Introduction

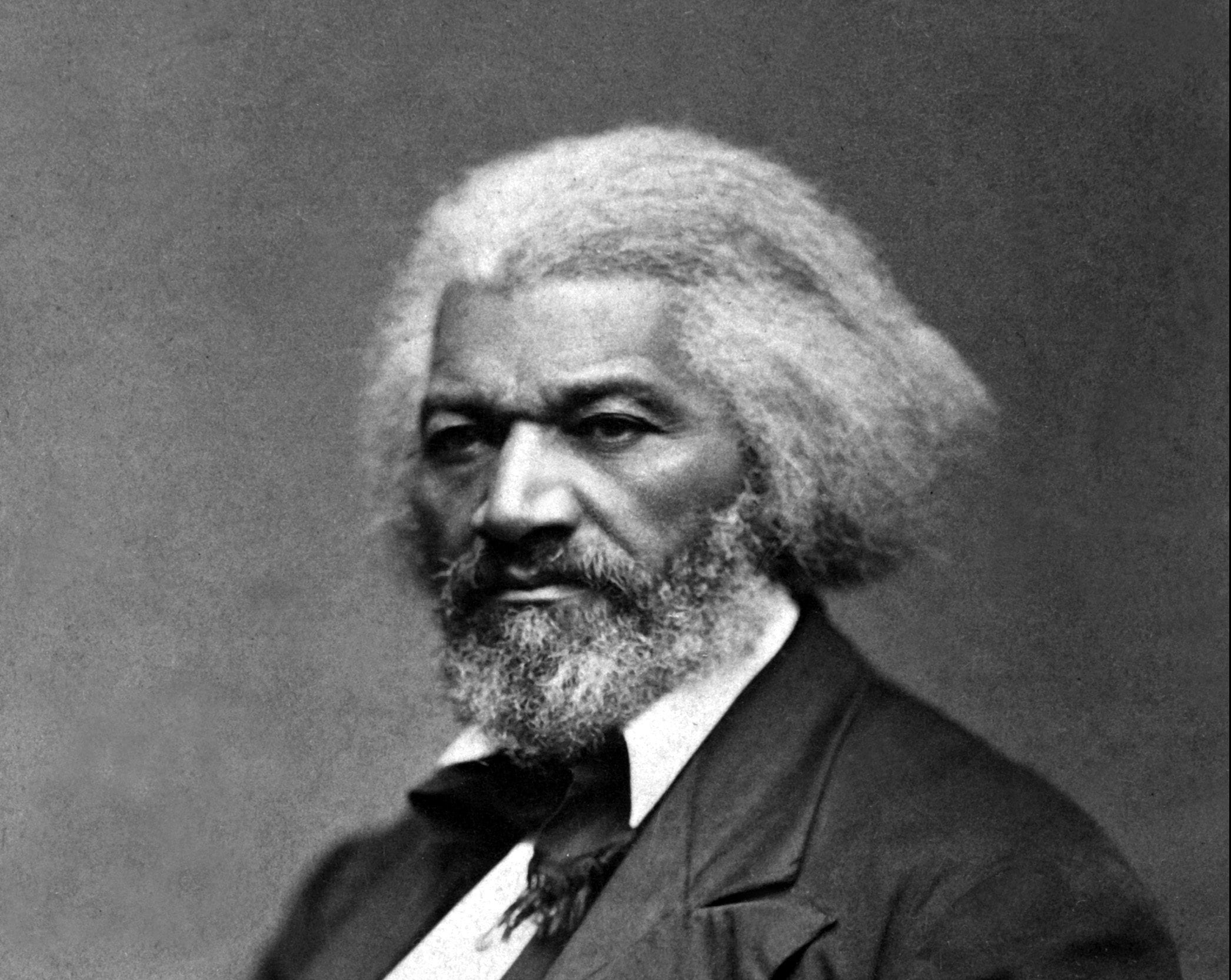

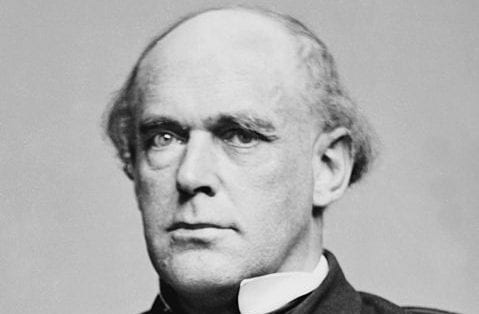

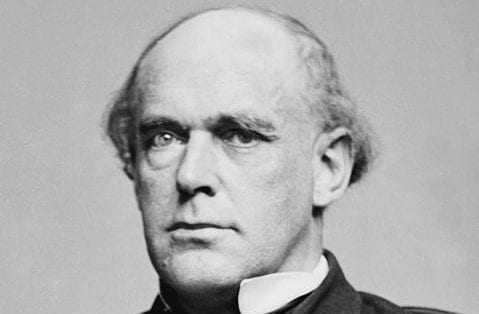

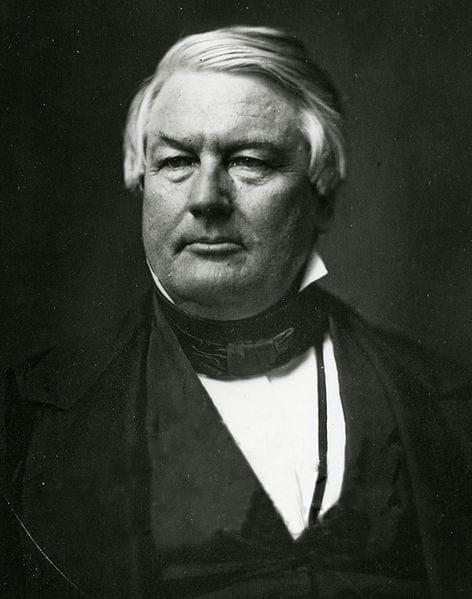

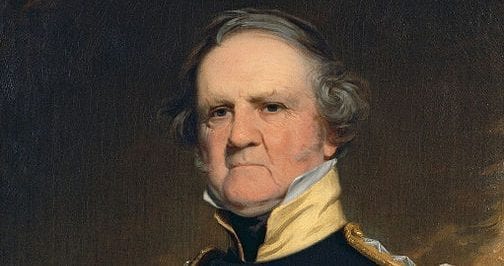

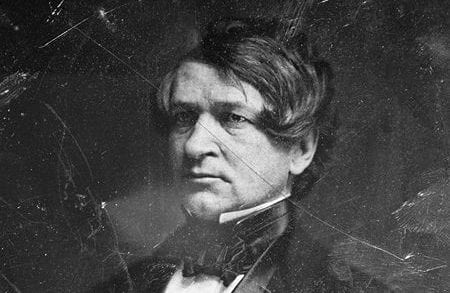

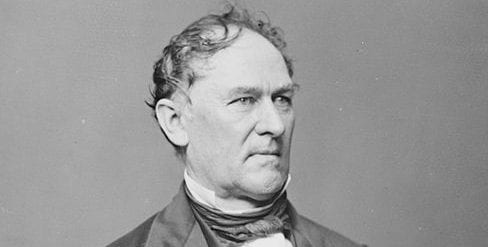

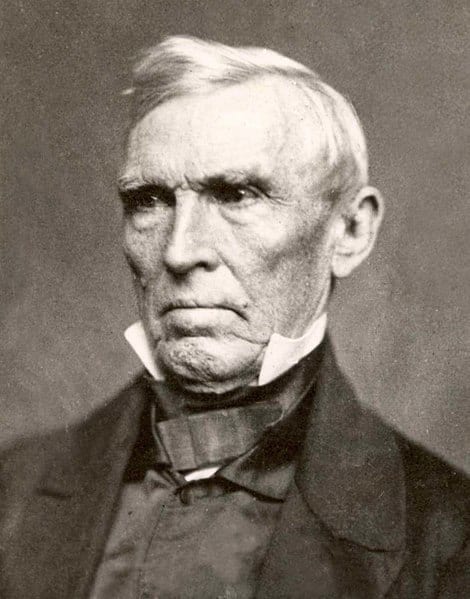

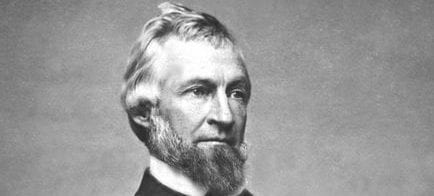

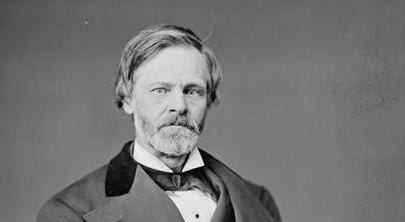

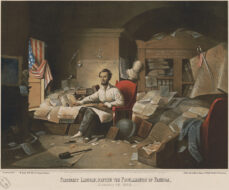

