Introduction

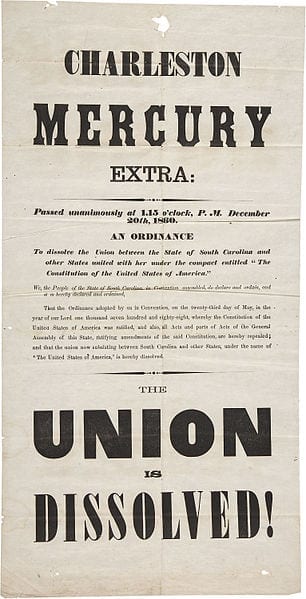

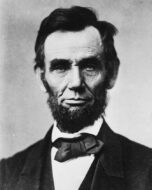

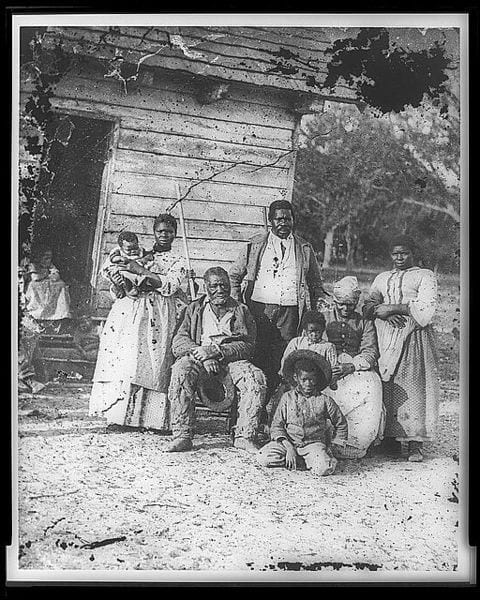

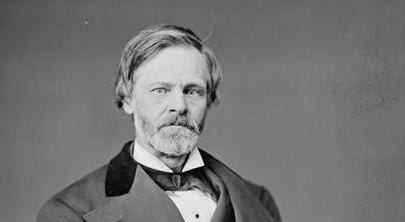

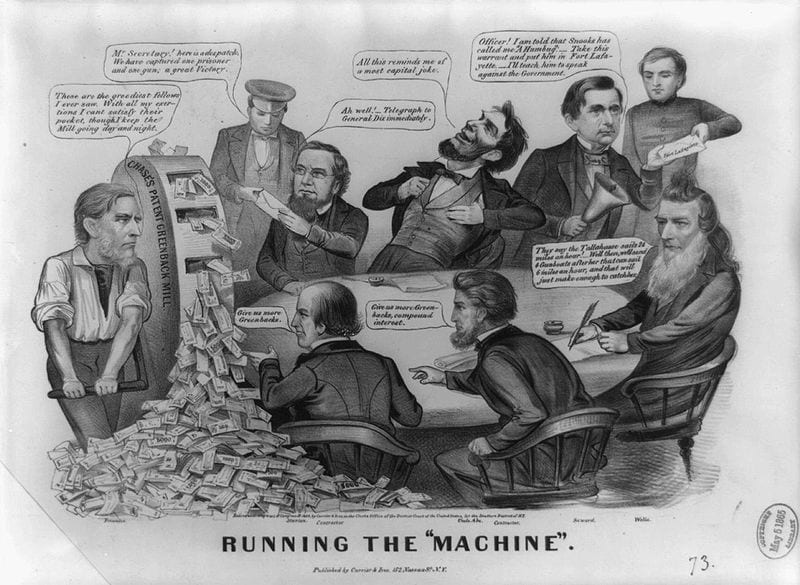

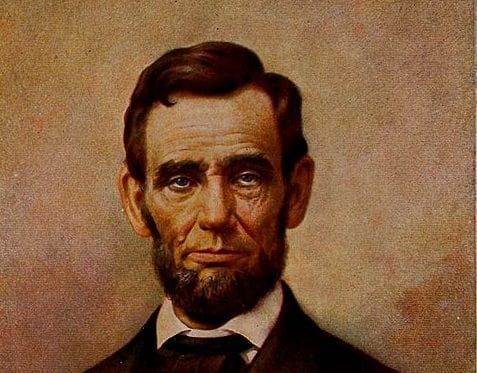

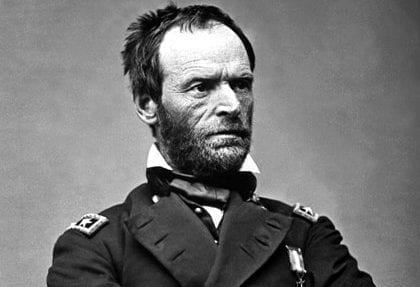

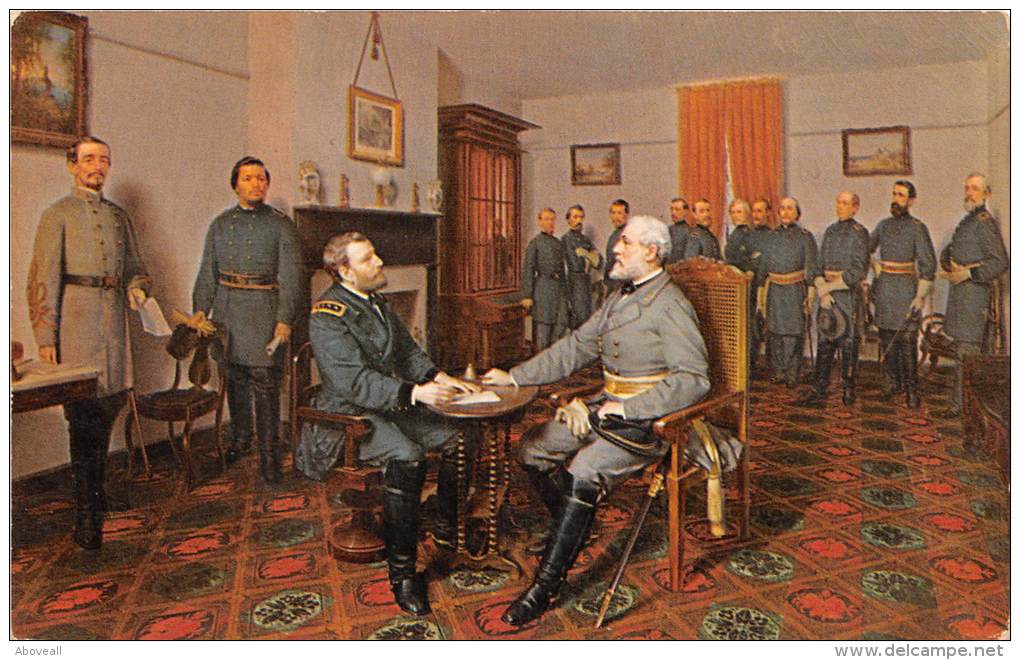

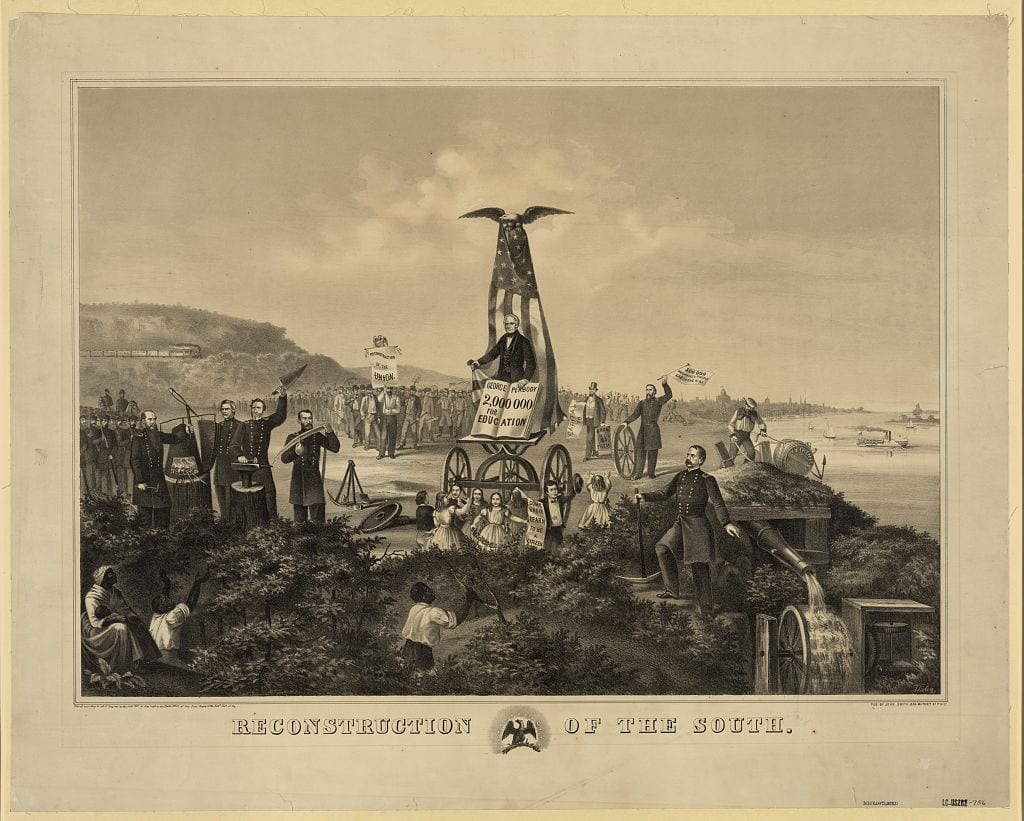

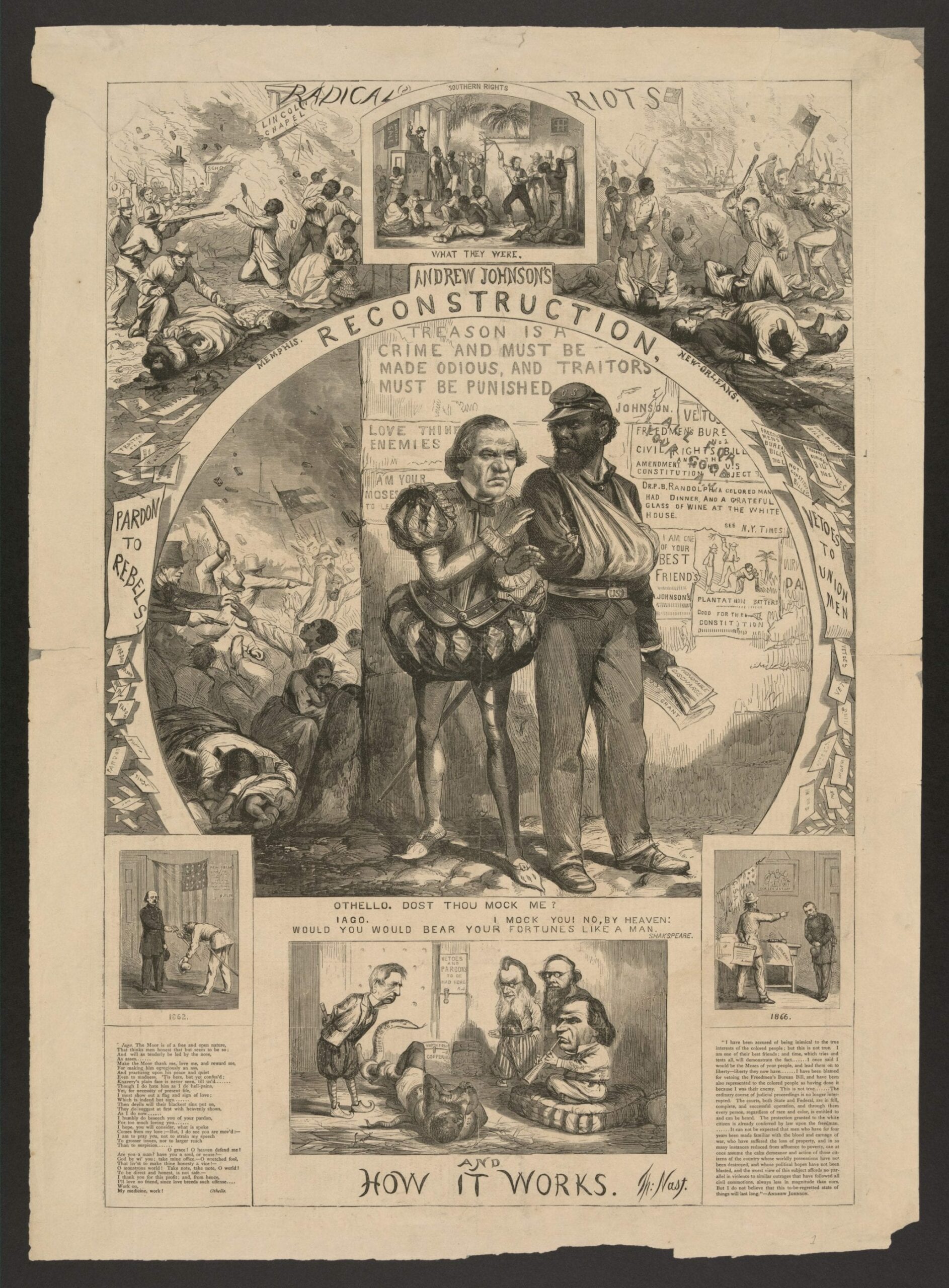

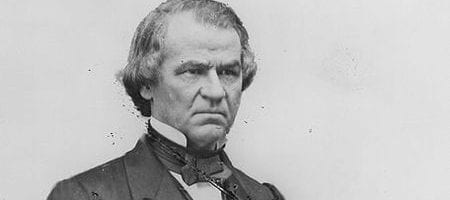

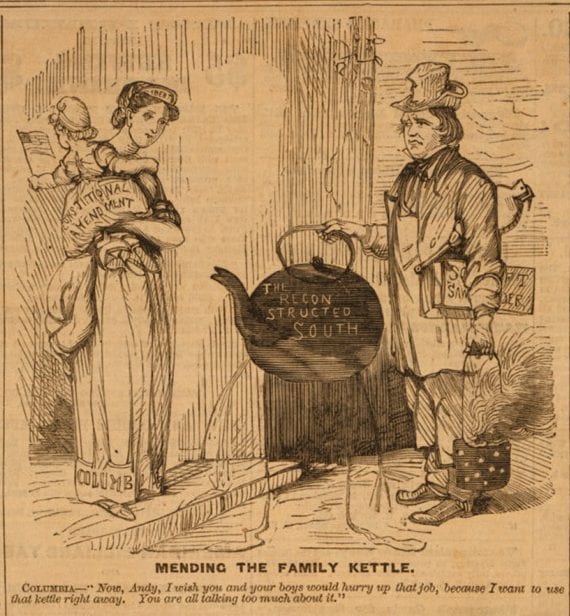

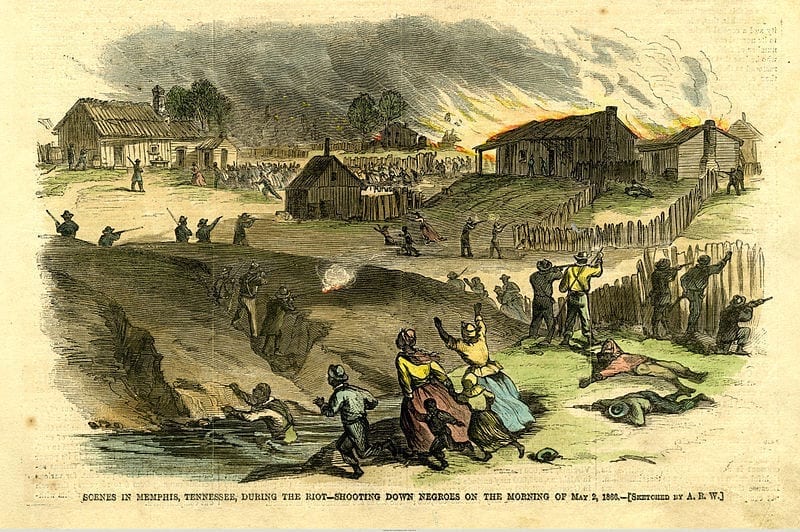

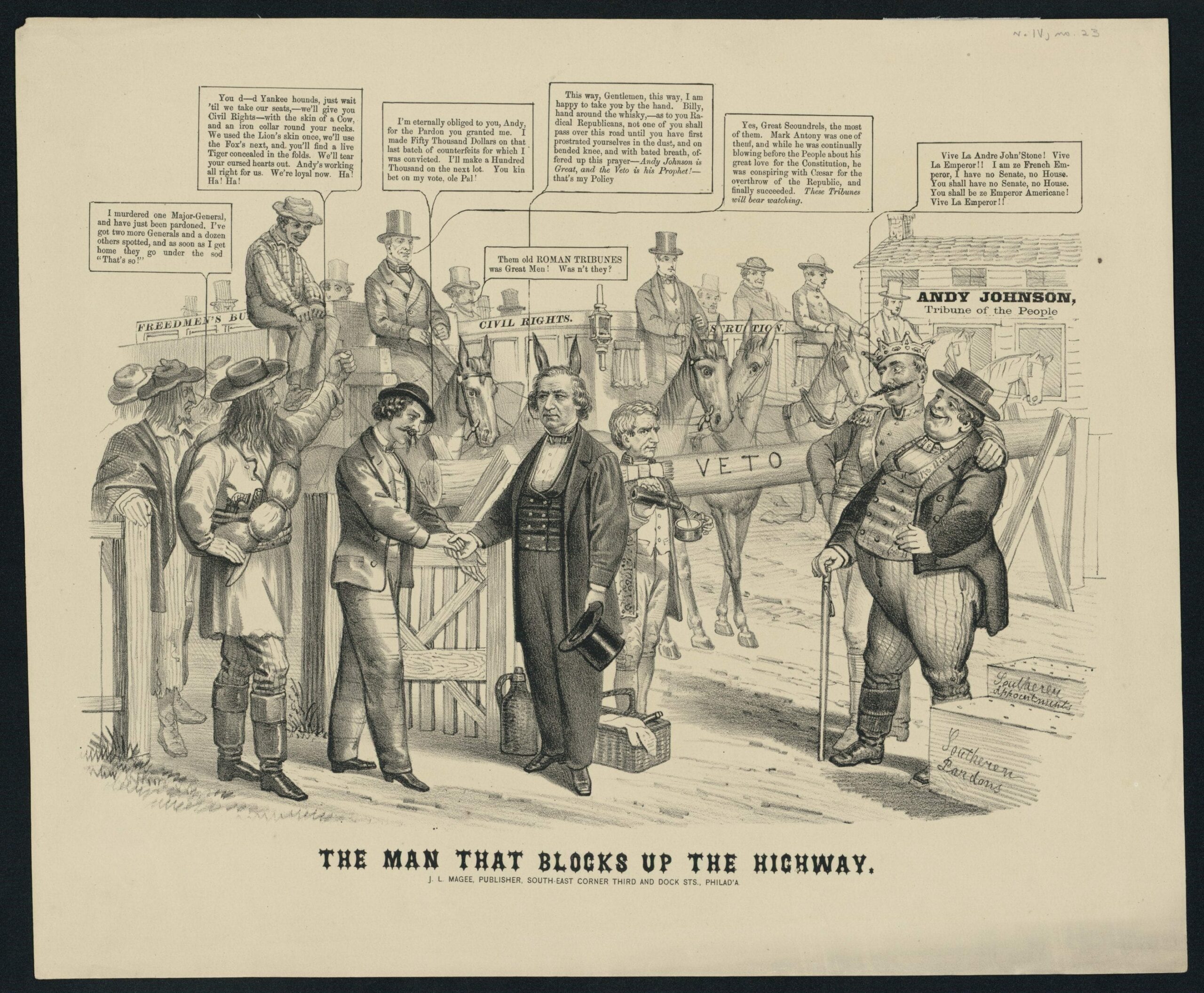

