Introduction

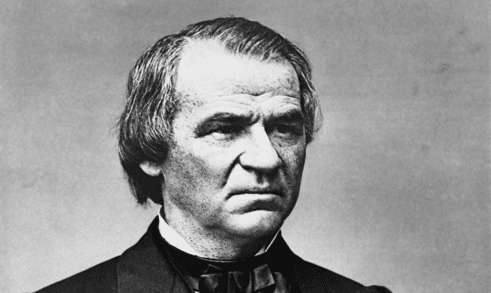

Information about South’s loyalties and about the state of the freedmen was crucial to the reconstruction efforts from the time of Carl Schurz’s “Report on the Condition of the South”. Any critique of President Andrew Johnson’s policy depended, at least in part, on a demonstration that disloyal Southerners were coming to power and that they were not respecting the civil rights of freedmen. Some criticisms of the radical plans for military enforcement of Reconstruction depended on the claim that such extreme measures were unnecessary given the new loyalty among the Southerners and their willingness to accept the emancipation of the freedmen. Accurate information was, however, not easy to come by and not always accepted when it was gathered. One such source of information was Congress’s Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which sent sub-committees throughout the South gathering information about conditions for freedmen and loyalists. Another source of information was the army, which was in charge of registering voters, overseeing elections, and protecting freedmen while the Southern states were reconstructing themselves pursuant to the Reconstruction Acts. A collection of such reports was delivered by the Secretary of War John Schofield (1831-1906), a former Union general, to Congress soon after President Ulysses S. Grant was elected in 1868 at the 3rd and final session of the 40th Congress. The reports detailed the conditions throughout the South. These excerpts describe Texas in the period following the war. Texas was one of three states that had not yet been re-admitted into the Union when Grant took his oath of office.

Source: Message of the President of the United States and Accompanying Documents to the Two Houses of Congress at the Commencement of the Third Session of the Fortieth Congress, Report of the Secretary of War, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1868), 705, 1051-1052.

Report of the Secretary of War

MR. PRESIDENT: I have the honor to submit a general report of the operations of this department since the last annual report of the Secretary of War, with the reports of the chiefs of bureaus and military commanders for the same period. . . .

The precise objects of the [secret] organizations cannot be readily explained, but seem, in this State, to be to disarm, rob, and in many cases murder Union men and negroes, and as occasion may offer, murder United States officers and soldiers; also to intimidate everyone who knows anything of the organization but who will not join it.

The civil law east of the Trinity River is almost a dead letter. In some counties the civil officers are all, or a portion of them, members of the Klan. In other counties where the civil officers will not join the Klan, or some other armed band, they have been compelled to leave their counties. . . .

In many counties where the county officers have not been driven off, their influence is scarcely felt. What political end, if any, is aimed at by these bands I cannot say, but they attend in large bodies the political meetings (barbecues) which have been and are still being held in various parts of this State under the auspices of the democratic clubs of the different counties.

The speakers encourage their attendance, and in several counties men have been indicated by name from the speaker’s stand, as those selected for murder. The men thus pointed out have no course left them but to leave their homes or be murdered on the first convenient opportunity.

The murder of Negroes is so common as to render it impossible to keep an accurate account of them.

Many of the members of these bands of outlaws are transient persons in the State, the absence of railroads and telegraphs and great length of time required to communicate between remote points facilitating their devilish purposes.

These organizations are evidently countenanced, or at least not discouraged, by a majority of the white people in the counties where the bands are most numerous. They could not otherwise exist.

I have given this matter close attention, and am satisfied that a remedy to be effective must be gradually applied and continued with the firm support of the army until these outlaws are punished or dispersed.

They cannot be punished by the civil courts until some examples by military commissions show that men can be punished in Texas for murder and kindred crimes. Perpetrators of such crimes have not heretofore, except in very rare instances, been punished in this State at all.

Free speech and a free press, as the terms are generally understood in other States, have never existed in Texas. In fact, the citizens of other States cannot appreciate the state of affairs in Texas without actually experiencing it. The official reports of lawlessness and crime, so far from being exaggerated, do not tell the whole truth.

