This letter is part of our Four-Act Drama, a Constitutional Convention role-playing scheme for educators. For more information on our comprehensive exhibit on the Constitutional Convention, click here.

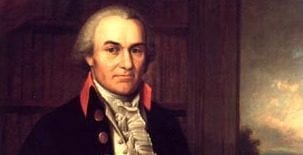

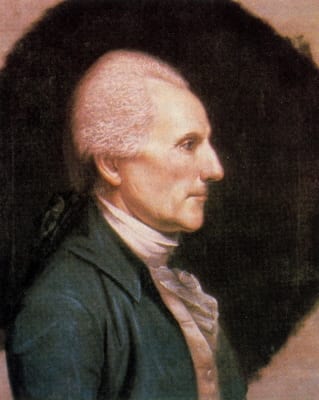

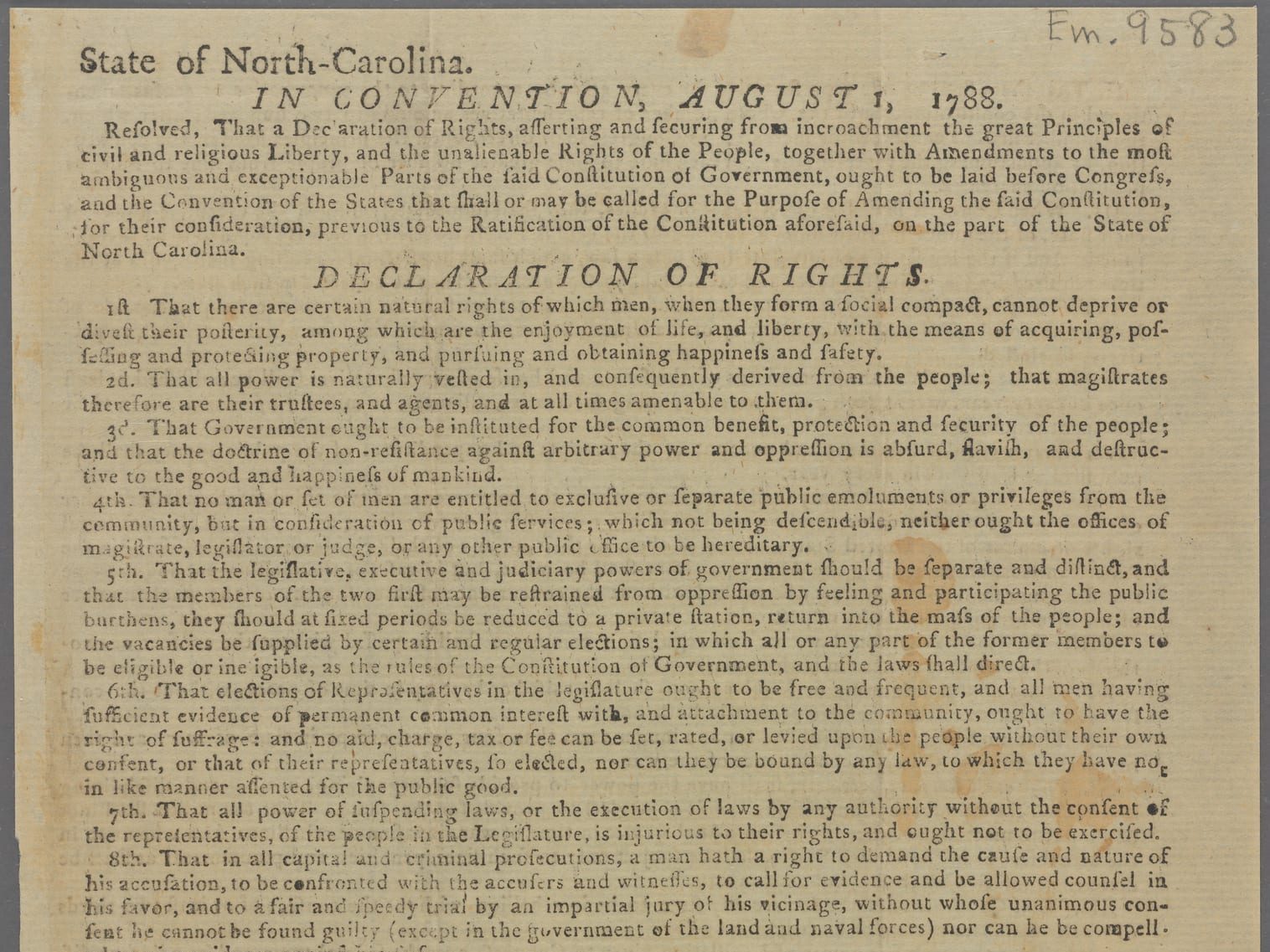

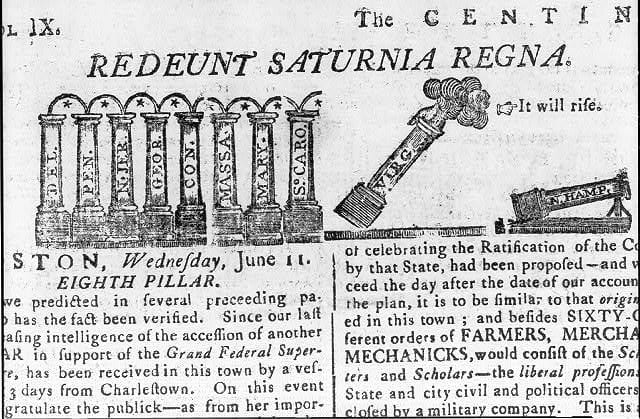

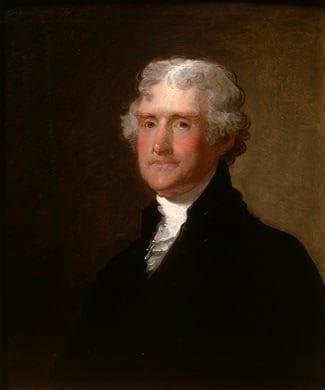