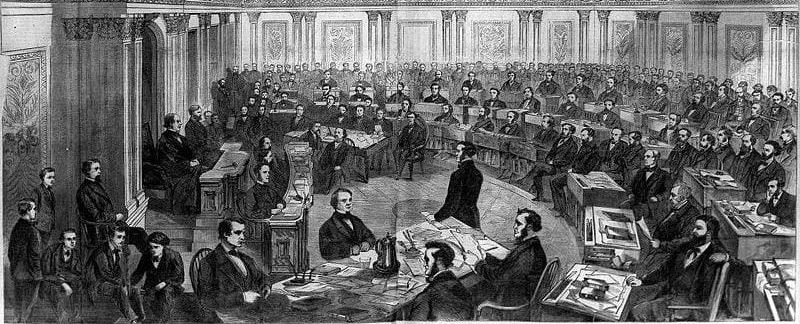

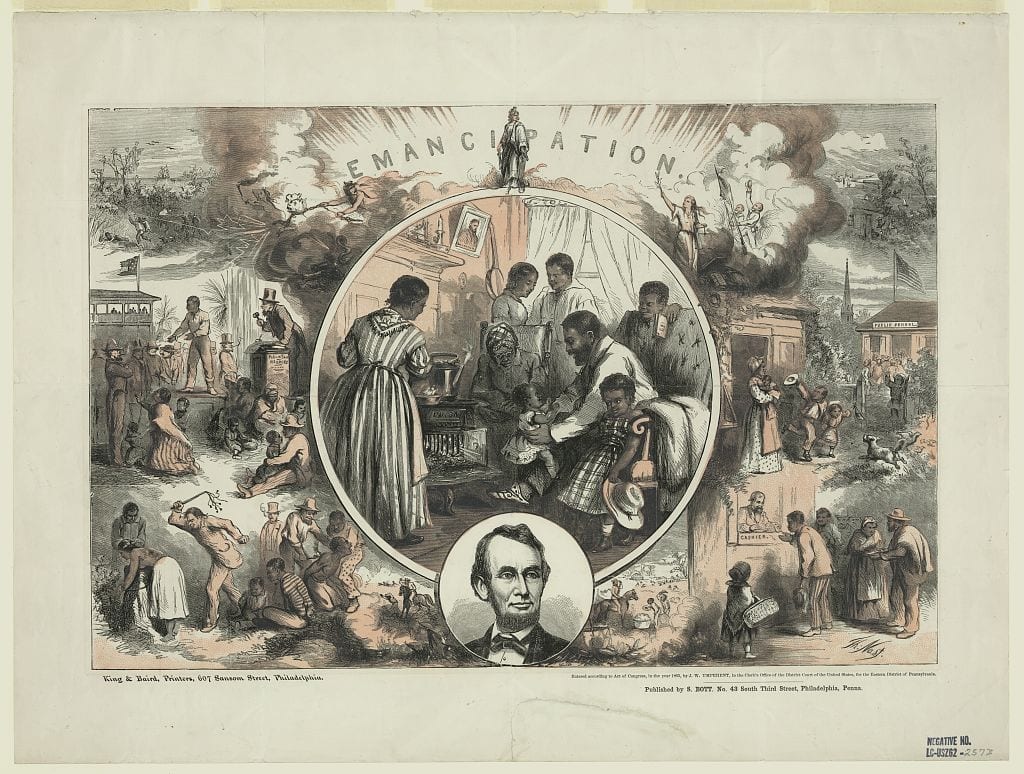

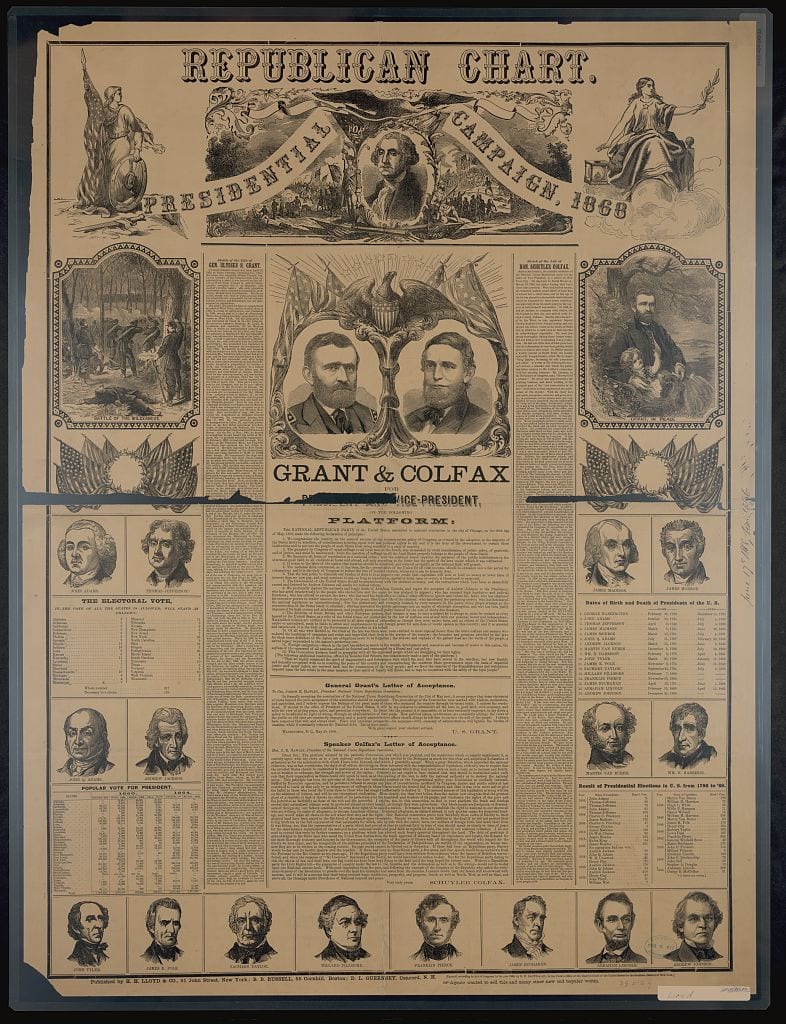

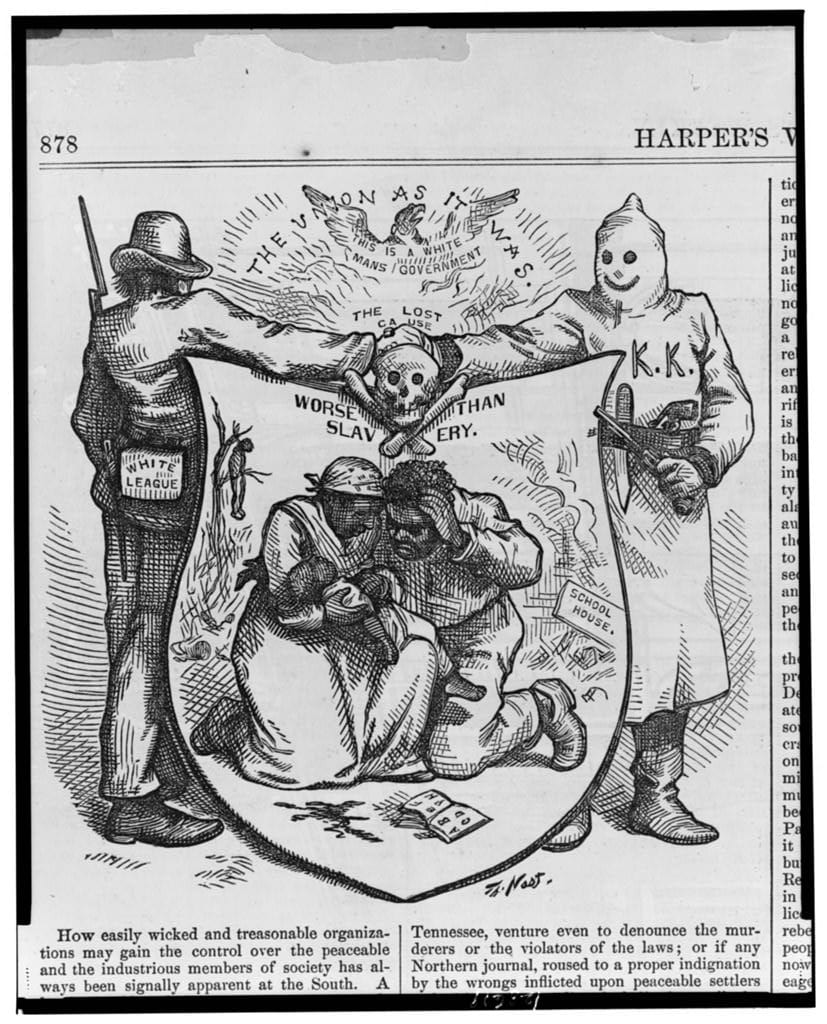

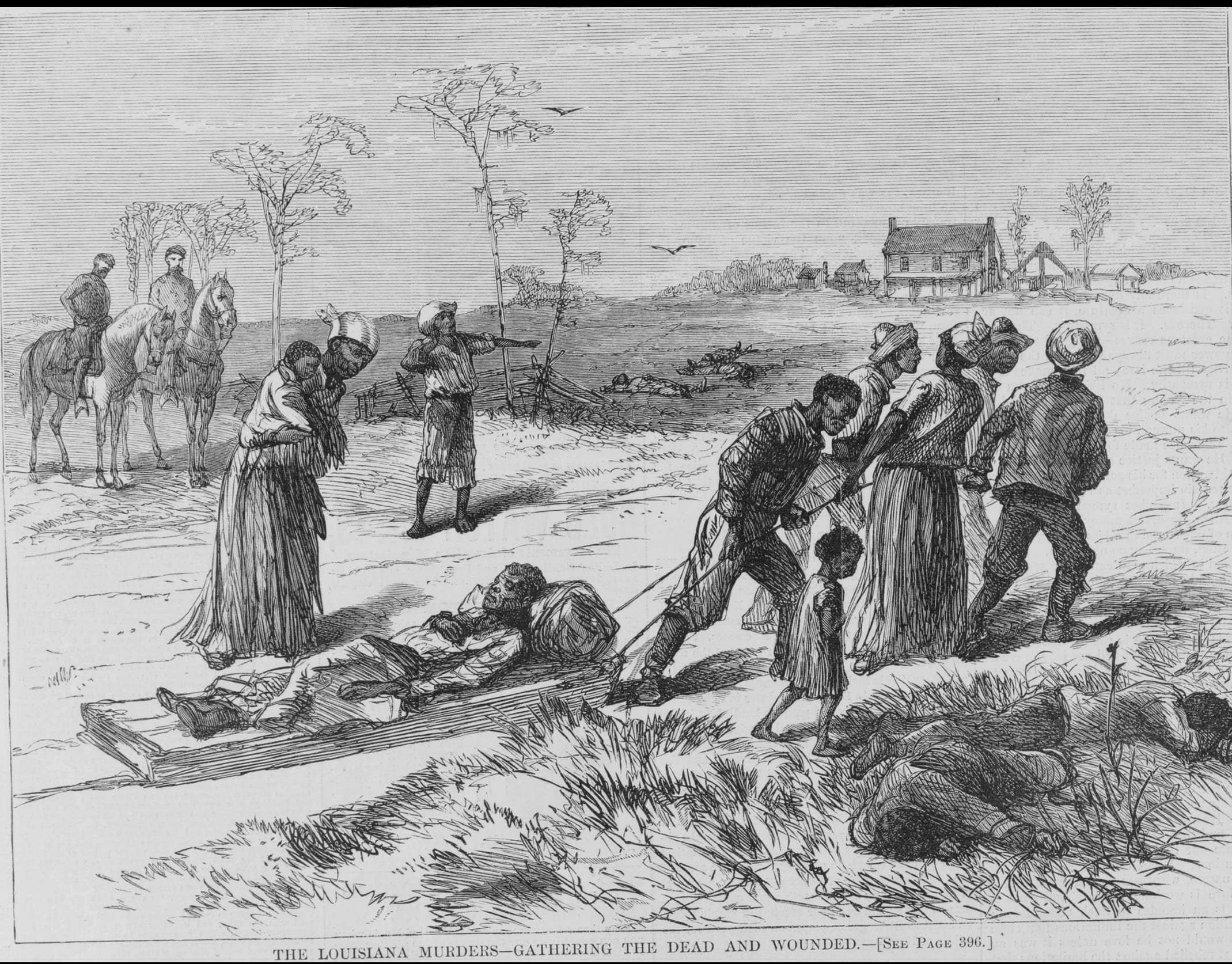

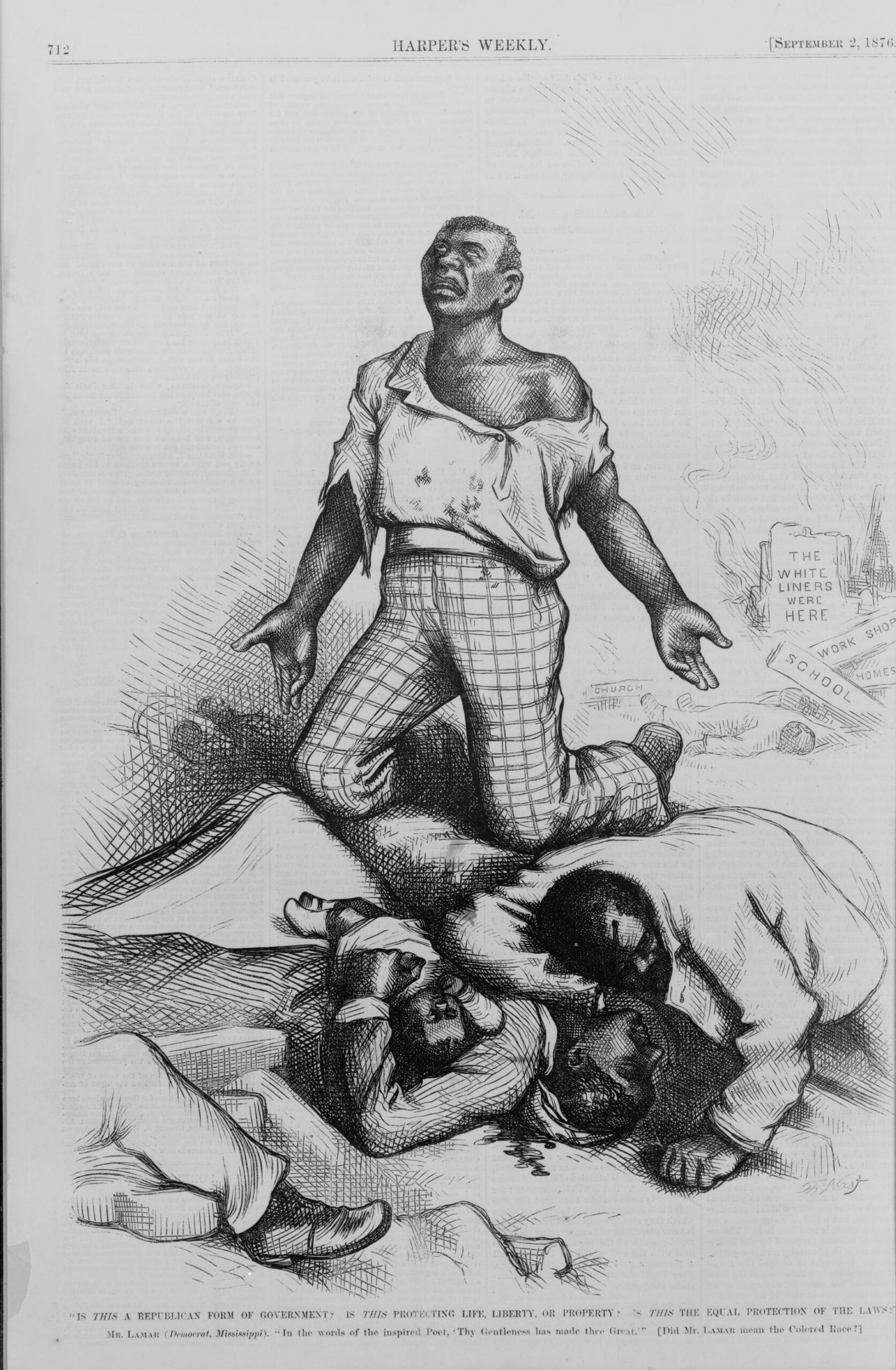

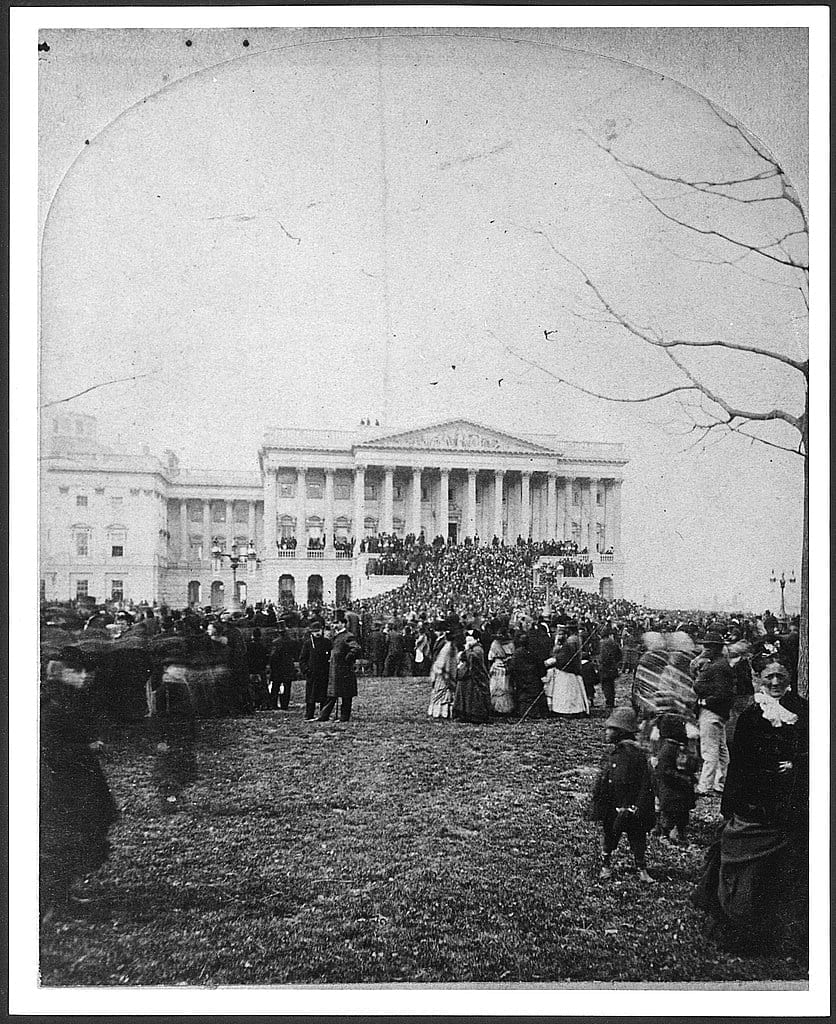

Reconstruction involved the twin goals of national reconciliation and emancipation for former slaves. As power was returned to restored Southern governments and as the Union army retreated, former rebels tended to rise to power under these restored governments. This threatened the already compromised safety and liberty of the freed slaves. The two goals of reconciliation and emancipation, it seems, could not be pursued to the same extent at the same time. The tension between the two can be seen in the words in and actions surrounding President Ulysses S. Grant’s annual address in 1871. On the one hand, Grant bemoaned “the condition of the southern states,” where “the old citizens of these states” did not tolerate “freedom of expression and ballot in those entertaining different political convictions.” Grant was pointing to his concerns about the Ku Klux Klan, a problem on which Congress had lately legislated.