Jefferson is the center from which most of the trade, travel, and lawlessness of eastern Texas radiate, and at this point or its vicinity there should be stationed about a regiment of troops. The recent murder at Jefferson of Hon. G. W. Smith, a delegate to the constitutional convention, has made it necessary to order more troops to that point. This movement weakens the frontier posts to such an extent as to impair their efficiency for protection against Indians, but the bold, wholesale murdering in the interior of the State seems at present to present a more urgent demand for the troops than Indian depredations. The frontier posts should, however, be re-enforced if possible, as it is not improbable that the Indians from the northwest, after having suffered defeat there, will make heavy incursions into Texas. . . .

The educational work has been vigorously prosecuted. The measure of success attained is quite gratifying considering the obstacles that have been encountered – the poverty of the freedmen, the small amount of aid received from benevolent associations at the north, and, in the more remote sections, the prejudice and opposition of white citizens. In May the total number of schools in operation was 217, with 244 teachers and 10,971 pupils.

While the freedmen, as a class, exhibit a very general interest in religious matters, many of their habit still show the debasing influence of the slave system. Prominent among these is the want of a due appreciation of the obligations of the marriage contract. In this respect, however, their conduct is undergoing much improvement, and cases of desertion of wife and family are becoming rare.

The condition of society in the more remote and sparsely settled parishes is greatly disorganized. In some sections the treatment of the colored people has been deplorable. Outrage and crimes of every description have been perpetrated upon them with impunity. In these sections the character of the local magistracy is not as high as could be desired, and many of them have connived at the escape of offenders, while some have even participated in the outrages. In other sections lawless ruffians have overawed the civil authorities, “Vigilance Committees” and “Ku-klux Klans,” disguised by night, have burned the dwellings and shed the blood of unoffending freedmen. In many cases of brutal murder brought before the civil authorities, verdicts of justifiable homicide in self-defense have been rendered. The agents of the bureau, in obedience to their instructions, have exerted all the powers confided to them for the protection of the freed people, first referring the cases to the civil officials, and then, if justice is not rendered, calling on the military authorities for their action. For a few months past the assistant commissioner reports a decrease in the number of outrages committed, and more efficient measures on the part of the civil authorities for the apprehension and punishment of the perpetrators. . . .

The unsettled condition of this district has rendered necessary the distribution of a large military force over the State.

The commanding officers of military posts are also acting as agents of the bureau for their respective districts, so that a comparatively small force of civilian agents are on duty in this State. By these officers the operations of the bureau have been conducted as efficiently as circumstances would permit. They have power to hear and adjudicate cases to which freedmen are parties, and to impose and collect fines. Their mode of procedure has been conformed to that prescribed by State laws for justices of the peace, though their jurisdiction has not been limited by the amount in controversy. They are forbidden to receive fees for any services rendered by them. Sheriffs and constables have been directed to execute the process of the bureau. Appeal lies from the bureau agent to the assistant commissioner of the State.

The magistrates and judges of the higher courts of law are, in general, fair and impartial in the discharge of their duties, but juries in their verdicts, and in the weight they give to testimony, have almost always discriminated against the freedmen.

A fearful amount of lawlessness and ruffianism has prevailed in Texas during the past year. Armed bands styling themselves Ku-Klux, &c., have practiced barbarous cruelties upon the freedmen. Murders by the desperadoes who have long disgraced this State are of common occurrence. The civil authorities have been overawed, and, in many cases, even the bureau and military forces have been powerless to prevent the commission of these crimes. From information on file in the office of the assistant commissioner it appears that in the month of March the number of freedmen murdered was 21; of white men, 15; the number of freedmen assaulted with the intent to kill, 11; white men, 7. In July the number of freedmen murdered was 32; white men, 7. It has been estimated by reliable authority that in August 1868, there were probably 5,000 indictments pending in the State for homicide, in some of its various degrees, in most cases downright murder. Yet since the close of the war only in one solitary case (that of a freedman who was hung at Houston) has punishment to the full extent of the law been awarded.

In consequence of this condition of affairs a kind of a quiet prevails among the freed people, lacking but little in all the essentials of slavery. In the more remote districts, where bureau agents are 50 or 100 miles apart, and stations of troops still further distant, freedmen do not dare or presume to act in opposition to the will of their late masters. They make no effort to exercise rights conferred upon them by the acts of Congress, and few even of Union men are brave enough, or rather foolhardy enough, to advise them in anything antagonistic to the sentiments of the people lately in rebellion.

Annual Message to Congress (1868)

December 09, 1868

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.