Introduction

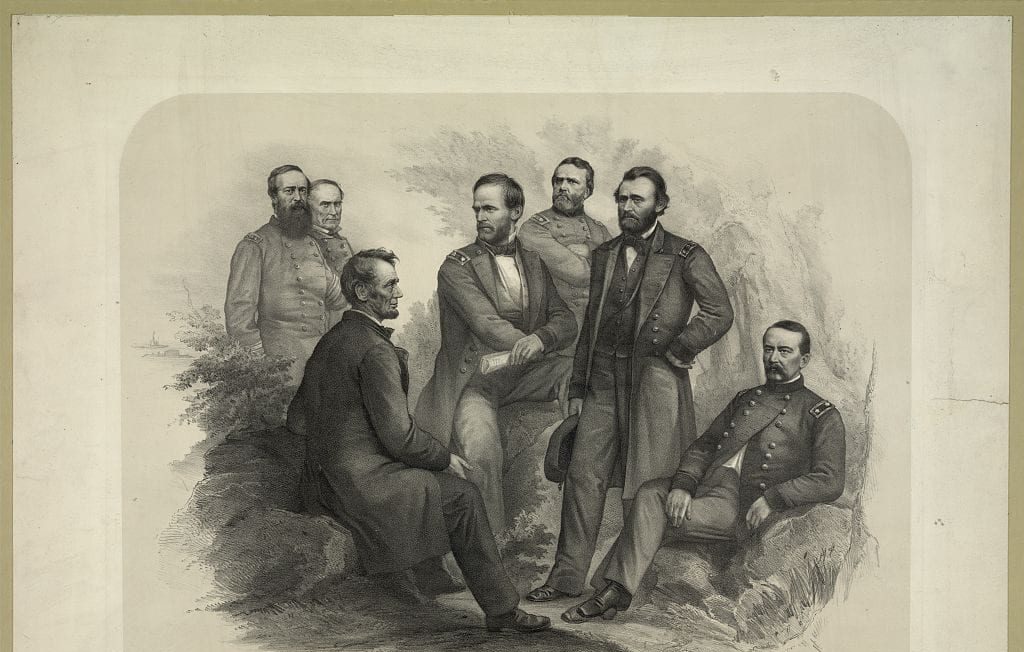

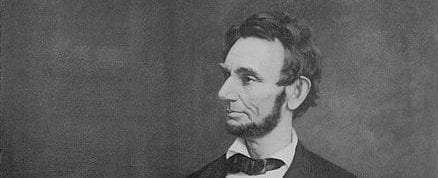

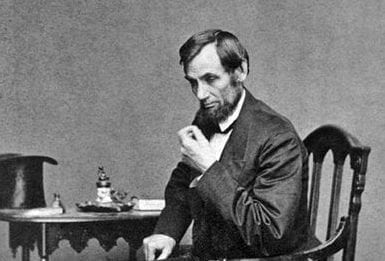

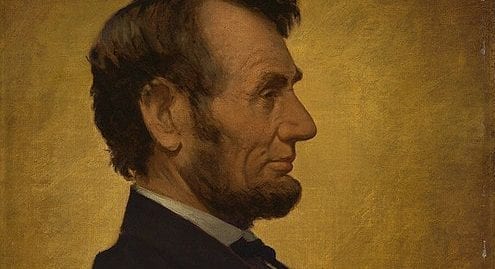

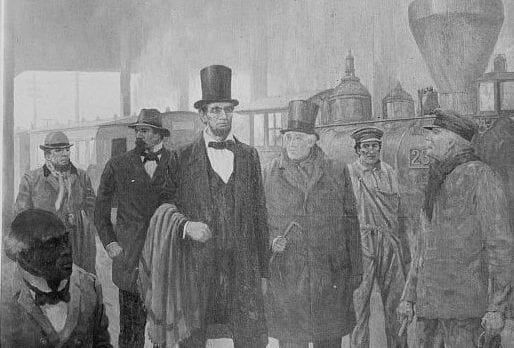

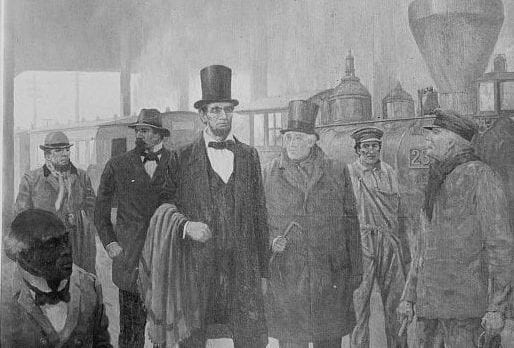

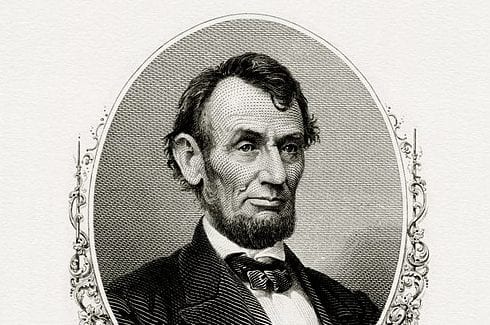

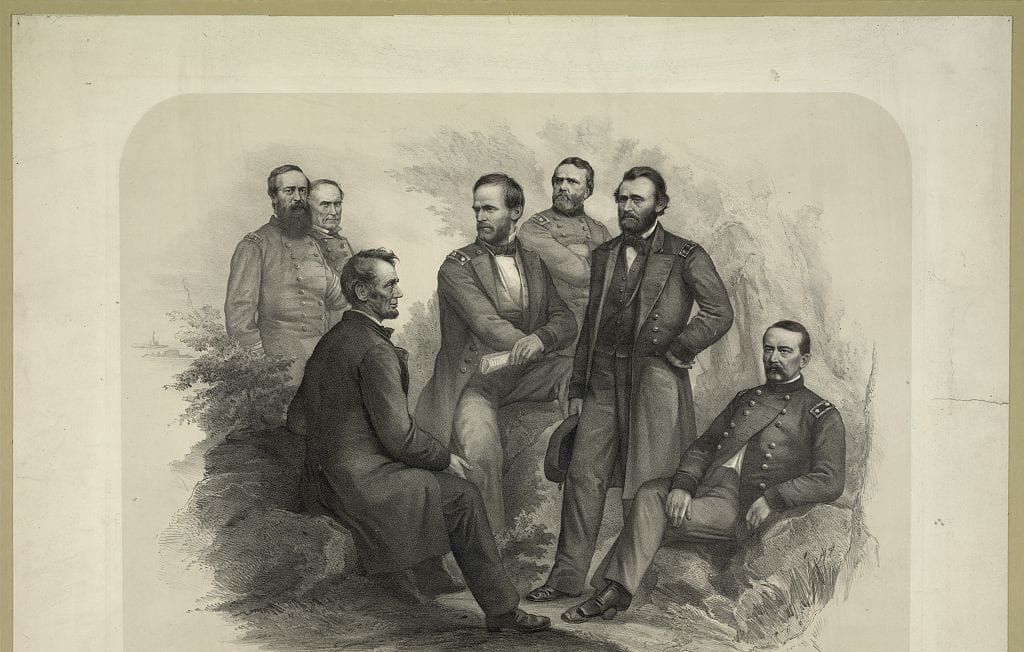

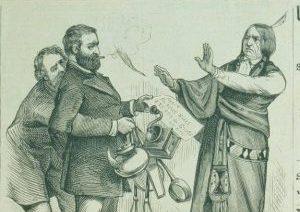

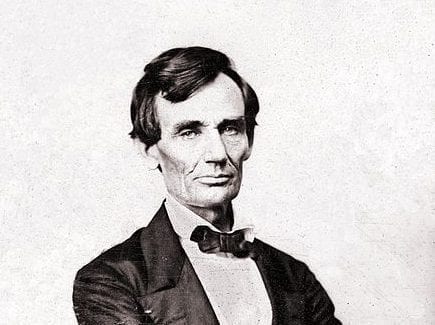

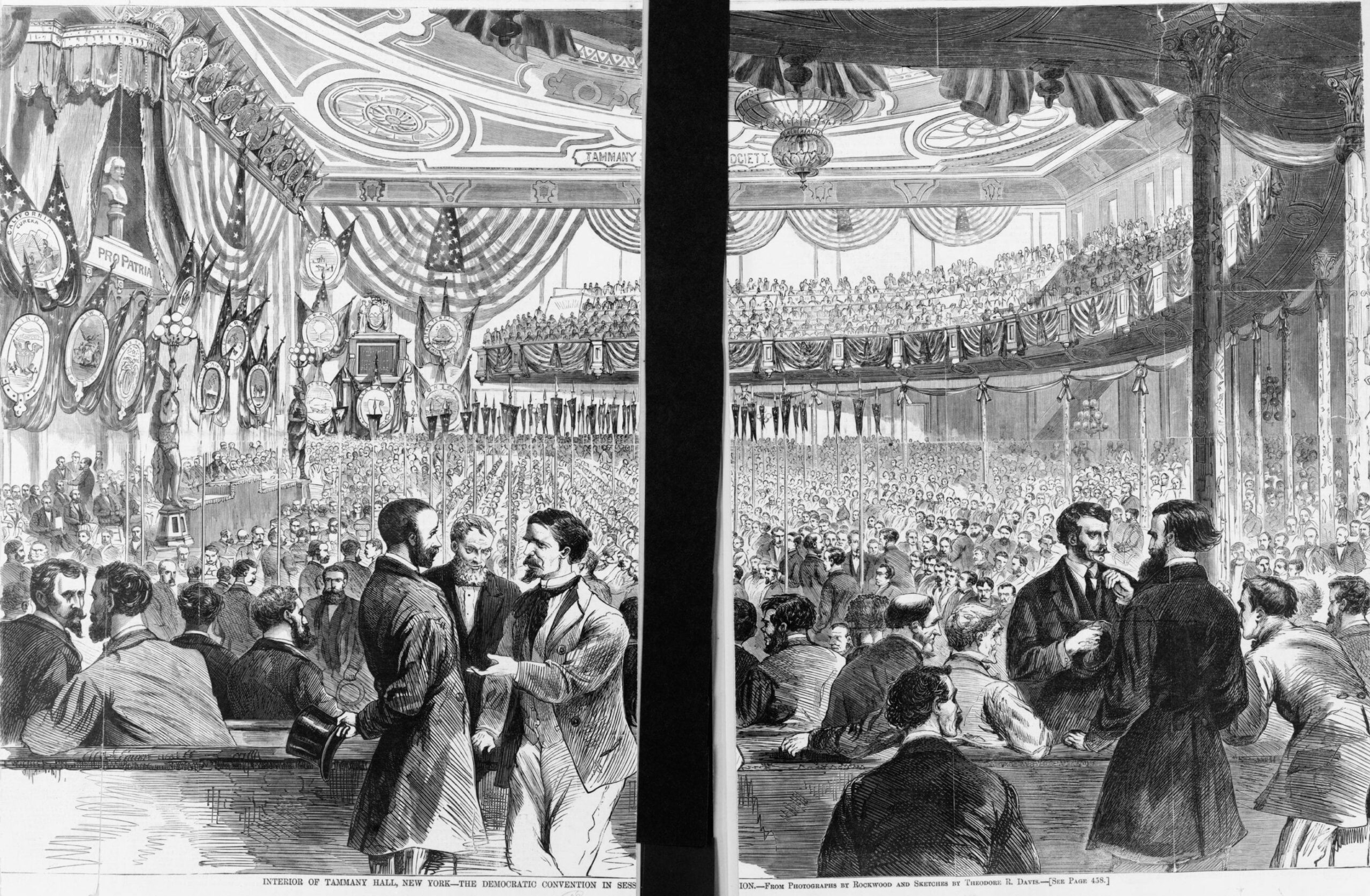

The election of 1864 pitted President Lincoln and Vice President Andrew Johnson (1808–1875) on the National Union Ticket (the renamed Republican Party) against Democratic candidates George B. McClellan (1826–1885), a former Union general, and George Pendleton (1825–1889). Clement Vallandigham (1820–1871), the notorious Copperhead from Ohio (See To Erastus Corning et al.), wrote a peace platform for the Democratic Party that called for “immediate cessation of hostilities.” Though Lincoln’s prospects for reelection looked dubious in late summer of 1864 given war-weariness and dissatisfaction with Republican policies on the draft, emancipation, and civil liberties, the tide decisively turned after Sherman captured Atlanta in early September. On November 8, Lincoln defeated McClellan handily by winning 55 percent of the popular vote and 212 of 233 electoral votes. The only states McClellan carried were Kentucky and New Jersey. Union soldiers overwhelmingly voted for Lincoln, giving him 78 percent of their votes.

