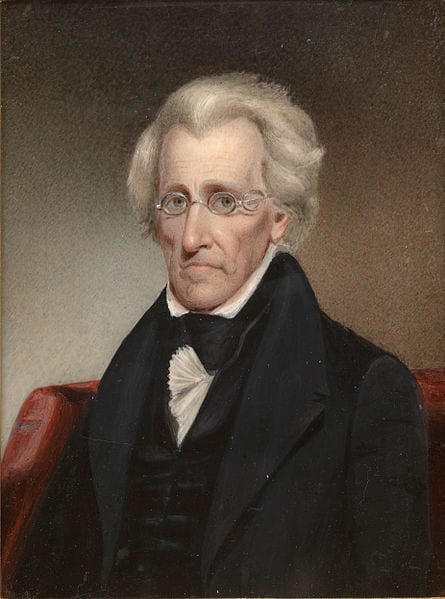

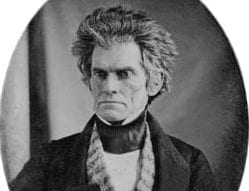

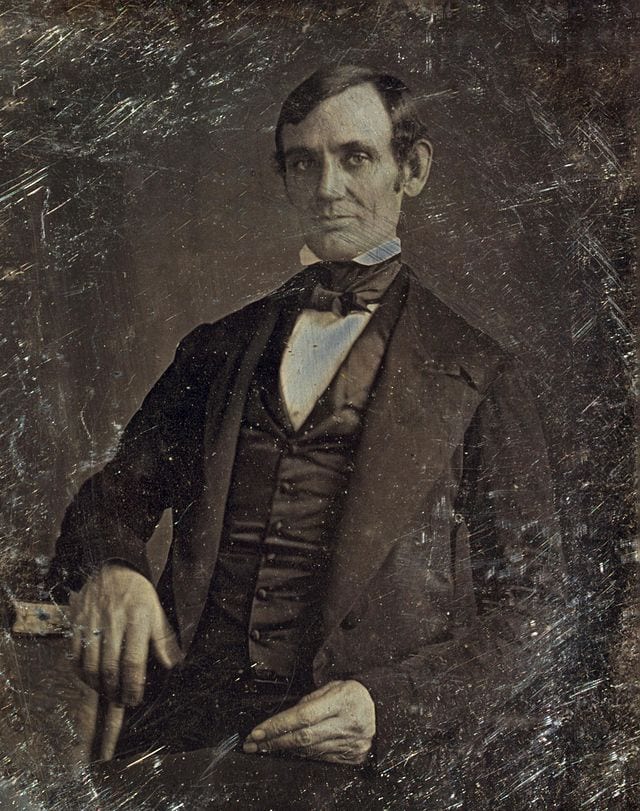

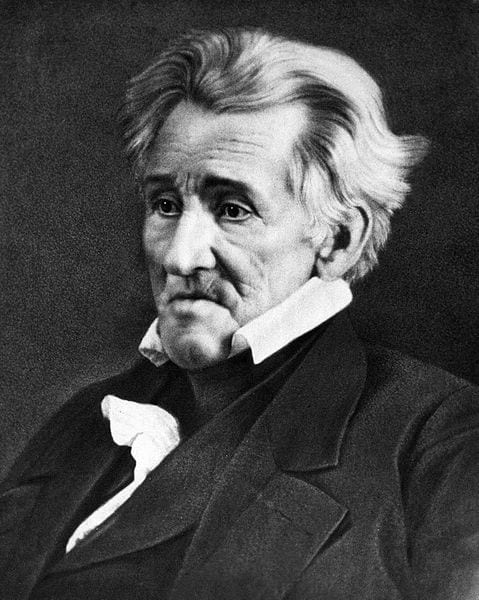

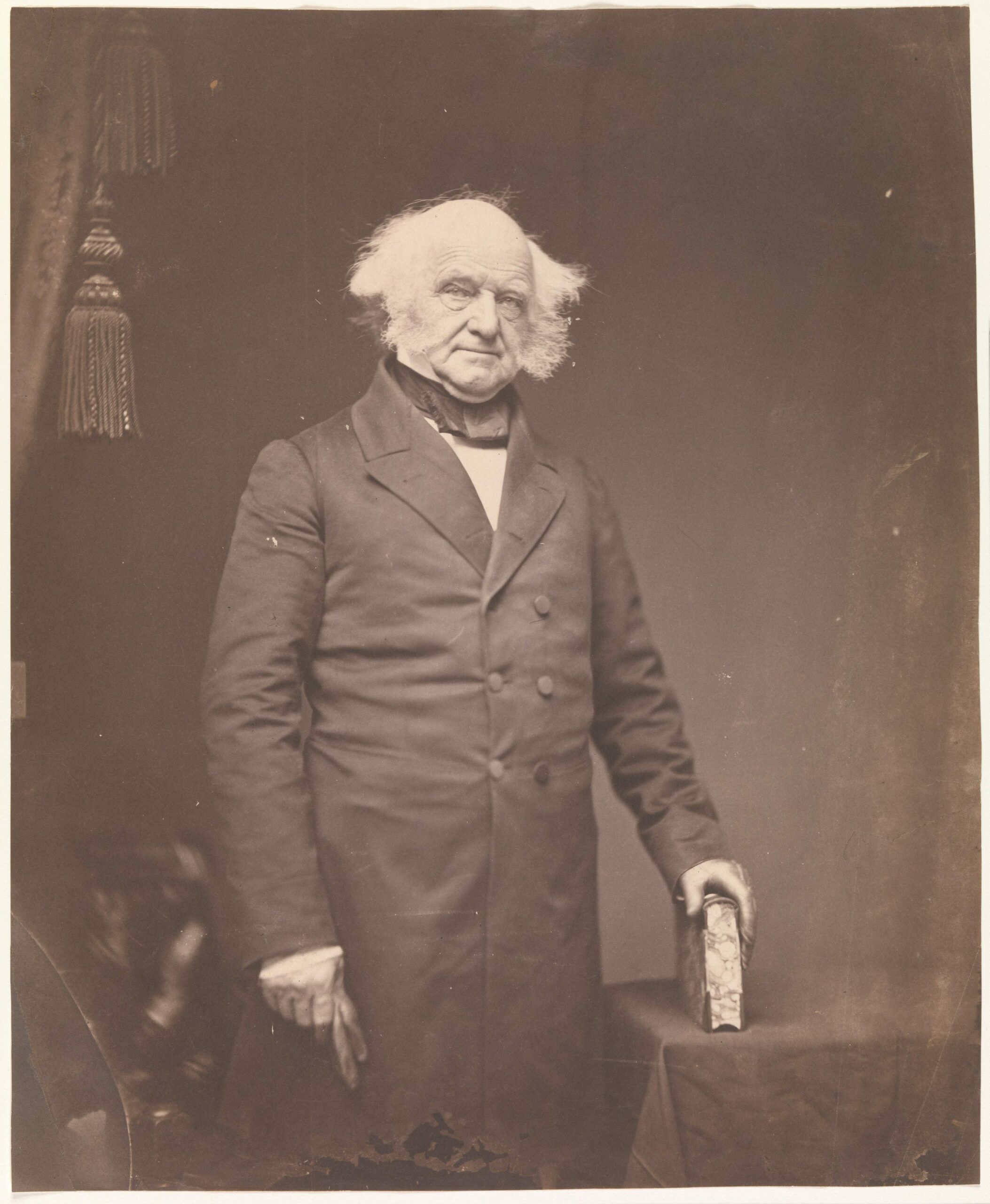

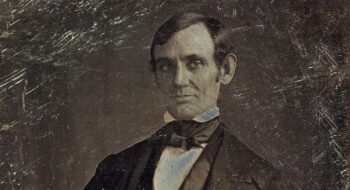

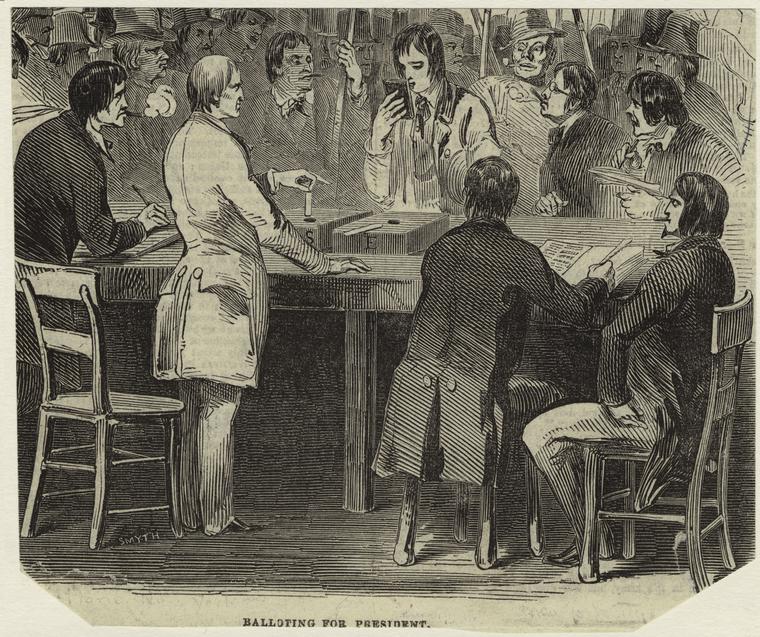

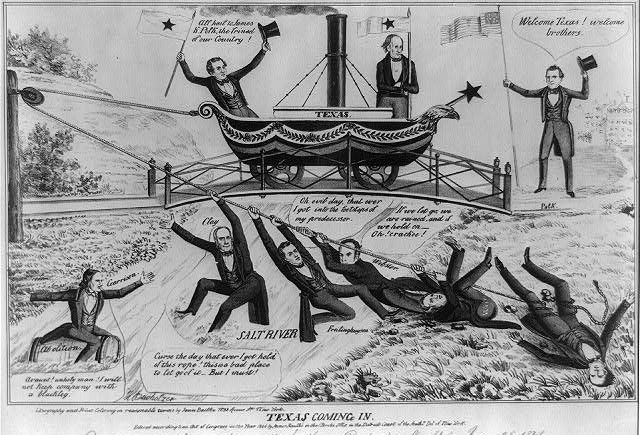

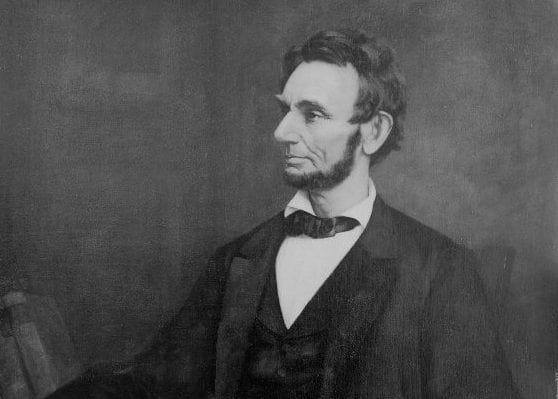

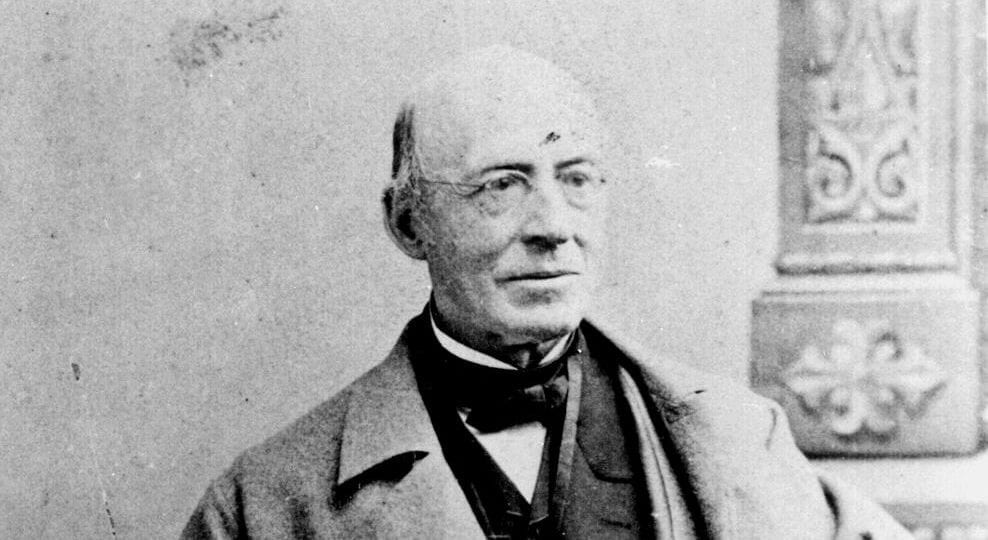

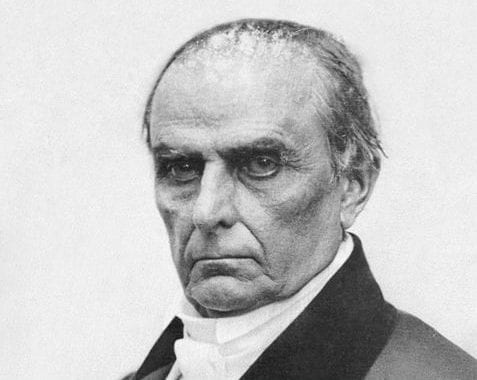

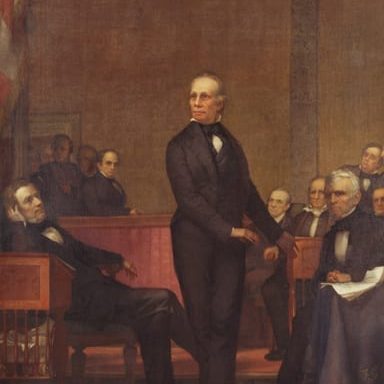

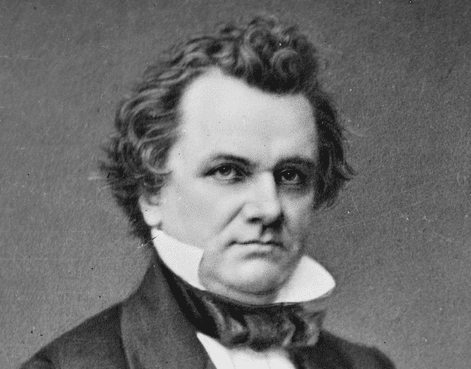

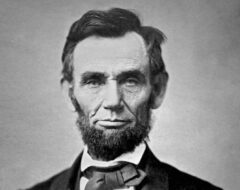

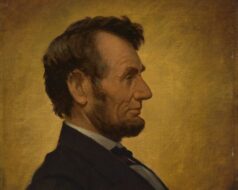

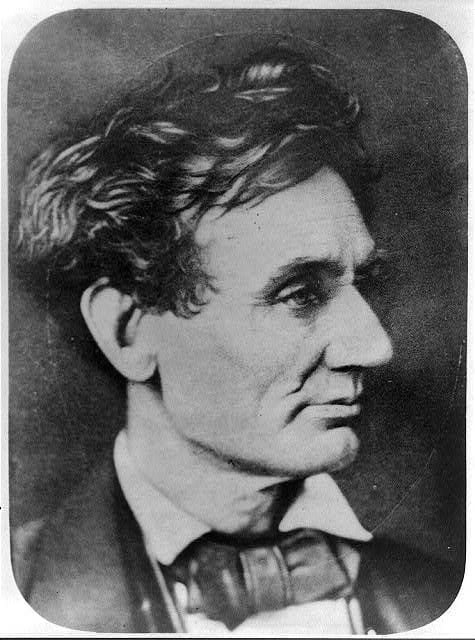

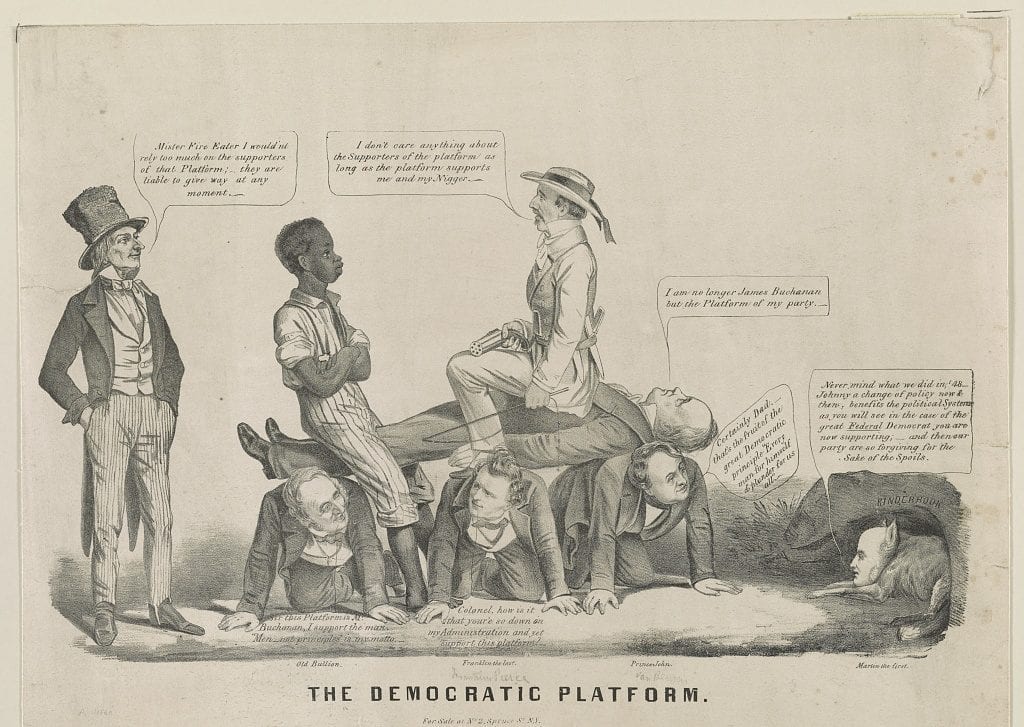

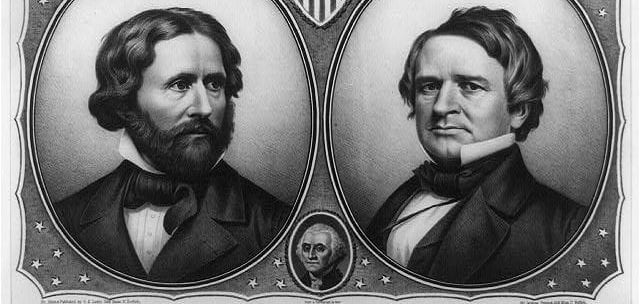

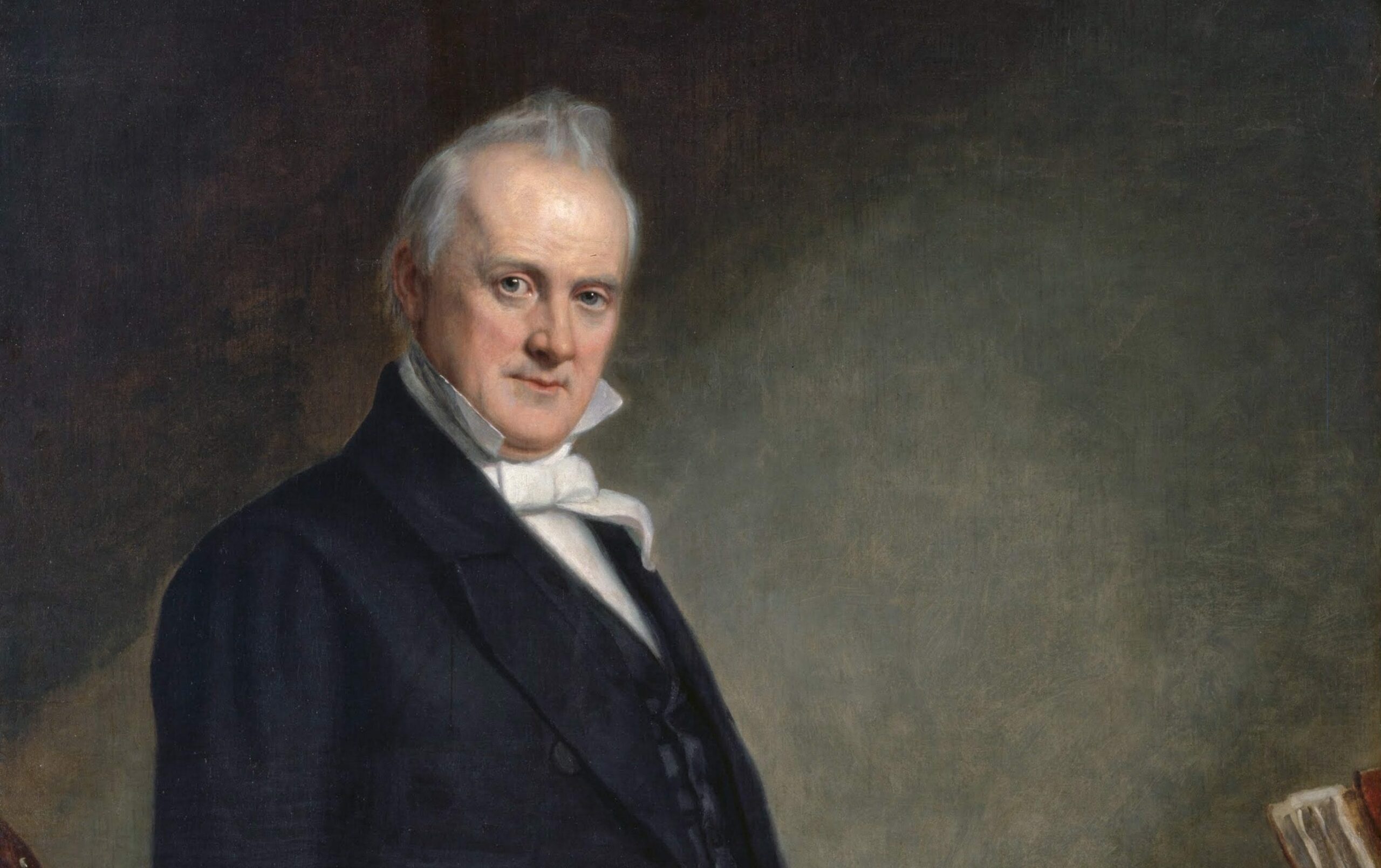

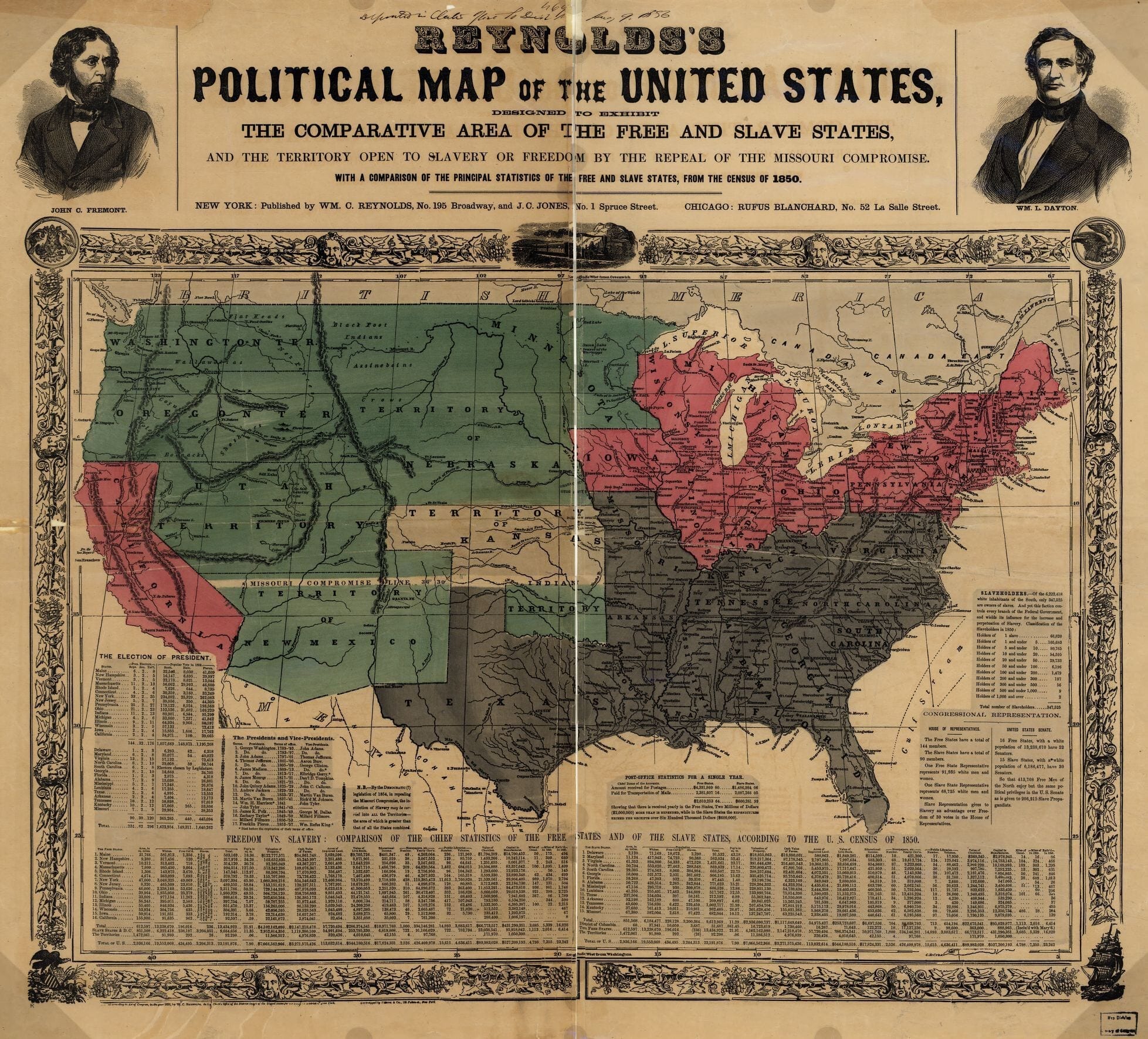

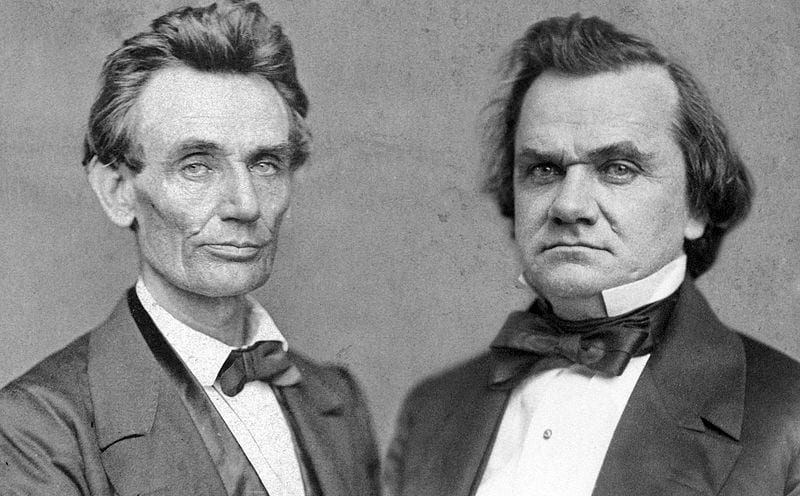

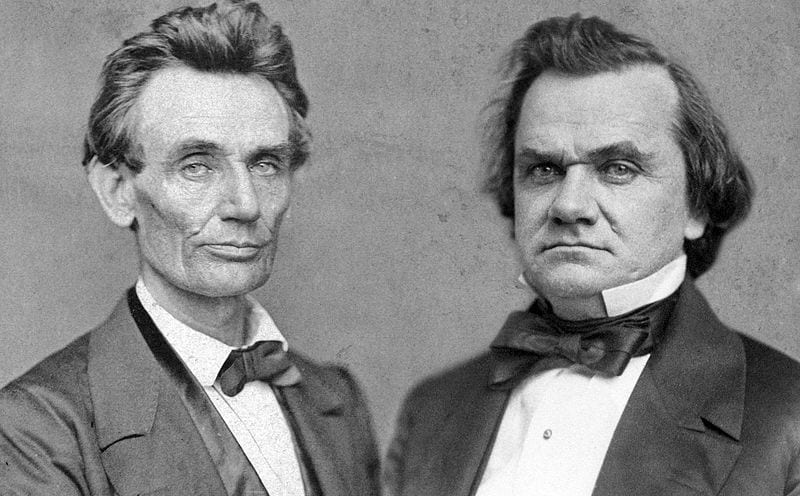

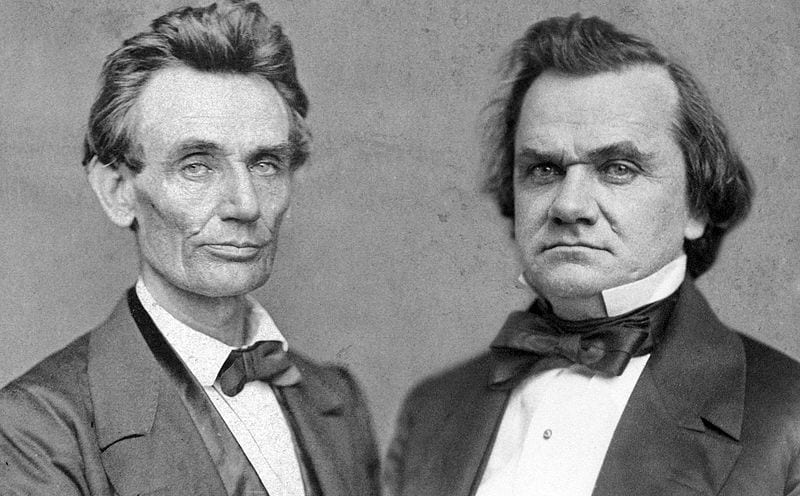

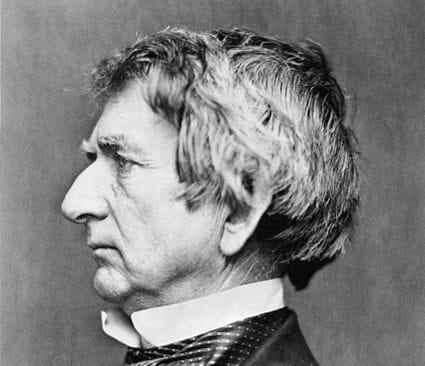

