No related resources

Introduction

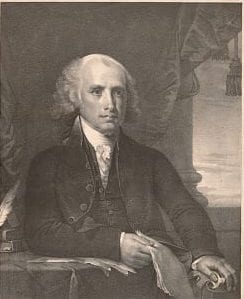

Tariffs raise the price of imported goods. When these goods are manufactures, the tariff benefits local manufacturers because they can sell their goods for a higher price. It harms consumers of manufactured goods because they must pay the higher price. In the United States, most manufacturers were in the northern states, and the consumers of manufactured goods were mostly in the southern and western states. In 1828, Congress passed a tariff to which many southerners objected. Some, particularly a group led by John C. Calhoun (1782–1850), responded to the tariff by contending that states could nullify federal laws. When advocates of nullification sought to draw support from the Virginia Resolutions of 1798, James Madison (1751–1836) wrote several letters and essays drawing a distinction between interposition and nullification. He repeatedly rejected any notion that arguments for interposition advanced in the Virginia Resolutions provided a foundation for the doctrine of nullification. In this letter to Edward Everett (1794–1865), Madison set out several reasons why he considered nullification to be unsupported by the Constitution and inconsistent with arguments advanced in the Virginia Resolutions.

Source: “James Madison to [Edward Everett], 28 August 1830,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/99-02-02-2138.

I have duly received your letter in which you refer to the “nullifying doctrine” advocated, as a constitutional right, by some of our distinguished fellow citizens; and to the proceedings of the Virginia Legislature in [17]98 & 99, as appealed to in behalf of that doctrine; and you express a wish for my ideas on those subjects.

I am aware of the delicacy of the task in some respects, and the difficulty in every respect of doing full justice to it. But having in more than one instance complied with a like request from other friendly quarters, I do not decline a sketch of the views which I have been led to take of the doctrine in question, as well as some others connected with them; and of the grounds from which it appears that the proceedings of Virginia have been misconceived by those who have appealed to them. In order to understand the true character of the Constitution of the United States, the error, not uncommon, must be avoided, of viewing it through the medium either of a consolidated government or of a confederated government, whilst it is neither the one nor the other; but a mixture of both. And having in no model, the similitudes and analogies applicable to other systems of government, it must more than any other be its own interpreter according to its text and the facts of the case....

Between these different constitutional governments, the one operating in all the states, the others operating separately in each, with the aggregate powers of government divided between them, it could not escape attention, that controversies would arise concerning the boundaries of jurisdiction; and that some provision ought to be made for such occurrences. A political system that does not provide for a peaceable and authoritative termination of occurring controversies would not be more than the shadow of a government; the object and end of a real government being the substitution of law and order for uncertainty confusion and violence.

That to have left a final decision, in such cases, to each of the states, then thirteen, and already twenty-four, could not fail to make the Constitution and laws of the United States different in different states, was obvious; and not less obvious, that this diversity of independent decisions must altogether distract the government of the Union, and speedily put an end to the Union itself. A uniform authority of the laws is in itself a vital principle. Some of the most important laws could not be partially executed. They must be executed in all the states or they could be duly executed in none. An impost or an excise, for example, if not in force in some states, would be defeated in others. It is well known that this was among the lessons of experience which had a primary influence in bringing about the existing Constitution. A loss of its general authority would moreover revive the exasperating questions between the states holding ports for foreign commerce and the adjoining states without them; to which are now added, all the inland states, necessarily carrying on their foreign commerce thro’ other states.

To have made the decisions under the authority of the individual states, co-ordinate, in all cases, with decisions under the authority of the United States, would unavoidably produce collisions incompatible with the peace of society, and with that regular and efficient administration which is of the essence of free governments. Scenes could not be avoided, in which a ministerial officer of the United States and the correspondent officer of an individual state would have rencounters1 in executing conflicting decrees; the result of which would depend on the comparative force of the local posse2 attending them; and that, a casualty depending on the political opinions and party feelings in different states.

To have referred every clashing decision, under the two authorities, for a final decision to the states as parties to the Constitution would be attended with delays, with inconveniences, and with expenses, amounting to a prohibition of the expedient; not to mention its tendency to impair the salutary veneration for a system requiring such frequent interpositions, nor the delicate questions which might present themselves as to the form of stating the appeal, and as to the quorum for deciding it.

To have trusted to negotiation for adjusting disputes between the government of the United States and the state governments, as between independent and separate sovereignties, would have lost sight altogether of a Constitution and government for the Union; and opened a direct road from a failure of that resort, to the ultima ratio3 between nations wholly independent of and alien to each other. If the idea had its origin in the process of adjustment, between separate branches of the same government, the analogy entirely fails. In the case of disputes between independent parts of the same government, neither part being able to consummate its will, nor the government to proceed without a concurrence of the parts, necessity brings about an accommodation. In disputes between a state government and the government of the United States, the case is practically as well as theoretically different; each party possessing all the departments of an organized government, legislative, executive, and judiciary; and having each, a physical force to support its pretensions. Although the issue of negotiation might sometimes avoid this extremity, how often would it happen among so many states, that an unaccommodating spirit in some would render that resource unavailing? A contrary supposition would not accord with a knowledge of human nature or the evidence of our own political history.

