No related resources

Introduction

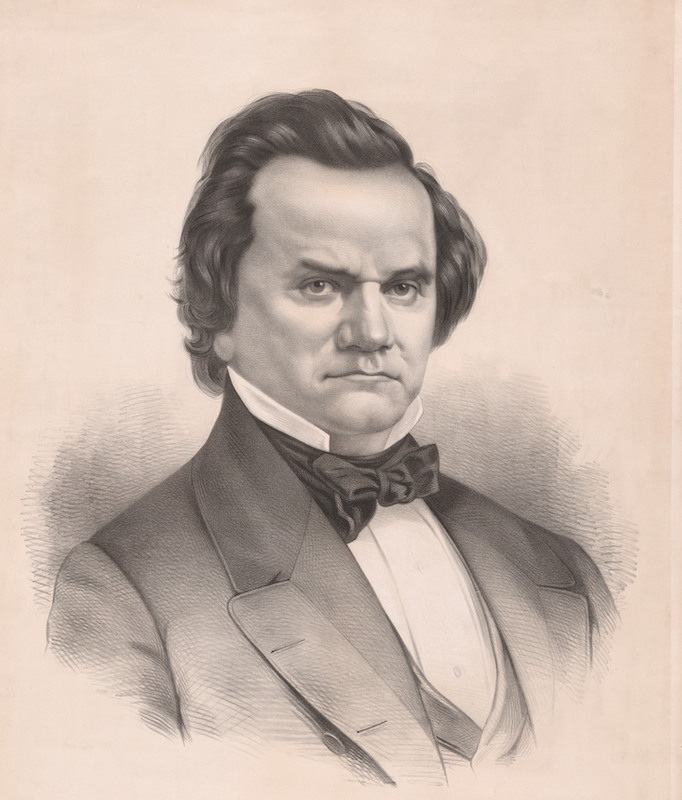

In 1858, slavery and the Dred Scott decision were central issues in the Illinois Senate race between incumbent senator Stephen Douglas (1813–1861) and challenger Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865). The two held a series of debates during the campaign. In one of them, Lincoln argued, as he had before, that Dred Scott was wrongly decided. He believed the decision was part of a “conspiracy to perpetuate and nationalize slavery,” and that the Court’s erroneous reasoning should not be considered binding.

In this response to Lincoln’s attacks on Dred Scott and judicial supremacy, Douglas argued that under Article III of the Constitution the Court did have the authority “to pronounce judgment on the validity and constitutionality of an act of Congress.” If Lincoln disagreed with Dred Scott, Douglas said, he should seek a seat on the Court rather than trying to undermine the decision through political means. But he also mocked Lincoln’s intent to overturn Dred Scott by electing a president who would appoint judges opposed to the decision. Among his criticisms of this idea, Douglas noted that it would require the president to “catechise” prospective justices and force them to confess how they would rule on a reconsideration of Dred Scott (today, we call this a “litmus test”). Douglas argued that a court composed of such judges would lose the confidence of the American people.

Source: The Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. John Nicolay and John Hay (Harrogate, Tenn.: Lincoln Memorial University 1894), 132–154, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/msu.31293023047990.

. . . Mr. Lincoln’s. . . last point is, that he will wage a warfare upon the Supreme Court of the United States because of the Dred Scott decision. He takes occasion, in his speech made before the Republican Convention, in my absence, to arraign me, not only for having expressed my acquiescence in that decision, but to charge me with being a conspirator with that Court in devising that decision three years before Dred Scott ever thought of commencing a suit for his freedom. The object of his speech was to convey the idea to the people that the Court could not be trusted, that the late president could not be trusted, that the present one could not be trusted, and that Mr. Douglas could not be trusted; that they were all conspirators in bringing about that corrupt decision, to which Mr. Lincoln is determined he will never yield a willing obedience.1

He makes two points upon the Dred Scott decision. The first is that he objects to it because the Court decided that negroes descended of slave parents are not citizens of the United States; and secondly, because they have decided that the act of Congress, passed 8th of March, 1820,2 prohibiting slavery in all of the territories north of 36°30´, was unconstitutional and void, and hence did not have effect in emancipating a slave brought into that territory. And he will not submit to that decision. He says that he will not fight the judges or the United States marshals in order to liberate Dred Scott, but that he will not respect that decision, as a rule of law binding on this country, in the future. Why not? Because, he says, it is unjust. How is he going to remedy it? Why, he says he is going to reverse it. How? He is going to take an appeal. To whom is he going to appeal? The Constitution of the United States provides that the Supreme Court is the ultimate tribunal, the highest judicial tribunal on earth; and Mr. Lincoln is going to appeal from that. To whom? I know he appealed to the Republican State Convention of Illinois, and I believe that convention reversed the decision; but I am not aware that they have yet carried it into effect. How are they going to make that reversal effectual? Why, Mr. Lincoln tells us in his late Chicago speech. He explains it as clear as light. He says to the people of Illinois that if you elect him to the Senate he will introduce a bill to reenact the law which the Court pronounced unconstitutional. [Shouts of laughter, and voices, “Spot the law.”] Yes, he is going to spot the law.3 The court pronounces that law, prohibiting slavery, unconstitutional and void, and Mr. Lincoln is going to pass an act reversing that decision and making it valid. I never heard before of an appeal being taken from the Supreme Court to the Congress of the United States to reverse its decision. I have heard of appeals being taken from Congress to the Supreme Court to declare a statute void. That has been done from the earliest days of Chief Justice Marshall, down to the present time.4