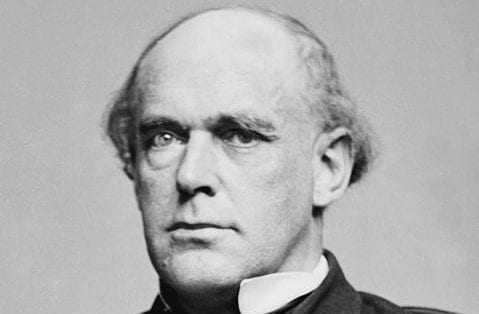

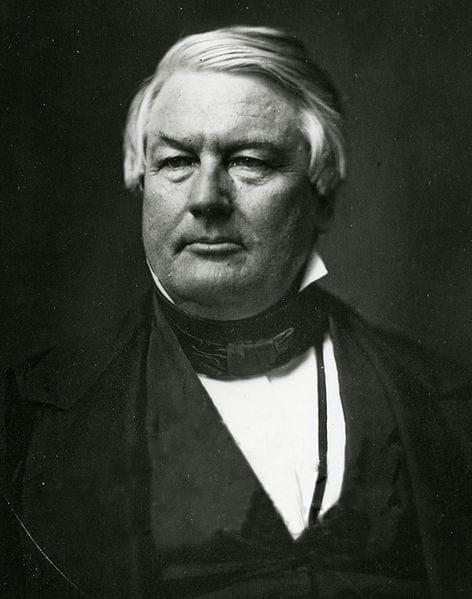

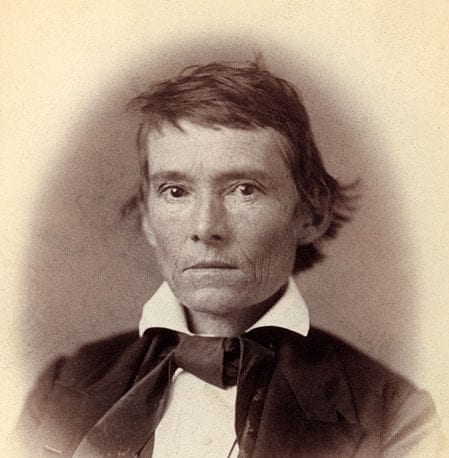

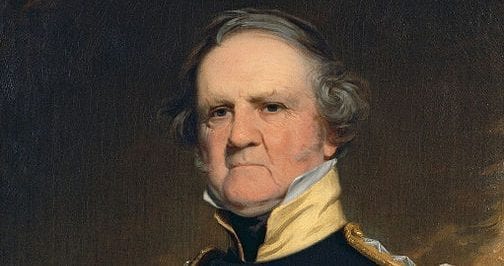

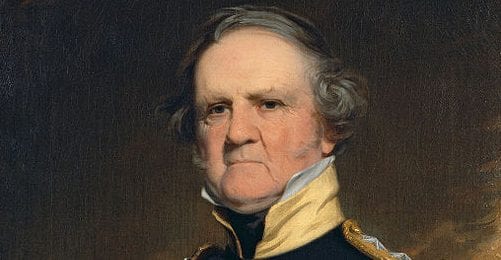

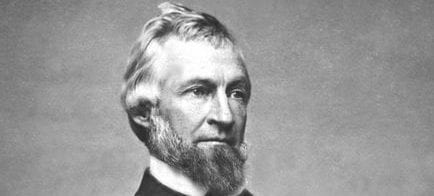

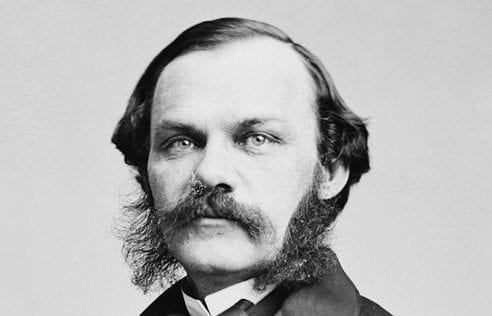

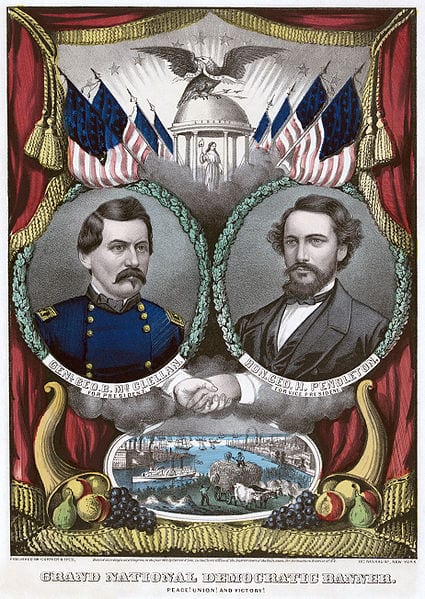

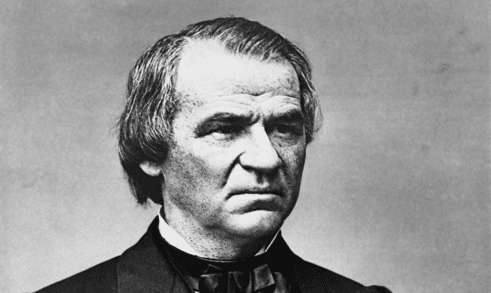

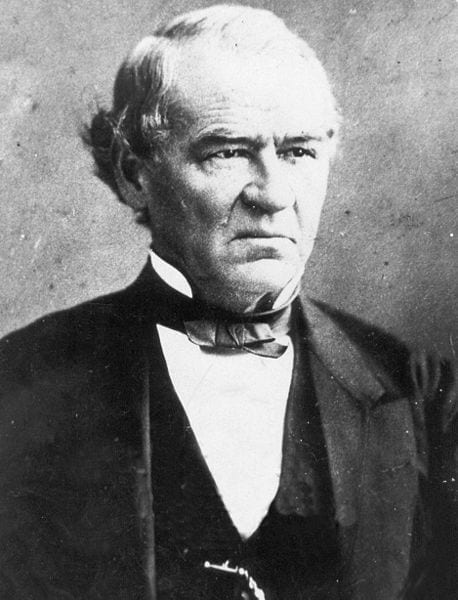

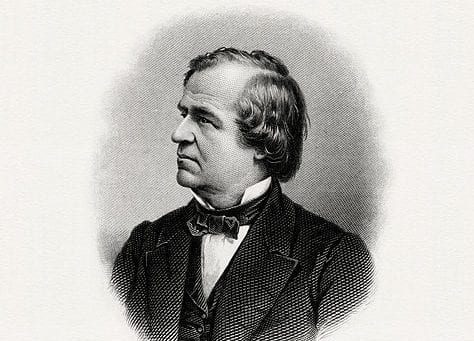

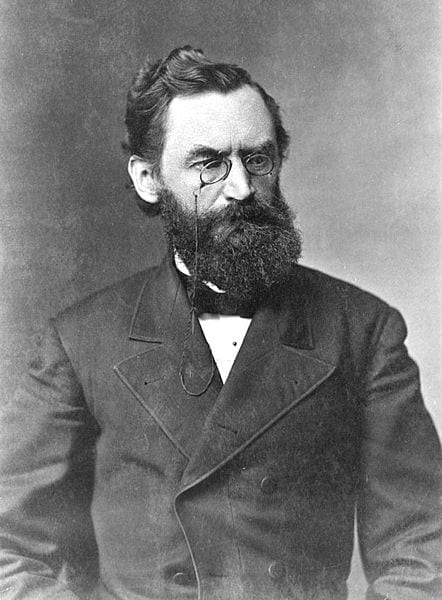

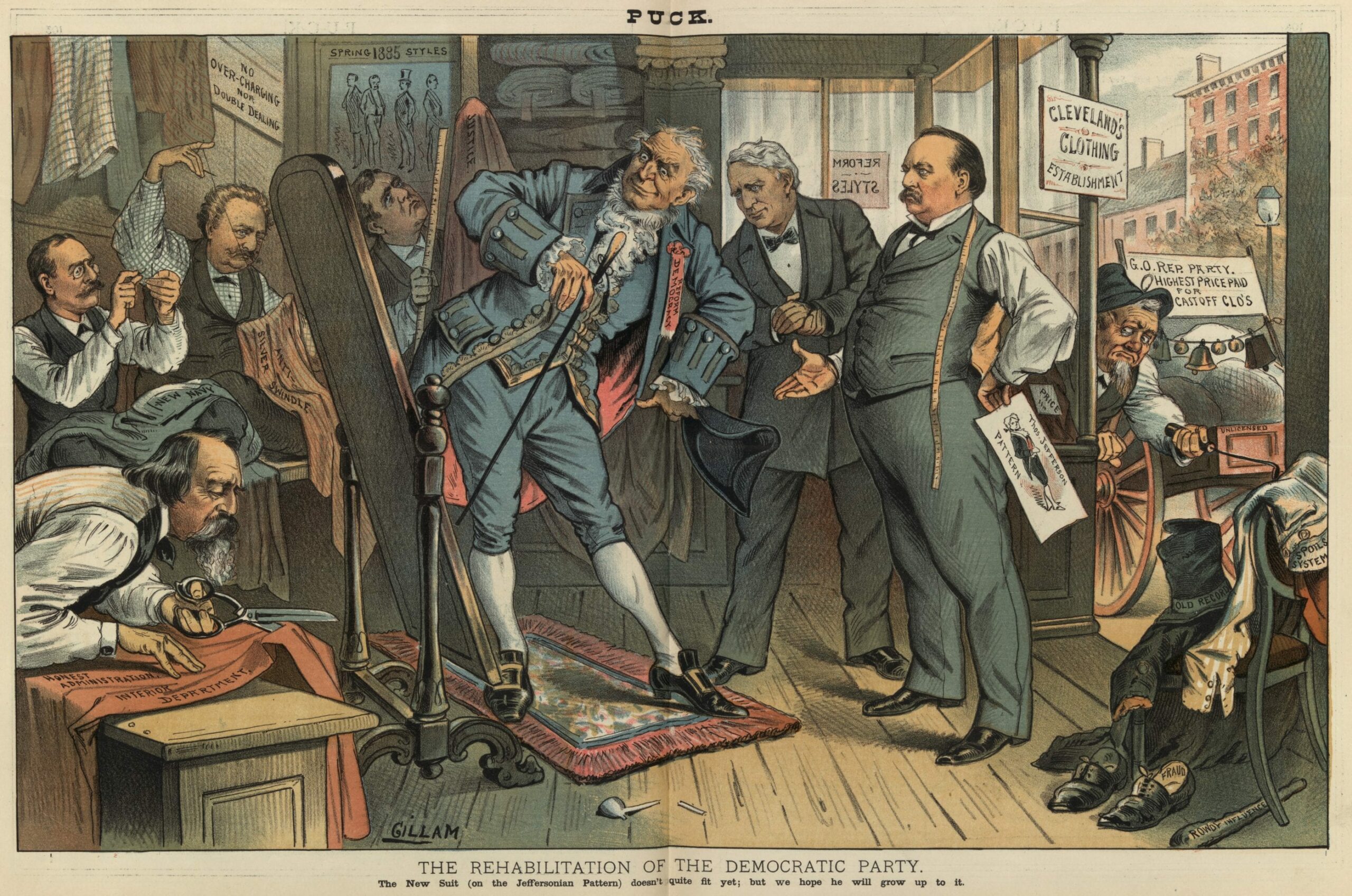

On the other hand, Grant requested that Congress remove prohibitions on office-holding for most former Confederates. Republican and Northern support for a vigorous policy protecting the freed slaves at the expense of reconciliation was waning. A vocal minority of Republicans blamed Grant for too vigorous an exercise of presidential power. These dissident Republicans, who had opposed the Enforcement Acts, eventually constituted their own party called the Liberal Republicans. They ran Horace Greeley as their presidential candidate in 1872 on a platform of conciliation with white Southerners and skepticism toward continued federal intervention to protect blacks. Senator Carl Schurz, who had earlier authored the “Report on the Condition of the South”, had, at that time, condemned Johnson’s policy of laxity toward restored Southern governments. Now he rose in favor of Liberal Republicanism, limits on federal power, and conciliation. The following excerpt is from a speech delivered by Schurz on the Senate floor, in which he advocates a generous amnesty for all who fought on behalf of the Confederacy.

Source: Speeches, Correspondences, and Political Papers of Carl Schurz, ed. Frederic Bancroft (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1913), Volume 2: 321–335, 337, 352–53. Available at https://goo.gl/JtnQvk.

. . . I beg leave to say that I am in favor of general, or as this word is considered more expressive, universal amnesty. . . .

In the course of this debate we have listened to some Senators, as they conjured up before our eyes once more all the horrors of the rebellion . . . how terrible its incidents were and how harrowing its consequences. . . . I will not combat the correctness of the picture; and yet, if I differ with the gentlemen who drew it, it is because, had the conception of the rebellion been still more wicked, had its incidents been still more terrible, its consequences still more harrowing, I could not permit myself to forget that in dealing with the question now before us we have to deal not alone with the past, but with the present and future interests of this Republic.

What do we want to accomplish as good citizens and patriots? Do we mean only to inflict upon late rebels pain, degradation, mortification, annoyance, for its own sake . . . ? Certainly such a spirit could not by any possibility animate high-minded men. I presume, therefore, that those who still favor the continuance of some of the disabilities imposed by the [14th] amendment,1 do so because they have some higher object of public usefulness in view . . . to justify, in their minds at least, the denial of rights to others which we ourselves enjoy.