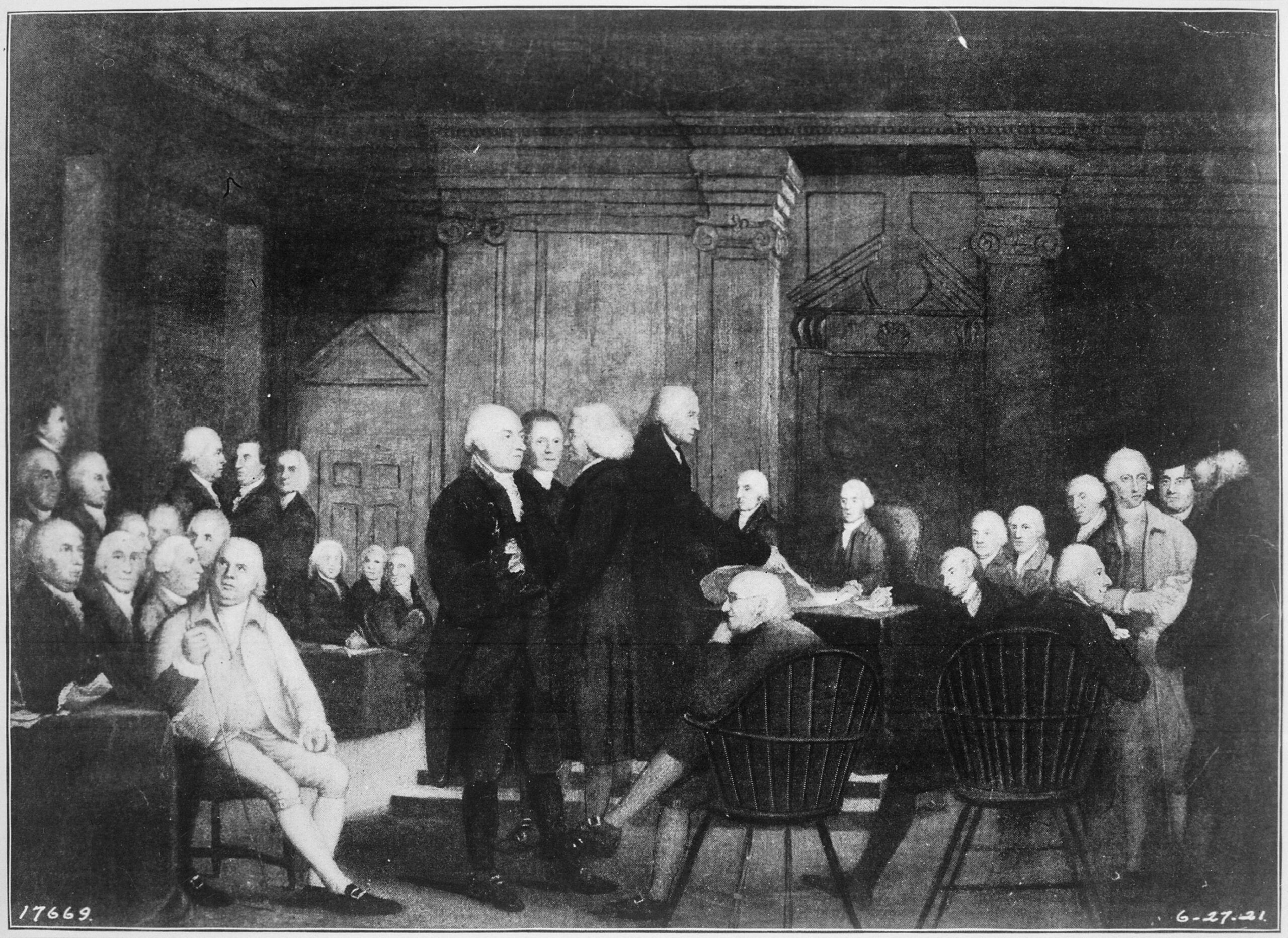

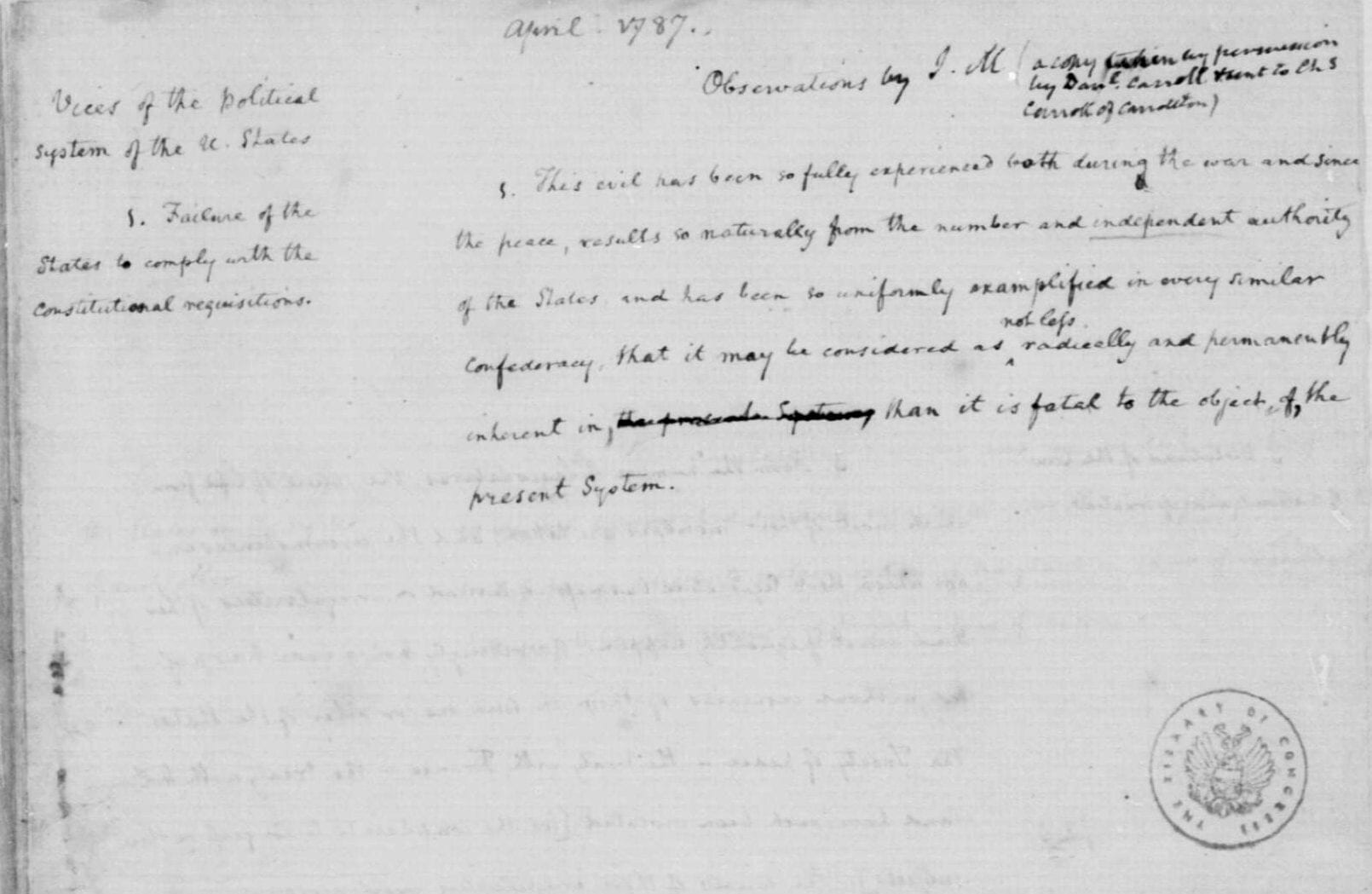

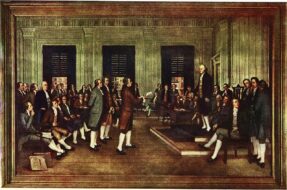

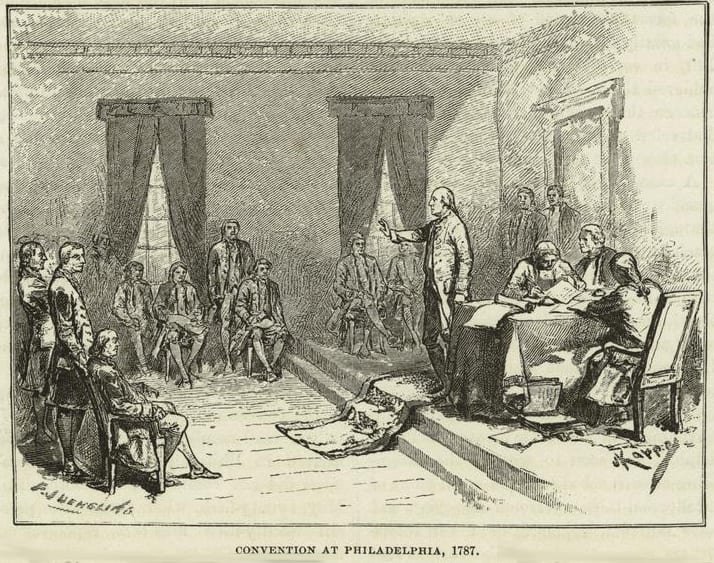

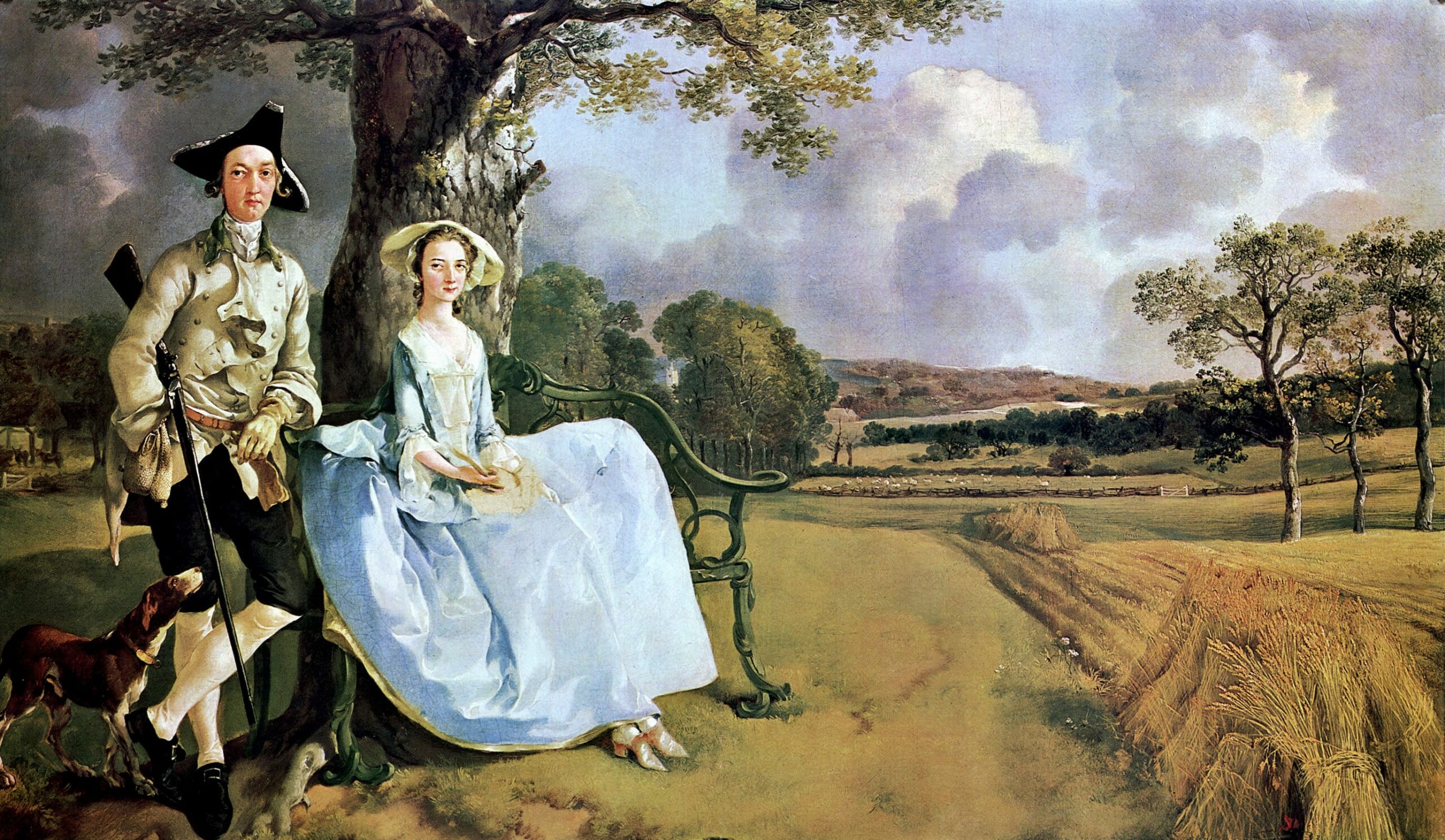

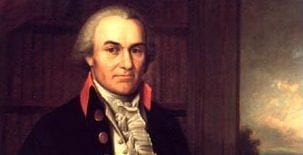

Act I concludes with Edmund Randolph’s (1753-1813) introduction of the Virginia Plan, which caused extensive debates and led many delegates to recognize that the Convention would likely last longer than initially anticipated. While this proposal sought to address the nation’s challenges under the Articles of Confederation, it faced considerable opposition. Delegates from Connecticut, Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Maryland voiced strong criticism of the plan. These delegates not only favored preserving the confederation but also argued that the Convention had overstepped its Congressional mandate by attempting to establish a new national government. The Confederation Congress Authorization, granted on February 21, 1787, had permitted the Convention solely “for the purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation.” By introducing the Virginia Plan, they claimed, the Convention was surpassing the reach of its authority.

