Introduction

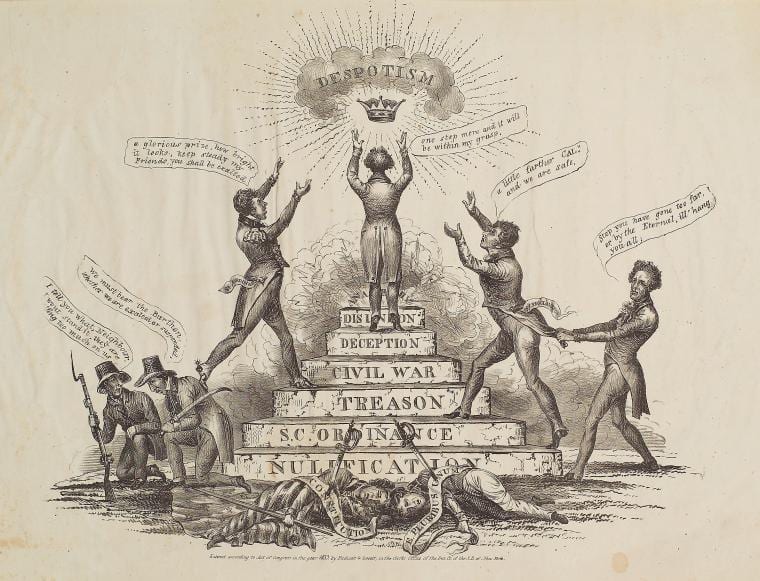

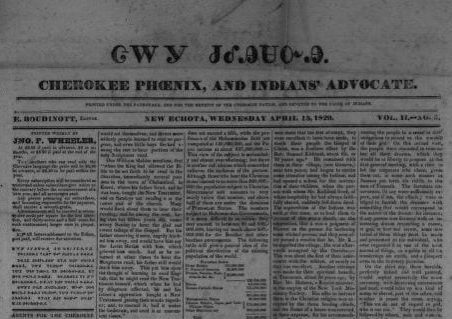

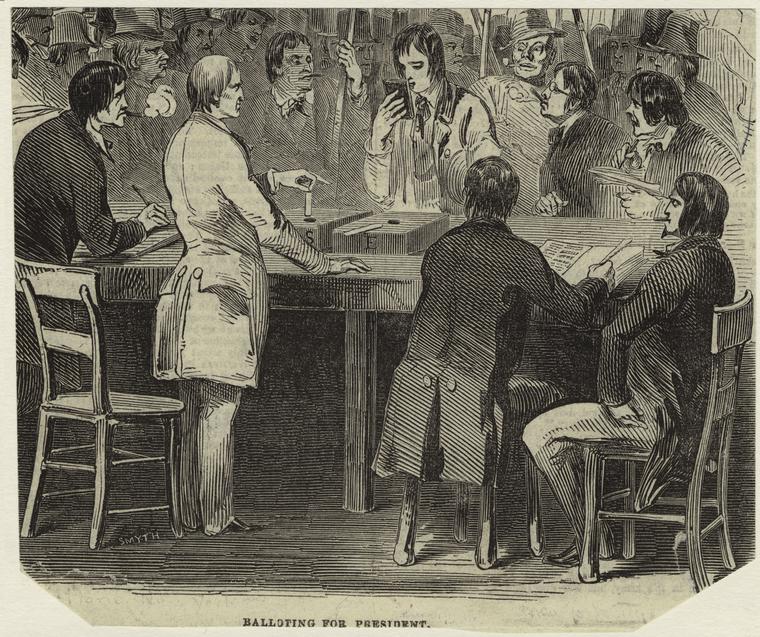

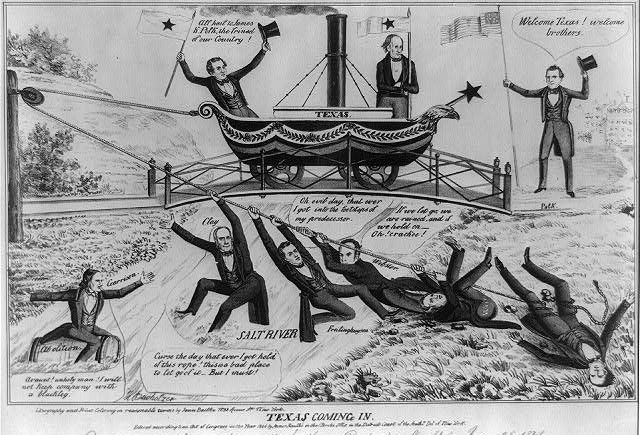

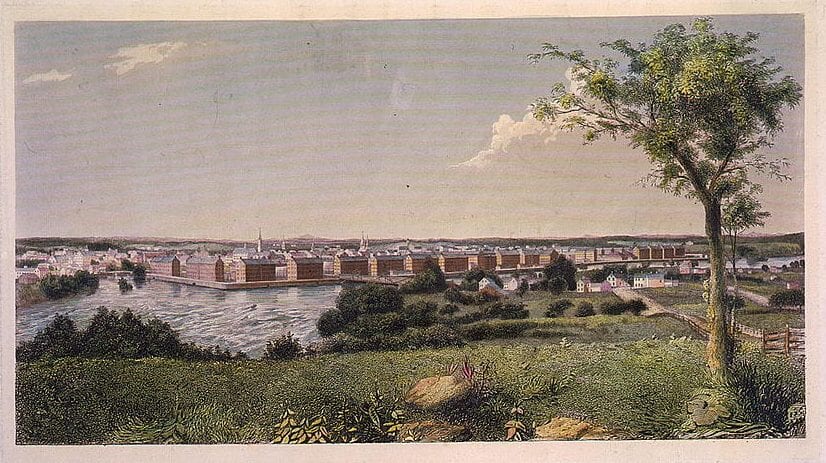

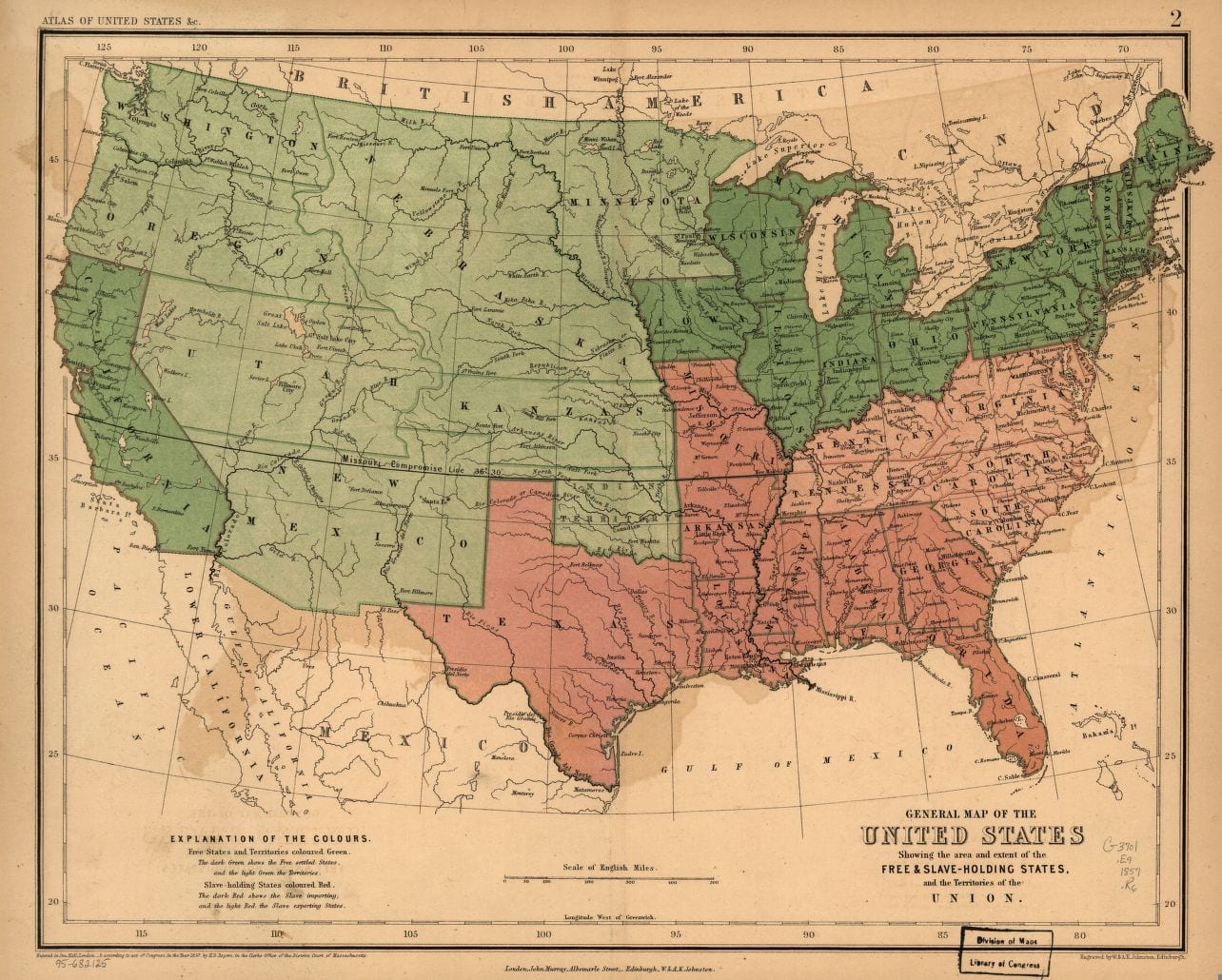

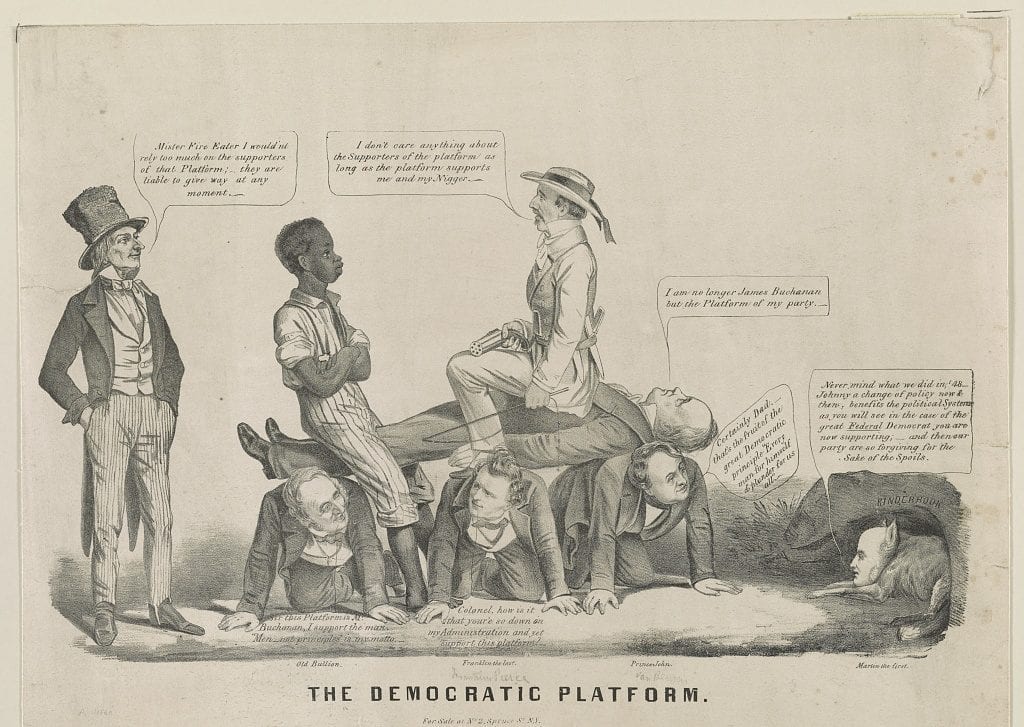

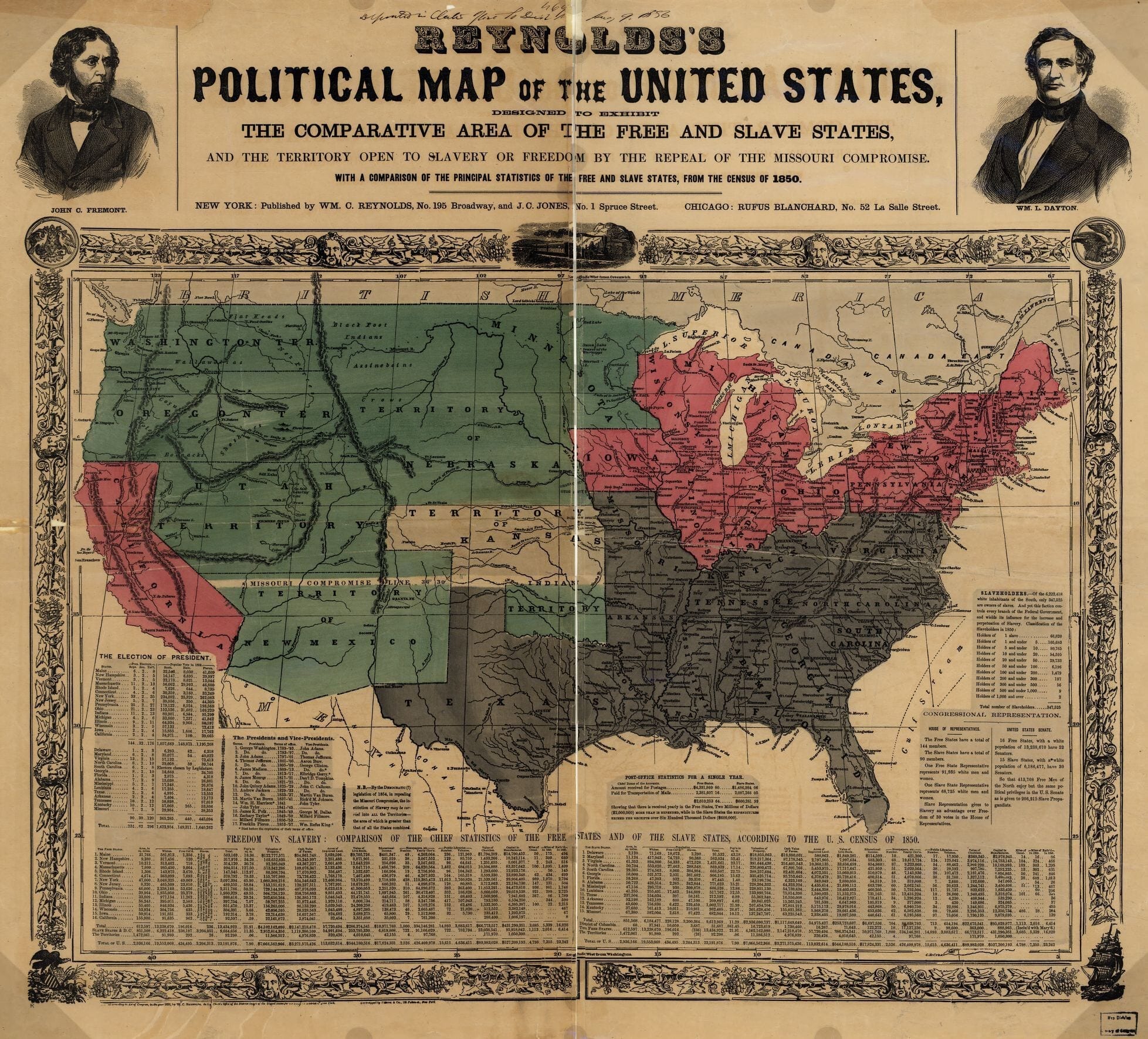

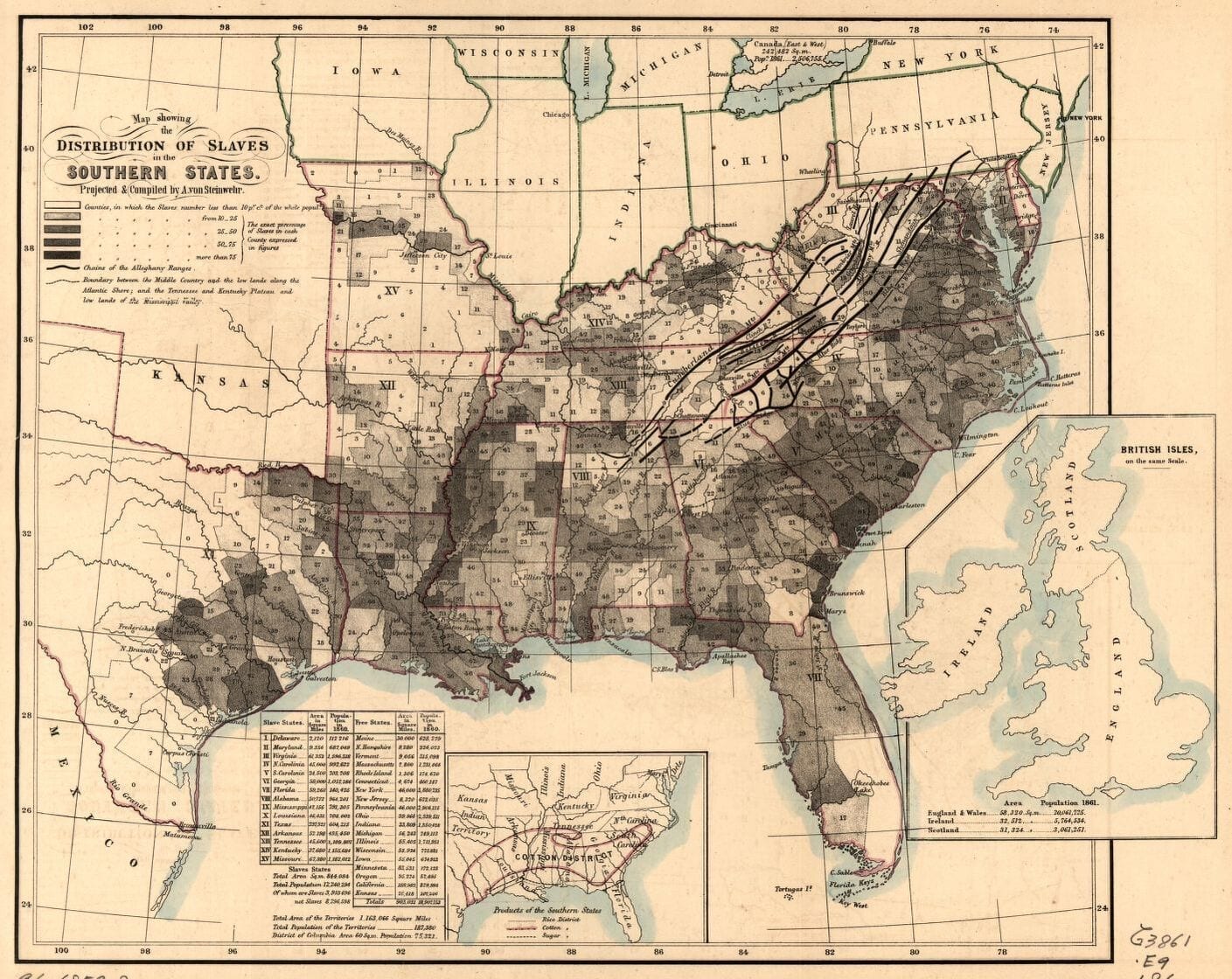

Chartering a National Bank for the United States was consistently a contentious issue in American politics prior to the Civil War. Although a private institution, the U.S. government owned 20 percent of the shares in the bank and was directly responsible for its supervision. Many Federalists—and later, Whigs—saw the National Bank as indispensable to the growth of the young nation. Southerners such as the Jeffersonian Republicans and Jacksonian Democrats were suspicious of the bank and its potential aristocratic tendencies, which they believed favored the interests of wealthy speculators, merchants, and other interests concentrated in the North.

