No related resources

Introduction

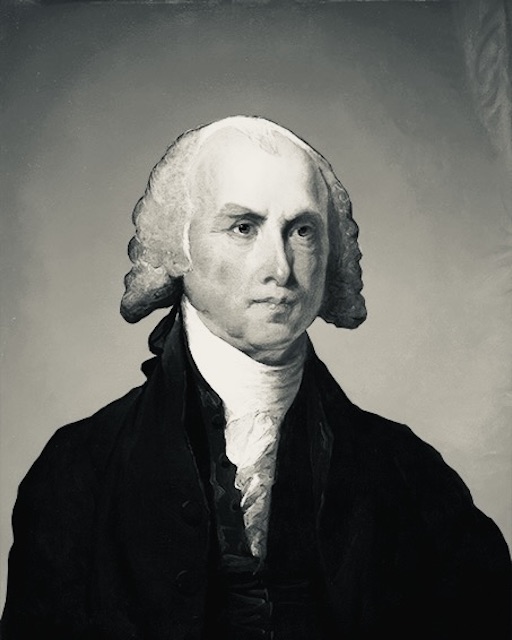

After a number of state legislatures responded (Massachusetts Legislature, Response) to the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 by condemning the claims and doctrines advanced in those resolutions, the Virginia General Assembly prepared a report, drafted principally by James Madison (1751–1836), defending the Virginia Resolutions against criticisms leveled by other states.

The Virginia General Assembly did not retreat from any of the claims advanced in the Virginia Resolutions, including the claim “that the states are parties to the Constitution or compact,” though the Report of 1800 made clear that in speaking of “states” in this context, the intent was to refer to “the people composing those political societies, in their highest sovereign capacity.” When the references in the Virginia Resolutions to the “states” are understood in that sense, the General Assembly maintained that it was clear that the Constitution had been submitted to and ratified by the states, which “are consequently parties to the compact from which the powers of the federal government result.”

The Virginia General Assembly also reiterated its claim that states, as “parties to the constitutional compact,” retained the ability to determine when federal officials had exceeded their legitimate powers under the Constitution, while stressing various statements in the Virginia Resolutions qualifying this power. In a multipronged response, the Report of 1800 also confronted the most prominent criticism leveled by other state legislatures against the Virginia Resolutions: that the federal judiciary was “the sole expositor of the Constitution,” thereby removing any need for states to pass judgment on the constitutionality of federal acts.

Source: “The Report of 1800, [7 January] 1800,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-17-02-0202.

Whatever room might be found in the proceedings of some of the states, who have disapproved of the resolutions of the General Assembly of this commonwealth, passed on the 21st day of December, 1798, for painful remark on the spirit and manner of those proceedings, it appears to the committee, most consistent with the duty, as well as dignity of the General Assembly, to hasten an oblivion of every circumstance which might be construed into a diminution of mutual respect, confidence, and affection among the members of the Union.

The committee have deemed it a more useful task, to revise with a critical eye, the resolutions which have met with this disapprobation; to examine fully the several objections and arguments which have appeared against them; and to inquire whether there be any errors of fact, of principle, or of reasoning, which the candor of the General Assembly ought to acknowledge and correct....

The third resolution is in the words following:

That this Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact, to which the states are parties, as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting that compact; as no farther valid than they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact; and that in case of a deliberate, palpable and dangerous exercise of other powers not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties thereto have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose, for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them.

On this resolution, the committee have bestowed all the attention which its importance merits: They have scanned it not merely with a strict, but with a severe eye; and they feel confidence in pronouncing that in its just and fair construction, it is unexceptionably true in its several positions, as well as constitutional and conclusive in its inferences.

The resolution declares, first, that “it views the powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact to which the states are parties,” in other words, that the federal powers are derived from the Constitution, and that the Constitution is a compact to which the states are parties.