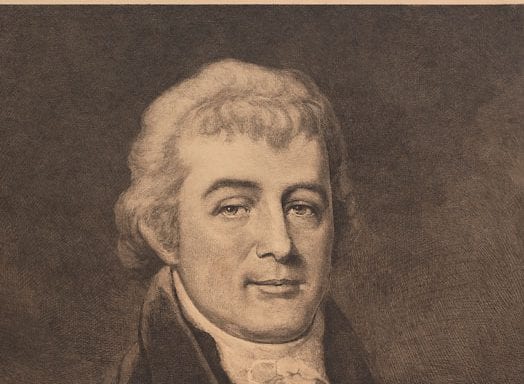

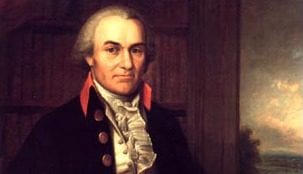

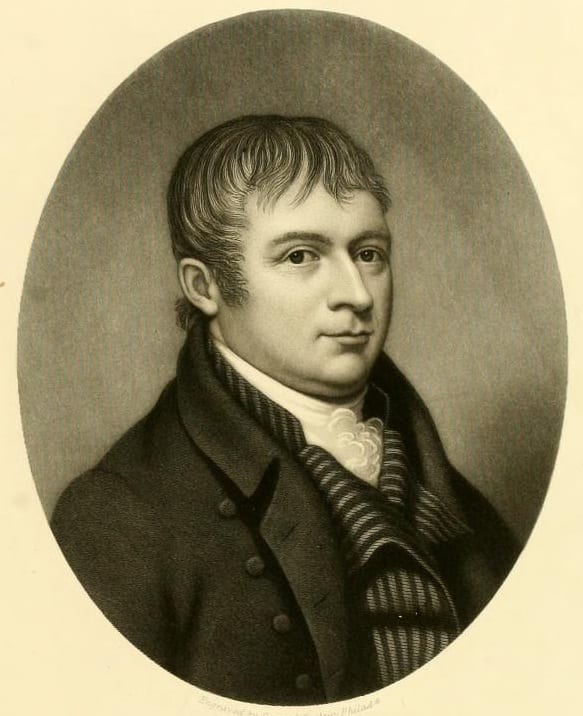

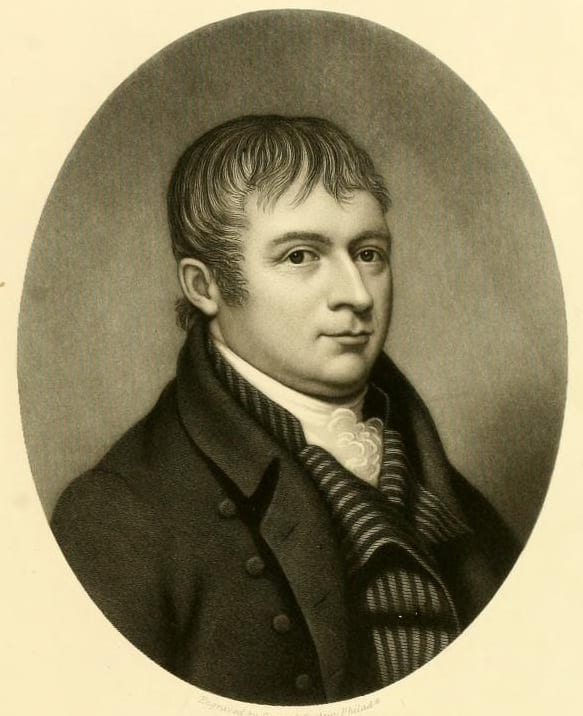

Although the Convention approved a version of the Virginia Plan in early June, delegates from smaller states opposed its proposal of proportional representation in both houses of Congress. These delegates instead supported the New Jersey Plan, introduced by William Paterson (1745–1806). This alternate plan retained the principle of state equality from the Articles of Confederation while increasing Congressional authority by granting additional powers. It also provided for a federal executive and a federal judiciary. This led to a significant impasse, with delegates from smaller states supporting the New Jersey Plan and delegates from the larger states continuing to support the Virginia Plan.