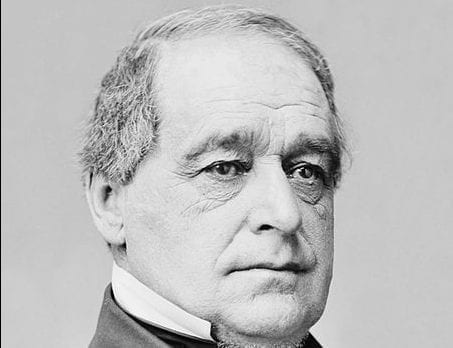

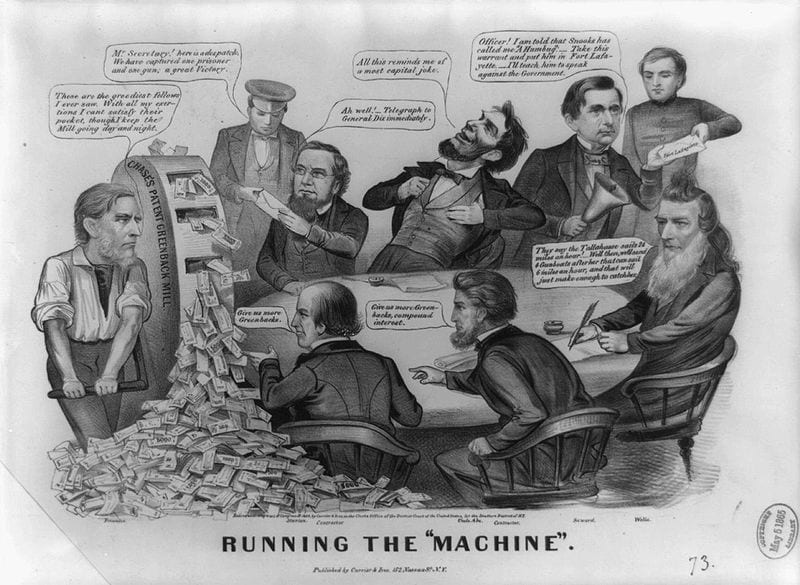

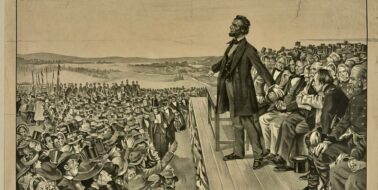

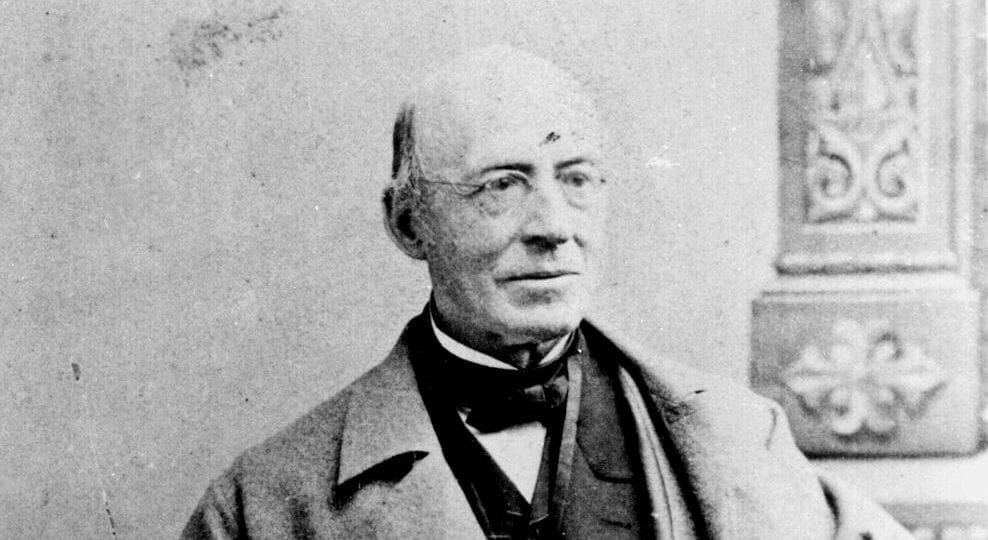

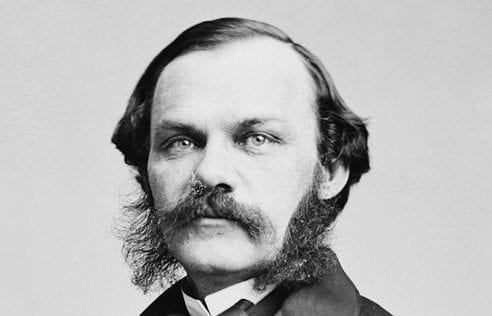

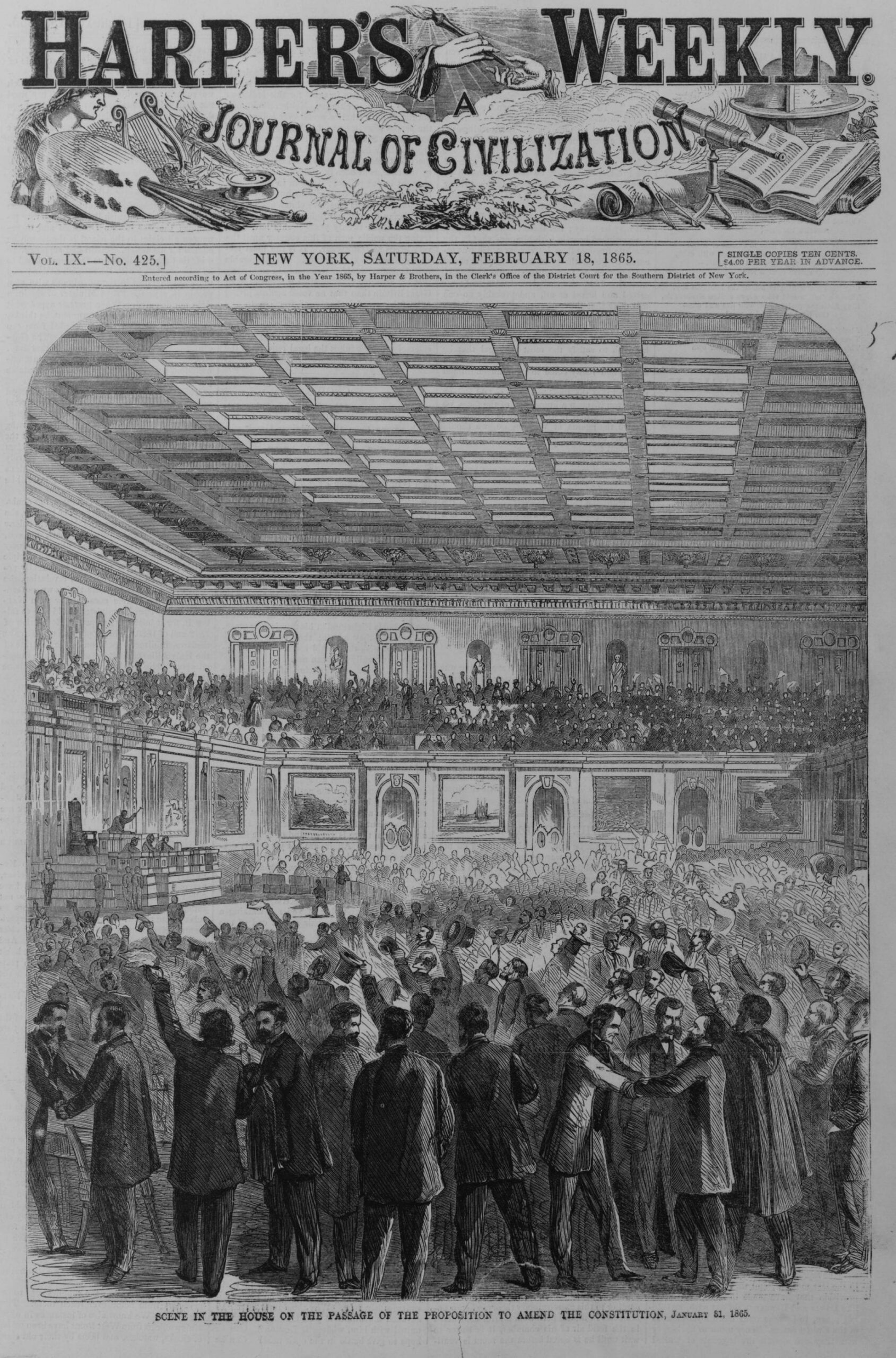

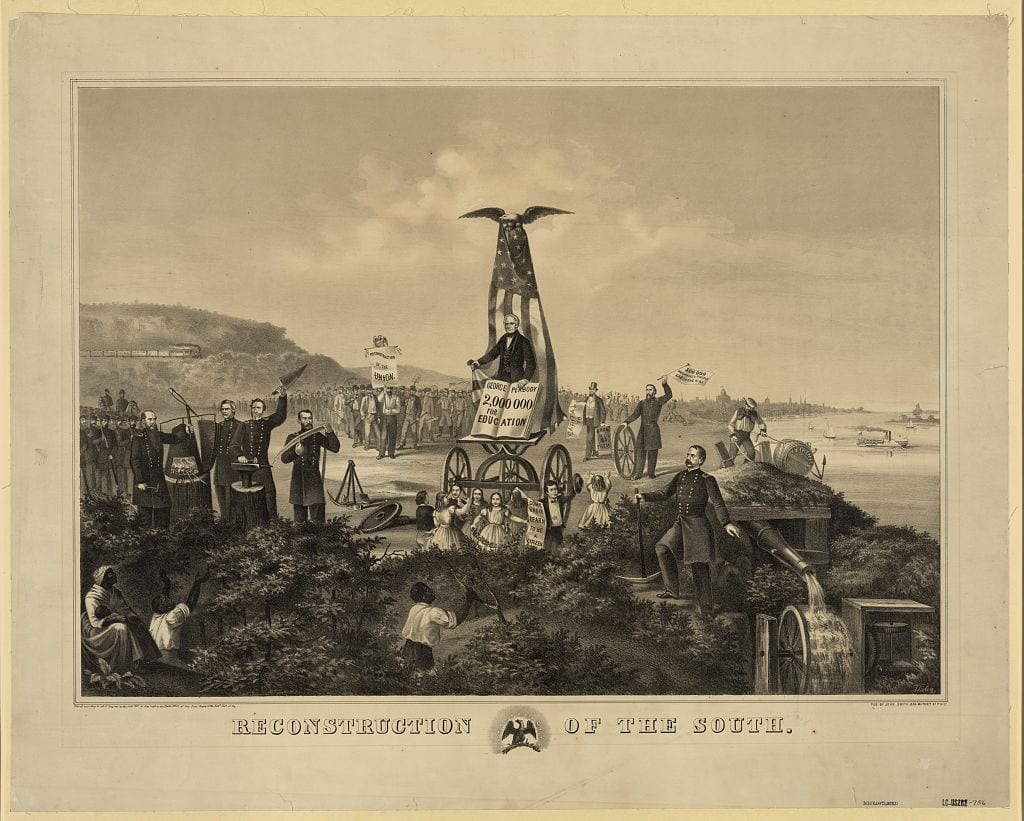

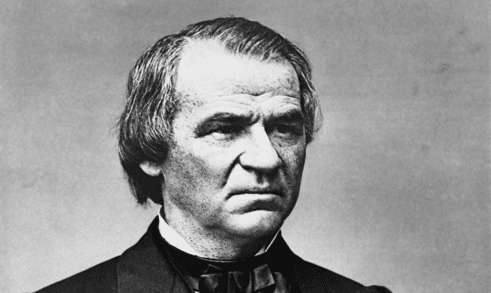

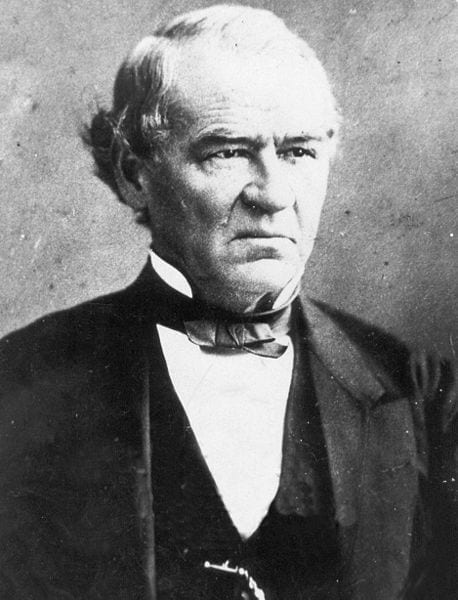

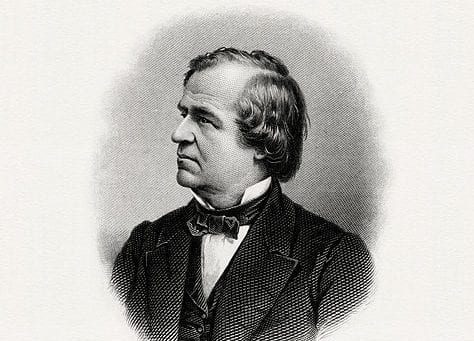

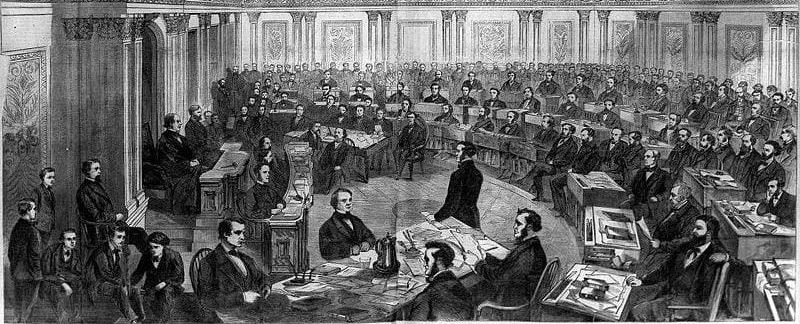