What can those objects of public usefulness be? Let me assume that, if we differ as to the means to be employed, we are agreed as to the supreme end and aim to be reached. That end and aim of our endeavors can be no other than to secure to all the States the blessings of good and free government and the highest degree of prosperity and well-being they can attain, and to revive in all citizens of this Republic that love for the Union and its institutions, and that inspiring consciousness of a common nationality, which, after all, must bind all Americans together.

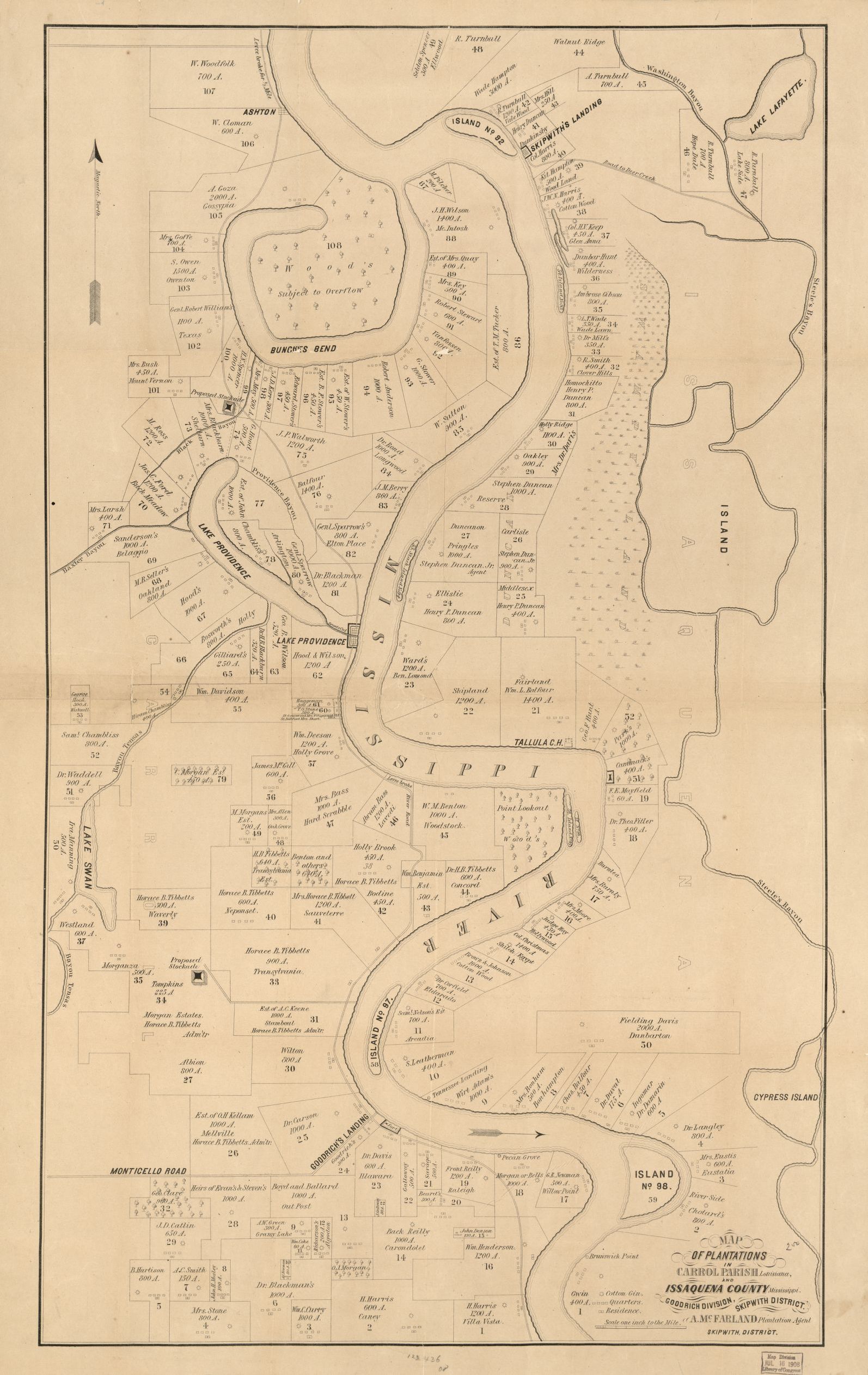

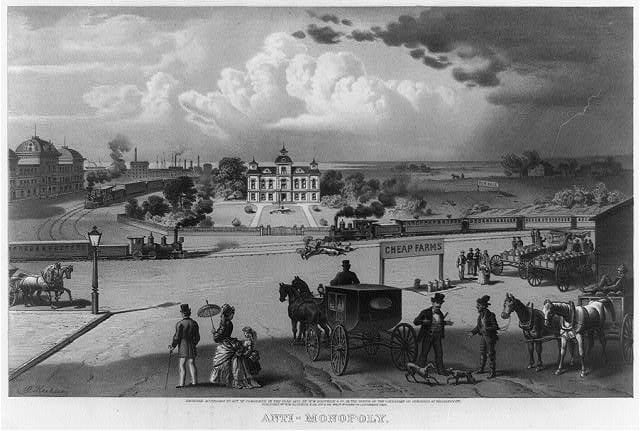

What are the best means for the attainment of that end? . . . Certainly all will agree that this end is far from having been attained so far. Look at the Southern States as they stand before us today. Some are in a condition bordering upon anarchy, not only on account of the social disorders which are occurring there, or the inefficiency of their local governments in securing the enforcement of the laws; but you will find in many of them fearful corruption pervading the whole political organization; a combination of rascality and ignorance wielding official power; their finances deranged by profligate practices; their credit ruined; bankruptcy staring them in the face; their industries staggering under a fearful load of taxation; their property-holders and capitalists paralyzed by a feeling of insecurity and distrust almost amounting to despair. . . .

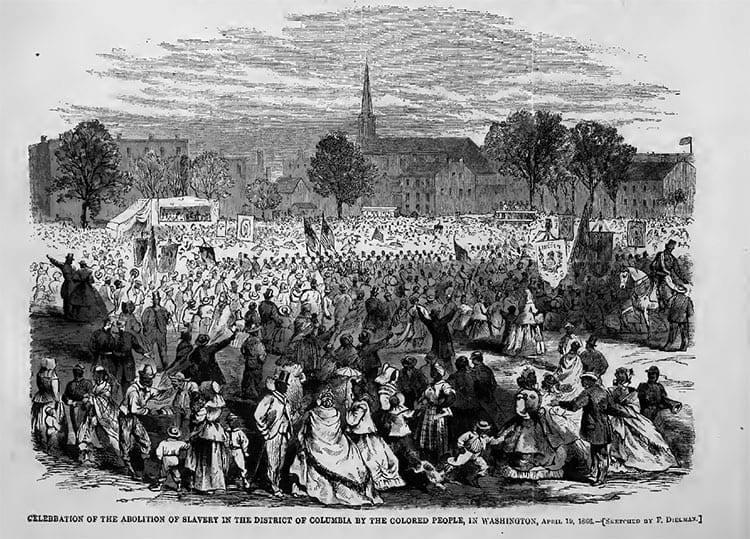

What are the causes that have contributed to bring about this distressing condition? I admit that great civil wars resulting in such vast social transformations as the sudden abolition of slavery are calculated to produce similar results; but it might be presumed that a recuperative power such as this country possesses might during the time which has elapsed since the close of the war at least have very materially alleviated many of the consequences of that revulsion, had a wise policy been followed.