Clear as the position must seem that the federal powers are derived from the Constitution, and from that alone, the committee are not unapprised of a late doctrine which opens another source of federal powers, not less extensive and important, than it is new and unexpected. The examination of this doctrine will be most conveniently connected with a review of a succeeding resolution. The committee satisfy themselves here with briefly remarking, that in all the contemporary discussions and comments which the Constitution underwent, it was constantly justified and recommended on the ground, that the powers not given to the government were withheld from it; and that if any doubt could have existed on this subject, under the original text of the Constitution, it is removed as far as words could remove it, by the 12th amendment,1 now a part of the Constitution, which expressly declares “that the powers not delegated to the United States, by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.”

The other position involved in this branch of the resolution, namely, “that the states are parties to the Constitution or compact,” is in the judgment of the committee, equally free from objection. It is indeed true that the term “states” is sometimes used in a vague sense, and sometimes in different senses, according to the subject to which it is applied. Thus it sometimes means the separate sections of territory occupied by the political societies within each; sometimes the particular governments established by those societies; sometimes those societies as organized into those particular governments; and lastly, it means the people composing those political societies, in their highest sovereign capacity. Although it might be wished that the perfection of language admitted less diversity in the signification of the same words, yet little inconvenience is produced by it, where the true sense can be collected with certainty from the different applications. In the present instance whatever different constructions of the term “states” in the resolution may have been entertained, all will at least concur in that last mentioned; because in that sense, the Constitution was submitted to the “states.” In that sense the “states” ratified it; and in that sense of the term “states,” they are consequently parties to the compact from which the powers of the federal government result.

The next position is, that the General Assembly views the powers of the federal government “as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting that compact,” and “as no farther valid than they are authorized by the grants therein enumerated.” It does not seem possible that any just objection can lie against either of these clauses. The first amounts merely to a declaration that the compact ought to have the interpretation plainly intended by the parties to it; the other, to a declaration that it ought to have the execution and effect intended by them. If the powers granted be valid, it is solely because they are granted; and if the granted powers are valid, because granted, all other powers not granted must not be valid.

The resolution having taken this view of the federal compact, proceeds to infer “that in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties thereto have the right, and are in duty bound to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them.”

It appears to your committee to be a plain principle, founded in common sense, illustrated by common practice, and essential to the nature of compacts; that where resort can be had to no tribunal superior to the authority of the parties, the parties themselves must be the rightful judges in the last resort, whether the bargain made has been pursued or violated. The Constitution of the United States was formed by the sanction of the states, given by each in its sovereign capacity. It adds to the stability and dignity, as well as to the authority of the Constitution, that it rests on this legitimate and solid foundation. The states then being the parties to the constitutional compact, and in their sovereign capacity, it follows of necessity that there can be no tribunal above their authority, to decide in the last resort, whether the compact made by them be violated; and consequently that as the parties to it, they must themselves decide in the last resort such questions as may be of sufficient magnitude to require their interposition.

It does not follow, however, that because the states as sovereign parties to their constitutional compact must ultimately decide whether it has been violated, that such a decision ought to be interposed either in a hasty manner, or on doubtful and inferior occasions. Even in the case of ordinary conventions between different nations, where, by the strict rule of interpretation, a breach of a part may be deemed a breach of the whole; every part being deemed a condition of every other part, and of the whole, it is always laid down that the breach must be both willful and material to justify an application of the rule. But in the case of an intimate and constitutional union, like that of the United States, it is evident that the interposition of the parties, in their sovereign capacity, can be called for by occasions only deeply and essentially affecting the vital principles of their political system.

The resolution has accordingly guarded against any misapprehension of its object, by expressly requiring for such an interposition “the case of a deliberate, palpable and dangerous breach of the Constitution, by the exercise of powers not granted by it.” It must be a case, not of a light and transient nature, but of a nature dangerous to the great purposes for which the Constitution was established. It must be a case moreover not obscure or doubtful in its construction, but plain and palpable. Lastly, it must be a case not resulting from a partial consideration, or hasty determination; but a case stamped with a final consideration and deliberate adherence. It is not necessary because the resolution does not require that the question should be discussed, how far the exercise of any particular power, ungranted by the Constitution, would justify the interposition of the parties to it. As cases might easily be stated, which none would contend, ought to fall within that description: Cases, on the other hand, might, with equal ease, be stated, so flagrant and so fatal as to unite every opinion in placing them within the description.