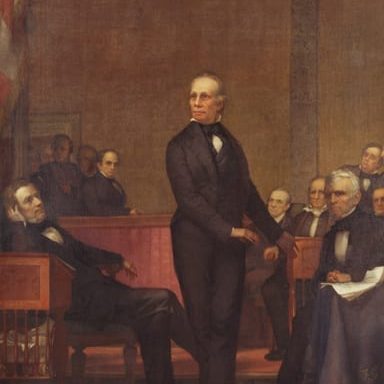

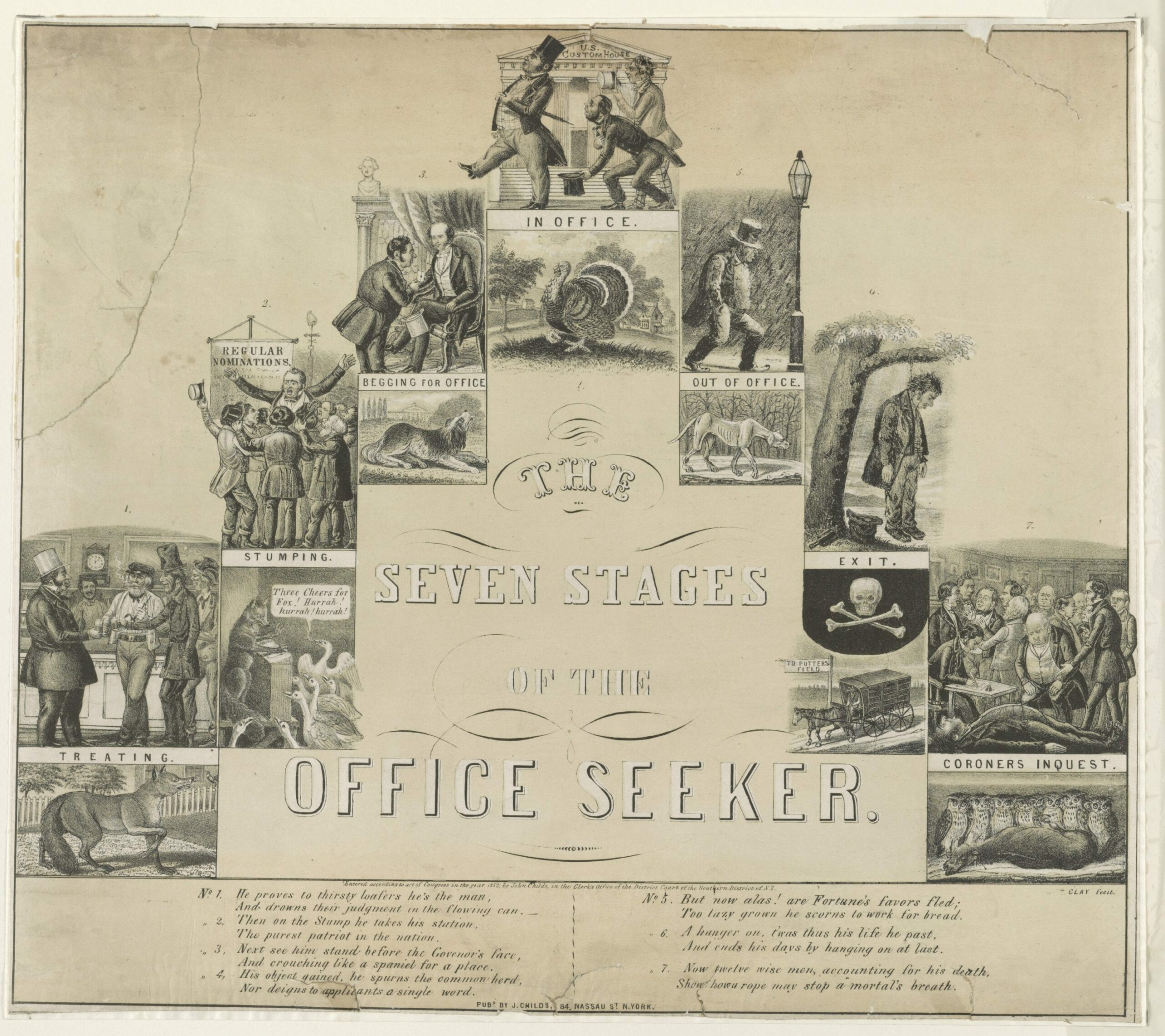

In 1841, rechartering the National Bank was again on Congress’s agenda. Henry Clay, a senator from Kentucky, who had previously served as Speaker of the House of Representatives, now sought to push the charter through the Senate. Clay was met with significant opposition by Southern Democrats, especially the obstinate Thomas Benton of Missouri. Clay’s opponents sought to delay the rechartering by using the privilege of unlimited debate, prompting Clay to seek to change the rules to allow a majority in the Senate to end debate and pass legislation. Thus, for the first time, the question of the Senate’s rules and the relationship between majority rule and minority input was raised on the floor of the Senate.

Source: Congressional Globe, 27th Congress, 1st Session, vol. 10 (June 12, 1841, July 12, 1841, and July 15, 1841), pp. 45–48, 181–184, 203–205.

June 12, 1841

The following resolution, moved some days ago by Mr. Clay of Kentucky,[1] having been taken up for consideration:

Resolved, That when the Senate adjourn during the present session leaving a subject under discussion and undecided, the consideration of the subject shall be resumed at the next meeting of the Senate, immediately after the journal is read and petitions and reports are received, without waiting for the usual hour of one o’clock:[2]

Mr. BENTON[3] objected to the resolution, as going unnecessarily to change the rules of the Senate. . . . It showed a determination to dictate to the Senate its order of business and the duration of the session. If it was persisted in, he would at least demand the yeas and nays. . . .

Mr. CLAY. . . Next week, the Senate would have before it the subject of a bank of the United States, presented in the form of a bill of thirty or thirty-two sections; and, to allow ample time for its consideration, he should move to change the hour of meeting to ten o’clock in the morning. He hoped the discussion of this important subject, as well as that of the distribution of the public lands and the currency, would be prosecuted from day to day, without stopping, until these great measures were brought to a consummation . . . he had no idea of exhausting the time of the Senate by collateral discussions, having no connection whatever with the business for which Congress had been called together; a specimen of which they had had before them, both yesterday and today. They distracted the attention and wasted the energy of the Senate, and went to prevent it from accomplishing the important ends for which it had been summoned. . . .

Let us (said Mr. C.) do our duty, and our whole duty; and let us do it as rapidly as it can be done, consistently with due deliberation. . . . Let us meet early and sit late; let us finish the work that is expected from us, and then go home. In urging this, he meant nothing unkind or improper to gentlemen on the other side of the House. There existed, indeed, an unfortunate difference of opinion between them; but let their contests be contests of intellect only, and not of brutal physical force; in seeing who could sit out the other, or consume the most time in useless debate. Mr. C. when in a minority, had never consented to any struggles of this kind; and he should not, now that circumstances were changed. He was for battling it mind against mind; let the talent on both sides of the House be fully measured and put forth, and then let the vanquished party submit with dignity, and not descend to a mere physical struggle. . . .

Mr. BENTON . . .This attempt to execute the objects of the dominant party in a summary and compendious way was very odious. He supposed the remarks of the Senator as to contests of physical force referred to his having, the other day, spoken at a late hour in opposition to the repeal of the Independent Treasury; but he had a right to speak, and he meant to exercise it to the fullest extent. He meant to speak on the McLeod case[4] if they had to speak till the church bells should ring to-morrow. He was not to be cut off by “hopes not.” He had his rights, and would exercise them. . . .

Mr. BUCHANAN[5] thought the resolution unnecessary. There was a courtesy among the members of that body which rendered it always easy for gentlemen to accomplish their wishes as to the order of business. . . .

Mr. KING . . . [6] never had concurred in any attempt to defeat measures by mere delay; yet he insisted that it was the duty of the majority in every public body to allow the minority a full and fair opportunity of discussing every measure proposed; to deny this was a species of legislative tyranny, in which gentlemen were too apt to “feel power and forget right.” He could assure the honorable senator from Kentucky that he would gain nothing by a course of this kind; it would only excite a spirit which it was desirable on every account to keep down, but which would very naturally be roused by making men feel that they are under rules which empowered the majority to cut out from the mass of business any subject they might choose to select, and push it on, regardless of the rights and wishes of their opponents. . . .

Mr. CALHOUN. . . . [7] submitted to gentlemen whether it was fair thus to cut off their opponents from an opportunity of bringing out the expression of their opinions on every important subject—yet that would be the whole effect of the proposed resolution. . . . Very rarely was such a thing witnessed as the attempt to thwart a measure by the mere consumption of time, or by a resort to the technicality of rules . . . he considered that the contest at this session was to be a contest of the great principles of the old Federal party against those of the old Republican party,[8] and its result would decide which was to have the predominance in this country. For his own part he honestly believed that upon that result the salvation of the country hung suspended. If gentlemen desired to shorten debate by observing an unbroken silence, let them do so; but let them at least afford the other side some opportunity to speak. He saw no reason for this resolution that could be creditable to those who urged it. This House moved rapidly, the other slowly; and as to setting them examples, would they look to the Senate for patterns to follow? If they did, it would be vain, because they could not follow them. . . .

Mr. CLAY… did gentlemen really expect, after the expression of public opinion which had taken place from one end of this land to the other, that they were to stand here five or six days on a stretch discussing that which the people had already decided? To what good end? Would it change the opinion of a single man? Would it do anything but consume the public time? . . . The country expected them to act—the country felt—the country suffered—the country was agonized by this everlasting consumption of time without action. . . . What was the practice in the British Parliament? They would very often sit all night to finish a measure, although on a few very extraordinary occasions the debate was protracted for several days. But here we continue to talk from day to day, from week to week, from month to month, while nothing was done. . . .

Mr. CALHOUN . . . He denied that the people demanded from them action alone. They demanded that they should act wisely . . . . It might suit the views of politicians and speculators that Congress should come to speedy action, especially on one subject. But what opportunity was allowed for deliberation and discussion? . . . The attempt thus to cut off debate was a thing unprecedented in the Senate. . . .

Mr. CLAY of Kentucky . . . But did the gentlemen really imagine that, because as a minority they possessed certain rights, they had the right of controlling the business of Congress? Suppose one of them should introduce a resolution, for example, on the subject of prescription, and the Senate should be drawn off to debate on that subject, what a sadly ludicrous spectacle would they not present to the American people, debating for months this matter of proscription. Would a course like that obey the will and fulfill the expectations of the American people? The presentation of resolutions would not be prevented by this rule, save at times when an important subject was under discussion, and remained undecided. He hoped that gentlemen would not insist on going, at this called session, into general unrestricted legislation. . . .