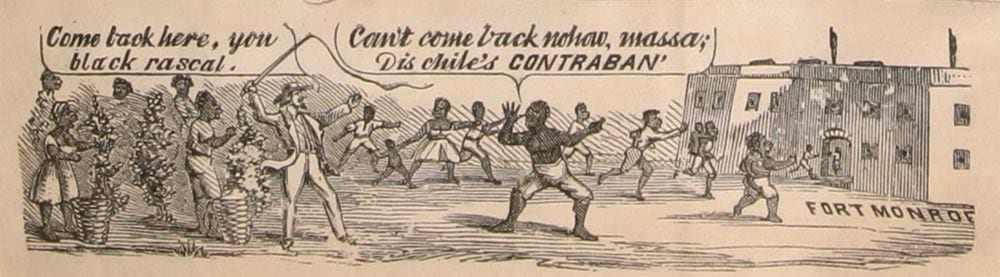

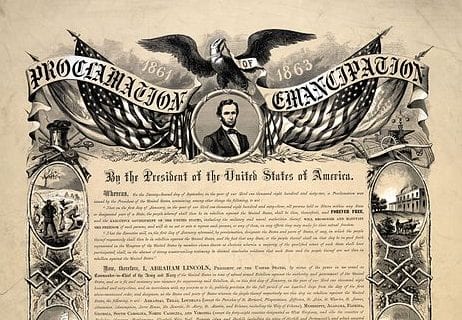

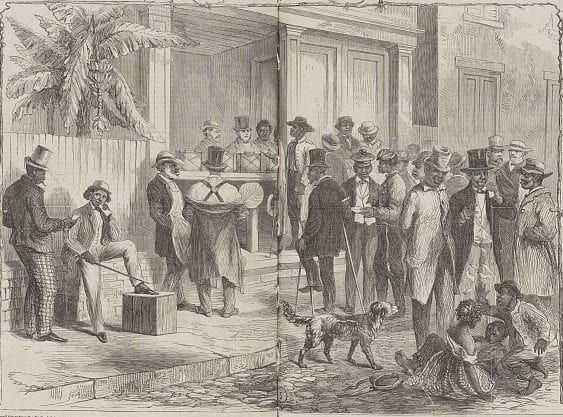

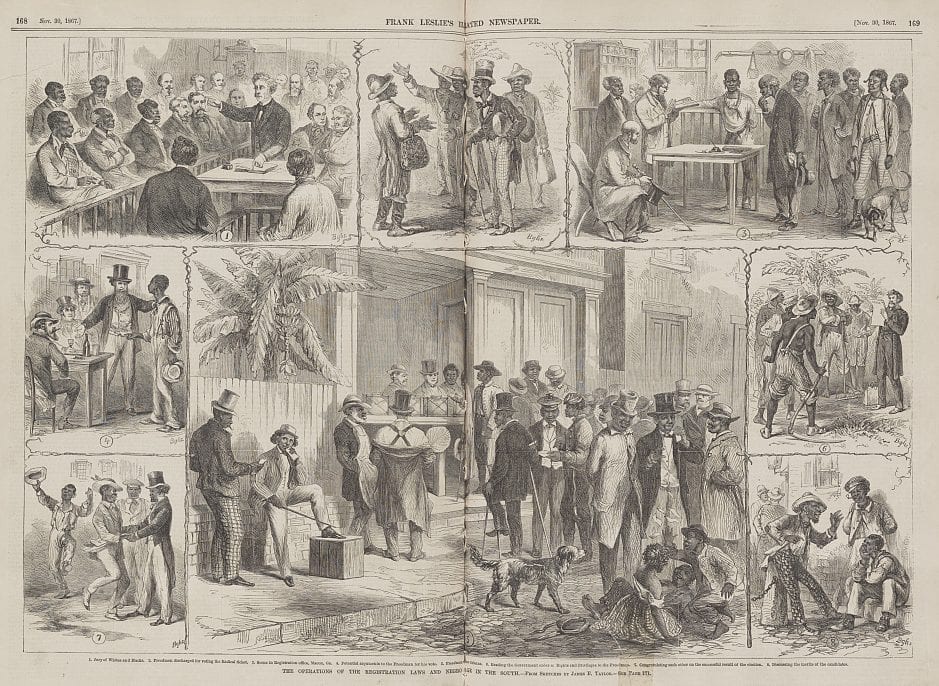

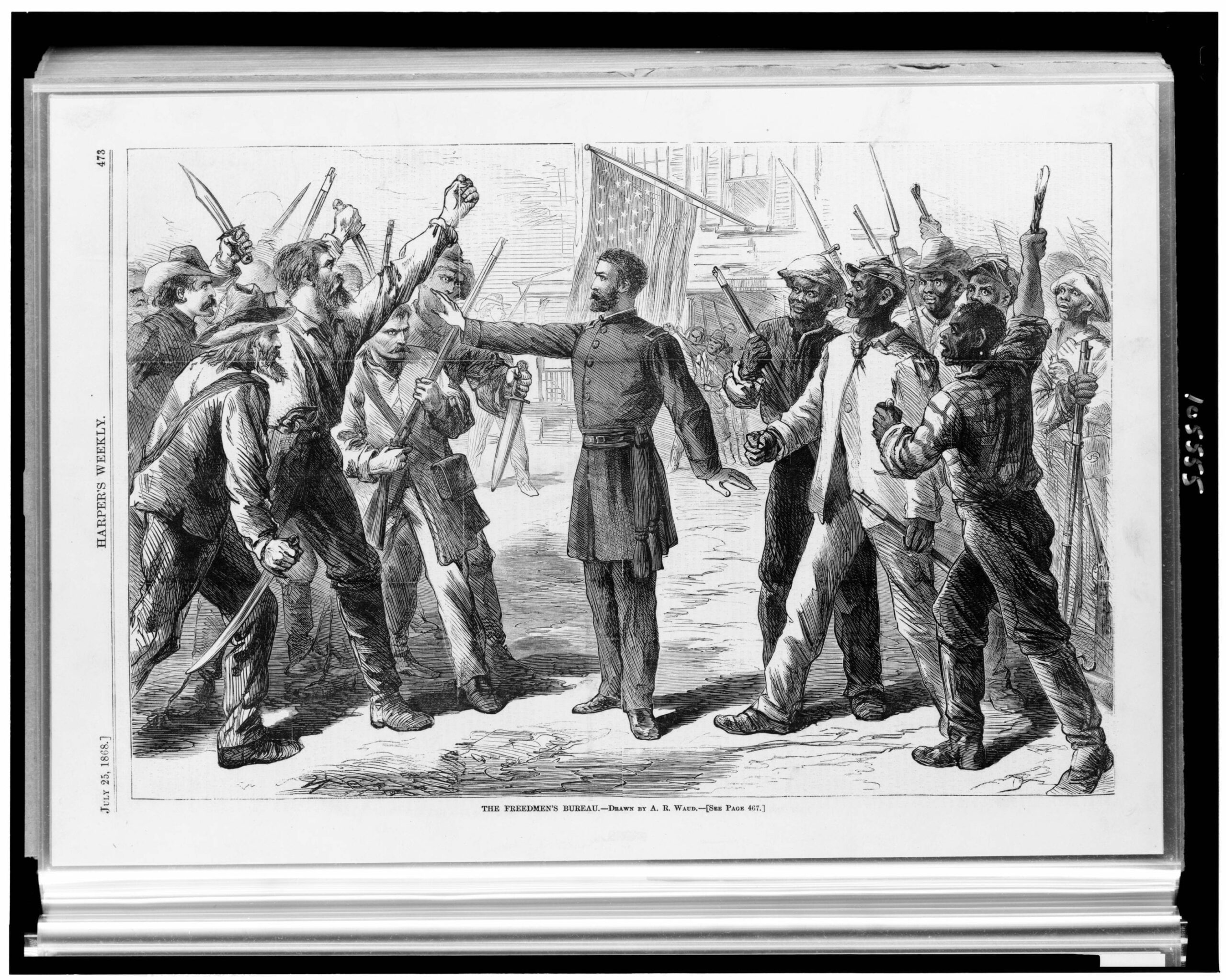

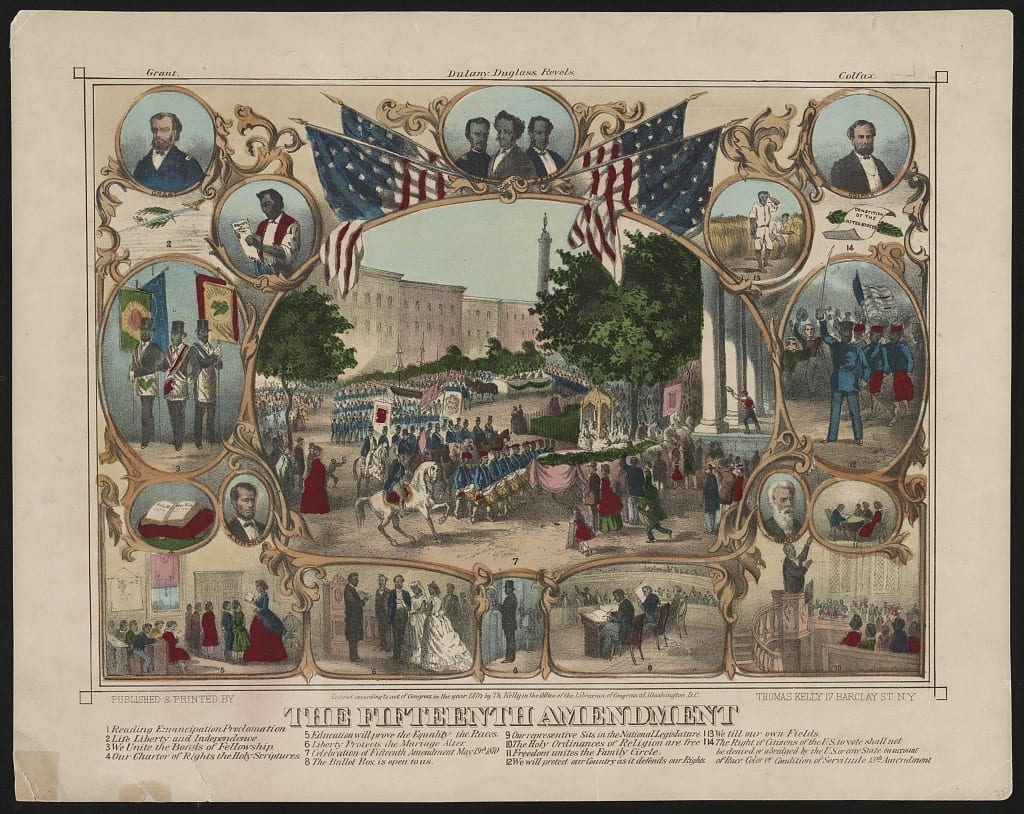

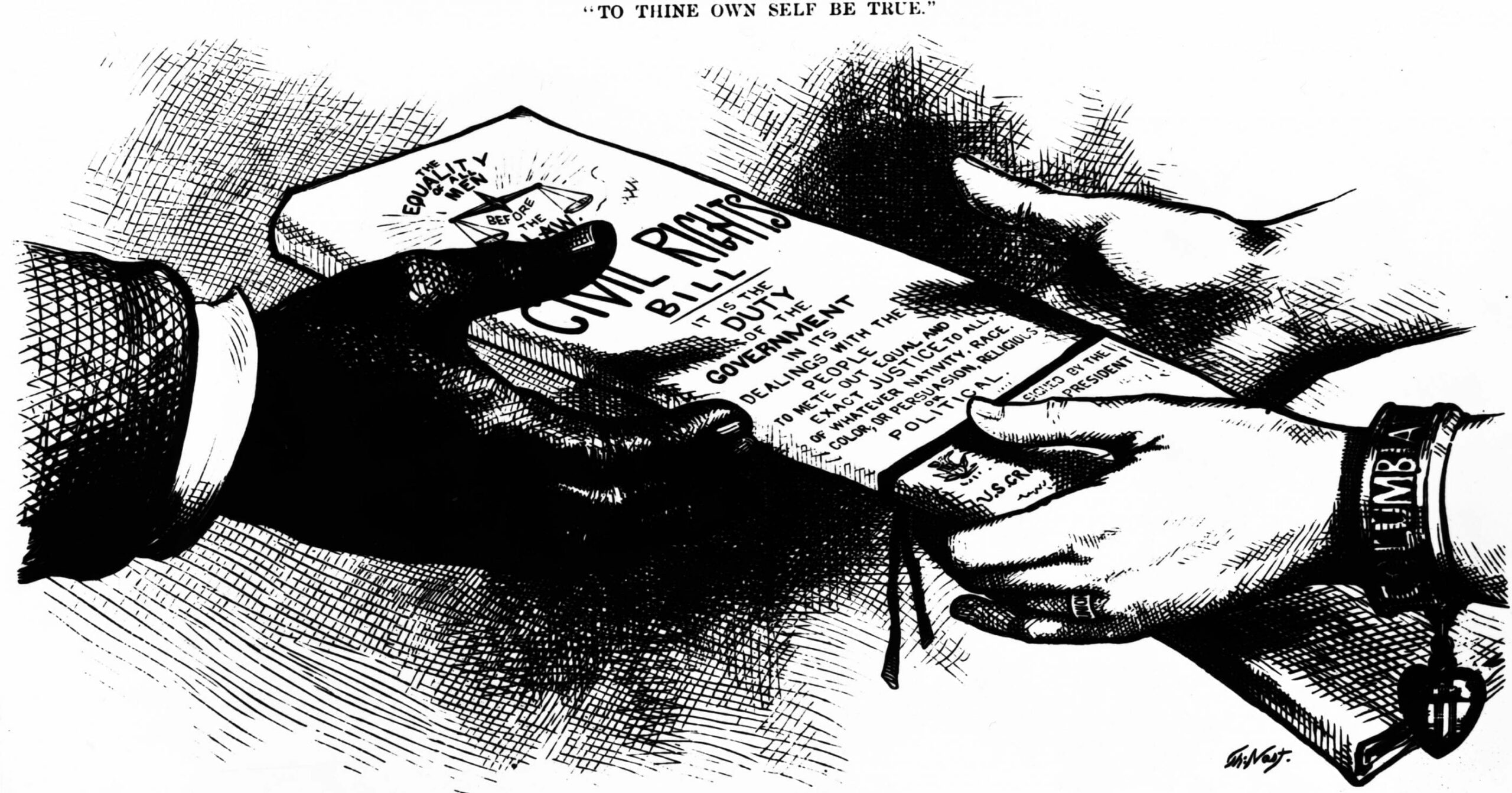

Was the policy we followed wise? Was it calculated to promote the great purposes we are endeavoring to serve? Let us see. At the close of the war we had to establish and secure free labor and the rights of the emancipated class. To that end we had to disarm those who could have prevented this, and we had to give the power of self-protection to those who needed it. For this reason temporary restrictions were imposed upon the late rebels, and we gave the right of suffrage to the colored people. Until the latter were enabled to protect themselves, political disabilities even more extensive than those which now exist, rested upon the plea of eminent political necessity. I would be the last man to conceal that I thought so then, and I think now there was very good reason for it.

But, sir, when the enfranchisement of the colored people was secured, when they had obtained the political means to protect themselves, then another problem began to loom up. It was not only to find new guaranties for the rights of the colored people, but it was to secure good and honest government for all. Let us not underestimate the importance of that problem, for in a great measure it includes the solution of the other. Certainly, nothing could have been better calculated to remove the prevailing discontent concerning the changes that had taken place, and to reconcile men’s minds to the new order of things, than the tangible proof that that new order of things was practically working well. . . . And, on the other hand, nothing could have been more calculated to impede a general, hearty and honest acceptance of the new order of things by the late rebel population than just those failures of public administration which involve the people in material embarrassments and so seriously disturb their comfort. . . .

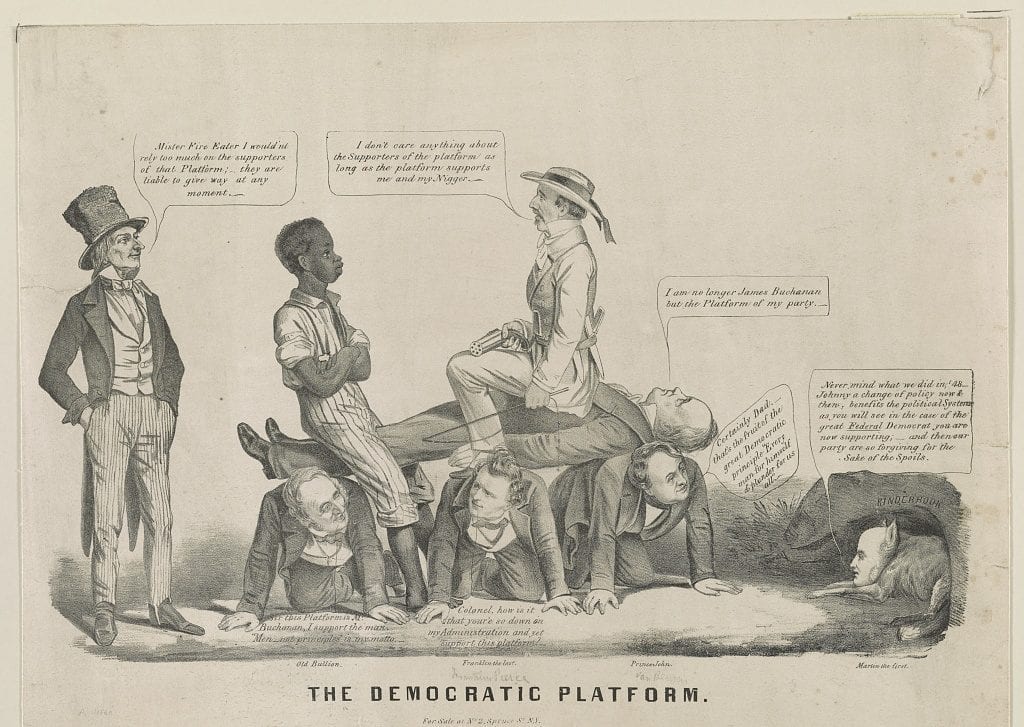

. . . [W]hat happened in the South? It is a well-known fact that the more intelligent classes of Southern society almost uniformly identified themselves with the rebellion; and by our system of political disabilities just those classes were excluded from the management of political affairs. That they could not be trusted with the business of introducing into living practice the results of the war, to establish true free labor and to protect the rights of the emancipated slaves, is true; I willingly admit it. But when those results and rights were constitutionally secured there were other things to be done. . . . But just then a large portion of that intelligence and experience was excluded from the management of public affairs by political disabilities, and the controlling power in those States rested in a great measure in the hands of those who had but recently been slaves and just emerged from that condition, and in the hands of others who had sometimes honestly, sometimes by crooked means and for sinister purposes, found a way to their confidence.2