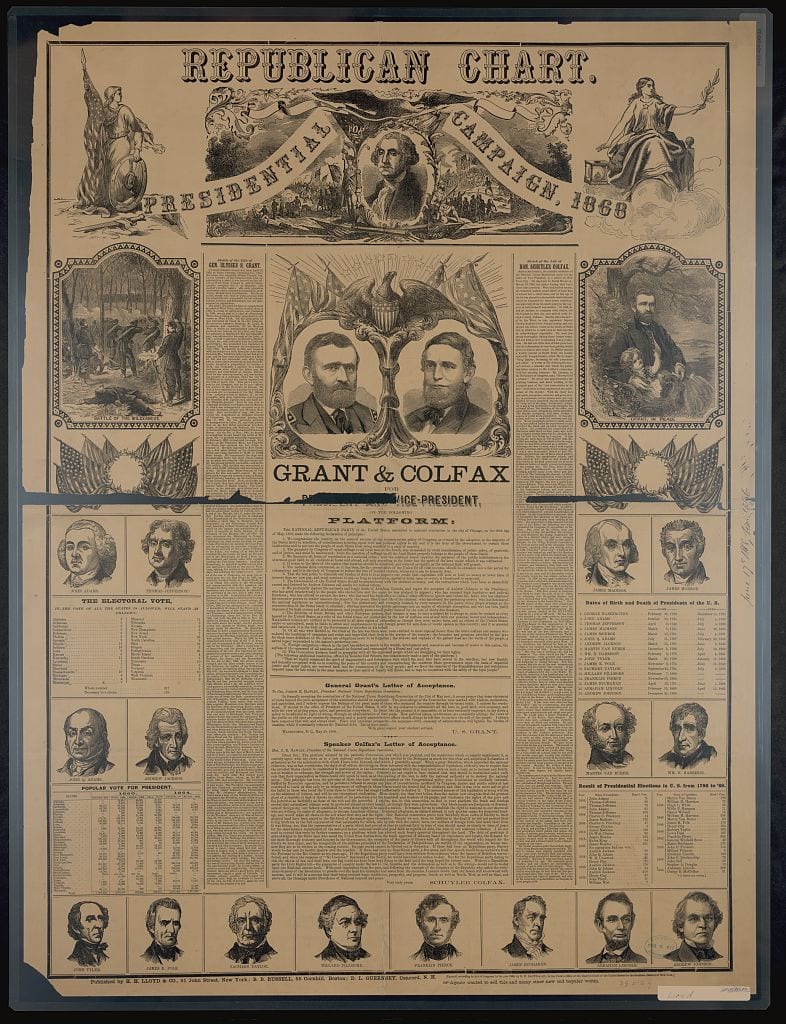

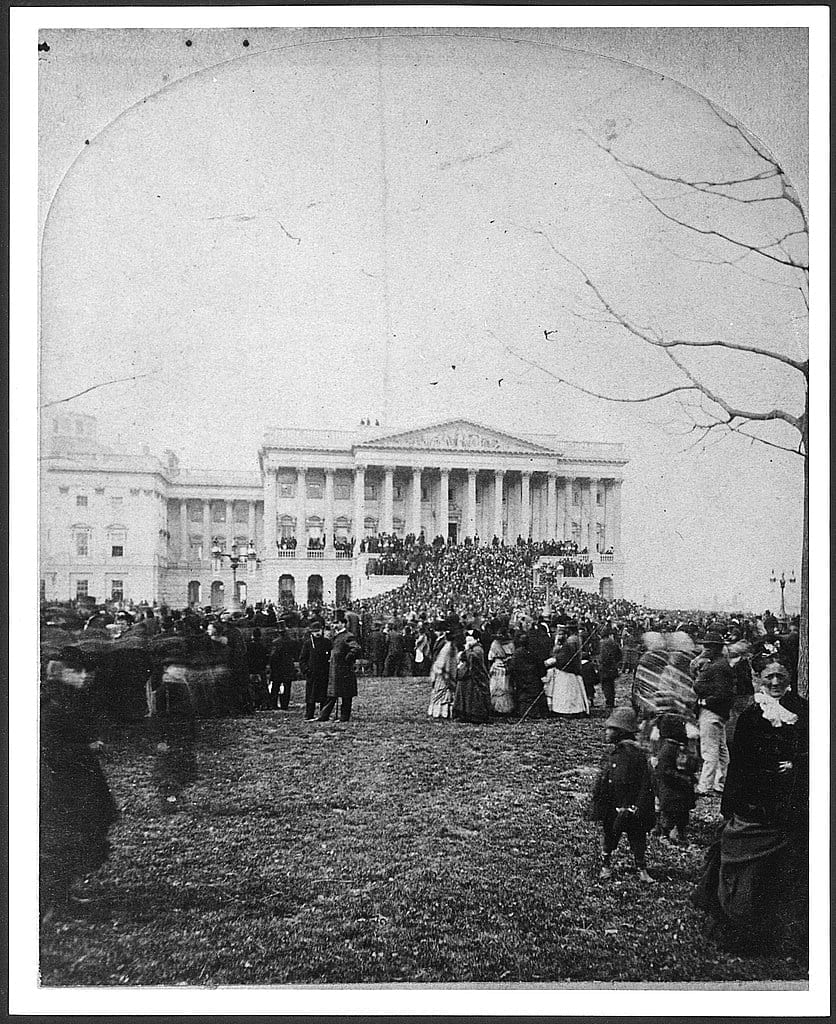

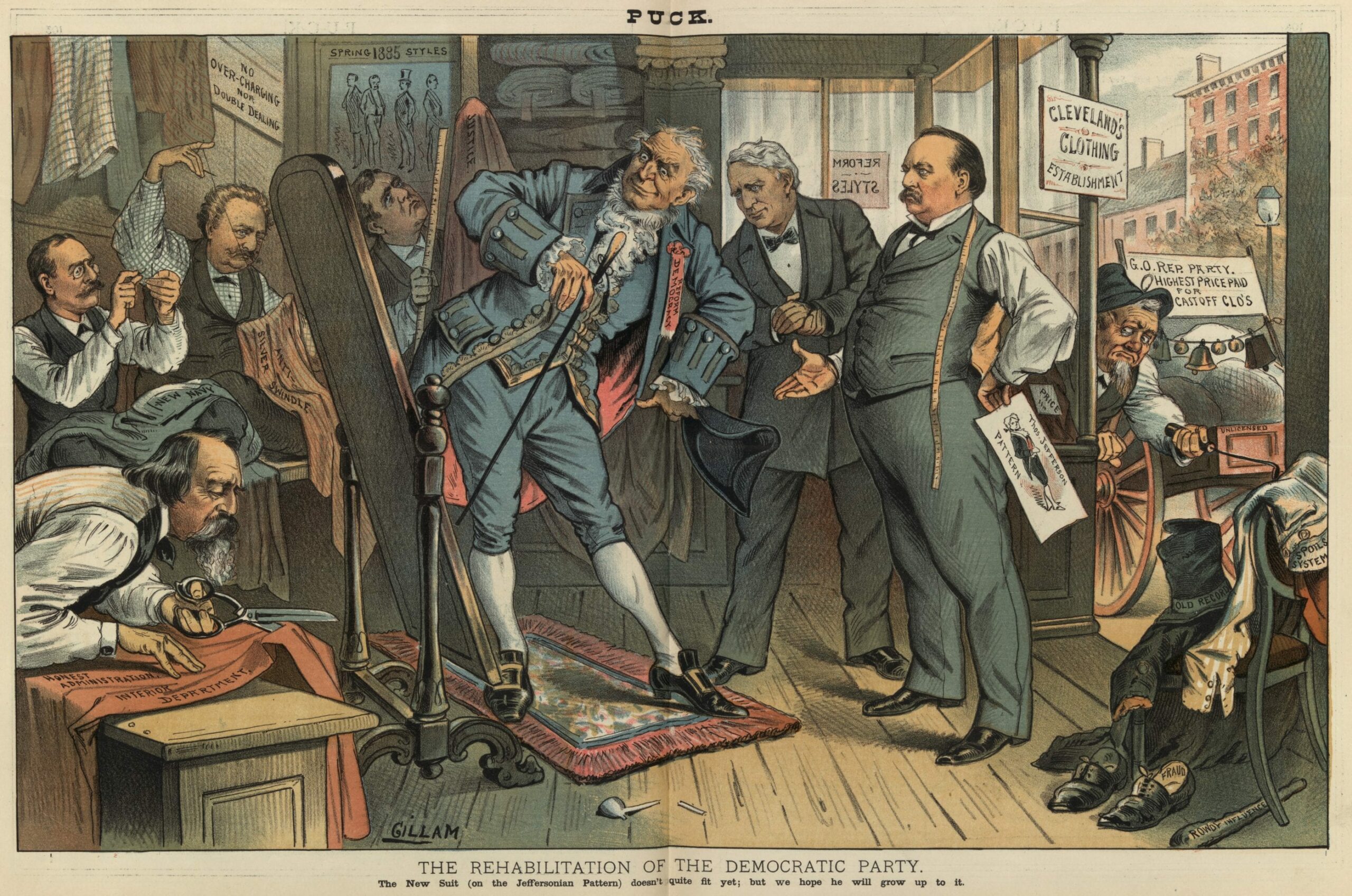

Republicans won veto-proof majorities in both Houses of Congress in the 1866 elections. Seeing this victory as support, within limits, of their approach to reconstruction, a leading radical Republican, Representative Thaddeus Stevens (R-PA; 1792-1868), took the floor of the House of Representatives to outline his vision of Reconstruction and to support the Reconstruction Acts that Congress was considering. Like Senator Charles Sumner, Stevens was pushing for national efforts beyond the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the 14th Amendment.

Source: Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 2nd sess., Jan. 3, 1867, pp. 251-253. Available at A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875, American Memory, an online collection of the Library of Congress, https://goo.gl/uiPKjL.