The Senate debates between Whig Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts and Democrat Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina in January 1830 started out as a disagreement over the sale of Western lands and turned into one of the most famous verbal contests in American history. During the course of the debates, the senators touched on pressing political issues of the day—the tariff, Western lands, internal improvements—because behind these and others were two very different understandings of the origin and nature of the American Union. Webster argued that the American people had created the Union to promote the good of the whole. Hayne argued that the sovereign and independent states had created the Union to promote their particular interests. Hayne maintained that the states retained the authority to nullify federal law, Webster that federal law expressed the will of the American people and could not be nullified by a minority of the people in a state. Nullification, Webster maintained, was a political absurdity. In this regard, Webster anticipated an argument that Abraham Lincoln made in his First Inaugural Address (1861). These irreconcilable views of national supremacy and state sovereignty framed the constitutional struggle that led to Civil War thirty years later. It is worth noting that in the course of the debate, on the very floor of the Senate, both Hayne and Webster raised the specter of civil war 30 years before it commenced.

Source: Daniel Webster, The Webster-Hayne Debate on the Nature of the Constitution: Selected Documents, ed. Herman Belz (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000). https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1557.

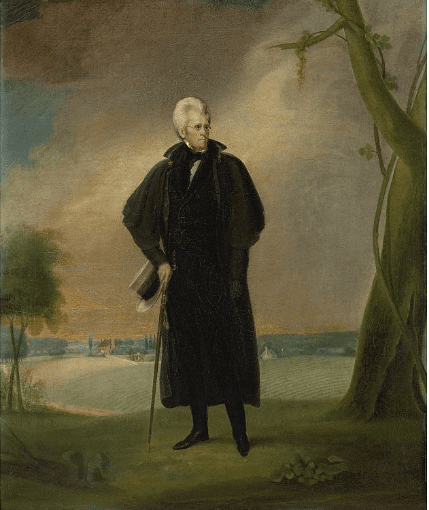

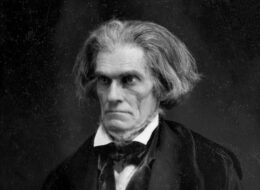

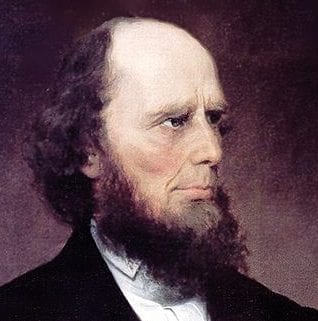

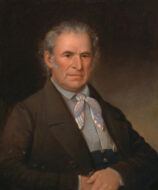

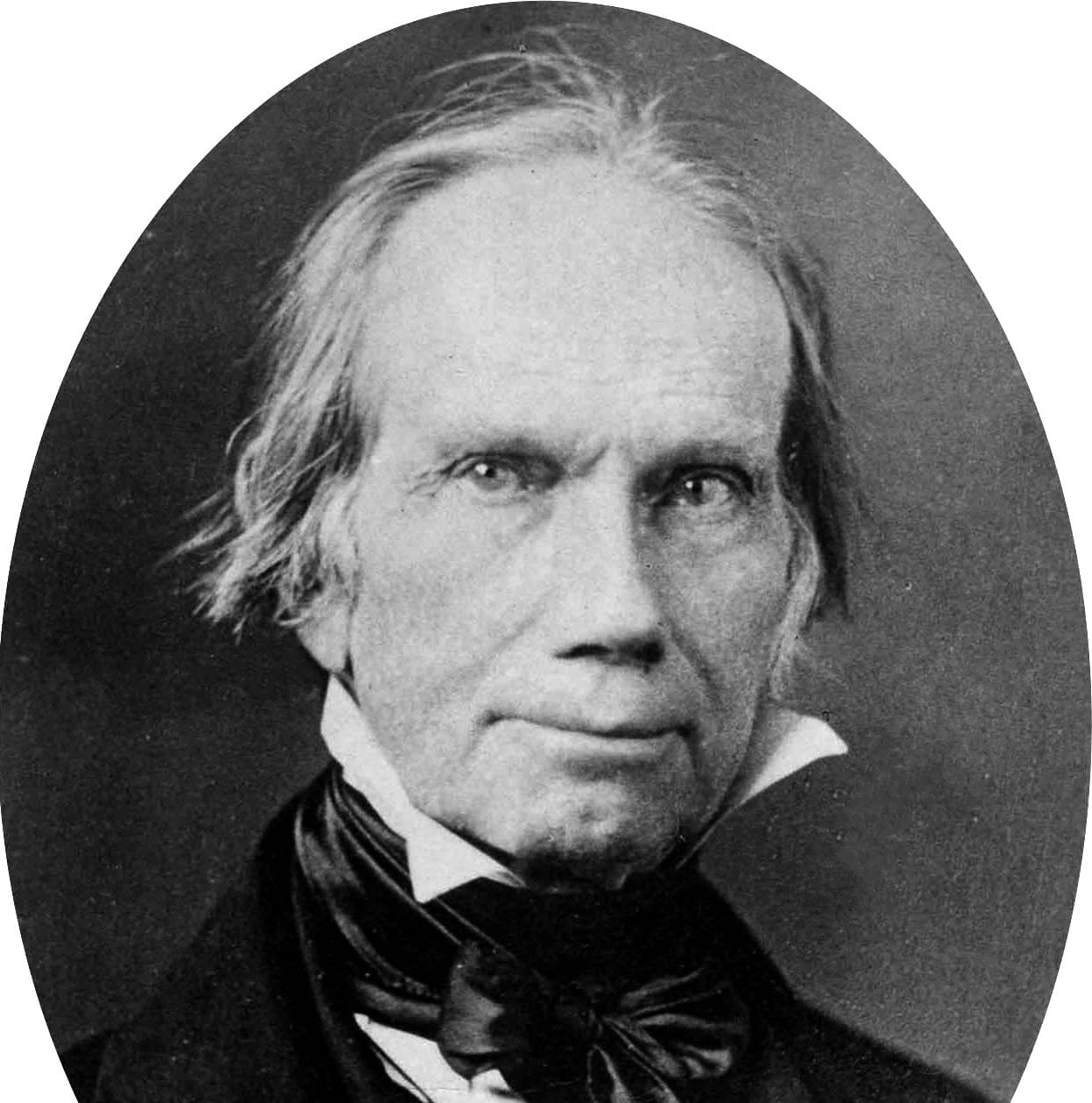

Speech of Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina, January 19, 1830