July 12, 1841

[The question of rechartering the National Bank was again taken up in the Senate.]

Mr. CLAY. . . He could not help regarding the opposition to this bill as one eminently calculated to delay the public business, with no other object that he could see than that of protracting to the last moment the measures for which this session had been expressly called to give to the people. . . .

This was now the third week in which the Senate had been engaged in the discussion of this bill. . . .

Mr. CALHOUN said he understood it had been repeated for the second time that there could be no other motive or object entertained by the senators in the opposition, in making amendments and speeches on this bill, than to embarrass the majority by frivolous and vexatious delay. . . .

Did the senator from Kentucky mean to apply to the Senate the gag law passed in the other branch of Congress?[9] If he did, it was time he should know that he, (Mr. CALHOUN,) and his friends were ready to meet him on that point. . . .

Mr. CLAY. . . He did not doubt that the senators on the other side conceived they were following the path of duty, and acting conscientiously, according to the opinions they entertained, in trying to defeat the measure, or, if they could not do that, to render it as odious as possible in the eyes of the world, in order that it might ultimately fail . . . .With regard to the time to be thus consumed on this measure, and the others in contemplation—such as the distribution of the proceeds of the public lands—have not these subjects been discussed over and over, and what necessity can there be of making long speeches on them now? Was it not all a wasteful delay of public business? . . . Let those senators go into the country, and they will find the whole body of the people complaining of the delay and interruption of the national business, by their long speeches in Congress; and if they will be but admonished by the people, they will come back with a lesson to cut short their debating, and give their attention more to action than to words. Who ever heard that the people would be dissatisfied with the abridgement of speeches in Congress? He had never heard the shortness of speeches complained of. Indeed, he should not be surprised if the people would get up remonstrances against lengthy speeches in Congress . . . .

[H]e was ready at any moment to bring forward and support a measure which should give to the majority the control of the business of the Senate of the United States. Let them denounce it as much as they pleased in advance; unmoved by any of their denunciations and threats, standing firm in the support of the interests which he believed the country demands, for one, he was ready for the adoption of a rule which would place the business of the Senate under the control of a majority of the Senate.

Mr. CALHOUN said there was no doubt of the senator’s predilection for a gag law. Let him bring on that measure as soon as ever he pleases . . . . .

Who consumed the time of last Congress in long speeches, vexatious and frivolous attempts to embarrass and thwart the business of the country, and useless opposition, tending to no end but that out of doors, the presidential election?[10] Who but the senator and his party, then in the minority? But now, when they are in the majority, and the most important measures ever pressed forward together in one session, he is the first to threaten a gag law, to choke off the debate, and deprive the minority even of the poor privilege of entering their protest. . . .

July 15, 1841

Mr. CLAY had one word to say on the subject of time. When at the early part of the session he had urged upon the Senate the necessity of action, and the example this grave body ought to show of despatch in the public business, he was met by the opposition with the cry of what is the use of such hurry; the other branch of Congress would be so far behind that it never could catch up. The cry was, “Why precipitate business? there is plenty of time for discussion-go on as we may, we shall be in advance of the House.” Now what was the fact? They were absolutely behind the House; the land bill, this bill, and others, had been passed by that body; and with all those important measures before them, taking up their time, it was asked why they had not brought it up earlier. . . . The reason was obvious. The majority there is for action, and has secured it. Some change was called for in this chamber. The truth is, that the minority here control the action of the Senate, and cause all the delay of the public business. They obstruct the majority in the despatch of all business of importance to the country, and particularly those measures which the majority is bound to give to the country without further delay. Did not this reduce the majority to the necessity of adopting some measure which would place the control of the business of the session in their hands? It was impossible to do without it; it must be resorted to. . . .

Mr. CALHOUN . . . The senator from Kentucky tells the Senate the other House has got before it. How has the other House got before the Senate? By a despotic exercise of the power of a majority. By destroying the liberties of the people in gagging their representatives. By preventing the minority from the free exercise of its right of remonstrance. This is the way the House has get before the Senate. And now there was too much evidence to doubt that the Senate was to be made to keep up with the House by the same means. . . .

Mr. CLAY . . . [W]ould have the senator to know that he would resort to the Constitution and act on the rights insured in it to the majority, by passing a measure that would insure the control of the business of the Senate to the majority. . . . It was the means of controlling the business, abridging long and unnecessary speeches, and would everywhere be hailed as one of the greatest improvement of the age. He thought it would be necessary to resort to similar means or some other, to give the majority a control of the business in the Senate. Look at the facts in this case. Here already three weeks and a half had been spent in amendment after amendment to this bill, being discussed and debated at as full length as if the whole bill was on its final passage. Yet if a proposition is urged to confine debate to the merits or demerits of each amendment, there is an outcry made about abridging the liberty of speech. Was such a course as that adopted on the other side proper? Was it such as would be tolerated by the American people? Did senators on the other side think that the people would complain that speeches were cut off which would prevent the public business from being carried on? No such thing; but they think they know the people. Now, he knew the people too, and he knew they were not going to complain about the abridgment of long speeches in Congress. They want their business to be done-they want action, and not so much talk about it. . . .

Mr. KING said the senator complained of three weeks and a half having been lost in amending his bill. Was not the senator aware that it was himself and his friends had consumed most of that time? But now that the minority had to take it up, the Senate is told there must be a gag law. Did he understand that it was the intention of the senator to introduce that measure?

Mr. CLAY. I will, sir; I will.

Mr. KING. I tell the senator, then, that he may make his arrangements at his boarding house for the winter. . . .

He (Mr. KING) was truly sorry to see the honorable senator so far forgetting what is due to the Senate as to talk of coercing it by any possible abridgment of its free action. The freedom of debate had never yet been abridged in that body since the foundation of this government. . . .

Mr. BENTON. . . . Senators have a constitutional right to speak; and while they speak to the subject before the House, there is no power anywhere to stop them. It is a constitutional right. When a member departs from the question, he is to be stopped; it is the duty of the chair—your duty, Mr. President, to stop him and it is the duty of the Senate to sustain you in the discharge of this duty. We have rules for conducting the debates, and these rules only require to be enforced in order to make debates decent and instructive in their import, and brief and reasonable in their duration. . . .

The opinion of the people is invoked-they are said to be opposed to long speeches, and in favor of action. But, do they want action without deliberation, without consideration, without knowing what we are doing? Do they want bills without amendments-without examination of details-without a knowledge of their effect and operation when they are passed? Certainly the people wish no such thing. They want nothing which will not bear discussion. The people are in favor of discussion, and never read our debates with more avidity than at this ominous and critical extraordinary session. But I can well conceive of those who are against those debates, and want them stifled. Old sedition law Federalism is against them. . . .

The previous question, and the old sedition law, are measure of the same character, and children of the same parents, and intended for the same purposes.[11] They are to hide light-to enable those in power to work in darkness. . . .

Sir, when the previous question shall be brought into this chamber-when it shall be applied to our bills in our quasi committee—I am ready to see my legislative life terminated. . . .

Mr. Calhoun . . . would tell the senator that the minority had rights under the Constitution which they meant to exercise, and let the senator try when he pleased to abridge those rights, he would find it no easy job. . . . He would give the senator from Kentucky notice to bring on his gag measure as soon as he pleased. He would find it no such easy matter as he seemed to think.

[The threats from Calhoun and King were prescient: Clay eventually relented on his motion to change the Senate’s rules, but he got his vote on July 28, when the Bank Bill passed the Senate.]