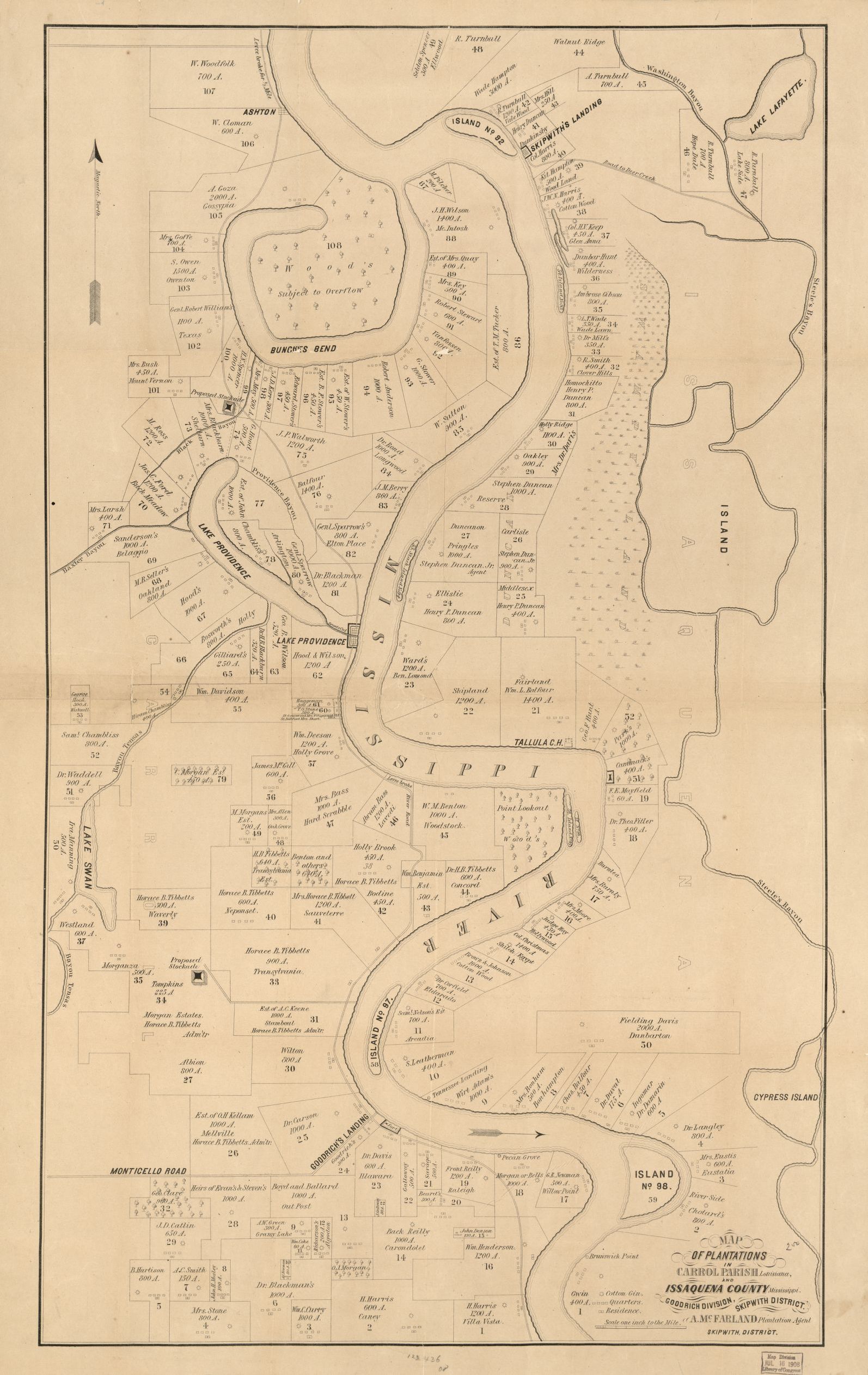

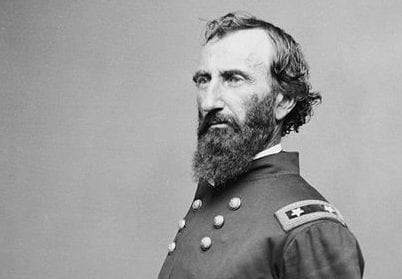

. . . This is a bill designed to enable loyal men, so far as I could discriminate them in these States, to form governments which shall be in loyal hands, that they may protect themselves from . . . outrages . . . In states that have never been restored since the rebellion from a state of conquest, and which are this day held in captivity under the laws of war, the military authorities, under this decision and its extension into disloyal states, dare not order the commanders of departments to enforce the laws of the country. . . .