The Supreme Court of Illinois does not hesitate to pronounce an act of the legislature void, as being repugnant to the Constitution, and the Supreme Court of the United States is vested by the Constitution with that very power. The Constitution says that the judicial power of the United States shall be vested in the Supreme Court, and such inferior courts as Congress shall, from time to time, ordain and establish. Hence it is the province and duty of the Supreme Court to pronounce judgment on the validity and constitutionality of an act of Congress. In this case they have done so, and Mr. Lincoln will not submit to it, and he is going to reverse it by another act of Congress of the same tenor. My opinion is that Mr. Lincoln ought to be on the Supreme bench himself, when the Republicans get into power, if that kind of law knowledge qualifies a man for the bench. But Mr. Lincoln intimates that there is another mode by which he can reverse the Dred Scott decision. How is that? Why, he is going to appeal to the people to elect a president who will appoint judges who will reverse the Dred Scott decision. Well, let us see how that is going to be done. First, he has to carry on his sectional organization, a party confined to the free states, making war upon the slaveholding states until he gets a Republican president elected. [“He never will, sir.”] I do not believe he ever will. But suppose he should; when that Republican president shall have taken his seat (Mr. Seward, for instance), will he then proceed to appoint judges? No! he will have to wait until the present judges die before he can do that, and perhaps his four years would be out before a majority of these judges found it agreeable to die; and it is very possible, too, that Mr. Lincoln’s senatorial term would expire before these judges would be accommodating enough to die. If it should so happen I do not see a very great prospect for Mr. Lincoln to reverse the Dred Scott decision. But suppose they should die, then how are the new judges to be appointed? Why, the Republican president is to call upon the candidates and catechise them, and ask them, “How will you decide this case if I appoint you judge?” Suppose, for instance, Mr. Lincoln to be a candidate for a vacancy on the Supreme bench to fill Chief Justice Taney’s place and when he applied to Seward, the latter would say, “Mr. Lincoln, I cannot appoint you until I know how you will decide the Dred Scott case?” Mr. Lincoln tells him, and then asks him how he will decide Tom Jones’ case, and Bill Wilson’s case, and thus catechises the judge as to how he will decide any case which may arise before him. Suppose you get a Supreme Court composed of such judges, who have been appointed by a partisan president upon their giving pledges how they would decide a case before it arose—what confidence would you have in such a court?

Would not your Court be prostituted beneath the contempt of all mankind? What man would feel that his liberties were safe, his right of person or property was secure, if the Supreme bench, that august tribunal, the highest on earth, was brought down to that low, dirty pool wherein the judges are to give pledges in advance how they will decide all the questions which may be brought before them? It is a proposition to make that Court the corrupt, unscrupulous tool of a political party. But Mr. Lincoln cannot conscientiously submit, he thinks, to the decision of a court composed of a majority of Democrats. If he cannot, how can he expect us to have confidence in a court composed of a majority of Republicans, selected for the purpose of deciding against the Democracy, and in favor of the Republicans? The very proposition carries with it the demoralization and degradation destructive of the judicial department of the federal government.

I say to you, fellow citizens, that I have no warfare to make upon the Supreme Court because of the Dred Scott decision. I have no complaints to make against that Court, because of that decision. My private opinions on some points of the case may have been one way and on other points of the case another; in some things concurring with the Court and in others dissenting; but what have my private opinions in a question of law to do with the decision after it has been pronounced by the highest judicial tribunal known to the Constitution? You, sir [addressing the chairman of the meeting], as an eminent lawyer, have a right to entertain your opinions on any question that comes before the court and to appear before the tribunal and maintain them boldly and with tenacity until the final decision shall have been pronounced, and then, sir, whether you are sustained or overruled your duty as a lawyer and a citizen is to bow in deference to that decision. I intend to yield obedience to the decisions of the highest tribunals in the land in all cases whether their opinions are in conformity with my views as a lawyer or not. When we refuse to abide by judicial decisions what protection is there left for life and property? To whom shall you appeal? To mob law, to partisan caucuses, to town meetings, to revolution? Where is the remedy when you refuse obedience to the constituted authorities? I will not stop to inquire whether I agree or disagree with all the opinions expressed by Judge Taney or any other judge. It is enough for me to know that the decision has been made. It has been made by a tribunal appointed by the Constitution to make it; it was a point within their jurisdiction, and I am bound by it. . . .

- 1. Douglas referred to Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech, in which he accused Douglas, former president Franklin Pierce (1804–1869), Chief Justice Roger Taney (1777– 1864), and current president James Buchanan (1791–1868) of a conspiracy, including the Dred Scott decision, to make slavery legal nationwide.

- 2. Part of the Missouri Compromise.

- 3. A reference to Lincoln’s “Spot Resolutions.” As a congressman opposed to war with Mexico, Lincoln had proposed resolutions calling for President Polk to identify the spots on American soil where Mexican soldiers had spilled American blood. The claimed attack by Mexican forces was a cause of the war, according to Polk.

- 4. Marbury v. Madison and McCulloch v. Maryland.

Fragment on Slavery

August 1, 1858

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.