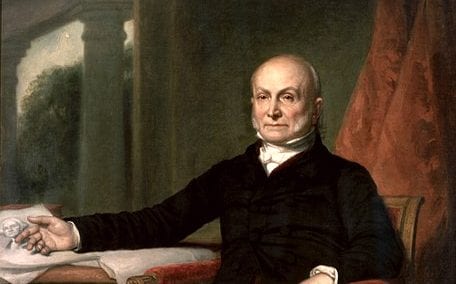

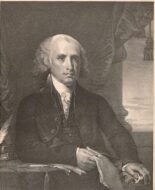

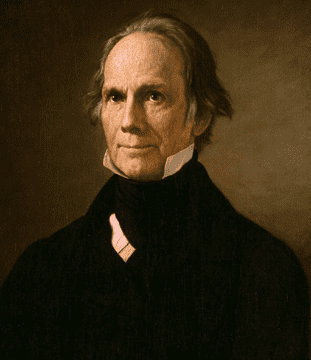

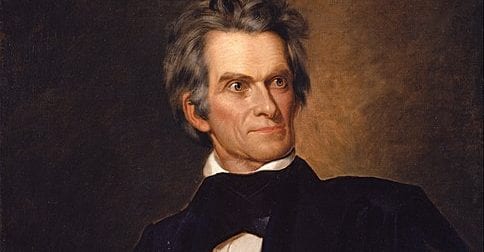

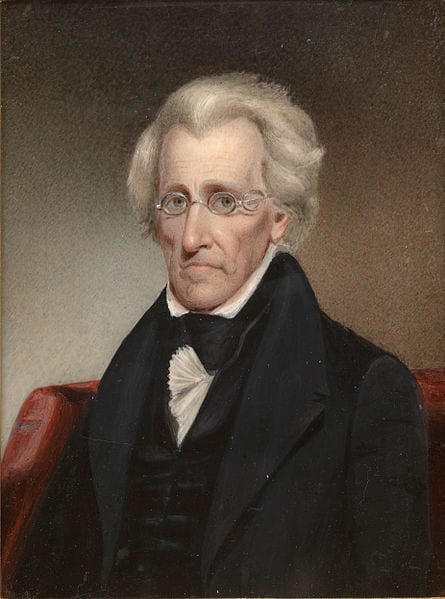

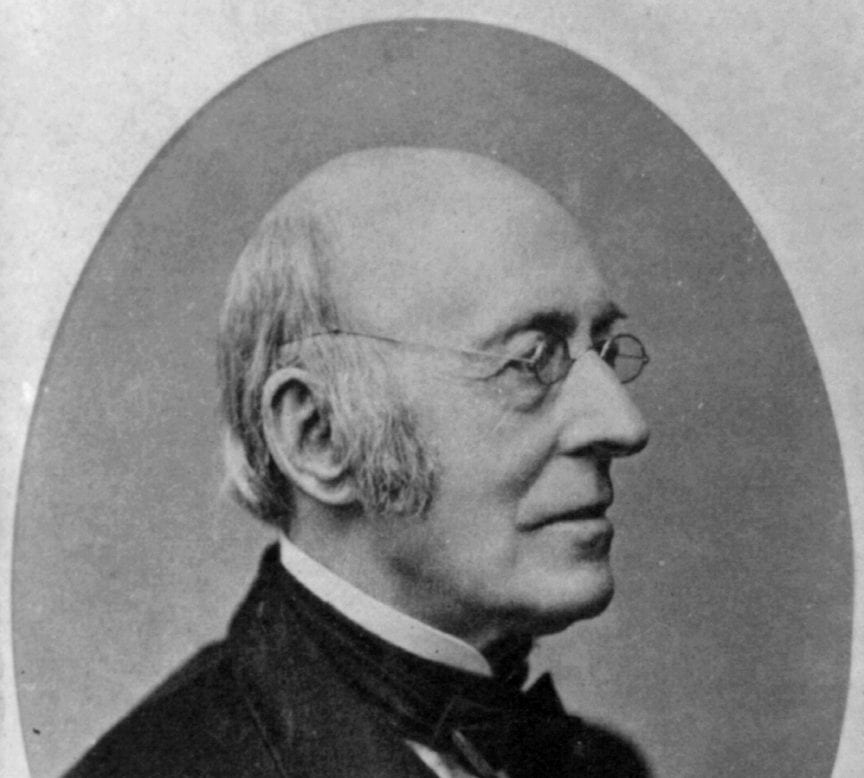

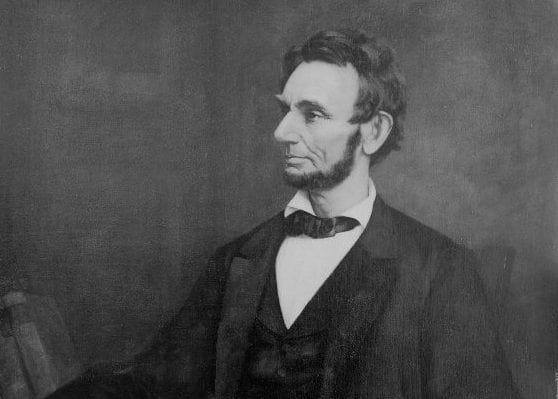

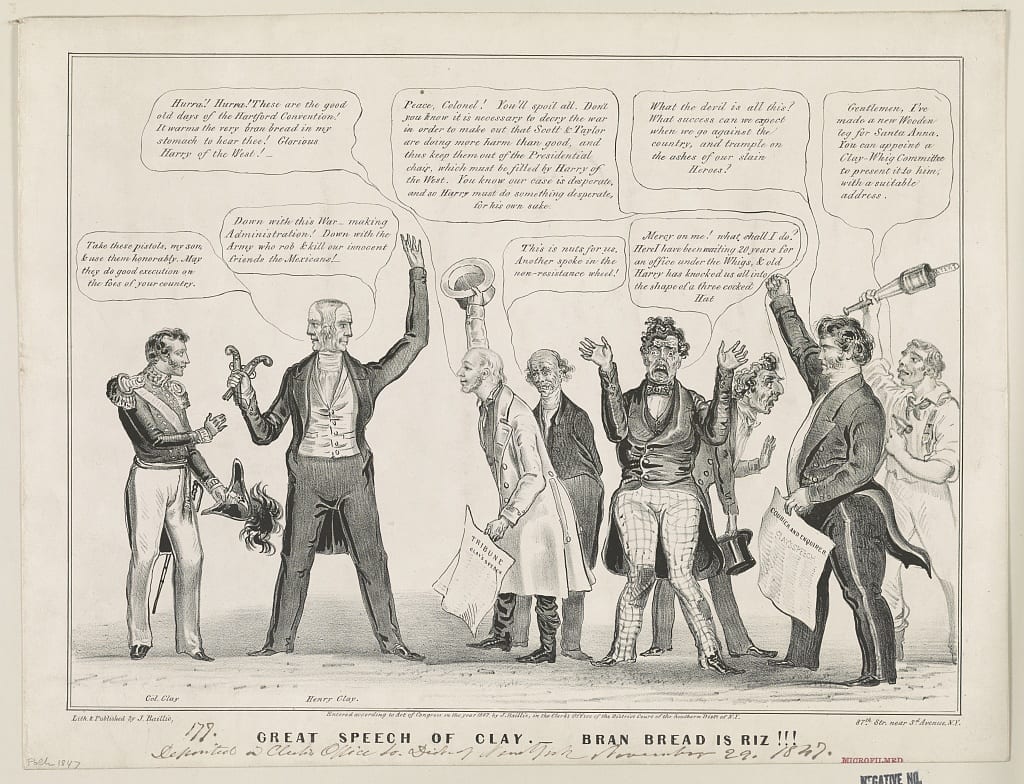

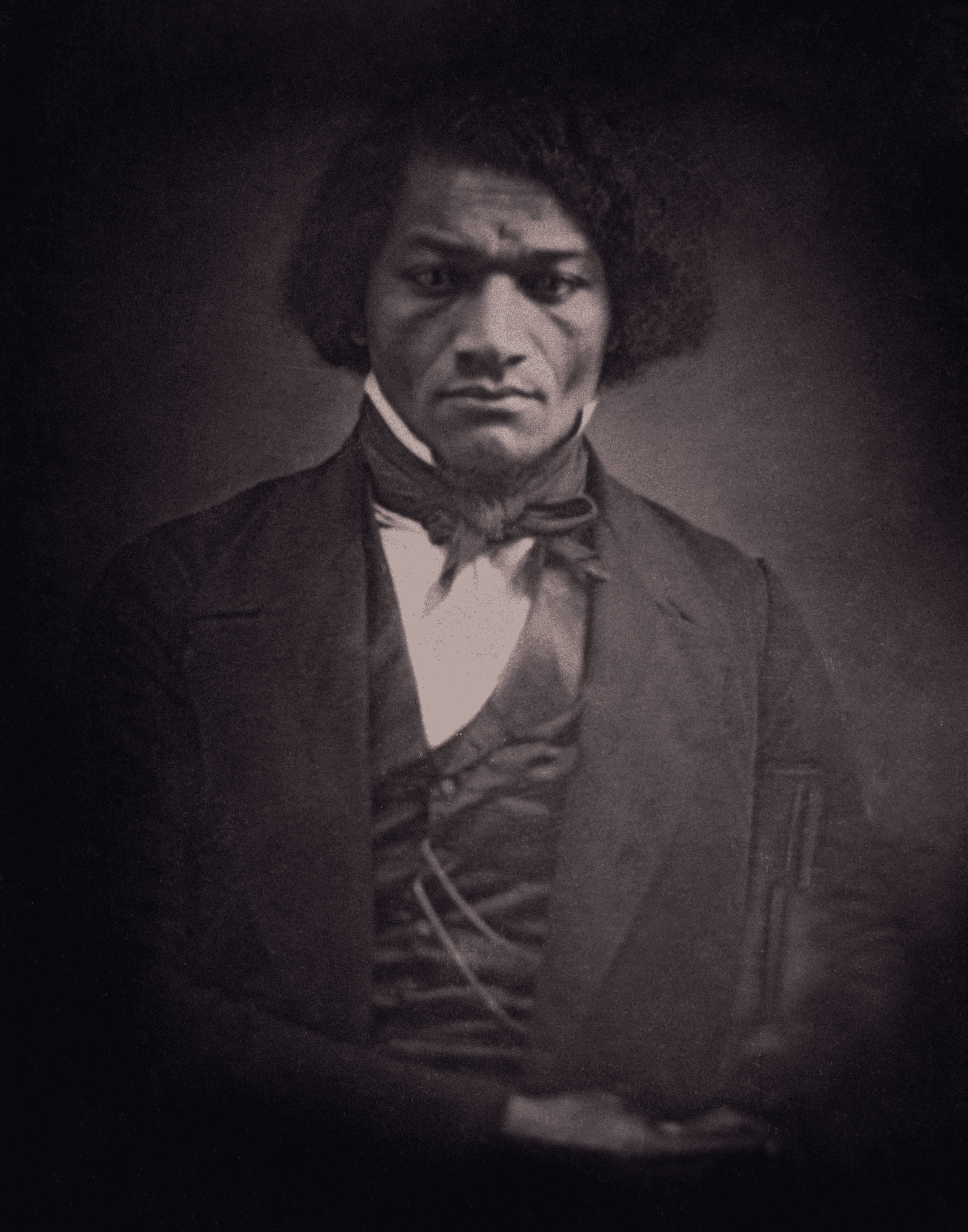

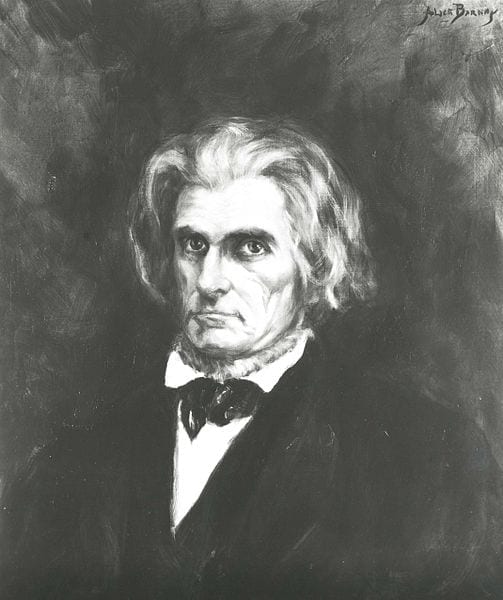

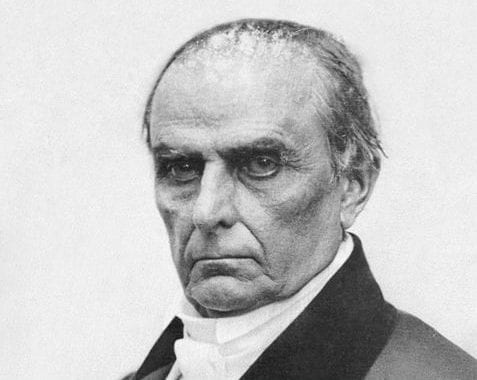

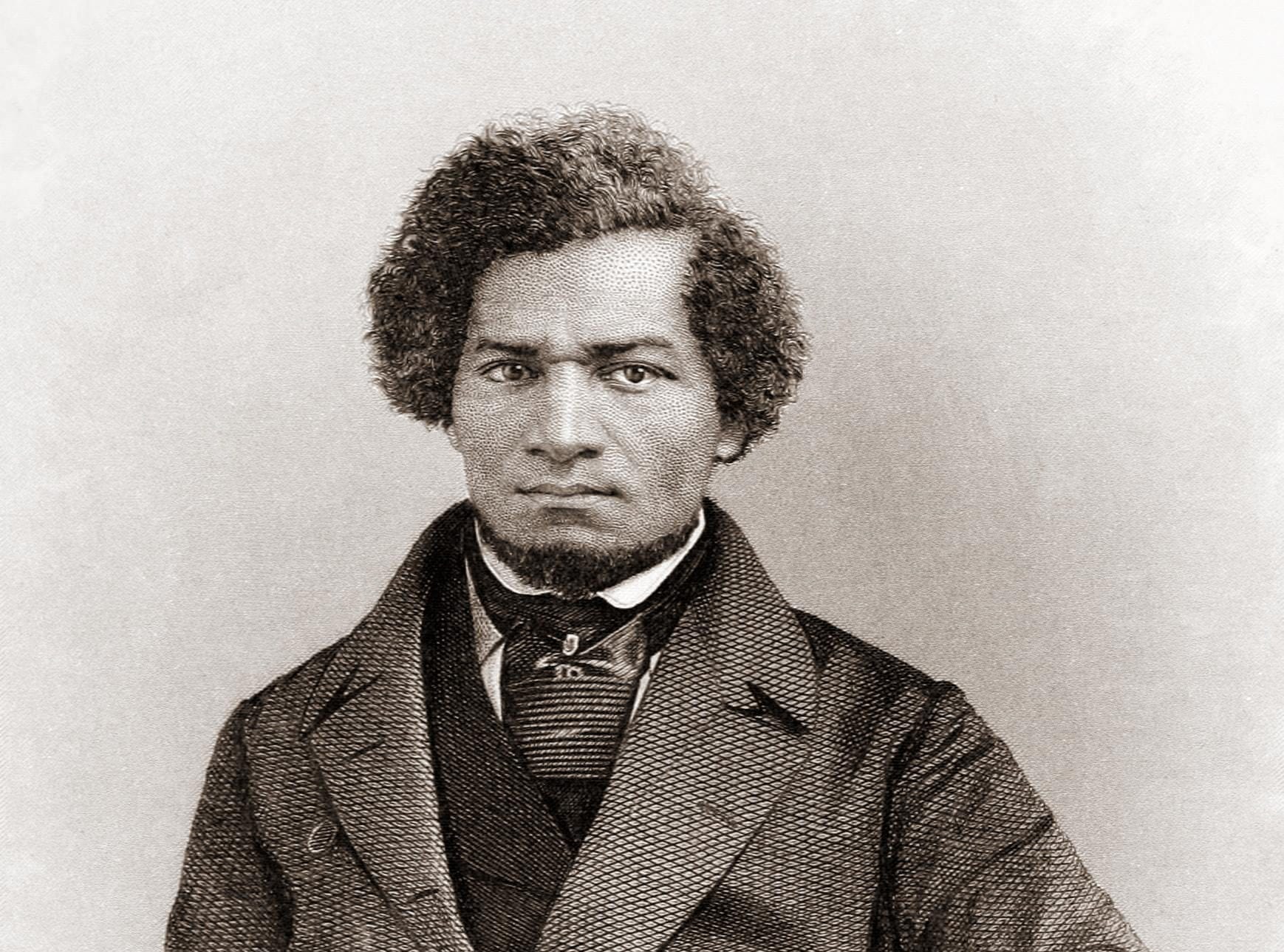

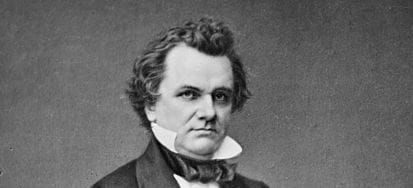

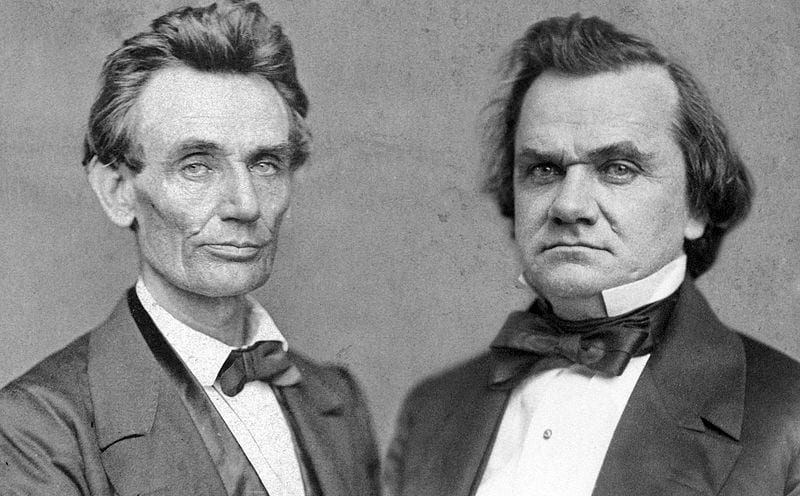