But the resolution has done more than guard against misconstruction, by expressly referring to cases of a deliberate, palpable and dangerous nature. It specifies the object of the interposition which it contemplates to be solely that of arresting the progress of the evil of usurpation, and of maintaining the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to the states, as parties to the Constitution.

From this view of the resolution, it would seem inconceivable that it can incur any just disapprobation from those, who laying aside all momentary impressions, and recollecting the genuine source and object of the federal Constitution, shall candidly and accurately interpret the meaning of the General Assembly. If the deliberate exercise of dangerous powers, palpably withheld by the Constitution, could not justify the parties to it in interposing even so far as to arrest the progress of the evil, and thereby to preserve the Constitution itself as well as to provide for the safety of the parties to it; there would be an end to all relief from usurped power, and a direct subversion of the rights specified or recognized under all the state constitutions, as well as a plain denial of the fundamental principle on which our independence itself was declared.

But it is objected that the judicial authority is to be regarded as the sole expositor of the Constitution, in the last resort; and it may be asked for what reason the declaration by the General Assembly supposing it to be theoretically true could be required at the present day and in so solemn a manner.

On this objection it might be observed first, that there may be instances of usurped power, which the forms of the Constitution would never draw within the control of the judicial department: secondly, that if the decision of the judiciary be raised above the authority of the sovereign parties to the Constitution, the decisions of the other departments, not carried by the forms of the Constitution before the judiciary, must be equally authoritative and final with the decisions of that department. But the proper answer to the objection is that the resolution of the General Assembly relates to those great and extraordinary cases in which all the forms of the Constitution may prove ineffectual against infractions dangerous to the essential rights of the parties to it. The resolution supposes that dangerous powers not delegated may not only be usurped and executed by the other departments, but that the Judicial Department also may exercise or sanction dangerous powers beyond the grant of the Constitution; and consequently that the ultimate right of the parties to the Constitution to judge whether the compact has been dangerously violated must extend to violations by one delegated authority, as well as by another; by the judiciary, as well as by the executive, or the legislature.

However true therefore it may be that the Judicial Department is in all questions submitted to it by the forms of the Constitution to decide in the last resort, this resort must necessarily be deemed the last in relation to the authorities of the other departments of the government; not in relation to the rights of the parties to the constitutional compact, from which the judicial as well as the other departments hold their delegated trusts. On any other hypothesis, the delegation of judicial power would annul the authority delegating it; and the concurrence of this department with the others in usurped powers might subvert forever and beyond the possible reach of any rightful remedy the very Constitution which all were instituted to preserve.

The truth declared in the resolution being established, the expediency of making the declaration at the present day, may safely be left to the temperate consideration and candid judgment of the American public. It will be remembered that a frequent recurrence to fundamental principles is solemnly enjoined by most of the state constitutions, and particularly by our own,2 as a necessary safeguard against the danger of degeneracy to which republics are liable, as well as other governments, though in a less degree than others. And a fair comparison of the political doctrines not unfrequent at the present day, with those which characterized the epoch of our revolution, and which form the basis of our republican constitutions, will best determine whether the declaratory recurrence here made to those principles ought to be viewed as unseasonable and improper, or as a vigilant discharge of an important duty. The authority of constitutions over governments, and of the sovereignty of the people over constitutions, are truths which are at all times necessary to be kept in mind; and at no time perhaps more necessary than at the present....

- 1. The Tenth Amendment to the Constitution originated as the twelfth of twelve amendments that Congress in 1789 approved for submission to state legislatures for ratification. The first two amendments were not initially approved (the original First Amendment dealing with apportionment of the House was never approved, and the original Second Amendment dealing with congressional pay raises was not approved until 1992). The third through twelfth of the proposed amendments eventually became the First through Tenth Amendments. Because it was unclear for some time which of the original twelve proposed amendments would eventually be ratified, officials referred to each of the amendments by the number they were assigned by the First Congress. Therefore, what is understood today to be the Tenth Amendment was referred to as the Twelfth Amendment in some writings during this period.

- 2. The Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776), Section 15 states “that no free government, or the blessings of liberty, can be preserved to any people but by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality, and virtue and by frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.”

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)