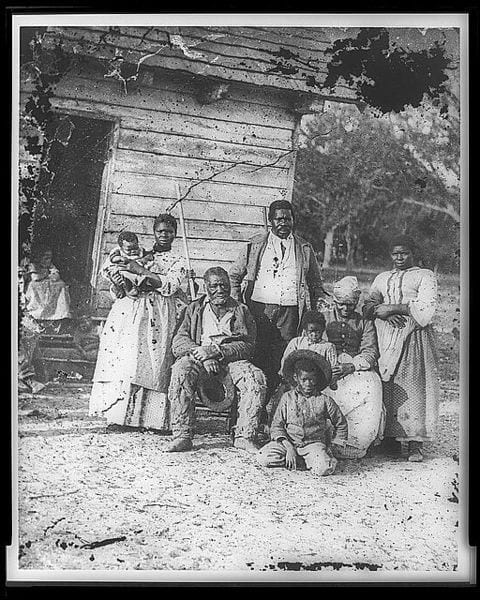

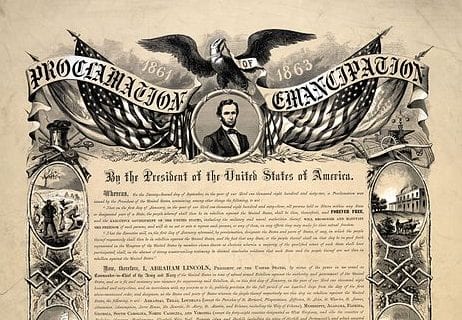

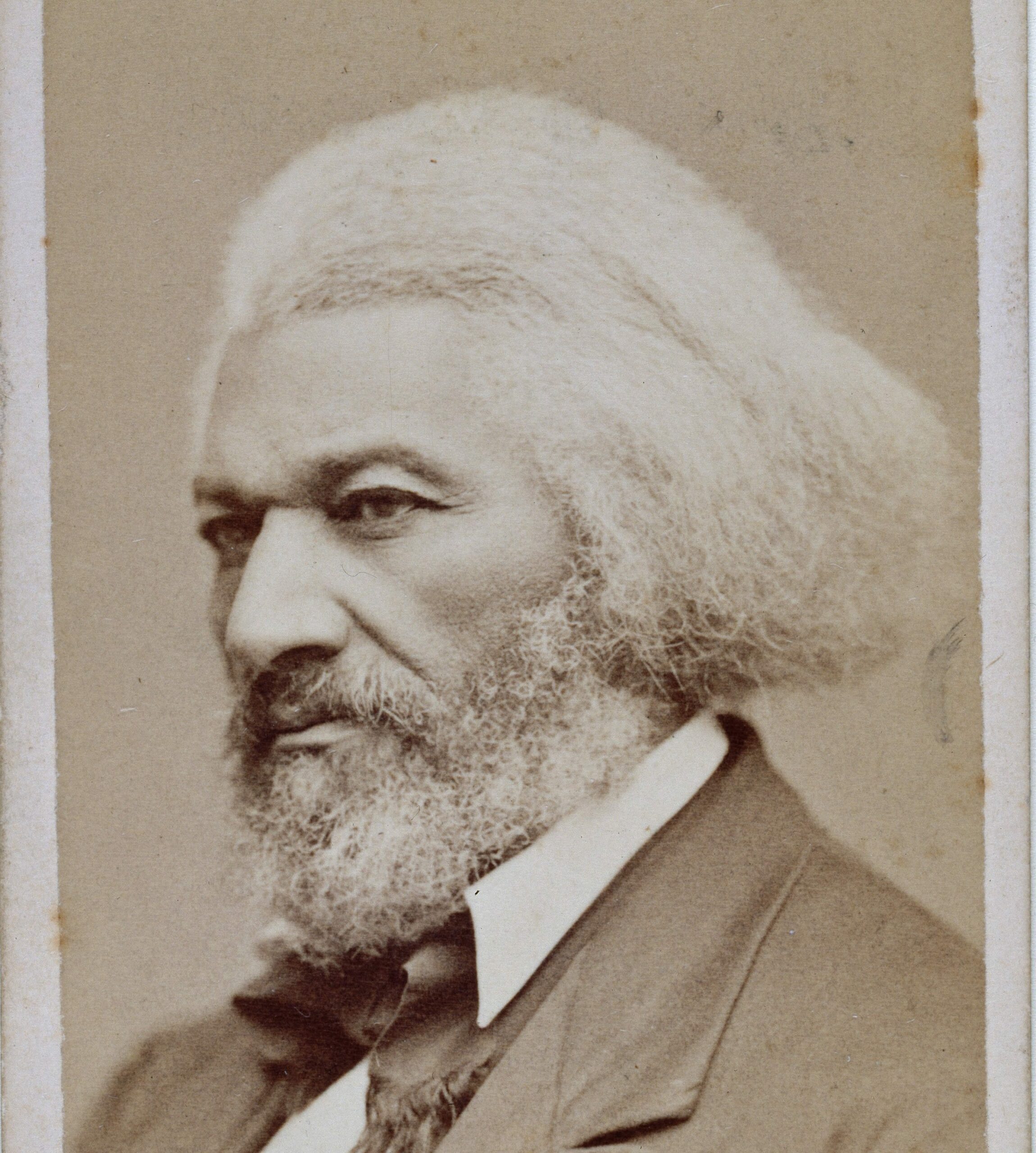

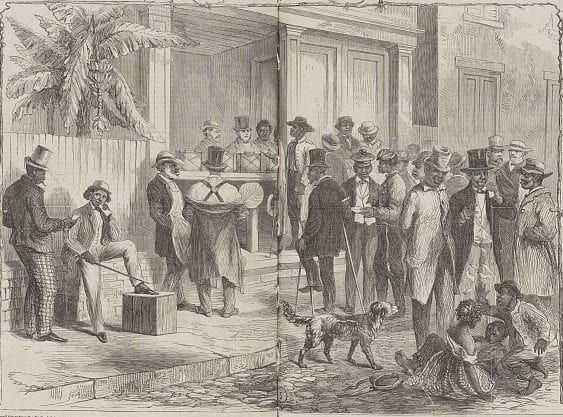

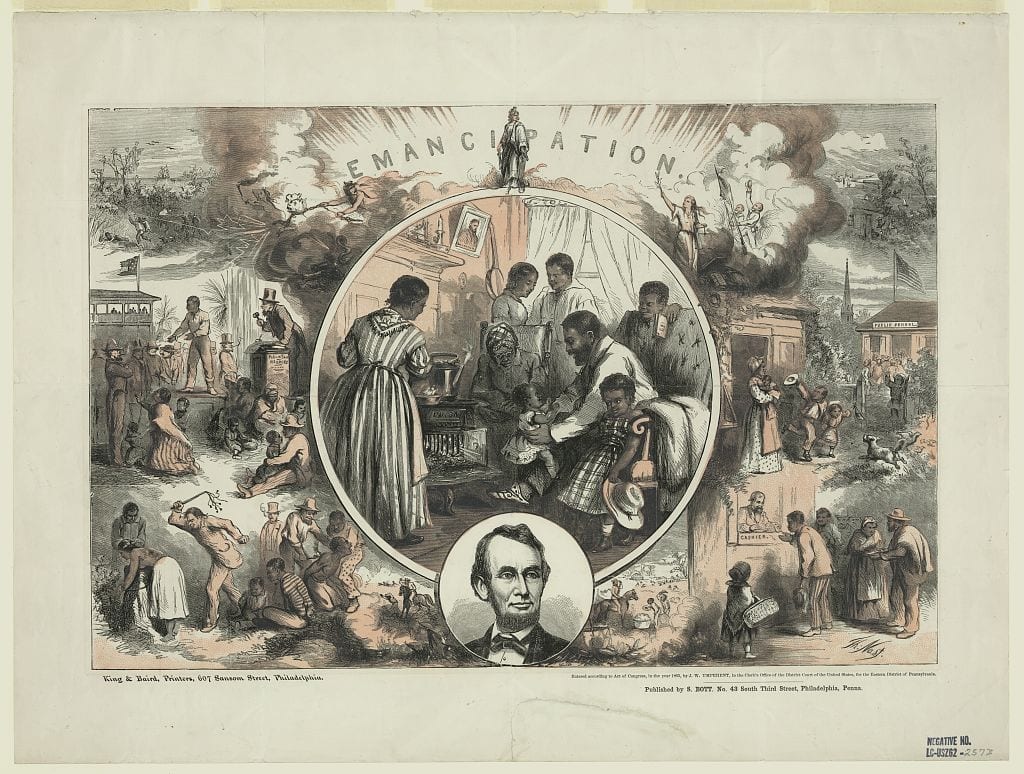

Since the surrender of the armies of the confederate States of America a little has been done toward establishing this Government upon the true principles of liberty and justice. . . . But in what have we enlarged their liberty of thought? In what have we taught them the science and granted them the privilege of self-government? . . . Call you this a free Republic when four millions are subjects but not citizens? . . . I pronounce it no nearer to a true Republic now when twenty-five million of a privileged class exclude five million[1] from all participation in the rights of government. . . .