- 1. Henry Clay (1777–1852) was a senator from Kentucky, former Speaker of the House of Representatives, and presidential candidate. He is widely regarded as one of the great statesmen in early American history, part of the “Immortal Trio” of great pre-Civil War senators (with Daniel Webster and John Calhoun) and is sometimes called the “Great Compromiser” due to his role in forging various compromises on the issue of slavery.

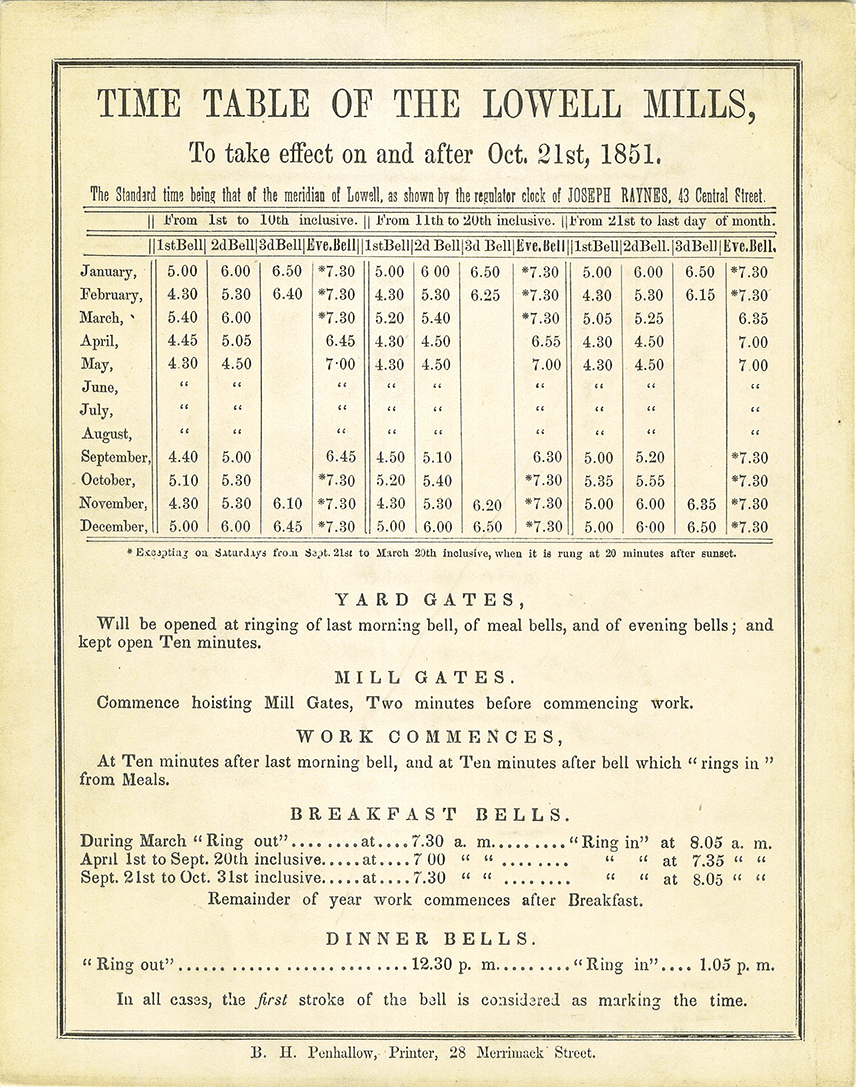

- 2. During this time, business on the Senate floor was reserved for afternoons, with none being conducted before 1 p.m. This allowed senators to attend committee meetings and to other duties before the afternoon session.