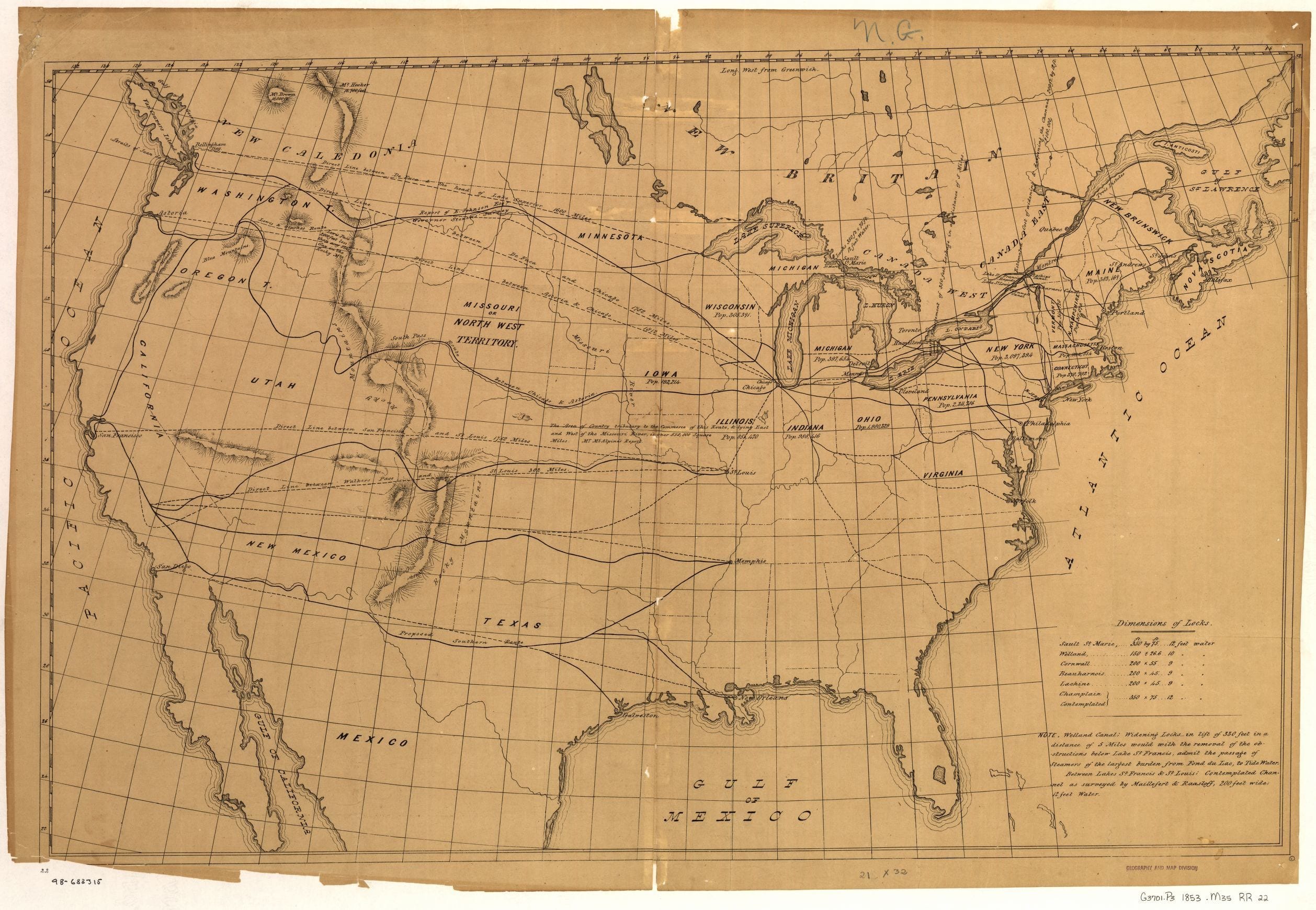

In coming to the consideration of the next great question, what ought to be the future policy of the government in relation to the public lands? we find the most opposite and irreconcilable opinions between the two parties which I have before described. On the one side it is contended that the public land ought to be reserved as a permanent fund for revenue, and future distribution among the states, while, on the other, it is insisted that the whole of these lands of right belong to, and ought to be relinquished to, the states in which they lie. . . . Will it promote the welfare of the United States to have at our disposal a permanent treasury, not drawn from the pockets of the people, but to be derived from a source independent of them? Would it be safe to confide such a treasure to the keeping of our national rulers? to expose them to the temptations inseparable from the direction and control of a fund which might be enlarged or diminished almost at pleasure, without imposing burthens upon the people? Sir, I may be singular—perhaps I stand alone here in the opinion, but it is one I have long entertained, that one of the greatest safeguards of liberty is a jealous watchfulness on the part of the people, over the collection and expenditure of the public money—a watchfulness that can only be secured where the money is drawn by taxation directly from the pockets of the people. Every scheme or contrivance by which rulers are able to procure the command of money by means unknown to, unseen or unfelt by, the people, destroys this security. Even the revenue system of this country, by which the whole of our pecuniary resources are derived from indirect taxation, from duties upon imports, has done much to weaken the responsibility of our federal rulers to the people, and has made them, in some measure, careless of their rights, and regardless of the high trust committed to their care. Can any man believe, sir, that, if twenty-three millions per annum was now levied by direct taxation, or by an apportionment of the same among the states, instead of being raised by an indirect tax, of the severe effect of which few are aware, that the waste and extravagance, the unauthorized imposition of duties, and appropriations of money for unconstitutional objects, would have been tolerated for a single year? My life upon it, sir, they would not. I distrust, therefore, sir, the policy of creating a great permanent national treasury, whether to be derived from public lands or from any other source. If I had, sir, the powers of a magician, and could, by a wave of my hand, convert this capital into gold for such a purpose, I would not do it. If I could, by a mere act of my will, put at the disposal of the federal government any amount of treasure which I might think proper to name, I should limit the amount to the means necessary for the legitimate purposes of the government. Sir, an immense national treasury would be a fund for corruption. It would enable Congress and the Executive to exercise a control over states, as well as over great interests in the country, nay, even over corporations and individuals—utterly destructive of the purity, and fatal to the duration of our institutions. It would be equally fatal to the sovereignty and independence of the states. Sir, I am one of those who believe that the very life of our system is the independence of the states, and that there is no evil more to be deprecated than the consolidation of this government. It is only by a strict adherence to the limitations imposed by the Constitution on the federal government, that this system works well, and can answer the great ends for which it was instituted. I am opposed, therefore, in any shape, to all unnecessary extension of the powers, or the influence of the Legislature or Executive of the Union over the states, or the people of the states; and, most of all, I am opposed to those partial distributions of favors, whether by legislation or appropriation, which has a direct and powerful tendency to spread corruption through the land; to create an abject spirit of dependence; to sow the seeds of dissolution; to produce jealousy among the different portions of the Union, and finally to sap the very foundations of the government itself. . . .

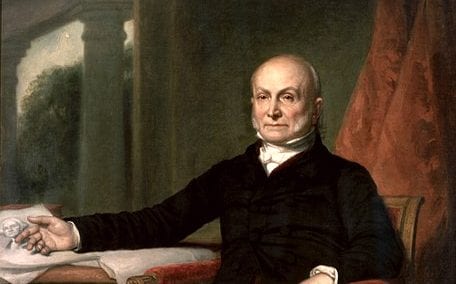

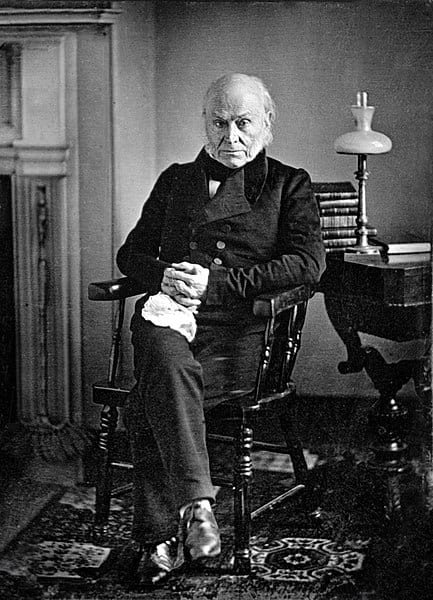

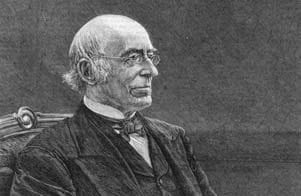

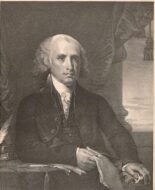

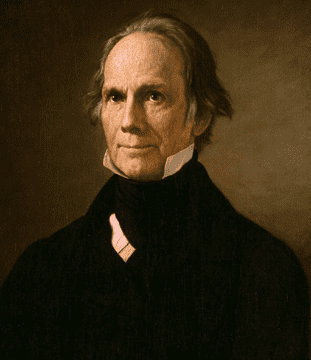

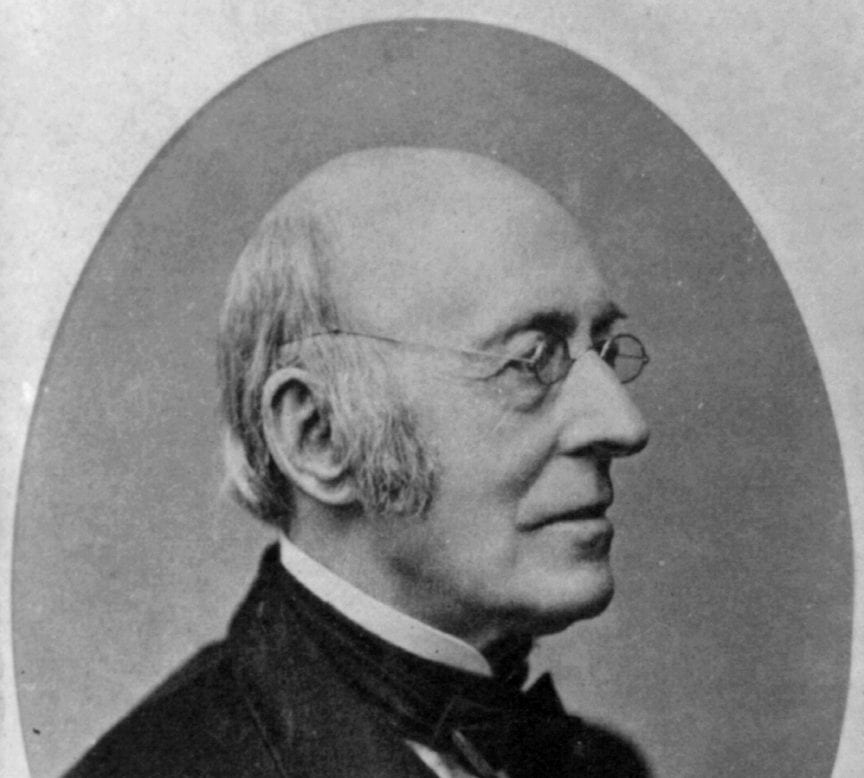

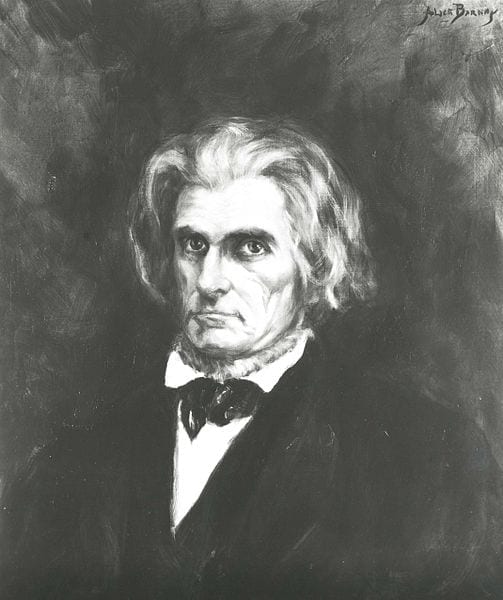

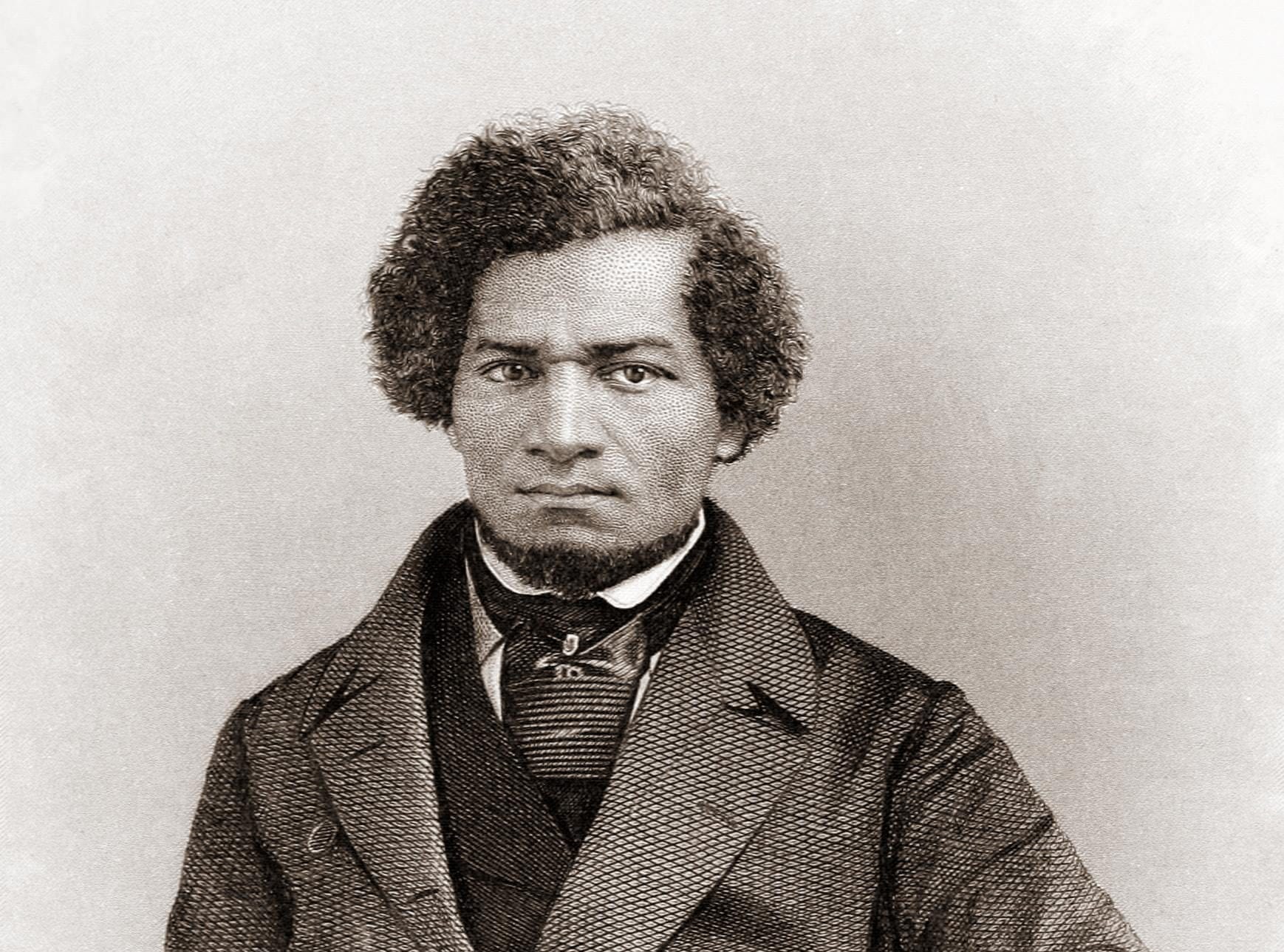

Speech of Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, January 20, 1830

[O]pinions were expressed yesterday on the general subject of the public lands, and on some other subjects, by the gentleman from South Carolina [Senator Robert Hayne], so widely different from my own, that I am not willing to let the occasion pass without some reply. . . .

