Introduction

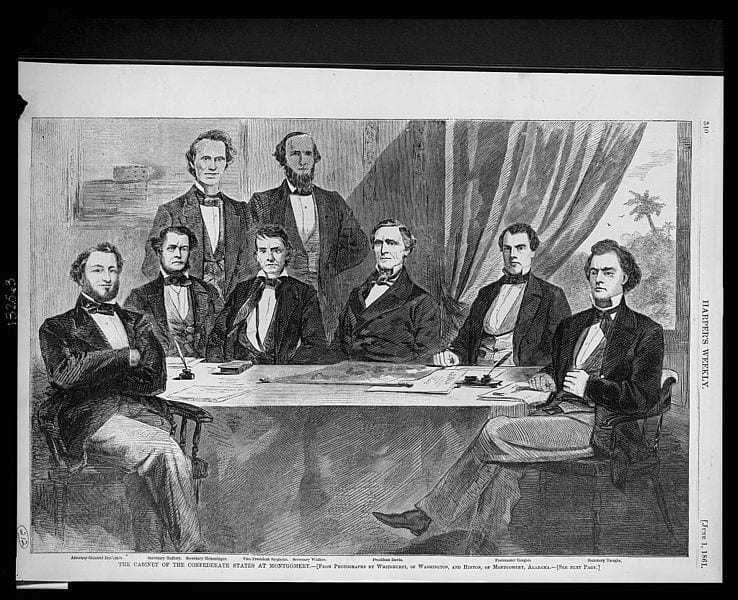

After his election to the presidency in November 1860, Abraham Lincoln received a letter from Alexander H. Stephens (1812–1883), the future vice president of the Confederacy. The two had been fellow members of the Whig Party when Lincoln served in the House of Representatives from 1847 to 1849. Writing after South Carolina claimed to have seceded from the United States on December 20, 1860, Stephens asked Lincoln on December 30 to do what he could “to save our common country.” Quoting Proverbs 25:11, Stephens suggested to Lincoln, “A word fitly spoken by you now would be like ‘apples of gold in pictures of silver.’”

Lincoln did not reply publicly to Stephens, believing that any public statement he made as he waited to assume office might be misunderstood and would only worsen the secession crisis. Lincoln did respond, however. Nestled among his complete speeches and writings are several fragments that represent Lincoln’s thoughts on a variety of issues (for another example, see Fragment on Slavery and Democracy). In focusing on the connection between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, Lincoln went to the heart of the cause of the Civil War. The nation was divided over how to understand the connection between its two founding documents. Was the Constitution and the will of the people—popular sovereignty—the ultimate authority, or did that authority derive from an even higher authority, the natural equality of all men declared in the Declaration?

All this is not the result of accident. It has a philosophical cause. Without the Constitution and the Union, we could not have attained the result; but even these are not the primary cause of our great prosperity. There is something back of these, entwining itself more closely about the human heart. That something is the principle of “liberty to all”—the principle that clears the path for all—gives hope to all—and by consequence, enterprise and industry to all.

The expression of that principle in our Declaration of Independence was most happy and fortunate. Without this, as well as with it, we could have declared our independence of Great Britain; but without it we could not, I think, have secured our free government and consequent prosperity. No oppressed people will fight and endure, as our fathers did, without the promise of something better than a mere change of masters.

The assertion of that principle, at that time, was the word “fitly spoken,” which has proved an “apple of gold” to us. The Union and the Constitution are the picture of silver subsequently framed around it. The picture was made not to conceal or destroy the apple but to adorn and preserve it. The picture was made for the apple—not the apple for the picture.

So let us act, that neither picture or apple shall ever be blurred or bruised or broken.

That we may so act, we must study and understand the points of danger.