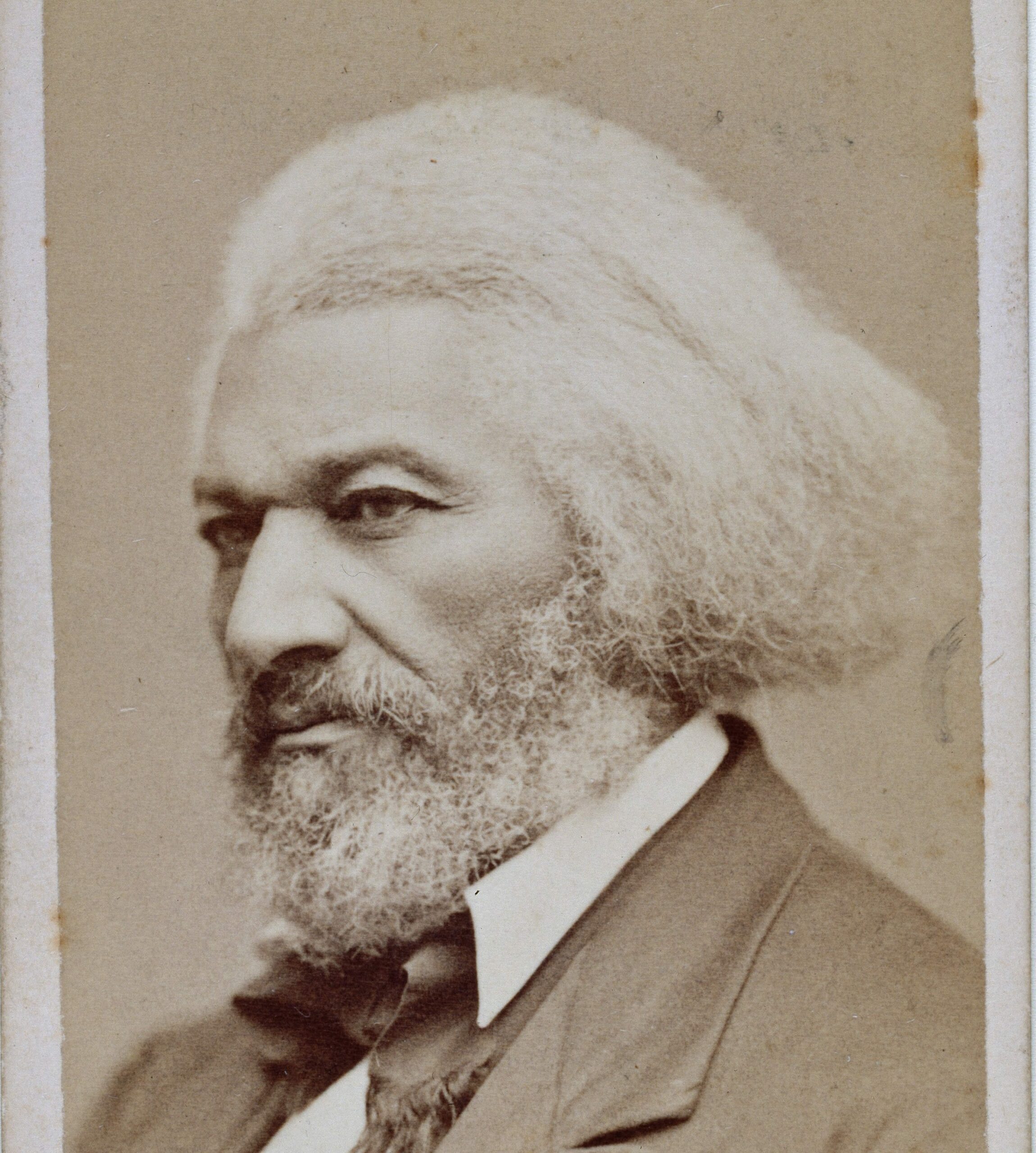

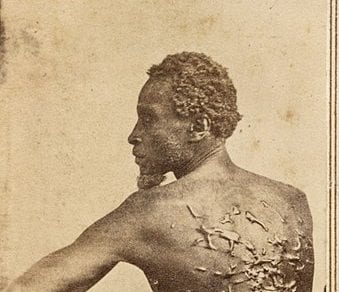

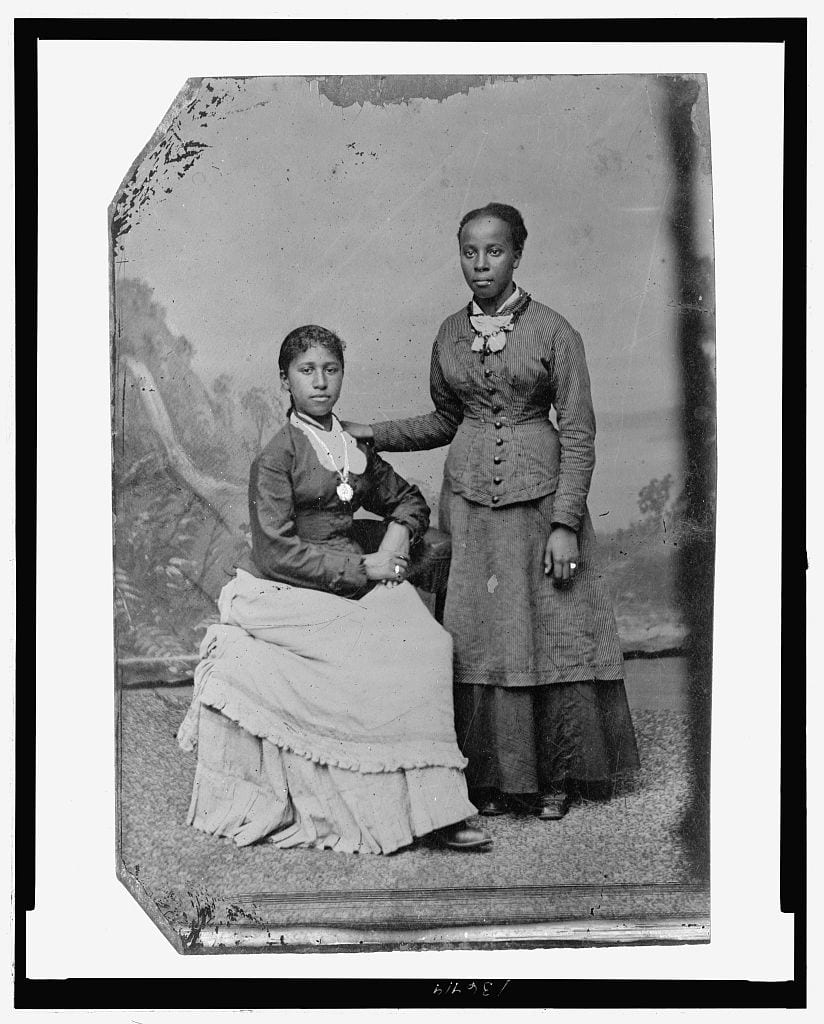

This was the state of things as it then existed. Nothing could be farther from my intention than to cast a slur upon the character of the colored people of the South. . . . Look into the history of the world, and you will find that almost every similar act of emancipation, the abolition of serfdom, for instance, was uniformly accompanied by atrocious outbreaks of a revengeful spirit; by the slaughters of nobles and their families, illumined by the glare of their burning castles. Not so here. . . . [S]carcely a single act of revenge for injuries suffered or for misery endured has darkened the record of the emancipated bondmen of America. And thus their example stands unrivalled in history, and they as well as the whole American people, may well be proud of it. Certainly, the Southern people should never cease to remember and appreciate it.

But while the colored people of the South thus earned our admiration and gratitude, I ask you in all candor, could they be reasonably expected, when, just after having emerged from a condition of slavery, they were invested with political rights and privileges, to step into the political arena as men armed with the intelligence and experience necessary for the management of public affairs and for the solution of problems made doubly intricate by the disaster which had desolated the Southern country? . . . That as a class they were ignorant and inexperienced and lacked a just conception of public interests, was certainly not their fault. . . . But the stubborn fact remains that they were ignorant and inexperienced; that the public business was an unknown world to them, and that in spite of the best intentions they were easily misled, not infrequently by the most reckless rascality which had found a way to their confidence. Thus their political rights and privileges were undoubtedly well calculated, and even necessary, to protect their rights as free laborers and citizens; but they were not well calculated to secure a successful administration of other public interests.

I do not blame the colored people for it; still less do I say that for this reason their political rights and privileges should have been denied them. Nay, sir, I deemed it necessary then, and I now reaffirm that opinion, that they should possess those rights and privileges for the permanent establishment of the logical and legitimate results of the war and the protection of their new position in society. But, while never losing sight of this necessity, I do say that the inevitable consequence of the admission of so large an uneducated and inexperienced class to political power, as to the probable mismanagement of the material interests of the social body, should at least have been mitigated by a counterbalancing policy. . . . [W]hen universal suffrage was granted to secure the equal rights of all, universal amnesty ought to have been granted to make all the resources of political intelligence and experience available for the promotion of the welfare of all.

But what did we do? To the uneducated and inexperienced classes – uneducated and inexperienced, I repeat, entirely without their fault – we opened the road to power; and, at the same time, we condemned a large proportion of the intelligence of those States, of the property-holding, the industrial, the professional, the tax-paying interest, to a worse than passive attitude. We made it, as it were, easy for rascals who had gone South in quest of profitable adventure to gain the control of masses so easily misled, by permitting them to appear as the exponents and representatives of the National power and of our policy; and at the same time we branded a large number of men of intelligence, and many of them of personal integrity, whose material interests were so largely involved in honest government, and many of whom would have cooperated in managing the public business with care and foresight – we branded them, I say, as outcasts, telling them that they ought not to be suffered to exercise any influence upon the management of the public business, and that it would be unwarrantable presumption in them to attempt it.

I ask you, sir, could such things fail to contribute to the results we read to-day in the political corruption and demoralization, and in the financial ruin of some of the Southern States? These results are now before us. The mistaken policy may have been pardonable when these consequences were still a matter of conjecture and speculation; but what excuse have we now for continuing it when those results are clear before our eyes, beyond the reach of contradiction?

These considerations would seem to apply more particularly to those Southern States in which the colored element constitutes a very large proportion of the voting body. There is another which applies to all. . . .

The introduction of the colored people, the late slaves, into the body-politic as voters pointedly affronted the traditional prejudices prevailing among the Southern whites. What should we care about those prejudices? In war, nothing. After the close of the war, in the settlement of peace, not enough to deter us from doing what was right and necessary; and yet, still enough to take them into account when considering the manner in which right and necessity were to be served. Statesmen will care about popular prejudices as physicians will care about the diseased condition of their patients, which they want to ameliorate. Would it not have been wise for us, looking at those prejudices as a morbid condition of the Southern mind, to mitigate, to assuage, to disarm them by prudent measures and thus to weaken their evil influence? We desired the Southern whites to accept in good faith universal suffrage, to recognize the political rights of the colored man and to protect him in their exercise. Was not that our sincere desire? But if it was, would it not have been wise to remove as much as possible the obstacles that stood in the way of that consummation? But what did we do? When we raised the colored people to the rights of active citizenship and opened to them all the privileges of eligibility, we excluded from those privileges a large and influential class of whites; in other words, we lifted the late slave, uneducated and inexperienced as he was – I repeat, without his fault – not merely to the level of the late master class, but even above it. We asked certain white men to recognize the colored man in a political status not only as high but even higher than their own. . . . [W]as it wise to do it? If you desired the white man to accept and recognize the political equality of the black, was it wise to embitter and to exasperate his spirit with the stinging stigma of his own inferiority? . . . This was not assuaging, disarming prejudice; this was rather inciting, it was exasperating it. American statesmen will understand and appreciate human nature as it has developed itself under the influence of free institutions. We know that if we want any class of people to overcome their prejudices in respecting the political rights and privileges of any other class, the very first thing we have to do is to accord the same rights and privileges to them. No American was ever inclined to recognize in others public rights and privileges from which he himself was excluded; and for aught I know, in this very feeling, although it may take an objectionable form, we find one of the safeguards of popular liberty. . . .

. . . [T]he existence of disabilities, which put so large and influential a class of whites in point of political privileges below the colored people, could not fail to inflame those prejudices which stood in the way of a general and honest acceptance of the new order of things. They increased instead of diminishing the dangers and difficulties surrounding the emancipated class. . . .

Well, then, what policy does common-sense suggest to us now? If we sincerely desire to give to the Southern States good and honest government, material prosperity and measurable contentment, as far at least as we can contribute to that end; if we really desire to weaken and disarm those prejudices and resentments which still disturb the harmony of society, will it not be wise, will it not be necessary, will it not be our duty to show that we are in no sense the allies and abettors of those who use their political power to plunder their fellow-citizens, and that we do not mean to keep one class of people in unnecessary degradation by withholding from them rights and privileges which all others enjoy? Seeing the mischief which the system of disabilities is accomplishing, is it not time that there should be at least an end of it? Or is there any good it can possibly do to make up for the harm it has already wrought and is still working? . . . .

We hear the Ku-Klux outrages spoken of as a reason why political disabilities should not be removed. Did not these very same Ku-Klux outrages happen while disabilities were in existence? Is it not clear, then, that the existence of political disabilities did not prevent them? No, sir, if political disabilities have any practical effect, it is, while not in any degree diminishing the power of the evil-disposed for mischief, to incite and sharpen their mischievous inclination by increasing their discontent with the condition they live in.

It must be clear to every impartial observer that, were ever so many of those who are now disqualified, put in office, they never could do with their official power as much mischief as the mere fact of the existence of the system of political disabilities with its inevitable consequences is doing to-day. The scandals of misgovernment in the South which we complain of, I admit, were not the first and original cause of the Ku-Klux outrages. But every candid observer will also have to admit that they did serve to keep the Ku-Klux spirit alive. . . .