. . . Consolidation!—that perpetual cry, both of terror and delusion—consolidation! Sir, when gentlemen speak of the effects of a common fund, belonging to all the states, as having a tendency to consolidation, what do they mean? Do they mean, or can they mean, anything more than that the Union of the states will be strengthened, by whatever continues or furnishes inducements to the people of the states to hold together? If they mean merely this, then, no doubt, the public lands as well as everything else in which we have a common interest, tends to consolidation; and to this species of consolidation every true American ought to be attached; it is neither more nor less than strengthening the Union itself. This is the sense in which the Framers of the Constitution use the word consolidation; and in which sense I adopt and cherish it. They tell us, in the letter submitting the Constitution to the consideration of the country, that, “in all our deliberations on this subject, we kept steadily in our view that which appears to us the greatest interest of every true American—the consolidation of our Union—in which is involved our prosperity, felicity, safety; perhaps our national existence. This important consideration, seriously and deeply impressed on our minds, led each state in the Convention to be less rigid, on points of inferior magnitude, than might have been otherwise expected.”

This, sir, is General Washington’s consolidation. This is the true constitutional consolidation. I wish to see no new powers drawn to the general government; but I confess I rejoice in whatever tends to strengthen the bond that unites us, and encourages the hope that our Union may be perpetual. And, therefore, I cannot but feel regret at the expression of such opinions as the gentleman has avowed; because I think their obvious tendency is to weaken the bond of our connection. I know that there are some persons in the part of the country from which the honorable member comes, who habitually speak of the Union in terms of indifference, or even of disparagement. The honorable member himself is not, I trust, and can never be, one of these. They significantly declare, that it is time to calculate the value of the Union; and their aim seems to be to enumerate, and to magnify all the evils, real and imaginary, which the government under the Union produces.

The tendency of all these ideas and sentiments is obviously to bring the Union into discussion, as a mere question of present and temporary expediency; nothing more than a mere matter of profit and loss. The Union to be preserved, while it suits local and temporary purposes to preserve it; and to be sundered whenever it shall be found to thwart such purposes. Union, of itself, is considered by the disciples of this school as hardly a good. It is only regarded as a possible means of good; or on the other hand, as a possible means of evil. They cherish no deep and fixed regard for it, flowing from a thorough conviction of its absolute and vital necessity to our welfare. Sir, I deprecate and deplore this tone of thinking and acting. I deem far otherwise of the Union of the states; and so did the Framers of the Constitution themselves. What they said I believe; fully and sincerely believe, that the Union of the states is essential to the prosperity and safety of the states. I am a Unionist, and in this sense a national Republican. I would strengthen the ties that hold us together. Far, indeed, in my wishes, very far distant be the day, when our associated and fraternal stripes shall be severed asunder, and when that happy constellation under which we have risen to so much renown, shall be broken up, and be seen sinking, star after star, into obscurity and night! . . .

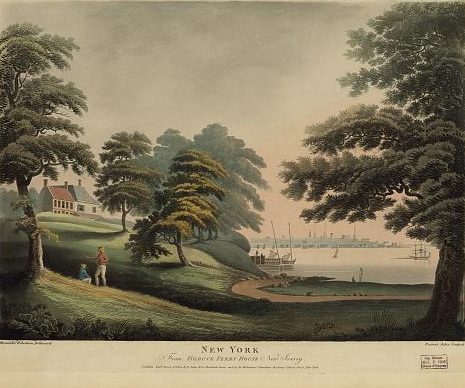

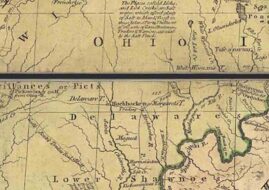

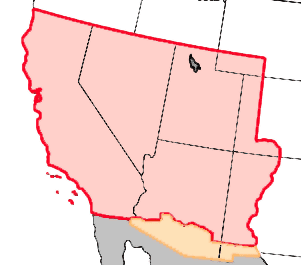

. . . I maintain that, from the day of the cession of the territories by the states to Congress, no portion of the country has acted, either with more liberality or more intelligence, on the subject of the Western lands in the new states, than New England. This statement, though strong, is no stronger than the strictest truth will warrant. Let us look at the historical facts. So soon as the cessions were obtained, it became necessary to make provision for the government and disposition of the territory . . . .