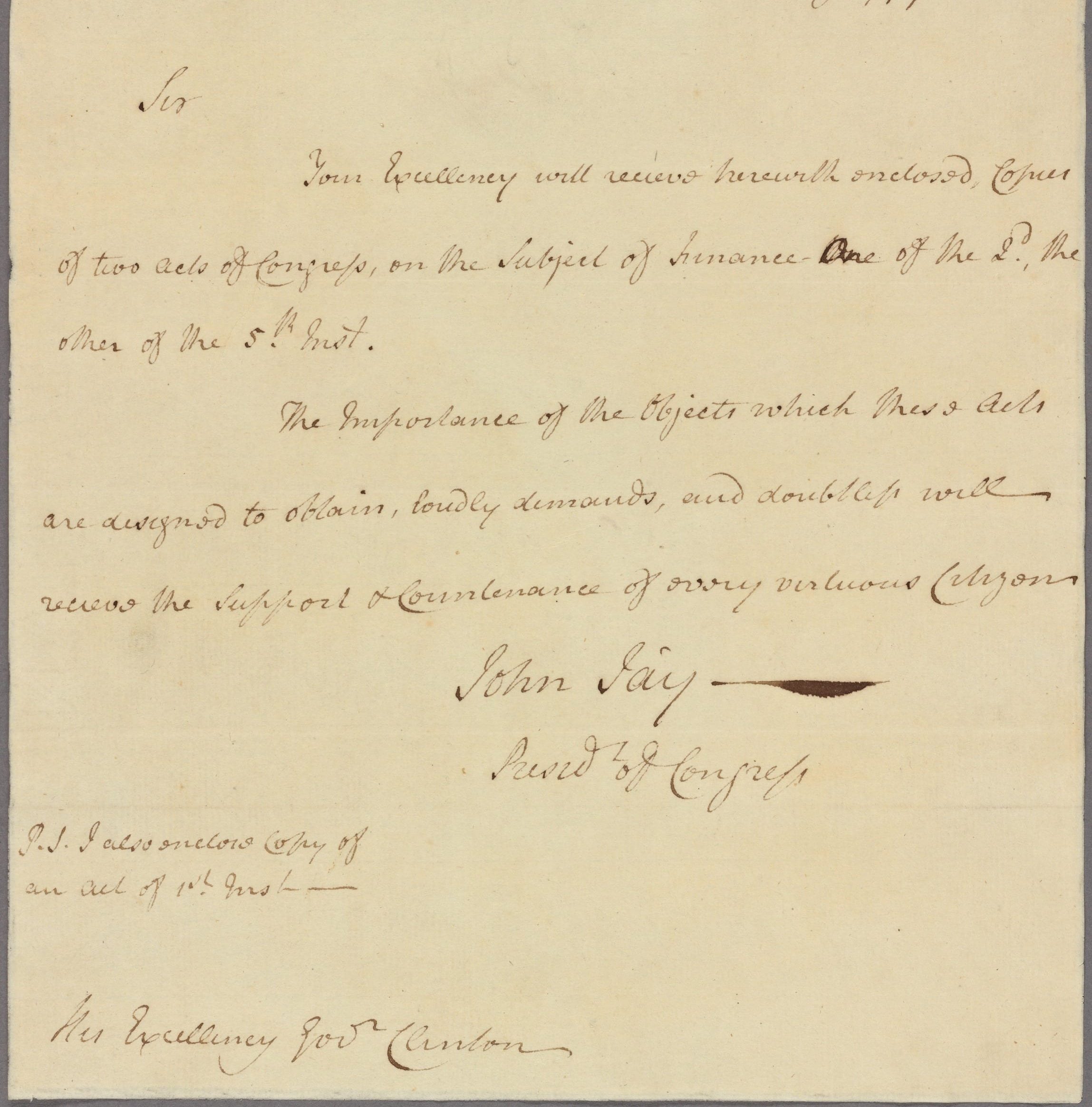

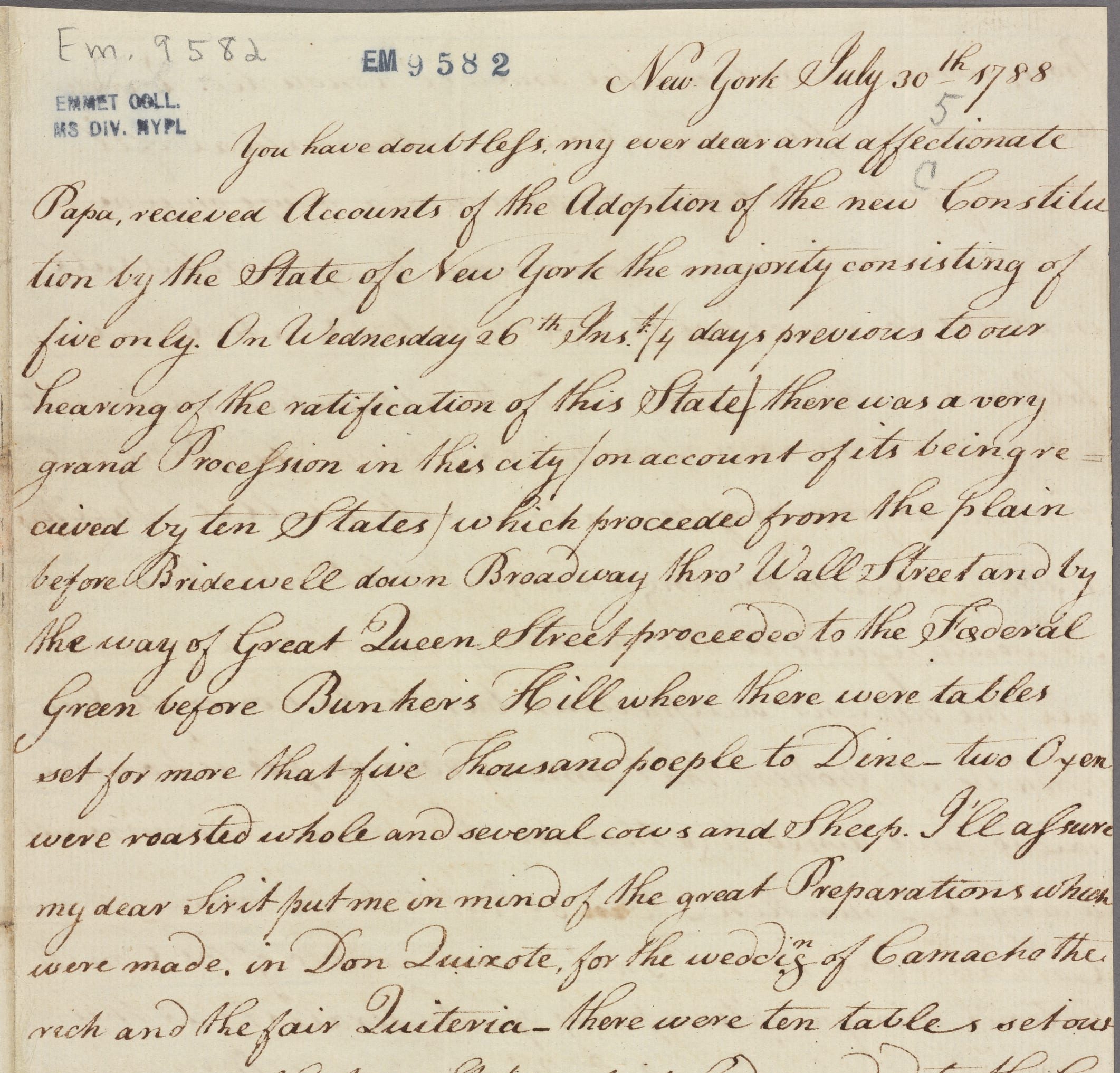

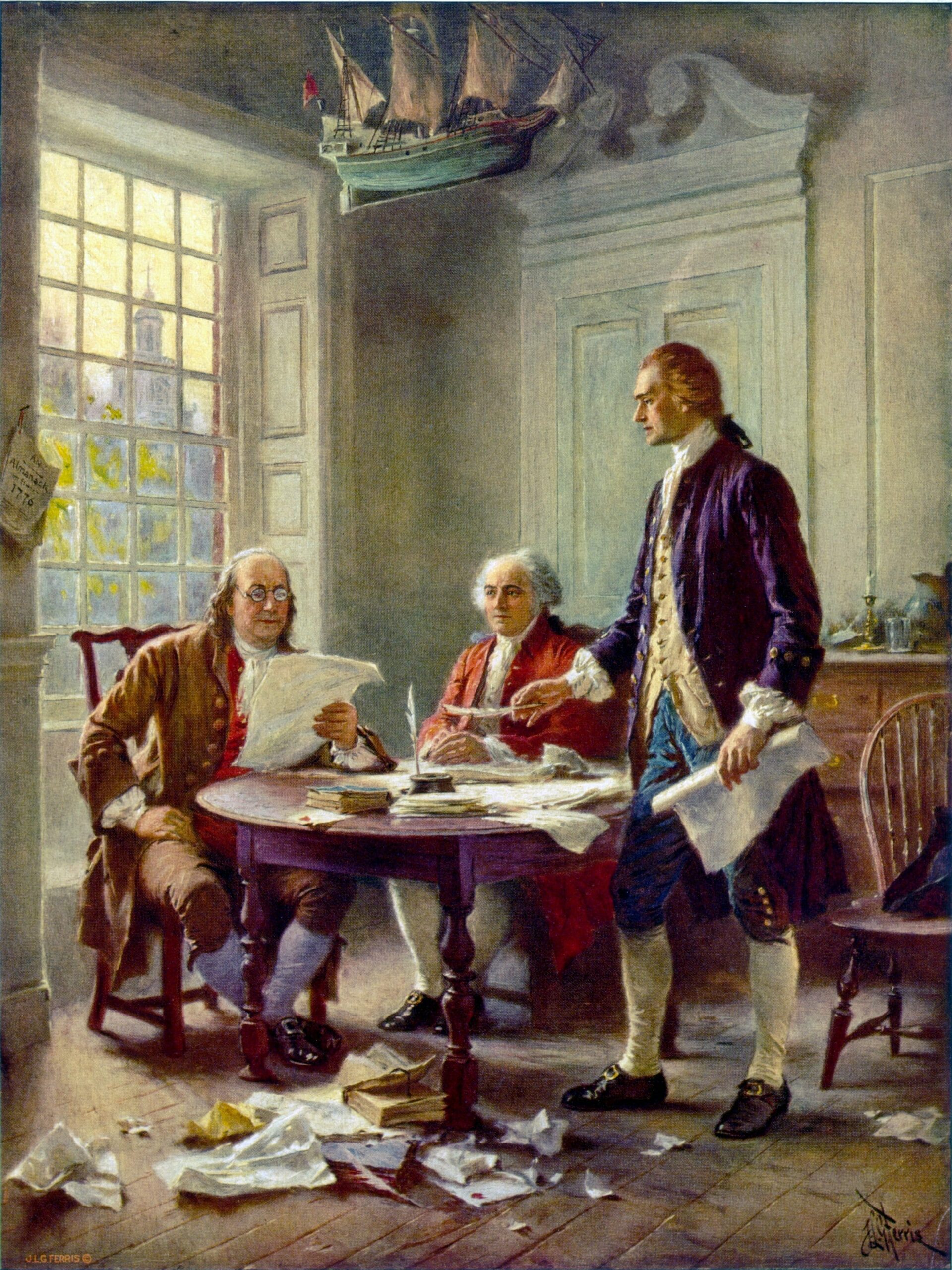

For several weeks, the Convention was at a standstill. The secrecy rule, as established in Act I, continued to prevent delegates from disclosing details of the proceedings. However, correspondence from early Act II illustrates delegates’ concerns. Some expressed doubts about the likelihood of reaching a resolution due to the diversity of opinions present, while others described the work as difficult and laborious. Many also reiterated their frustration at the slow pace of the proceedings.