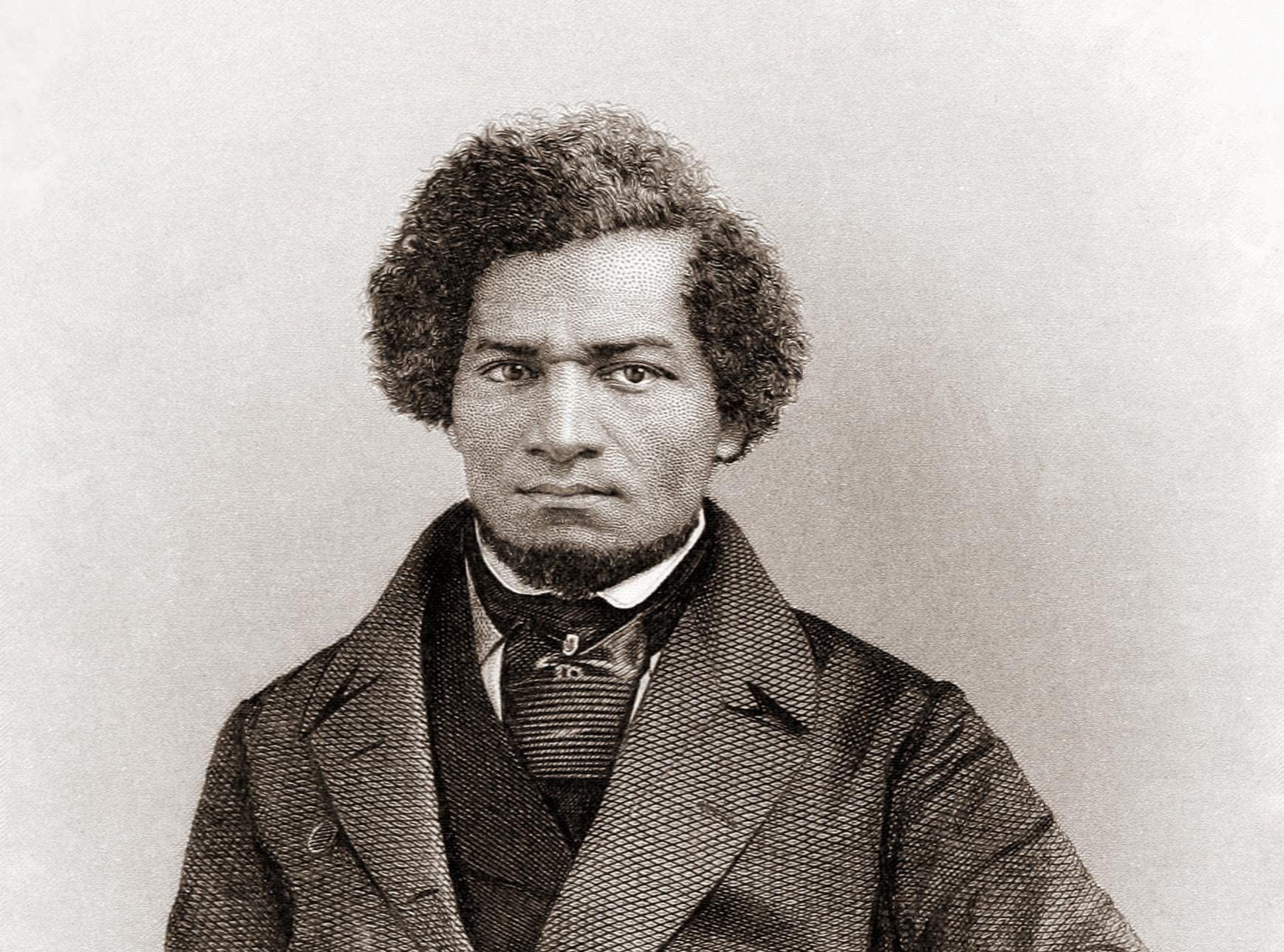

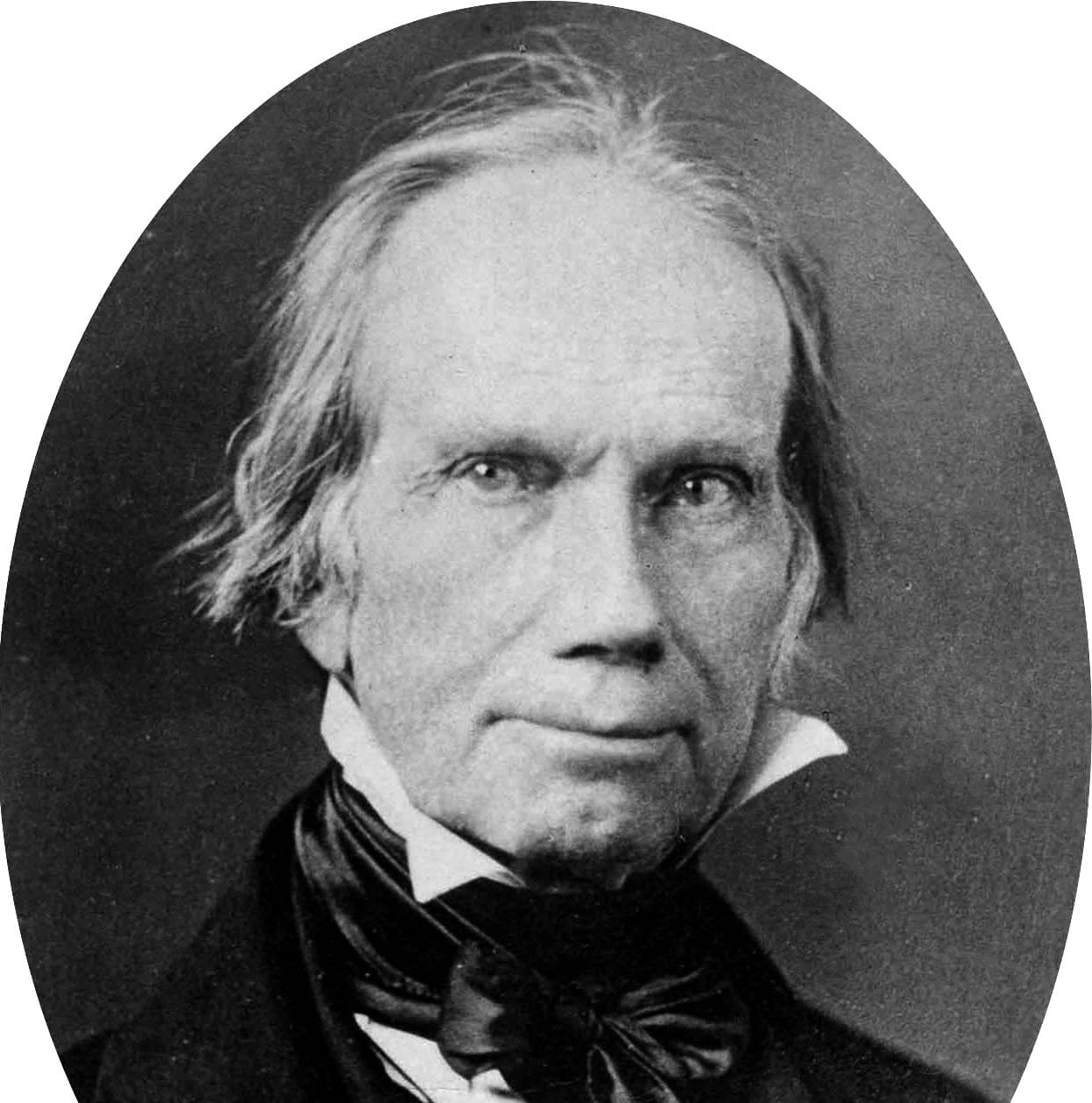

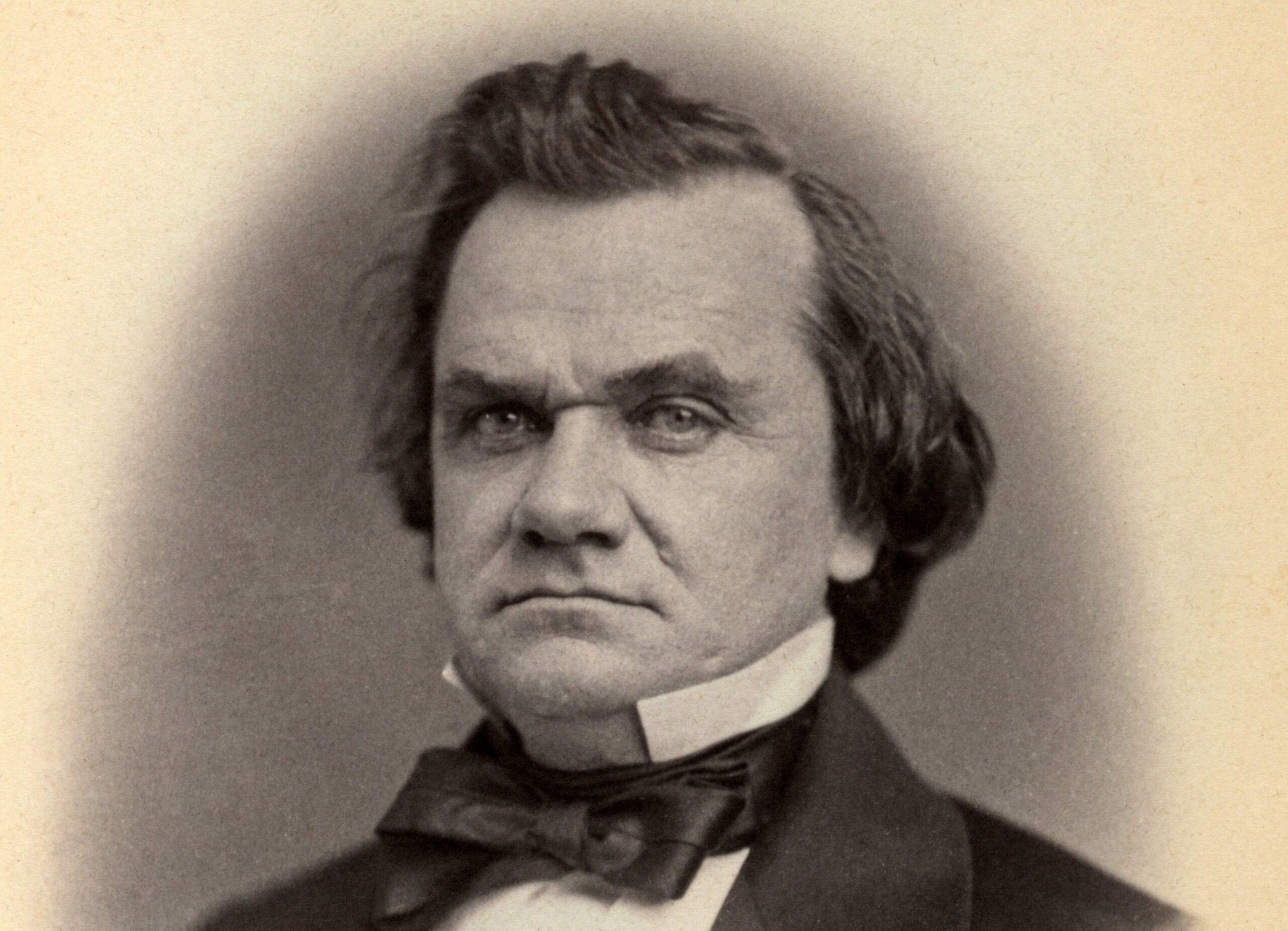

- 3. Thomas Hart Benton (1782–1858) was a senator from Missouri who was highly influential in that body. He was the first senator to serve five terms in office, completing thirty years of service from 1821–1851. Though a slaveholder, he eventually came to oppose slavery and the Compromise of 1850, which prompted the Missouri State Legislature to deny him a sixth term as its senator. During the debate over the Compromise of 1850 he was nearly shot by a Mississippi senator.