We accuse the Southern whites of having missed their chance of gaining the confidence of the emancipated class when, by a fairly demonstrated purpose of recognizing and protecting them in their rights, they might have acquired upon them a salutary influence. That accusation is by no means unjust; but must we not admit, also, that by excluding them from their political rights and privileges we put the damper of most serious discouragement upon the good intentions which might have grown up among them? . . . You find nothing, absolutely nothing, in [the] practical effects [of the disabilities] but the aggravation of evils already existing and the prevention of a salutary development. . . .

But I am told that the system of disabilities must be maintained for a certain moral effect. The Senator from Indiana [Mr. Morton3] took great pains to inform us that it is absolutely necessary to exclude somebody from office in order to demonstrate our disapprobation of the crime of rebellion. Methinks the American people have signified their disapprobation of the crime of rebellion in a far more pointed manner. They sent against the rebellion a million armed men. We fought and conquered the armies of the rebels; we carried desolation into their land; we swept out of existence that system of slavery which was the soul of their offense and was to be the corner-stone of their new empire. If that was not signifying our disapprobation of the crime of rebellion, then I humbly submit, your system of political disabilities, only excluding some persons from office, will scarcely do it.

I remember, also, to have heard the argument that under all circumstances the law must be vindicated. What law in this case? If any law is meant, it must be the law imposing the penalty of death upon the crime of treason. Well, if at the close of the war we had assumed the stern and bloody virtue of the ancient Roman, and had proclaimed that he who raises his hand against this Republic must surely die, then we might have claimed for ourselves at least the merit of logical consistency. We might have thought that by erecting a row of gallows stretching from the Potomac to the Rio Grande, and by making a terrible example of all those who had proved faithless to their allegiance, we would strike terror into the hearts of this and coming generations, to make them tremble at the mere thought of treasonable undertakings. That we might have done. Why did we not? Because the American people instinctively recoiled from the idea; because every wise man remembered that where insurrections are punished and avenged with the bloodiest hands, there insurrections do most frequently occur . . . .

. . . We instinctively adopted a generous policy, adding fresh luster to the glory of the American name by doing so. . . .

But having once adopted the policy of generosity, the only question for us is how to make that policy most fruitful. The answer is: We shall make the policy of generosity most fruitful by making it most complete. . . .

. . . Whatever may be said of the greatness and the heinous character of the crime of rebellion, a single glance at the history of the world and at the practice of other nations will convince you, that in all civilized countries the measure of punishment to be visited on those guilty of that crime is almost uniformly treated as a question of great policy and almost never as a question of strict justice. And why is this? . . . . Because a broad line of distinction is drawn between a violation of law in which political opinion is the controlling element . . . and those infamous crimes of which moral depravity is the principal ingredient; and because even the most disastrous political conflicts may be composed for the common good by a conciliatory process, while the infamous crime always calls for a strictly penal correction. You may call this just or not, but such is the public opinion of the civilized world, and you find it in every civilized country. . . .

I do not, indeed, indulge in the delusion that this act alone will remedy all the evils which we now deplore. No, it will not; but it will be a powerful appeal to the very best instincts and impulses of human nature; . . . it will give new courage, confidence and inspiration to the well-disposed; it will weaken the power of the mischievous, by stripping of their pretexts and exposing in their nakedness the wicked designs they still may cherish; it will light anew the beneficent glow of fraternal feeling and of National spirit; for, sir, your good sense as well as your heart must tell you that, when this is truly a people of citizens equal in their political rights, it will then be easier to make it also a people of brothers.

- 1. Schurz refers to Section 3, which excluded those who had broken an oath of office and joined a rebellion against the United States from holding office again.

- 2. Schurz seems to refer to carpetbaggers – Northern men who went South to govern and engage in commerce. They had a reputation for corruption, for looking to make a quick dollar, but this reputation is mostly a result of Southern efforts to discredit Northern rule.

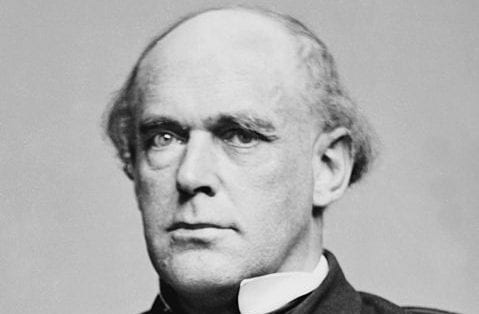

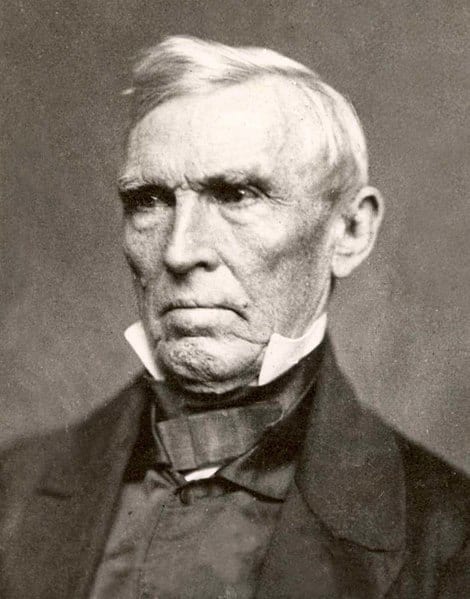

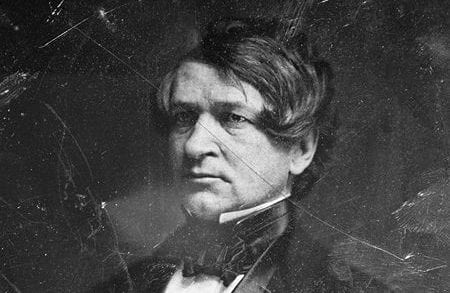

- 3. Oliver H. P. T. Morton, R (1823–1877)

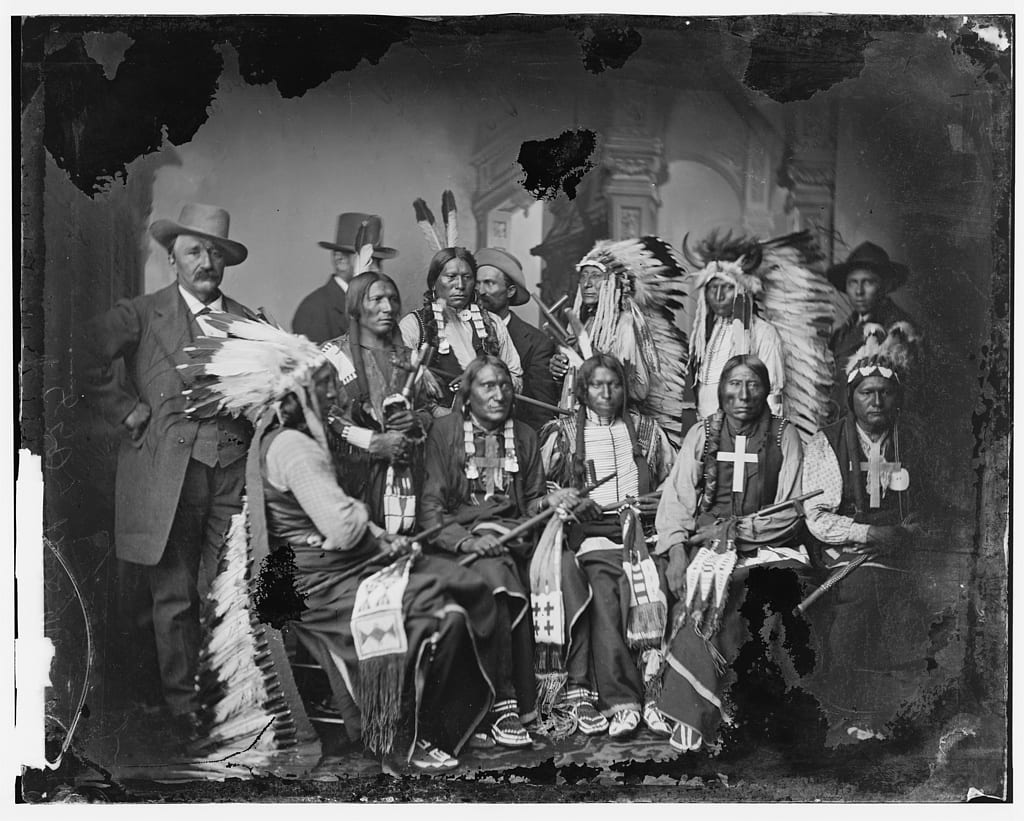

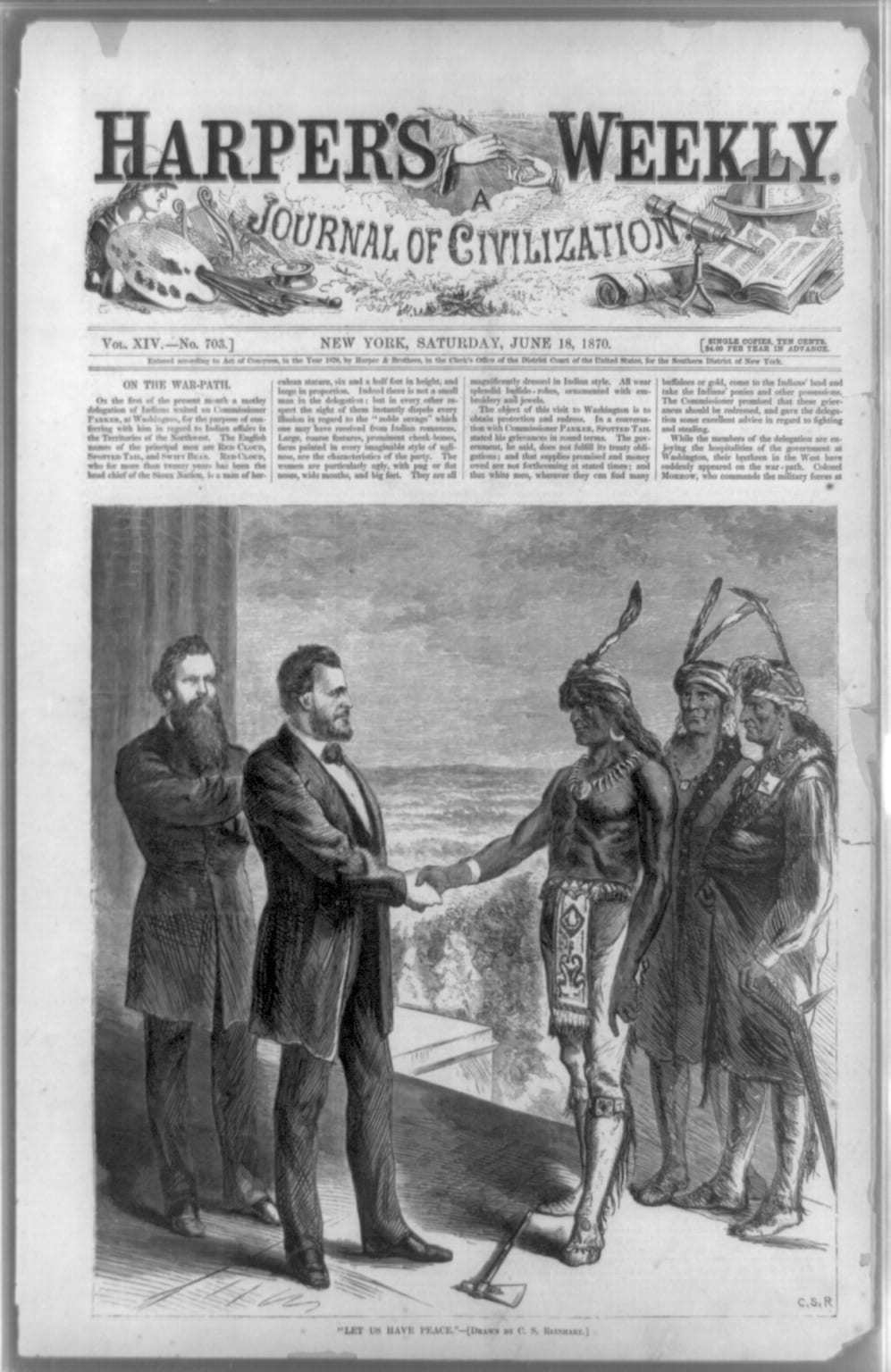

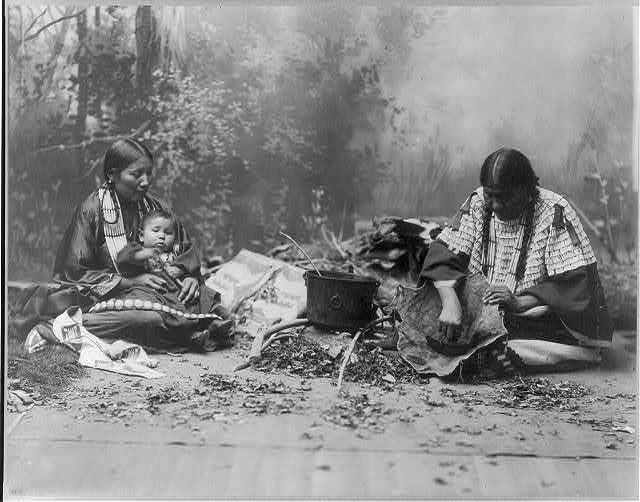

Speech to Red Cloud and Red Dog

May 28, 1872

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.