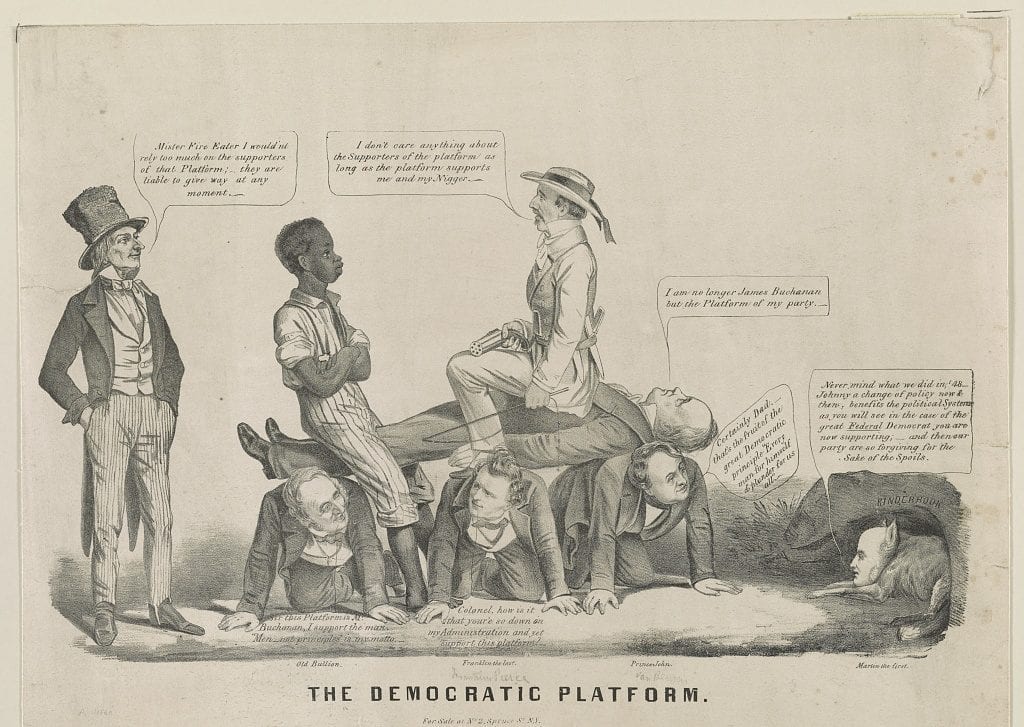

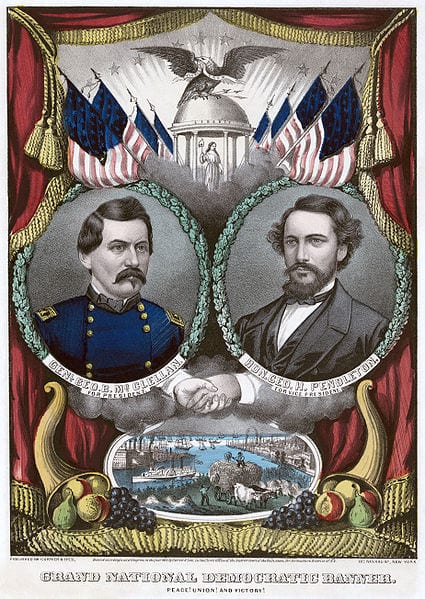

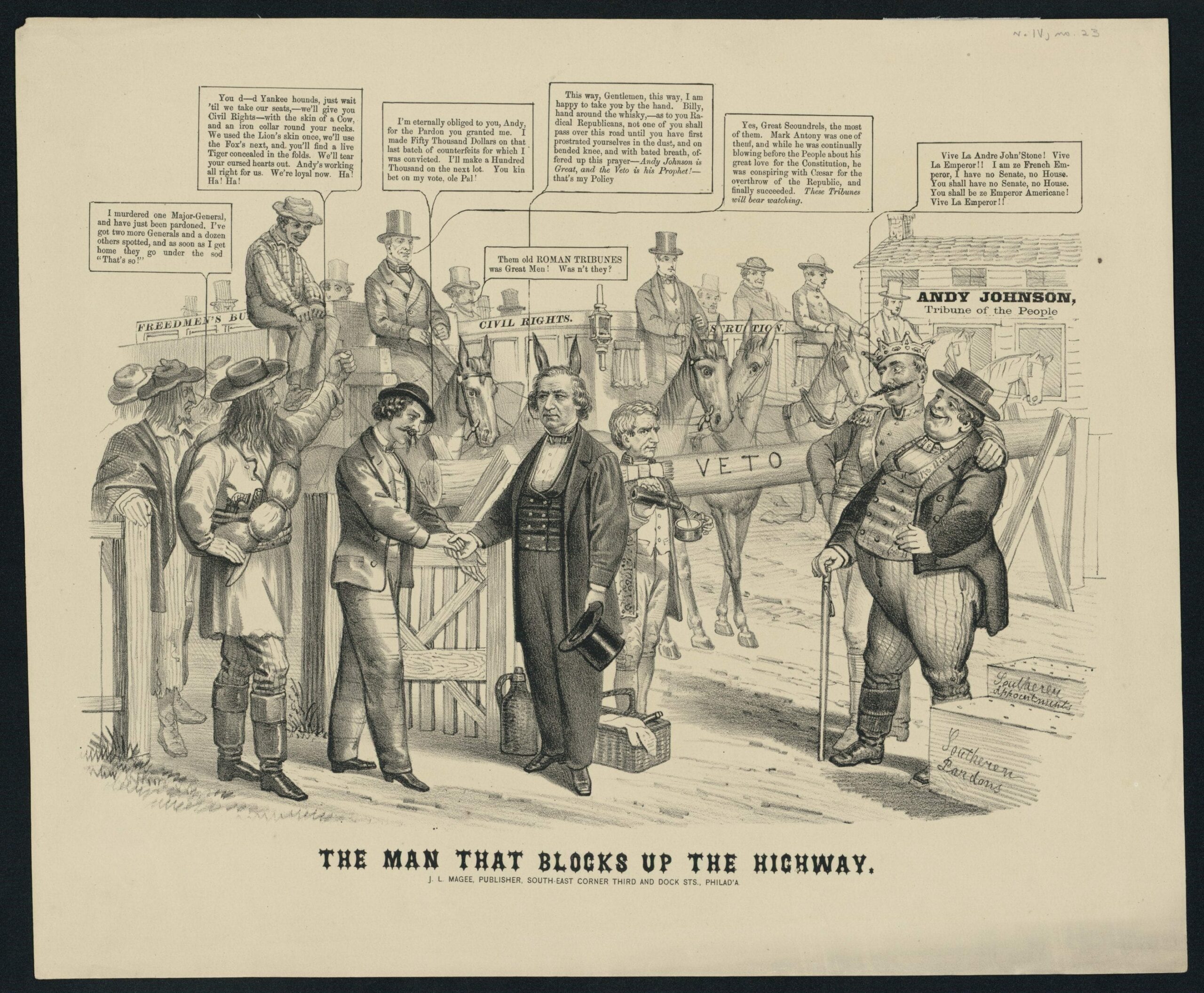

What are the great questions which now divide the nation? In the midst of the political Babel which has been produced by the intermingling of secessionists, rebels, pardoned traitors, hissing Copperheads,[2] and apostate Republicans, such a confusion of tongues is heard that it is difficult to understand either the questions that are asked or the answers that are given. Ask, what is the “President’s policy?” and it is difficult to define it. Ask, what is the “policy of Congress?” and the answer is not always at hand.

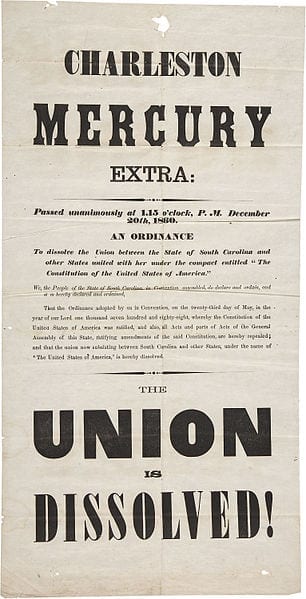

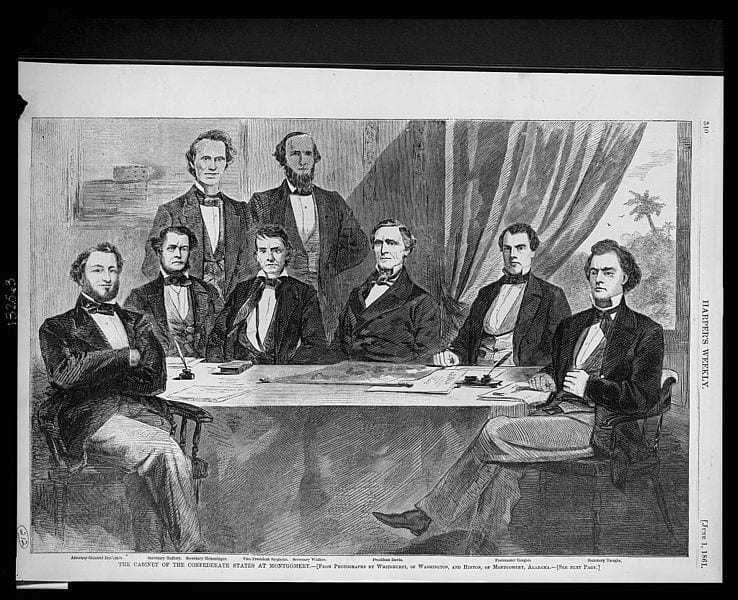

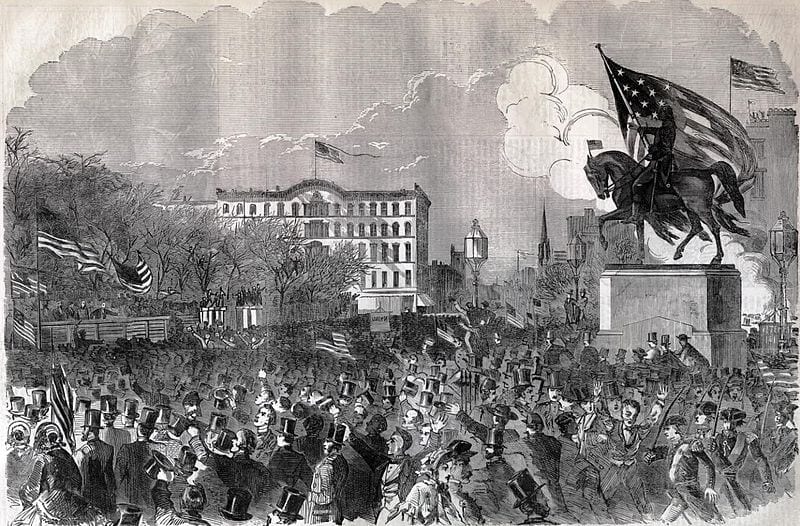

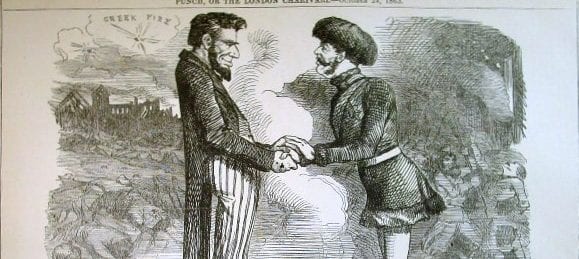

A few moments may be profitably spent in seeking the meaning of each of these terms. Nearly six years ago a bloody war arose between different sections of the United States. Eleven States, possessing a very large extent of territory, and ten or twelve million people, aimed to sever their connection with the Union, and to form an independent empire, founded on the avowed principle of human slavery and excluding every free State from this confederacy. . . . The two powers mutually prepared to settle the question by arms. . . .

