No related resources

Introduction

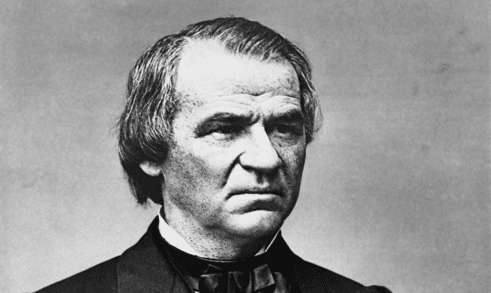

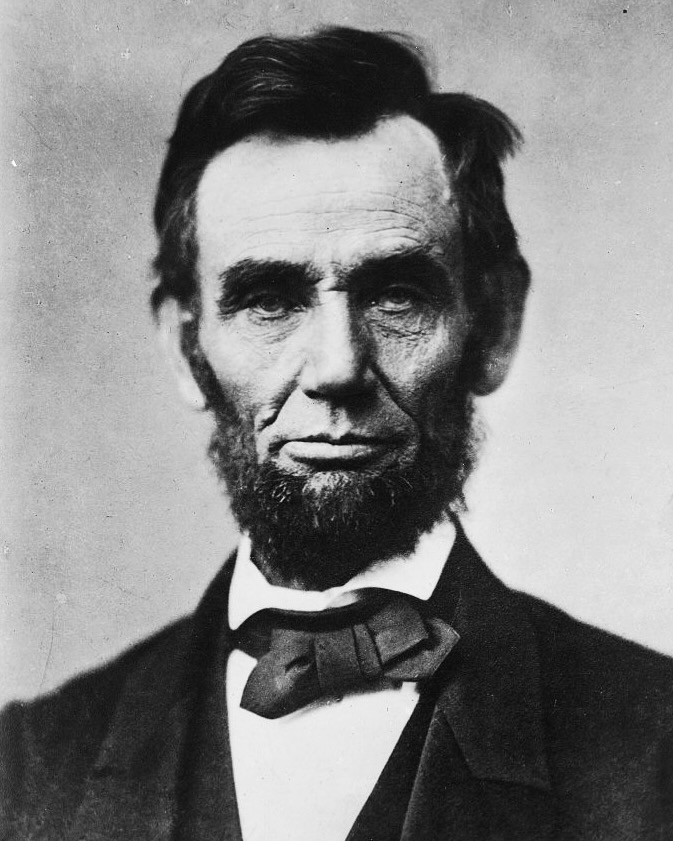

Abraham Lincoln’s victory in the presidential election in November 1860 also gave the new Republican Party control of the Thirty-Seventh Congress (1861–1863). The Southern rebellion that followed the election began with the fall of Fort Sumter in April 1861. With Congress out of session at the time, Lincoln issued several executive actions to address the logistics of defense. On July 4 Lincoln summoned the new Congress into a special session to defend the propriety of his actions, which included calling out militia, blockading Confederate ports, reallocating funds for defense, and suspending habeas corpus in certain places. Congress, led by a vocal minority of Radical Republicans, backed Lincoln on nearly every one of these issues.

Lincoln’s defense of his executive actions taken in the absence of Congress followed two lines of argumentation: necessity and constitutionality. Given that Congress was not in session at the time Fort Sumter was under direct threat, Lincoln justified his course of action as necessary to preserve the Union. However, Lincoln did not rest his argument solely on expediency. He also argued that his actions were constitutionally justifiable under Article II, which covers the executive power and states that the president is the commander in chief. As commander in chief, Lincoln claimed, he had a duty to respond to the attacks on federal garrisons. Perhaps the most controversial of Lincoln’s actions was his suspension of habeas corpus. Article I, on the legislative power, section 9 states “the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.” The Constitution does not expressly authorize or prohibit the president from suspending the writ.

By the time Lincoln sent his message to the special session of Congress, Chief Justice Roger Taney in Ex parte Merryman (May 1861) had already decided that only Congress could suspend the writ, even during a time of insurrection. Lincoln’s argument that the president also held that right by virtue of his duty as commander in chief raised important questions about the proper balance of power between Congress and the president during a time of war.

Abraham Lincoln, Message to Congress, July 4, 1861, Second Printed Draft, with Changes in Lincoln’s Hand, May 1861, Abraham Lincoln Papers: Series 1, General Correspondence, Manuscript/Mixed Material, https://www.loc.gov/item/mal1057200/

Fellow citizens of the Senate and House of Representatives:

Having been convened on an extraordinary occasion, as authorized by the Constitution, your attention is not called to any ordinary subject of legislation.