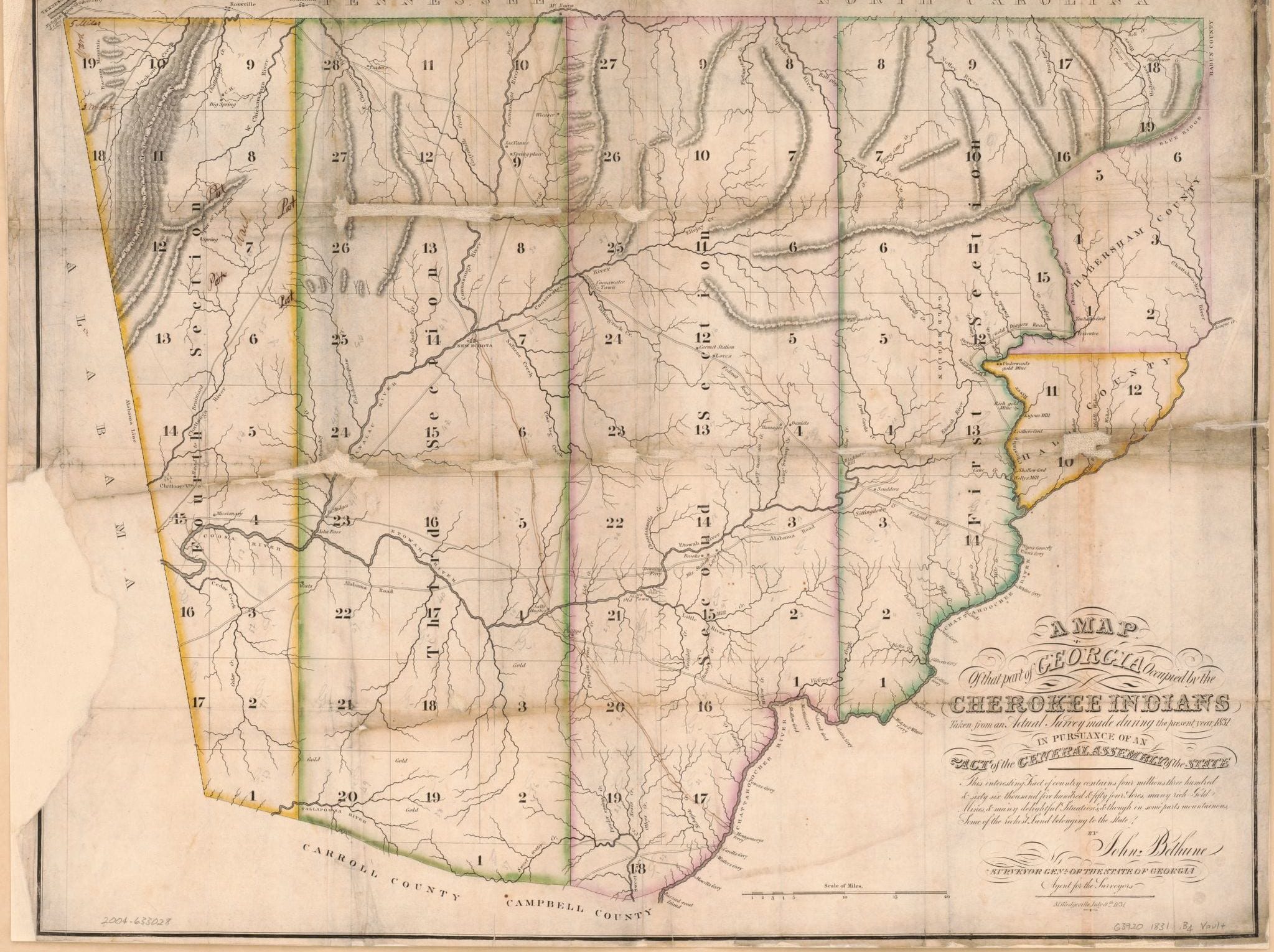

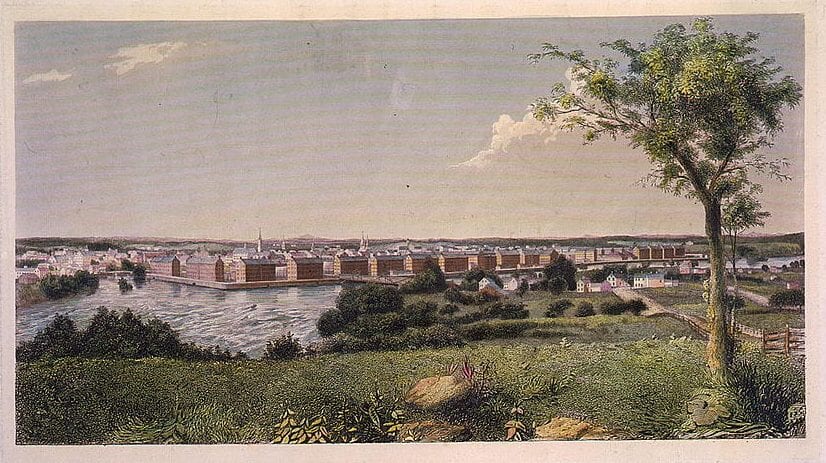

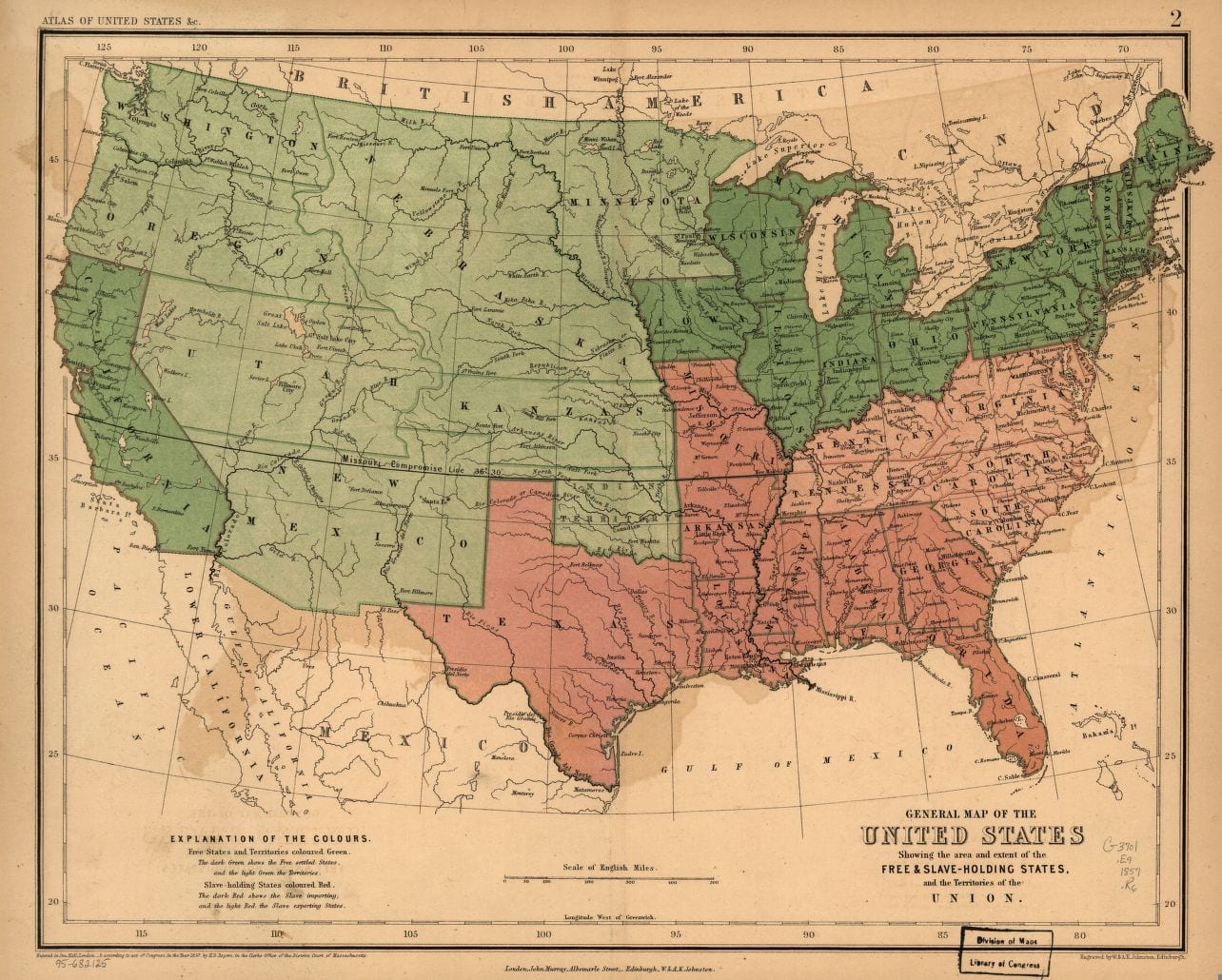

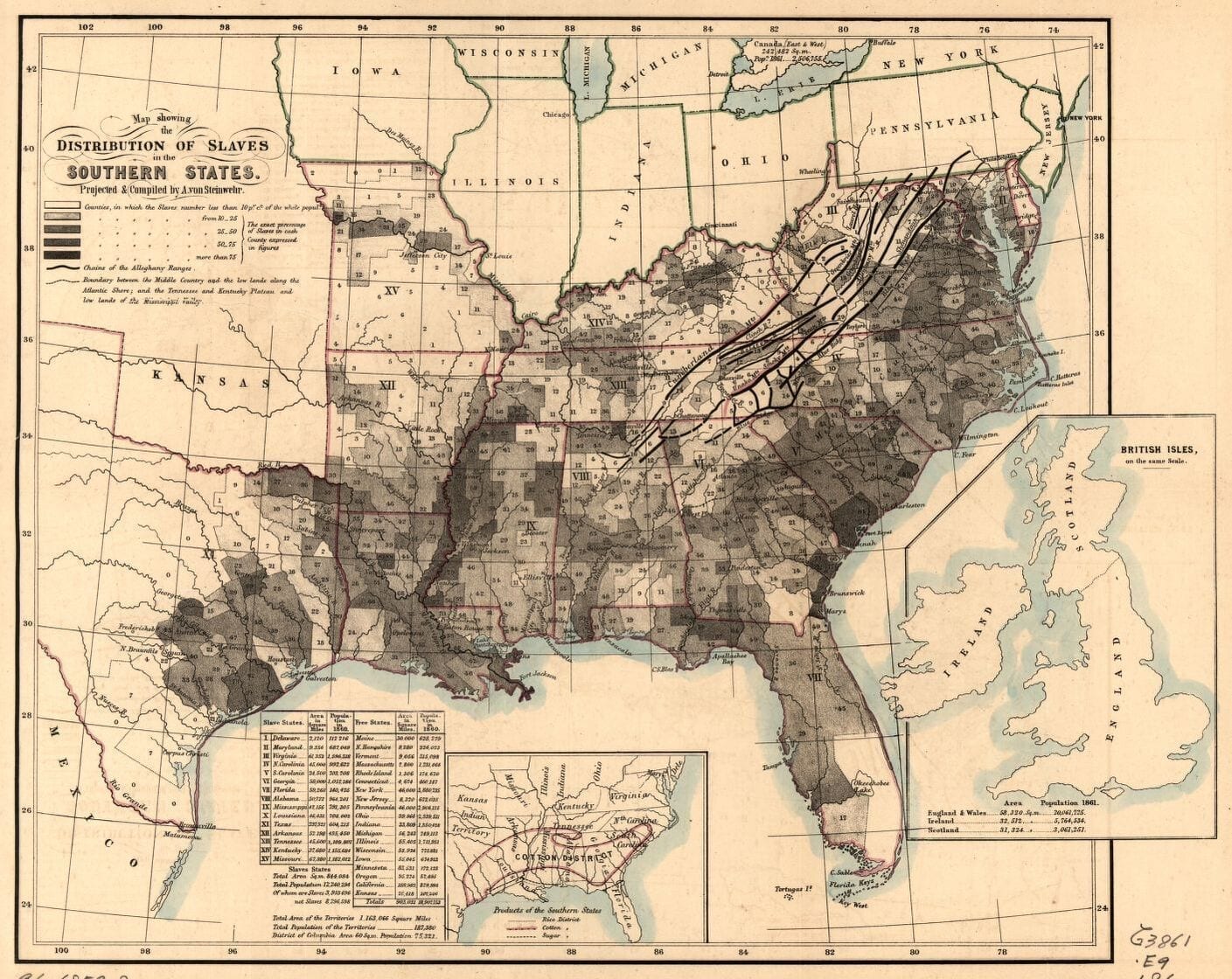

At the foundation of the constitution of these new Northwestern states, . . . [was] fixed, forever, the character of the population in the vast regions Northwest of the Ohio, by excluding from them involuntary servitude. It impressed on the soil itself, while it was yet a wilderness, an incapacity to bear up any other than free men. It laid the interdict against personal servitude, in original compact, not only deeper than all local law, but deeper, also, than all local constitutions. Under the circumstances then existing, I look upon this original and seasonable provision, as a real good attained. We see its consequences at this moment, and we shall never cease to see them, perhaps, while the Ohio shall flow. It was a great and salutary measure of prevention. Sir, I should fear the rebuke of no intelligent gentleman of Kentucky, were I to ask whether, if such an ordinance could have been applied to his own state, while it yet was a wilderness, and before Boone had passed the gap of the Alleghany, he does not suppose it would have contributed to the ultimate greatness of that commonwealth? . . .

Speech of Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina, January 25, 1830

. . . The honorable gentleman from Massachusetts [Senator Daniel Webster] has gone out of his way to pass a high eulogium on the state of Ohio. . . . To all this, sir, I was disposed most cordially to respond. When, however, the gentleman proceeded to contrast the state of Ohio with Kentucky, to the disadvantage of the latter, I listened to him with regret. . . . In contrasting the state of Ohio with Kentucky, for the purpose of pointing out the superiority of the former, and of attributing that superiority to the existence of slavery, in the one state, and its absence in the other, I thought I could discern the very spirit of the Missouri question[1] intruded into this debate, for objects best known to the gentleman himself. . . .

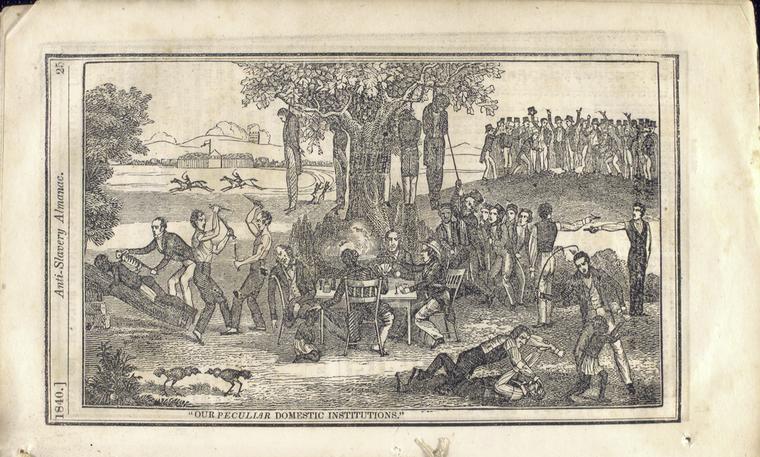

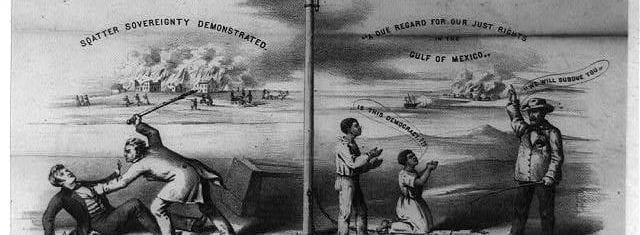

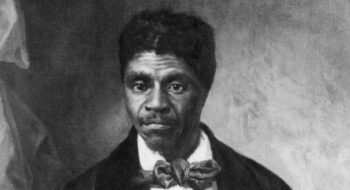

. . . The impression which has gone abroad, of the weakness of the South, as connected with the slave question, exposes us to such constant attacks, has done us so much injury, and is calculated to produce such infinite mischiefs, that I embrace the occasion presented by the remarks of the gentleman from Massachusetts, to declare that we are ready to meet the question promptly and fearlessly. It is one from which we are not disposed to shrink, in whatever form or under whatever circumstances it may be pressed upon us. We are ready to make up the issue with the gentleman, as to the influence of slavery on individual and national character—on the prosperity and greatness, either of the United States, or of particular states.

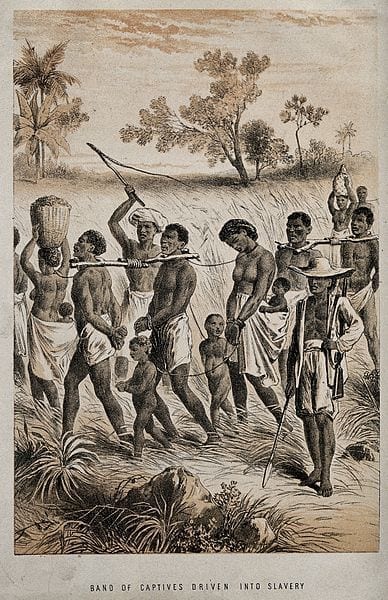

Sir, when arraigned before the bar of public opinion, on this charge of slavery, we can stand up with conscious rectitude, plead not guilty, and put ourselves upon God and our country. Sir, we will not stop to inquire whether the black man, as some philosophers have contended, is of an inferior race, nor whether his color and condition are the effects of a curse inflicted for the offences of his ancestors.[2] We deal in no abstractions. We will not look back to inquire whether our fathers were guiltless in introducing slaves into this country. If an inquiry should ever be instituted in these matters, however, it will be found that the profits of the slave trade were not confined to the South. Southern ships and Southern sailors were not the instruments of bringing slaves to the shores of America, nor did our merchants reap the profits of that “accursed traffic.”

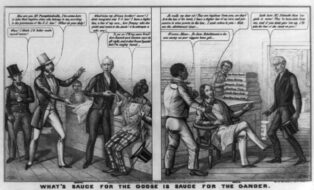

But, sir, we will pass over all this. If slavery, as it now exists in this country, be an evil, we of the present day found it ready made to our hands. Finding our lot cast among a people, whom God had manifestly committed to our care, we did not sit down to speculate on abstract questions of theoretical liberty. We met it as a practical question of obligation and duty. We resolved to make the best of the situation in which Providence had placed us, and to fulfil the high trust which had developed upon us as the owners of slaves, in the only way in which such a trust could be fulfilled, without spreading misery and ruin throughout the land. We found that we had to deal with a people whose physical, moral, and intellectual habits and character, totally disqualified them from the enjoyment of the blessings of freedom. We could not send them back to the shores from whence their fathers had been taken; their numbers forbade the thought, even if we did not know that their condition here is infinitely preferable to what it possibly could be among the barren sands and savage tribes of Africa; and it was wholly irreconcilable with all our notions of humanity to tear asunder the tender ties which they had formed among us, to gratify the feelings of a false philanthropy. What a commentary on the wisdom, justice, and humanity, of the Southern slave owner is presented by the example of certain benevolent associations and charitable individuals elsewhere. Shedding weak tears over sufferings which had existence only in their own sickly imaginations, these “friends of humanity” set themselves systematically to work to seduce the slaves of the South from their masters. By means of missionaries and political tracts, the scheme was in a great measure successful.

Thousands of these deluded victims of fanaticism were seduced into the enjoyment of freedom in our Northern cities. And what has been the consequence? Go to these cities now, and ask the question. Visit the dark and narrow lanes, and obscure recesses, which have been assigned by common consent as the abodes of those outcasts of the world—the free people of color. Sir, there does not exist, on the face of the whole earth, a population so poor, so wretched, so vile, so loathsome, so utterly destitute of all the comforts, conveniences, and decencies of life, as the unfortunate blacks of Philadelphia, and New York, and Boston. Liberty has been to them the greatest of calamities, the heaviest of curses. Sir, I have had some opportunities of making comparisons between the condition of the free Negroes of the North and the slaves of the South, and the comparison has left not only an indelible impression of the superior advantages of the latter, but has gone far to reconcile me to slavery itself. . . .

On this subject, as in all others, we ask nothing of our Northern brethren but to “let us alone;” leave us to the undisturbed management of our domestic concerns, and the direction of our own industry, and we will ask no more. Sir, all our difficulties on this subject have arisen from interference from abroad, which has disturbed, and may again disturb, our domestic tranquility, just so far as to bring down punishment upon the heads of the unfortunate victims of a fanatical and mistaken humanity. . . .