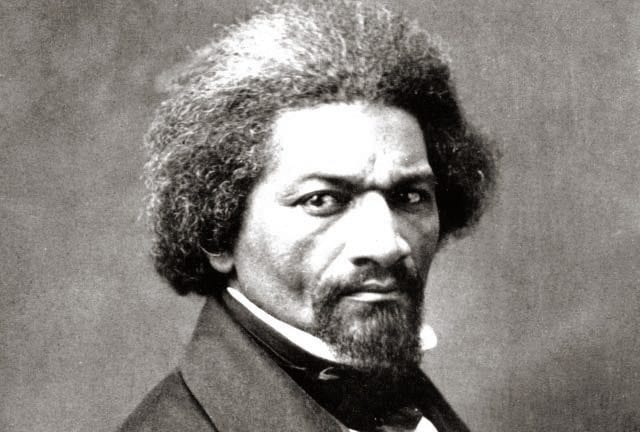

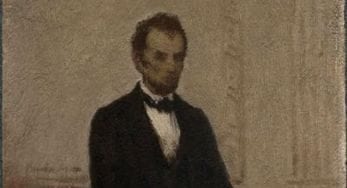

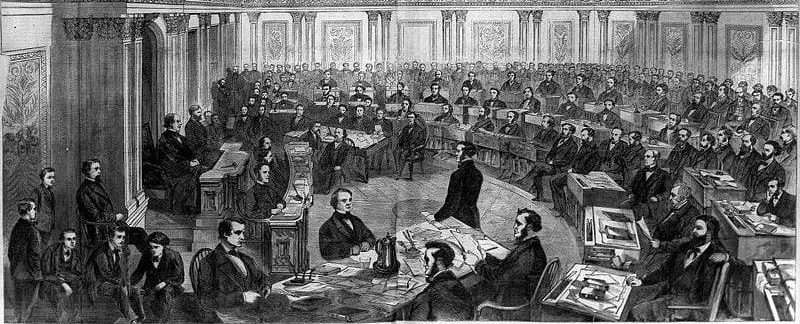

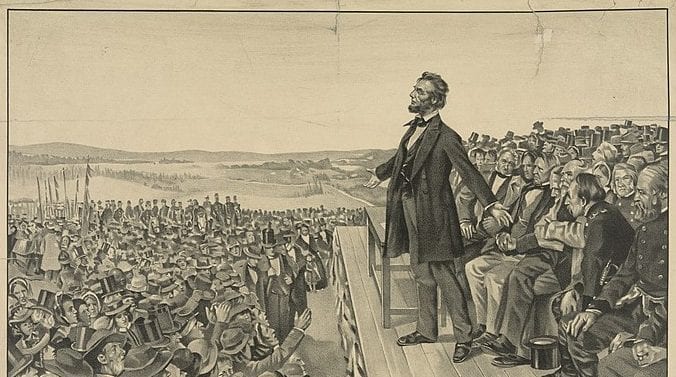

Two days after the election, on the evening of November 10, a group of serenaders came to the White House to celebrate Lincoln’s victory. In his impromptu remarks to them, Lincoln described the wider significance of the election as a demonstration to the nation and the world of the viability of democratic institutions during a time of crisis. In its call for unity and its expression of regard for those on the other side, it anticipated Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address.

—Joseph R. Fornieri and David Tucker

Abraham Lincoln, Remarks in Response to a Serenade, online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/342170.

It has long been a grave question whether any government not too strong for the liberties of its people, can be strong enough to maintain its own existence, in great emergencies.

On this point the present rebellion brought our Republic to a severe test; and a presidential election occurring in regular course during the rebellion added not a little to the strain. If the loyal people, united, were put to the utmost of their strength by the rebellion, must they not fail when divided, and partially paralyzed, by a political war among themselves?

But the election was a necessity.

We cannot have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forgo or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us. The strife of the election is but human nature practically applied to the facts of the case. What has occurred in this case must ever recur in similar cases. Human nature will not change. In any future great national trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak and as strong; as silly and as wise; as bad and good. Let us, therefore, study the incidents of this, as philosophy to learn wisdom from, and none of them as wrongs to be revenged.

But the election, along with its incidental, and undesirable strife, has done good too. It has demonstrated that a people’s government can sustain a national election in the midst of a great civil war. Until now it has not been known to the world that this was a possibility. It shows also how sound and how strong we still are. It shows that, even among candidates of the same party, he who is most devoted to the Union, and most opposed to treason, can receive most of the people’s votes. It shows also, to the extent yet known, that we have more men now than we had when the war began. Gold is good in its place; but living, brave, patriotic men are better than gold.

But the rebellion continues; and now that the election is over, may not all, having a common interest, reunite in a common effort to save our common country? For my own part I have striven, and shall strive to avoid placing any obstacle in the way. So long as I have been here I have not willingly planted a thorn in any man’s bosom.

While I am deeply sensible to the high compliment of a reelection; and duly grateful, as I trust, to Almighty God for having directed my countrymen to a right conclusion, as I think, for their own good, it adds nothing to my satisfaction that any other man may be disappointed or pained by the result.

May I ask those who have not differed with me, to join with me, in this same spirit toward those who have?

And now, let me close by asking three hearty cheers for our brave soldiers and seamen and their gallant and skillful commanders.