The Constitution not relying on any of the preceding modifications, for its safe and successful operation, has expressly declared, on one hand 1. “that the Constitution and the laws made in pursuance thereof and all treaties made under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; 2. that the judges of every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution and laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding;4 3. that the judicial power of the United States shall extend to all cases in law and equity arising under the Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made under their authority etc.”5

On the other hand, as a security of the rights and powers of the states, in their individual capacities, against an undue preponderance of the powers granted to the government over them in their united capacity, the Constitution has relied on 1. the responsibility of the senators and representatives in the legislature of the United States to the legislatures and people of the states; 2. the responsibility of the president to the people of the United States; and 3. the liability of the executive and judiciary functionaries of the United States to impeachment by the representatives of the people of the states, in one branch of the legislature of the United States, and trial by the representatives of the states, in the other branch: the state functionaries, legislative, executive, and judiciary, being at the same time, in their appointment and responsibility, altogether independent of the agency or authority of the United States....

Should the provisions of the Constitution as here reviewed, be found not to secure the government and rights of the states against usurpations and abuses on the part of the United States, the final resort within the purview of the Constitution, lies in an amendment of the Constitution according to a process applicable by the states.

And in the event of a failure of every constitutional resort, and an accumulation of usurpations and abuses, rendering passive obedience and nonresistance a greater evil than resistance and revolution, there can remain but one resort, the last of all; an appeal from the cancelled obligations of the constitutional compact, to original rights and the law of self-preservation. This is the ultima ratio under all governments, whether consolidated, confederated, or a compound of both; and it cannot be doubted that a single member of the Union, in the extremity supposed, but in that only, would have a right, as an extra and ultra-constitutional right, to make the appeal....

In favor of the nullifying claim for the states, individually, it appears as you observe that the proceedings of the legislature of Virginia in 98 & 99 against the Alien and Sedition Acts are much dwelt upon.

It may often happen, as experience proves, that erroneous constructions not anticipated, may not be sufficiently guarded against, in the language used; and it is due to the distinguished individuals who have misconceived the intention of those proceedings, to suppose that the meaning of the legislature, though well comprehended at the time, may not now be obvious to those unacquainted with the contemporary indications and impressions.

But it is believed that by keeping in view the distinction between the governments of the states, and the states in the sense in which they were parties to the Constitution; between the rights of the parties, in their concurrent, and in their individual capacities; between the several modes and objects of interposition against the abuses of power; and especially between interpositions within the purview of the Constitution, and interpositions appealing from the Constitution to the rights of nature paramount to all constitutions; with these distinctions kept in view, and an attention, always of explanatory use, to the views and arguments which were combated, a confidence is felt, that the Resolutions of Virginia as vindicated in the Report on them, will be found entitled to an exposition, showing a consistency in their parts, and an inconsistency of the whole with the doctrine under consideration.

That the legislature could not have intended to sanction such a doctrine is to be inferred from the debates in the House of Delegates, and from the address of the two houses, to their constituents, on the subject of the Resolutions. The tenor of the debates, which were ably conducted and are understood to have been revised for the press by most if not all of the speakers, discloses no reference whatever to a constitutional right in an individual state, to arrest by force the operation of a law of the United States. Concert among the states for redress against the Alien and Sedition laws, as acts of usurped power, was a leading sentiment; and the attainment of a concert, the immediate object of the course adopted by the legislature, which was that of inviting the other states “to concur, in declaring the acts to be unconstitutional, and to cooperate by the necessary and proper measures, in maintaining unimpaired the authorities rights and liberties reserved to the states respectively and to the people.”6 That by the necessary and proper measures to be concurrently and cooperatively taken were meant measures known to the Constitution, particularly the ordinary control of the people and legislatures of the states, over the government of the United States, cannot be doubted; and the interposition of this control, as the event showed, was equal to the occasion.

It is worthy of remark, and explanatory of the intentions of the legislature, that the words “not law, but utterly null, void, and of no force or effect” which had followed, in one of the Resolutions, the word “unconstitutional,” were struck out by common consent. Tho’ the words were in fact but synonymous with “unconstitutional”; yet to guard against a misunderstanding of this phrase as more than declaratory of opinion, the word unconstitutional, alone was retained, as not liable to that danger.

The published address of the legislature to the people their constituents affords another conclusive evidence of its views. The address warns them against the encroaching spirit of the general government, argues the unconstitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Acts, points to other instances in which the constitutional limits had been overleaped; dwells on the dangerous mode of deriving power by implication; and in general presses the necessity of watching over the consolidating tendency of the federal policy. But nothing is said that can be understood to look to means of maintaining the rights of the states, beyond the regular ones, within the forms of the Constitution....

- 1. A chance meeting.

- 2. A posse or posse comitatus (Latin term meaning an enabled or armed escort) was a group deputized to assist a sheriff. In this instance, Madison was speaking more informally and saying that if federal and state authority were equal, the enforcement of conflicting decrees would depend on whether the state or federal official could muster the greater force.

- 3. A last resort, usually implying the use of force.

- 4. Article VI.

- 5. Article III, section 2.

- 6. Madison’s note: see the concluding Resolution of 1798.

Annual Message to Congress (1830)

December 6, 1830

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.