At the beginning of the present presidential term, four months ago, all the functions of the federal government were found to be entirely generally suspended within the several states of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida, excepting only those of the Post Office Department.

Finding this condition of things,1 and believing it to be an imperative duty upon the incoming executive to prevent, if possible, the consummation of such attempt to destroy the federal Union, a choice of means to that end became indispensable. This choice was made and was declared in the inaugural address. The policy chosen looked to the exhaustion of all peaceful measures before a resort to any stronger ones. It sought only to hold the public places and property not already wrested from the government, and to collect the revenue; relying for the rest, on time, discussion, and the ballot-box. It promised a continuance of the mails, at government expense, to the very people who were resisting the government; and it gave repeated pledges against any disturbance to any of the people, or any of their rights. Of all that which a president might constitutionally, and justifiably, do in such a case, everything was forborne, without which, it was believed possible to keep the government on foot.

On the 5th of March, a letter of Major Anderson, commanding at Fort Sumter, written on the 28th of February, and received at the War Department on the 4th of March, was, by that department, placed in his hands. This letter expressed the professional opinion of the writer that reenforcements could not be thrown into that fort within the time for his relief, rendered necessary by the limited supply of provisions, and with a view of holding possession of the same, with a force of less than twenty thousand good and well-disciplined men. . . .It was believed, however, that to so abandon that position, under the circumstances, would be utterly ruinous; that the necessity under which it was to be done would not be fully understood; that by many, it would be construed as a part of a voluntary policy; that at home, it would discourage the friends of the Union, embolden its adversaries, and go far to insure to the latter, a recognition of independence abroad; that, in fact, it would be our national destruction consummated. This could not be allowed.2

And this issue embraces more than the fate of these United States. It presents to the whole family of man the question, whether a constitutional republic, or a democracy—a government of the people, by the same people—can, or cannot, maintain its territorial integrity against its own domestic foes. It presents the question, whether discontented individuals, too few in numbers to control administration, according to organic law,3 in any case, can always, upon the pretenses made in this case, or on any other pretenses, or arbitrarily, without any pretense, break up their government, and thus practically put an end to free government upon the earth. It forces us to ask: “Is there, in all republics, this inherent and fatal weakness?” “Must a government, of necessity, be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?”

So viewing the issue, no choice was left but to call out the war power of the government; and so to resist force, employed for its destruction, by force, for its preservation. . . .

Soon after the first call for militia, it was considered a duty to authorize the commanding general, in proper cases, according to his discretion, to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus; or, in other words, to arrest and detain, without resort to the ordinary processes and forms of law, such individuals as he might deem dangerous to the public safety. This authority has purposely been exercised but very sparingly. Nevertheless, the legality and propriety of what has been done under it are questioned, and the attention of the country has been called to the proposition that one who is sworn to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed” should not himself violate them. Of course some consideration was given to the questions of power, and propriety, before this matter was acted upon. The whole of the laws which were required to be faithfully executed were being resisted, and failing of execution in nearly one-third of the states. Must they be allowed to finally fail of execution, even had it been perfectly clear that by the use of the means necessary to their execution, some single law, made in such extreme tenderness of the citizen’s liberty that practically, it relieves more of the guilty, than of the innocent, should, to a very limited extent, be violated? To state the question more directly, are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated? Even in such a case, would not the official oath be broken if the government should be overthrown, when it was believed that disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it? But it was not believed that this question was presented. It was not believed that any law was violated. The provision of the Constitution that “the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended unless when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it” is equivalent to a provision—is a provision—that such privilege may be suspended when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety does require it. It was decided that we have a case of rebellion, and that the public safety does require the qualified suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus which was authorized to be made. Now it is insisted that Congress, and not the executive, is vested with this power. But the Constitution itself is silent as to which, or who, is to exercise the power; and as the provision was plainly made for a dangerous emergency, it cannot be believed that the framers of the instrument intended that in every case, the danger should run its course, until Congress could be called together; the very assembling of which might be prevented, as was intended in this case, by the rebellion.

No more extended argument is now offered; as an opinion, at some length, will probably be presented by the attorney general. Whether there shall be any legislation upon the subject, and if any, what, is submitted entirely to the better judgment of Congress. . . .

- 1. The states that had seceded from the Union formed the Confederate States of America and were in the process of seeking recognition by foreign governments. Rebel forces seized forts, arsenals, dockyards, customhouses and other federal property.

- 2. The issue to be decided here was whether a democratic nation having decided a course of action at the ballot-box should tolerate an act of aggression (the attack on Fort Sumter) by a minority.

- 3. “Organic law” is a term used to designate the fundamental laws of a political order.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.