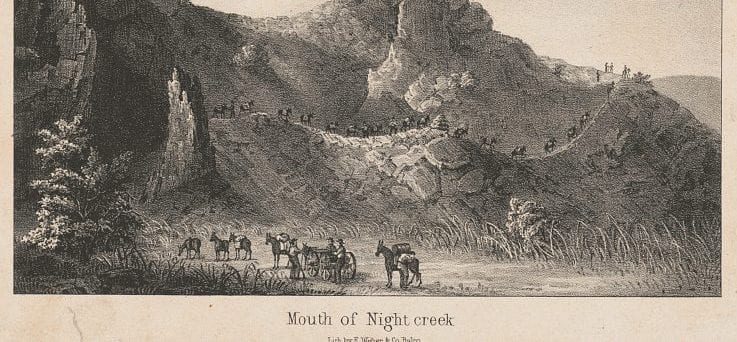

- 4. The case of Alexander McLeod concerned a dispute between Great Britain and the United States, over the seizure and destruction of the Caroline and the death of Amos Durfee (See Debate on the Constitutionality of the Mexican War). Canadian militia had crossed into United States territory to destroy the vessel, which was traveling to reinforce Canadian rebels (and Americans supporting them) attempting to gain independence from Great Britain. Amos Durfee was killed in the battle, and Alexander McLeod, a Canadian, was arrested in New York after boasting at a tavern that he had participated in the killing of Durfee. McLeod was eventually acquitted in a “curious spectacle” of a trial.

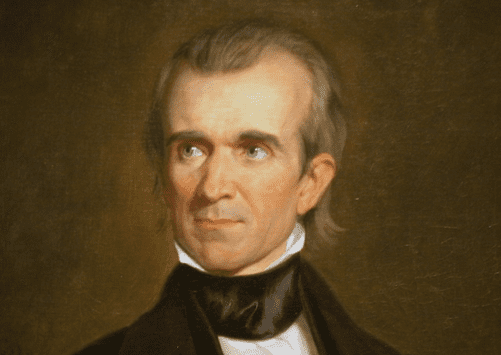

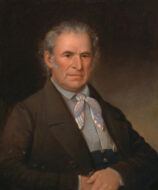

- 5. James Buchanan (1791–1868) was a senator from Pennsylvania who went on to serve as secretary of state and the 15th president of the United States. His presidency is poorly regarded by many historians who fault him for failing to prevent the outbreak of the Civil War.

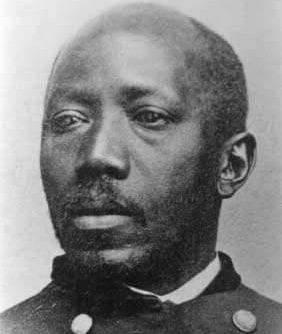

- 6. William King (1786–1853) was a senator from Alabama who served as president pro tempore of the Senate and as vice president of the United States for six weeks during Franklin Pierce’s presidency, before dying of tuberculosis in 1853.

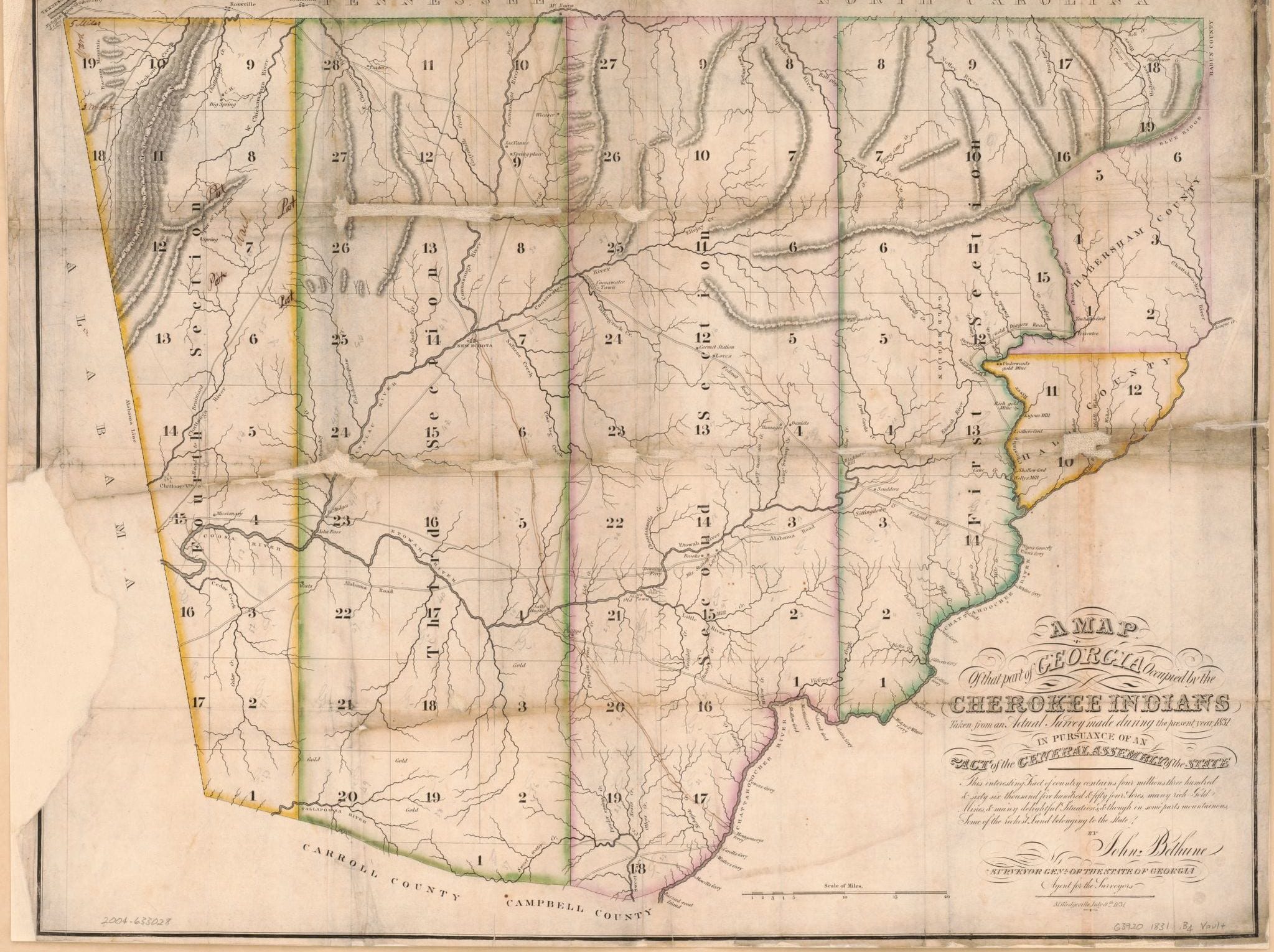

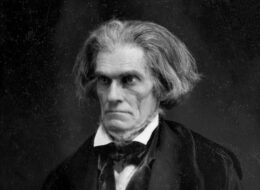

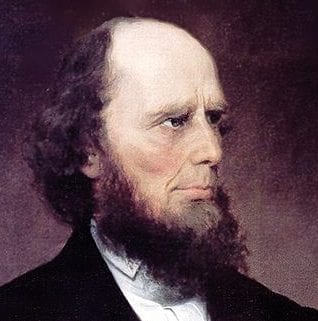

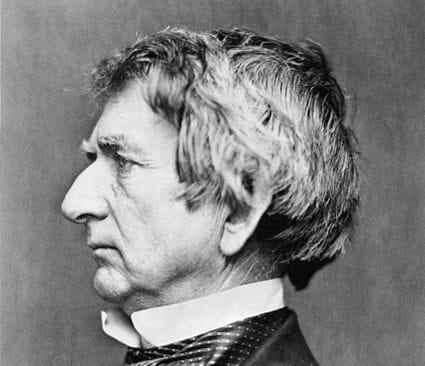

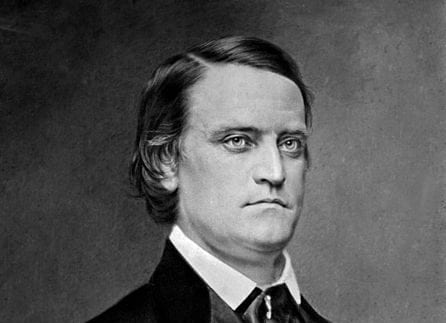

- 7. John C. Calhoun (1782–1850) was a senator from South Carolina who served as vice president during the administrations of John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, and secretary of state during the administrations of John Tyler and James K. Polk. He was an advocate of states’ rights and nullification and was one of the most distinguished political orators and thinkers of his generation.

- 8. The “old Federal party” refers to the Federalist Party, which contained major figures such as Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, and was dominant during the 1790s. The Whig Party, of which Henry Clay was a member, is often considered to descend from the Federalist Party. The “old Republican party” refers to the Republican Party, or Democratic-Republican Party, as historians often refer to it. That party was led by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, and eventually became the Democratic Party under Andrew Jackson in the 1830s and 1840s.

- 9. Calhoun may here be referring to Clay’s attempts, as Speaker of the House of Representatives back in the 1810s, to impose limits on debate in response to filibusters that often came from John Randolph, a Republican member from Virginia who frequently opposed Clay’s “War Hawk” measures. He may also be referring to the infamous “gag rule” that prevented anyone in the House of Representatives from discussing the issue of slavery that was enacted in the 1830s.

- 10. Calhoun is alluding to Clay’s unsuccessful attempt to win the presidency in 1840. Clay’s candidacy for the presidency was a series of such failures—having run a total of five times for the presidency but never succeeding.

- 11. Benton is trying to connect Clay’s attempt to restrict debate in the Senate to earlier Federalist attempts to limit certain kinds of speech in the Sedition Act, enacted in 1798.

Annual Message to Congress (1841)

December 07, 1841

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.