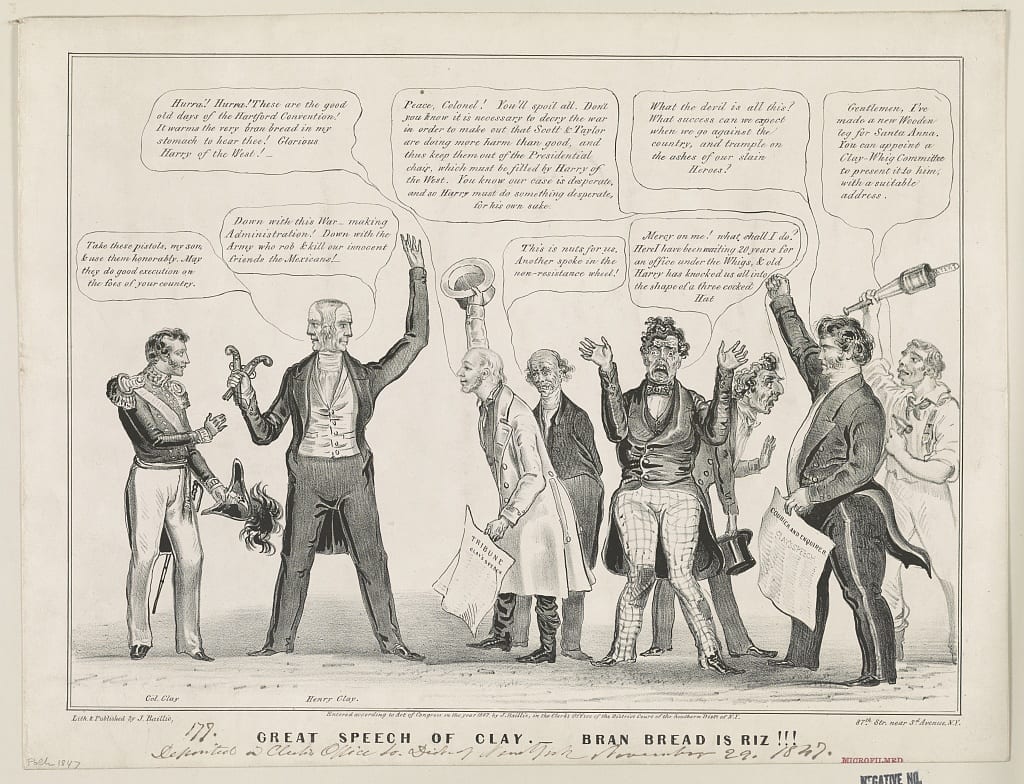

In the course of my former remarks, I took occasion to deprecate, as one of the greatest of evils, the consolidation of this government. The gentleman takes alarm at the sound. “Consolidation,” like the “tariff,” grates upon his ear. He tells us, “we have heard much, of late, about consolidation; that it is the rallying word for all who are endeavoring to weaken the Union by adding to the power of the states.” But consolidation, says the gentleman, was the very object for which the Union was formed; and in support of that opinion, he read a passage from the address of the president of the Convention[3] to Congress (which he assumes to be authority on his side of the question.) But, sir, the gentleman is mistaken. The object of the Framers of the Constitution, as disclosed in that address, was not the consolidation of the government, but “the consolidation of the Union.” It was not to draw power from the states, in order to transfer it to a great national government, but, in the language of the Constitution itself, “to form a more perfect union;” and by what means? By “establishing justice,” “promoting domestic tranquility,” and “securing the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” This is the true reading of the Constitution. But, according to the gentleman’s reading, the object of the Constitution was to consolidate the government, and the means would seem to be, the promotion of injustice, causing domestic discord, and depriving the states and the people “of the blessings of liberty” forever. . . .

The honorable gentleman from Massachusetts while he exonerates me personally from the charge, intimates that there is a party in the country who are looking to disunion. . . . Sir, when the gentleman provokes me to such a conflict, I meet him at the threshold. I will struggle while I have life, for our altars and our fire sides, and if God gives me strength, I will drive back the invader discomfited. Nor shall I stop there. If the gentleman provokes the war, he shall have war. Sir, I will not stop at the border; I will carry the war into the enemy’s territory, and not consent to lay down my arms, until I shall have obtained “indemnity for the past, and security for the future.”[4] It is with unfeigned reluctance that I enter upon the performance of this part of my duty. I shrink almost instinctively from a course, however necessary, which may have a tendency to excite sectional feelings, and sectional jealousies. But, sir, the task has been forced upon me, and I proceed right onward to the performance of my duty; be the consequences what they may, the responsibility is with those who have imposed upon me this necessity. . . .

Who, then, Mr. President, are the true friends of the Union? Those who would confine the federal government strictly within the limits prescribed by the Constitution—who would preserve to the states and the people all powers not expressly delegated—who would make this a federal and not a national Union—and who, administering the government in a spirit of equal justice, would make it a blessing and not a curse. And who are its enemies? Those who are in favor of consolidation; who are constantly stealing power from the states and adding strength to the federal government; who, assuming an unwarrantable jurisdiction over the states and the people, undertake to regulate the whole industry and capital of the country. . . .

The senator from Massachusetts, in denouncing what he is pleased to call the Carolina doctrine,[5] has attempted to throw ridicule upon the idea that a state has any constitutional remedy by the exercise of its sovereign authority against “a gross, palpable, and deliberate violation of the Constitution.” He called it “an idle” or “a ridiculous notion,” or something to that effect; and added, that it would make the Union “a mere rope of sand”. . . .

Sir, as to the doctrine that the federal government is the exclusive judge of the extent as well as the limitations of its powers, it seems to be utterly subversive of the sovereignty and independence of the states. It makes but little difference, in my estimation, whether Congress or the Supreme Court, are invested with this power. If the federal government, in all or any of its departments, are to prescribe the limits of its own authority; and the states are bound to submit to the decision, and are not to be allowed to examine and decide for themselves, when the barriers of the Constitution shall be overleaped, this is practically “a government without limitation of powers;” the states are at once reduced to mere petty corporations, and the people are entirely at your mercy. I have but one word more to add. In all the efforts that have been made by South Carolina to resist the unconstitutional laws which Congress has extended over them, she has kept steadily in view the preservation of the Union, by the only means by which she believes it can be long preserved—a firm, manly, and steady resistance against usurpation. The measures of the federal government have, it is true, prostrated her interests, and will soon involve the whole South in irretrievable ruin. . . .

Speech of Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, January 26 and 27, 1830

When the honorable member rose, in his first speech, I paid him the respect of attentive listening; and when he sat down, though surprised, and I must say even astonished, at some of his opinions, nothing was farther from my intention than to commence any personal warfare: and through the whole of the few remarks I made in answer, I avoided, studiously and carefully, everything which I thought possible to be construed into disrespect. . . .

I spoke, sir, of the ordinance of 1787, which prohibited slavery, in all future times, northwest of the Ohio,[6] as a measure of great wisdom and foresight; and one which had been attended with highly beneficial and permanent consequences. I supposed, that on this point, no two gentlemen in the Senate could entertain different opinions. But, the simple expression of this sentiment has led the gentleman, not only into a labored defense of slavery, in the abstract, and on principle, but, also, into a warm accusation against me, as having attacked the system of domestic slavery, now existing in the Southern states. For all this, there was not the slightest foundation, in anything said or intimated by me. I did not utter a single word, which any ingenuity could torture into an attack on the slavery of the South. I said, only, that it was highly wise and useful in legislating for the northwestern country, while it was yet a wilderness, to prohibit the introduction of slaves: and added, that I presumed, in the neighboring state of Kentucky, there was no reflecting and intelligent gentleman, who would doubt, that if the same prohibition had been extended, at the same early period, over that commonwealth, her strength and population would, at this day, have been far greater than they are. If these opinions be thought doubtful, they are, nevertheless, I trust, neither extraordinary nor disrespectful. They attack nobody, and menace nobody. . .

I know, full well, that it is, and has been, the settled policy of some persons in the South, for years, to represent the people of the North as disposed to interfere with them, in their own exclusive and peculiar concerns. This is a delicate and sensitive point, in southern feeling; and of late years it has always been touched, and generally with effect, whenever the object has been to unite the whole South against northern men, or northern measures. This feeling, always carefully kept alive, and maintained at too intense a heat to admit discrimination or reflection, is a lever of great power in our political machine. It moves vast bodies, and gives to them one and the same direction. But the feeling is without all adequate cause, and the suspicion which exists wholly groundless. There is not, and never has been, a disposition in the North to interfere with these interests of the South. Such interference has never been supposed to be within the power of government; nor has it been, in any way, attempted. It has always been regarded as a matter of domestic policy, left with the states themselves, and with which the federal government had nothing to do. Certainly, sir, I am, and ever have been of that opinion. The gentleman, indeed, argues that slavery, in the abstract, is no evil. Most assuredly, I need not say I differ with him, altogether and most widely, on that point. I regard domestic slavery as one of the greatest of evils, both moral and political. . . .

This leads, sir, to the real and wide difference, in political opinion, between the honorable gentleman and myself. . . . “What interest,” asks he, “has South Carolina in a canal in Ohio?” Sir, this very question is full of significance. It develops the gentleman’s whole political system; and its answer expounds mine. . . . On that system, Ohio and Carolina are different governments, and different countries, connected here, it is true, by some slight and ill-defined bond of union, but, in all main respects, separate and diverse. On that system, Carolina has no more interest in a canal in Ohio than in Mexico. The gentleman, therefore, only follows out his own principles; he does no more than arrive at the natural conclusions of his own doctrines; he only announces the true results of that creed, which he has adopted himself, and would persuade others to adopt, when he thus declares that South Carolina has no interest in a public work in Ohio.

Sir, we narrow-minded people of New England do not reason thus. Our notion of things is entirely different. We look upon the states, not as separated, but as united. We love to dwell on that union, and on the mutual happiness which it has so much promoted, and the common renown which it has so greatly contributed to acquire. In our contemplation, Carolina and Ohio are parts of the same country; states, united under the same general government, having interests, common, associated, intermingled. In whatever is within the proper sphere of the constitutional power of this government, we look upon the states as one. We do not impose geographical limits to our patriotic feeling or regard; we do not follow rivers and mountains, and lines of latitude, to find boundaries, beyond which public improvements do not benefit us. We who come here, as agents and representatives of these narrow-minded and selfish men of New England, consider ourselves as bound to regard, with equal eye, the good of the whole, in whatever is within our power of legislation. . . .

There yet remains to be performed, Mr. President, by far the most grave and important duty, which I feel to be devolved on me, by this occasion. It is to state, and to defend, what I conceive to be the true principles of the Constitution under which we are here assembled. . . .

I understand the honorable gentleman from South Carolina to maintain, that it is a right of the state legislatures to interfere, whenever, in their judgment, this government transcends its constitutional limits, and to arrest the operation of its laws.

I understand him to maintain this right, as a right existing under the Constitution; not as a right to overthrow it, on the ground of extreme necessity, such as would justify violent revolution.

I understand him to maintain an authority, on the part of the states, thus to interfere, for the purpose of correcting the exercise of power by the general government, of checking it, and of compelling it to conform to their opinion of the extent of its powers.

I understand him to maintain, that the ultimate power of judging of the constitutional extent of its own authority, is not lodged exclusively in the general government, or any branch of it; but that, on the contrary, the states may lawfully decide for themselves, and each state for itself, whether, in a given case, the act of the general government transcends its power.

I understand him to insist, that if the exigency of the case, in the opinion of any state government, require it, such state government may, by its own sovereign authority, annul an act of the general government, which it deems plainly and palpably unconstitutional.

This is the sum of what I understand from him, to be the South Carolina doctrine; and the doctrine which he maintains. I propose to consider it, and to compare it with the Constitution. Allow me to say, as a preliminary remark, that I call this the South Carolina doctrine, only because the gentleman himself has so denominated it. . . .

We, sir, who oppose the Carolina doctrine, do not deny that the people may, if they choose, throw off any government, when it becomes oppressive and intolerable, and erect a better in its stead. We all know that civil institutions are established for the public benefit, and that when they cease to answer the ends of their existence, they may be changed. But I do not understand the doctrine now contended for to be that which, for the sake of distinctness, we may call the right of revolution. I understand the gentleman to maintain, that, without revolution, without civil commotion, without rebellion, a remedy for supposed abuse and transgression of the powers of the general government lies in a direct appeal to the interference of the state governments. . . .

. . . I say, the right of a state to annul a law of Congress, cannot be maintained, but on the ground of the unalienable right of man to resist oppression; that is to say, upon the ground of revolution. I admit that there is an ultimate violent remedy, above the Constitution, and in defiance of the Constitution, which may be resorted to, when a revolution is to be justified. But I do not admit that, under the Constitution, and in conformity with it, there is any mode in which a state government, as a member of the Union, can interfere and stop the progress of the general government, by force of her own laws, under any circumstances whatever.