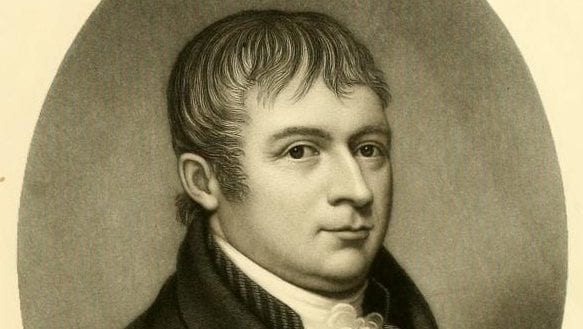

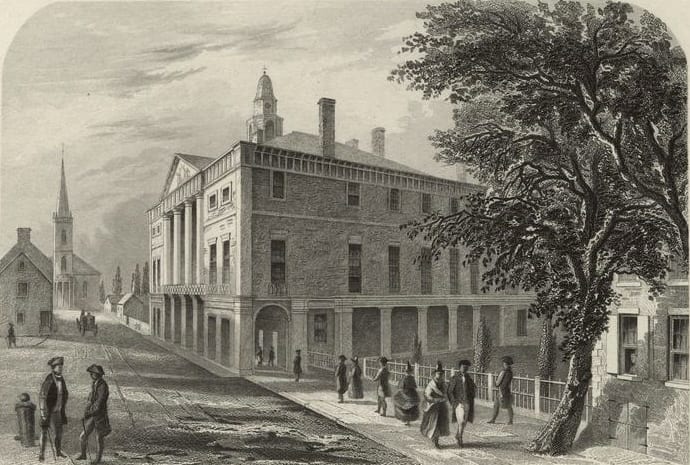

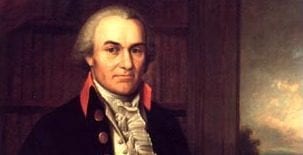

The Convention reached a breakthrough on June 30 when Oliver Ellsworth (1745–1807) of Connecticut introduced the Connecticut Compromise. This motion promoted the idea that the nation was both federal and national in character. The compromise proposed proportional representation in the lower House to reflect the will of the people, and equal representation of states in the upper House to secure state interests. Ellsworth’s proposal helped reconcile the divide between supporters of the Virginia and New Jersey plans by offering a new solution for delegates.

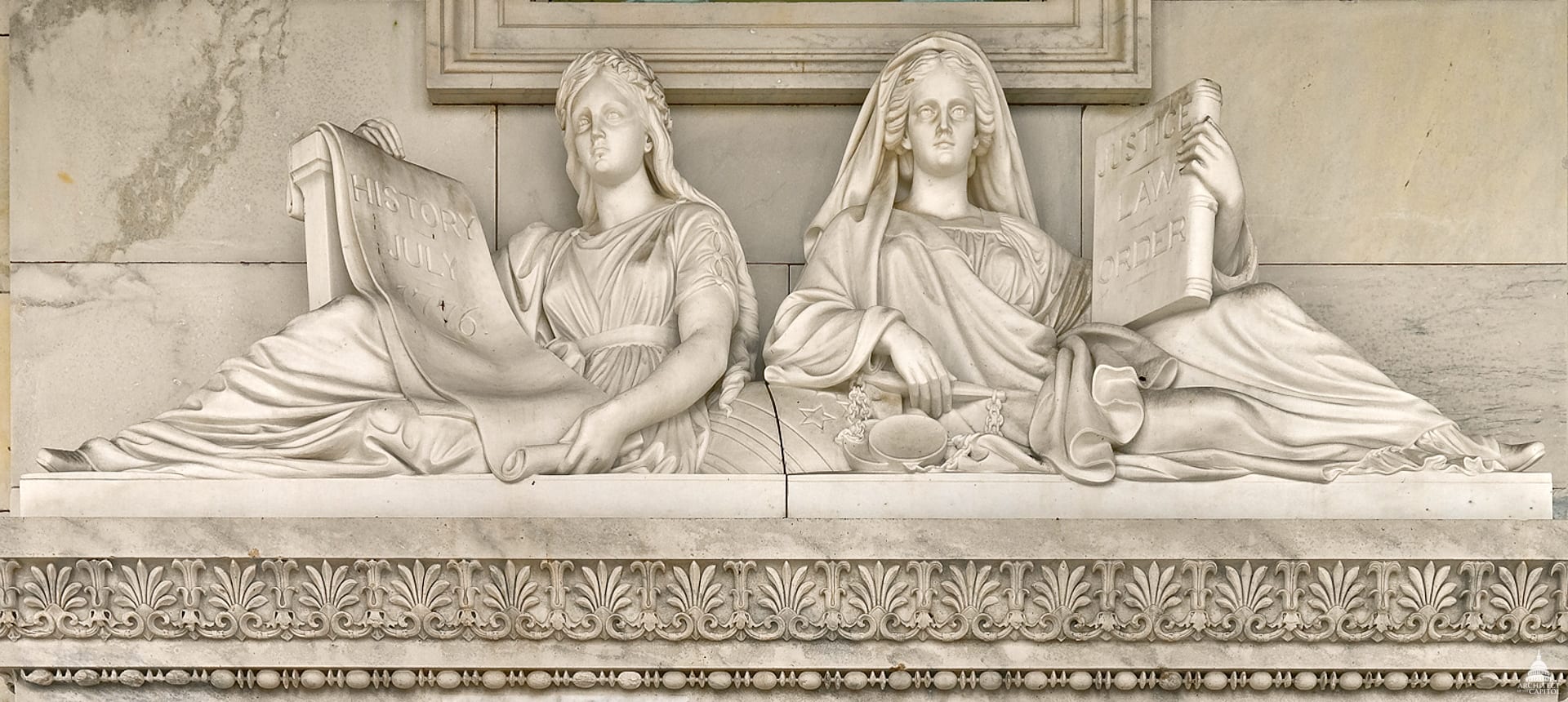

Ellsworth’s motion helped move the Convention forward by providing a new option for delegates and alleviating the weeks-long stalemate. To explore the impact of the proposed legislative structure on the nation, the Gerry Committee was formed, consisting of one delegate from each state in attendance. The committee presented its findings on July 5, leading to another series of debates that concluded on July 16 with the approval of the motion.

Act II letters provide a glimpse inside the closed deliberations of the Convention as delegates grappled with the direction of the national government while balancing their respective state interests. Despite making significant progress during June and July, much work remained for delegates as they continued to shape the nation’s path forward.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)