This leads us to inquire into the origin of this government, and the source of its power. Whose agent is it? Is it the creature of the state legislatures, or the creature of the people? If the government of the United States be the agent of the state governments, then they may control it, provided they can agree in the manner of controlling it; if it be the agent of the people, then the people alone can control it, restrain it, modify, or reform it. It is observable enough, that the doctrine for which the honorable gentleman contends, leads him to the necessity of maintaining, not only that this general government is the creature of the states, but that it is the creature of each of the states severally; so that each may assert the power, for itself, of determining whether it acts within the limits of its authority. It is the servant of four-and-twenty masters, of different wills and different purposes, and yet bound to obey all. This absurdity (for it seems no less) arises from a misconception as to the origin of this government and its true character. It is, sir, the people’s Constitution, the people’s government; made for the people; made by the people; and answerable to the people. The people of the United States have declared that this Constitution shall be the Supreme Law. . . .

I must now beg to ask, sir, whence is this supposed right of the states derived?—where do they find the power to interfere with the laws of the Union? Sir, the opinion which the honorable gentleman maintains, is a notion, founded in a total misapprehension, in my judgment, of the origin of this government, and of the foundation on which it stands. I hold it to be a popular government, erected by the people; those who administer it responsible to the people; and itself capable of being amended and modified, just as the people may choose it should be. . . . This government, sir, is the independent offspring of the popular will. It is not the creature of state Legislatures; nay, more, if the whole truth must be told, the people brought it into existence, established it, and have hitherto supported it, for the very purpose, amongst others, of imposing certain salutary restraints on state sovereignties. The states cannot now make war; they cannot contract alliances; they cannot make, each for itself, separate regulations of commerce; they cannot lay imposts; they cannot coin money. If this Constitution, sir, be the creature of state Legislatures, it must be admitted that it has obtained a strange control over the volitions of its creators. . . .

Sir, the very chief end, the main design, for which the whole Constitution was framed and adopted, was to establish a government that should not be obliged to act through state agency, or depend on state opinion and state discretion. The people had had quite enough of that kind of government, under the Confederacy. Under that system, the legal action—the application of law to individuals, belonged exclusively to the states. Congress could only recommend—their acts were not of binding force, till the states had adopted and sanctioned them. Are we in that condition still? Are we yet at the mercy of state discretion, and state construction? Sir, if we are, then vain will be our attempt to maintain the Constitution under which we sit. . . .

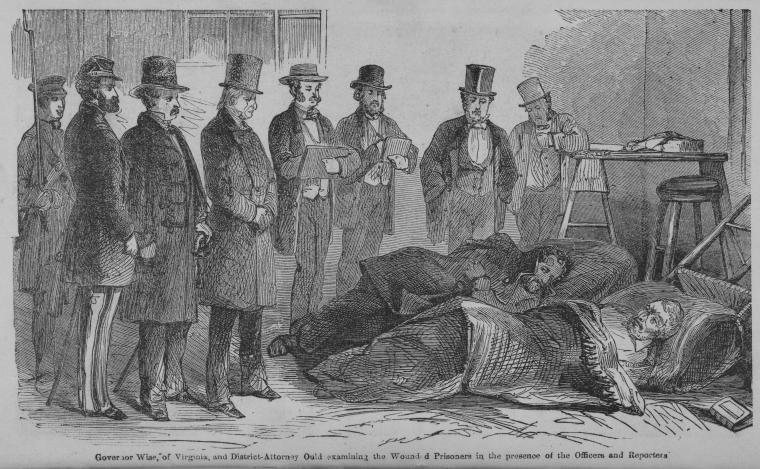

And now, Mr. President, let me run the honorable gentleman’s doctrine a little into its practical application. Let us look at his probable modus operandi. . . . Now, I wish to be informed how this state interference is to be put in practice, without violence, bloodshed, and rebellion. . . . The militia of the state will be called out to sustain the nullifying act. . . . [Its leader] would have a knot before him, which he could not untie. He must cut it with his sword. He must say to his followers [members of the state militia], defend yourselves with your bayonets; and this is war—civil war. . . .

While the Union lasts, we have high, exciting, gratifying prospects spread out before us, for us and our children. Beyond that I seek not to penetrate the veil. God grant that, in my day, at least, that curtain may not rise. God grant that on my vision never may be opened what lies behind. When my eyes shall be turned to behold, for the last time, the sun in Heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on states dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent with civil feuds, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood! Let their last feeble and lingering glance, rather behold the gorgeous Ensign of the Republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, still full high advanced, its arms and trophies streaming in their original luster, not a stripe erased or polluted, nor a single star obscured—bearing for its motto, no such miserable interrogatory as, what is all this worth? Nor those other words of delusion and folly, liberty first, and union afterwards—but everywhere, spread all over in characters of living light, blazing on all its ample folds, as they float over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole Heavens, that other sentiment, dear to every true American heart—liberty and union, now and forever, one and inseparable!

Mr. Hayne having rejoined to Mr. Webster, especially on the constitutional question—

Mr. Webster arose, and, in conclusion, said: A few words, Mr. President, on this constitutional argument, which the honorable gentleman has labored to reconstruct. . . .

When the gentleman says the Constitution is a compact between the states, he uses language exactly applicable to the old Confederation. He speaks as if he were in Congress before 1789. He describes fully that old state of things then existing. The Confederation was, in strictness, a compact; the states, as states, were parties to it. We had no other general government. But that was found insufficient, and inadequate to the public exigencies. The people were not satisfied with it, and undertook to establish a better. They undertook to form a general government, which should stand on a new basis—not a confederacy, not a league, not a compact between states, but a Constitution; a popular government, founded in popular election, directly responsible to the people themselves, and divided into branches, with prescribed limits of power, and prescribed duties. They ordained such a government; they gave it the name of a Constitution, and therein they established a distribution of powers between this, their general government, and their several state governments. When they shall become dissatisfied with this distribution, they can alter it. Their own power over their own instrument remains. But until they shall alter it, it must stand as their will, and is equally binding on the general government and on the states. . .

Finally, sir, the honorable gentleman says, that the states will only interfere, by their power, to preserve the Constitution. They will not destroy it, they will not impair it—they will only save, they will only preserve, they will only strengthen it! Ah! sir, this is but the old story. All regulated governments, all free governments, have been broken up by similar disinterested and well-disposed interference! It is the common pretense. But I take leave of the subject.

Speech of Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina, January 27, 1830

. . . The gentleman insists that the states have no right to decide whether the constitution has been violated by acts of Congress or not,—but that the federal government is the exclusive judge of the extent of its own powers; and that in case of a violation of the constitution, however “deliberate, palpable and dangerous,” a state has no constitutional redress, except where the matter can be brought before the Supreme Court, whose decision must be final and conclusive on the subject. Having thus distinctly stated the points in dispute between the gentleman and myself, I proceed to examine them.

And here it will be necessary to go back to the origin of the federal government. It cannot be doubted, and is not denied, that before the formation of the constitution, each state was an independent sovereignty, possessing all the rights and powers appertaining to independent nations; nor can it be denied that, after the Constitution was formed, they remained equally sovereign and independent, as to all powers, not expressly delegated to the federal government. This would have been the case even if no positive provision to that effect had been inserted in that instrument. But to remove all doubt it is expressly declared, by the 10th article of the amendment of the Constitution, “that the powers not delegated to the states, by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.”. . .

The whole form and structure of the federal government, the opinions of the Framers of the Constitution, and the organization of the state governments, demonstrate that though the states have surrendered certain specific powers, they have not surrendered their sovereignty. . . .

No doubt can exist, that, before the states entered into the compact, they possessed the right to the fullest extent, of determining the limits of their own powers—it is incident to all sovereignty. Now, have they given away that right, or agreed to limit or restrict it in any respect? Assuredly not. They have agreed, that certain specific powers shall be exercised by the federal government; but the moment that government steps beyond the limits of its charter, the right of the states “to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits the authorities, rights, and liberties, appertaining to them,”[7] is as full and complete as it was before the Constitution was formed. It was plenary then, and never having been surrendered, must be plenary now. . . .

But the gentleman apprehends that this will “make the Union a rope of sand.” Sir, I have shown that it is a power indispensably necessary to the preservation of the constitutional rights of the states, and of the people. I now proceed to show that it is perfectly safe, and will practically have no effect but to keep the federal government within the limits of the Constitution, and prevent those unwarrantable assumptions of power, which cannot fail to impair the rights of the states, and finally destroy the Union itself. . . .

A state will be restrained by a sincere love of the Union. The people of the United States cherish a devotion to the Union, so pure, so ardent, that nothing short of intolerable oppression, can ever tempt them to do anything that may possibly endanger it. Sir, there exists, moreover, a deep and settled conviction of the benefits, which result from a close connection of all the states, for purposes of mutual protection and defense. This will co-operate with the feelings of patriotism to induce a state to avoid any measures calculated to endanger that connection. . . .

The gentleman has made an eloquent appeal to our hearts in favor of union. Sir, I cordially respond to that appeal. I will yield to no gentleman here in sincere attachment to the Union,—but it is a Union founded on the Constitution, and not such a Union as that gentleman would give us, that is dear to my heart. If this is to become one great “consolidated government,” swallowing up the rights of the states, and the liberties of the citizen, “riding and ruling over the plundered ploughman, and beggared yeomanry,”[8] the Union will not be worth preserving. Sir, it is because South Carolina loves the Union, and would preserve it forever, that she is opposing now, while there is hope, those usurpations of the federal government, which, once established, will, sooner or later, tear this Union into fragments. . . .

- 1. See the Missouri Compromise Act.

- 2. See Genesis 9:20–27. These verses recount the first occurrence of slavery. Noah grew a vineyard, got drunk on wine and lay naked. Ham, one of Noah’s sons, saw him uncovered, for which Noah cursed him by making Ham’s son, Canaan, a slave to Ham's brothers. This episode was used in nineteenth century America as a Biblical justification for slavery.

- 3. George Washington

- 4. Perhaps a quotation from a speech in Parliament in 1803 of Lord Castlereagh, Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry (1769–1822) during a debate over the conduct of British officials in India.

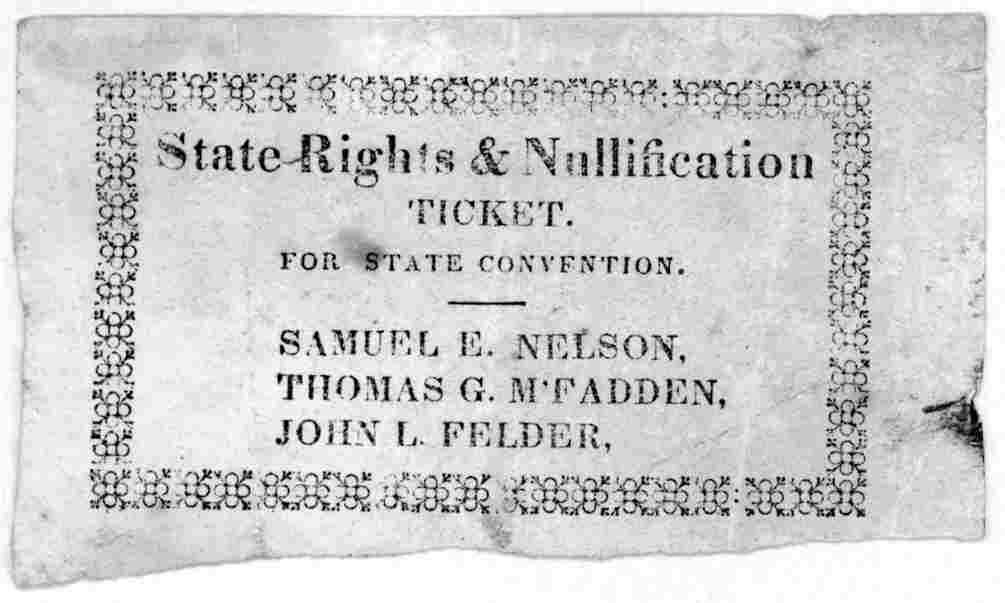

- 5. The idea that a state could nullify a federal law, associated with South Carolina, especially after the publication of John C. Calhoun’s South Carolina Exposition and Protest (1828) in response to the tariff passed in that year. Several state governments or courts, some in the north, had espoused the idea of nullification prior to 1828. For Calhoun, see the Speech on Abolition Petitions and the Speech on the Oregon Bill.

- 6. The Northwest Ordinance. The following states came from the territory north and west of the Ohio river: Ohio (1803), Indiana (1816), Illinois (1818), Michigan (1837), Wisconsin (1848) and Minnesota (1858).

- 7. Hayne quotes from the Virginia Resolution (1798), authored by Thomas Jefferson, to protest the Alien and Sedition Acts (1798). The Virginia Resolution asserted that when the federal government undertook the “deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of” powers not granted to it in the constitution, states had the right and duty to interpose their authority to prevent this evil.

- 8. Hayne quotes from Thomas Jefferson to William Branch Giles, December 26, 1825, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/letter-to-william-branch-giles/?_sft_document_author=thomas-jefferson.

On the Nullifying Doctrine

April 03, 1830

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.