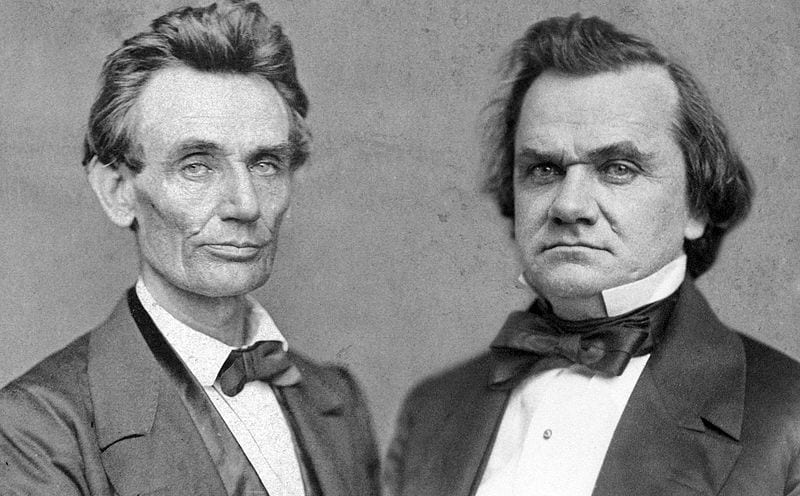

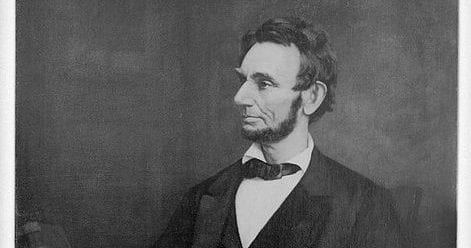

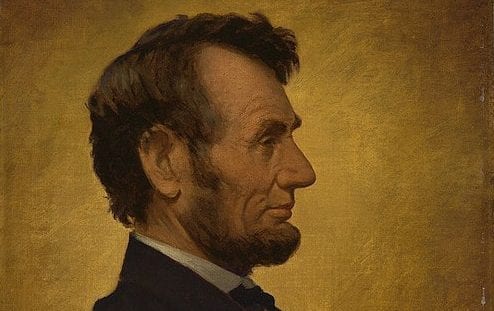

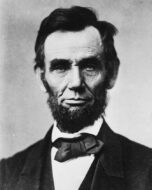

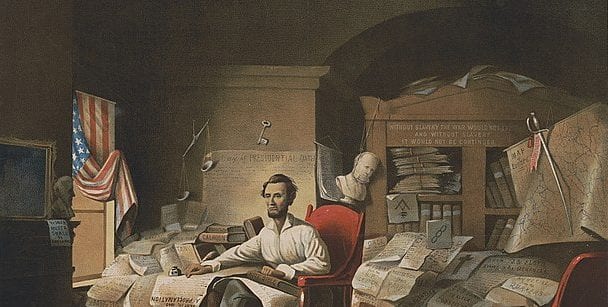

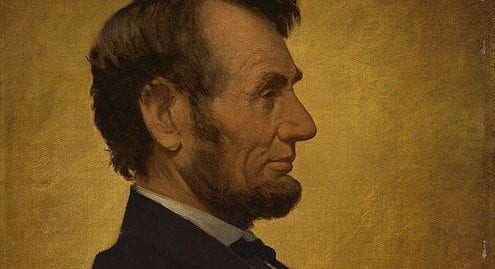

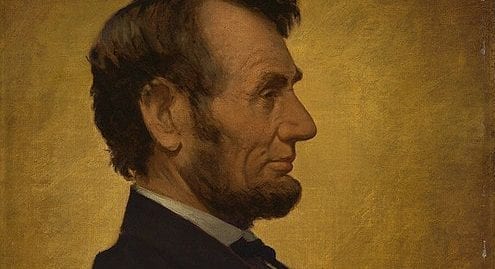

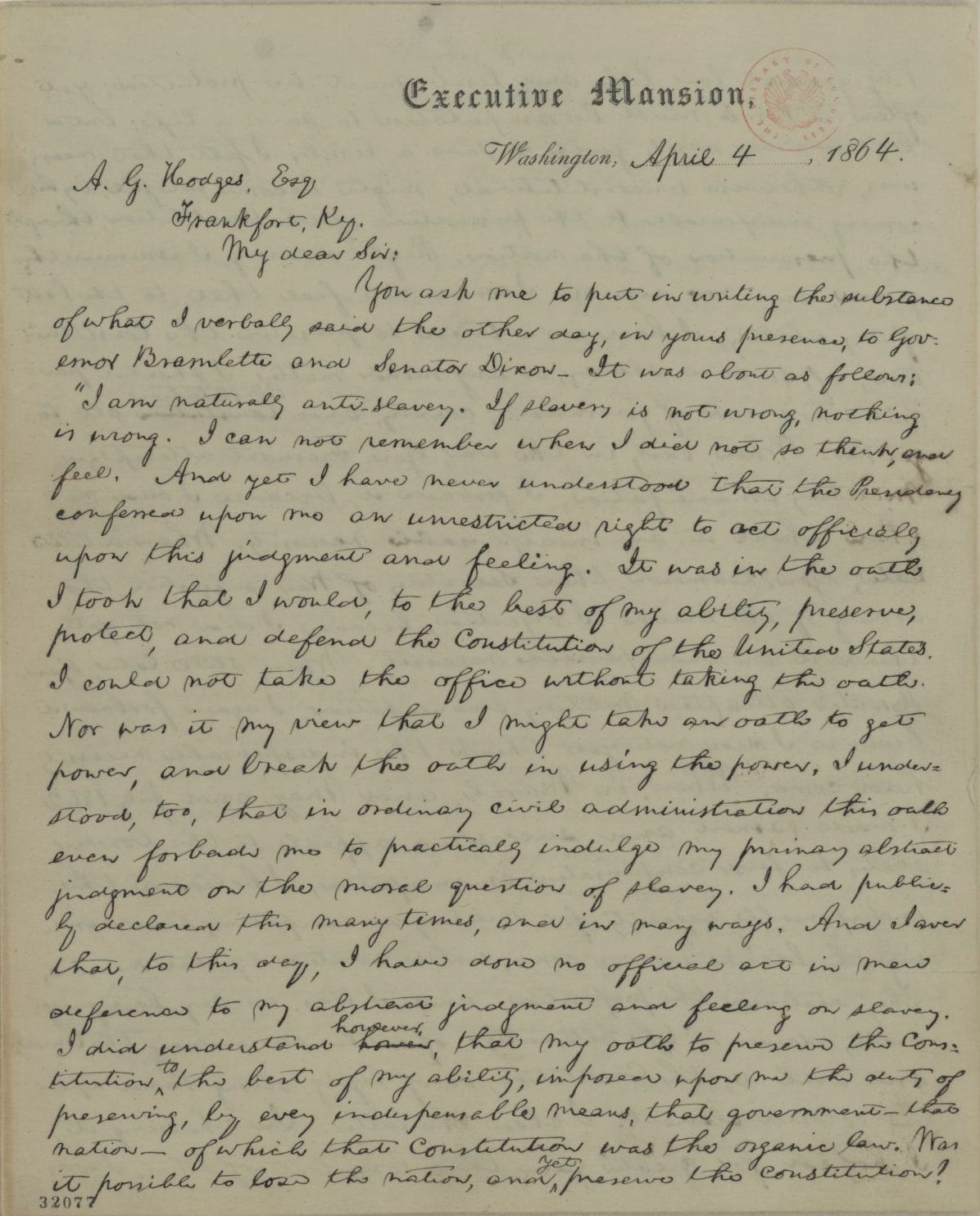

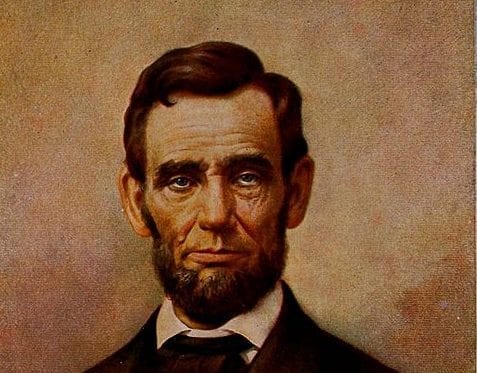

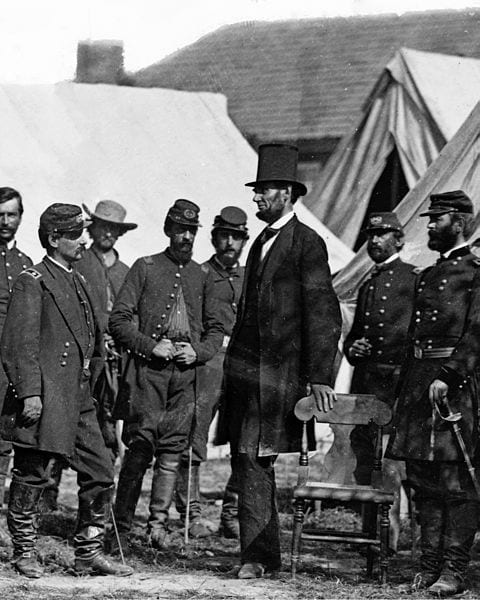

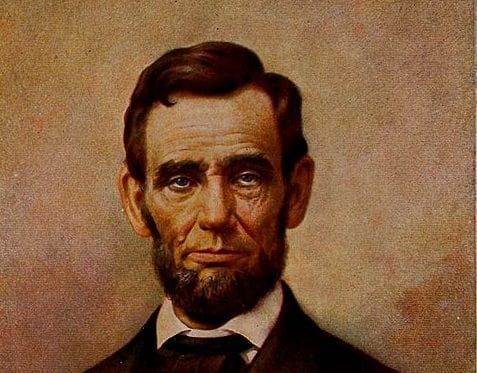

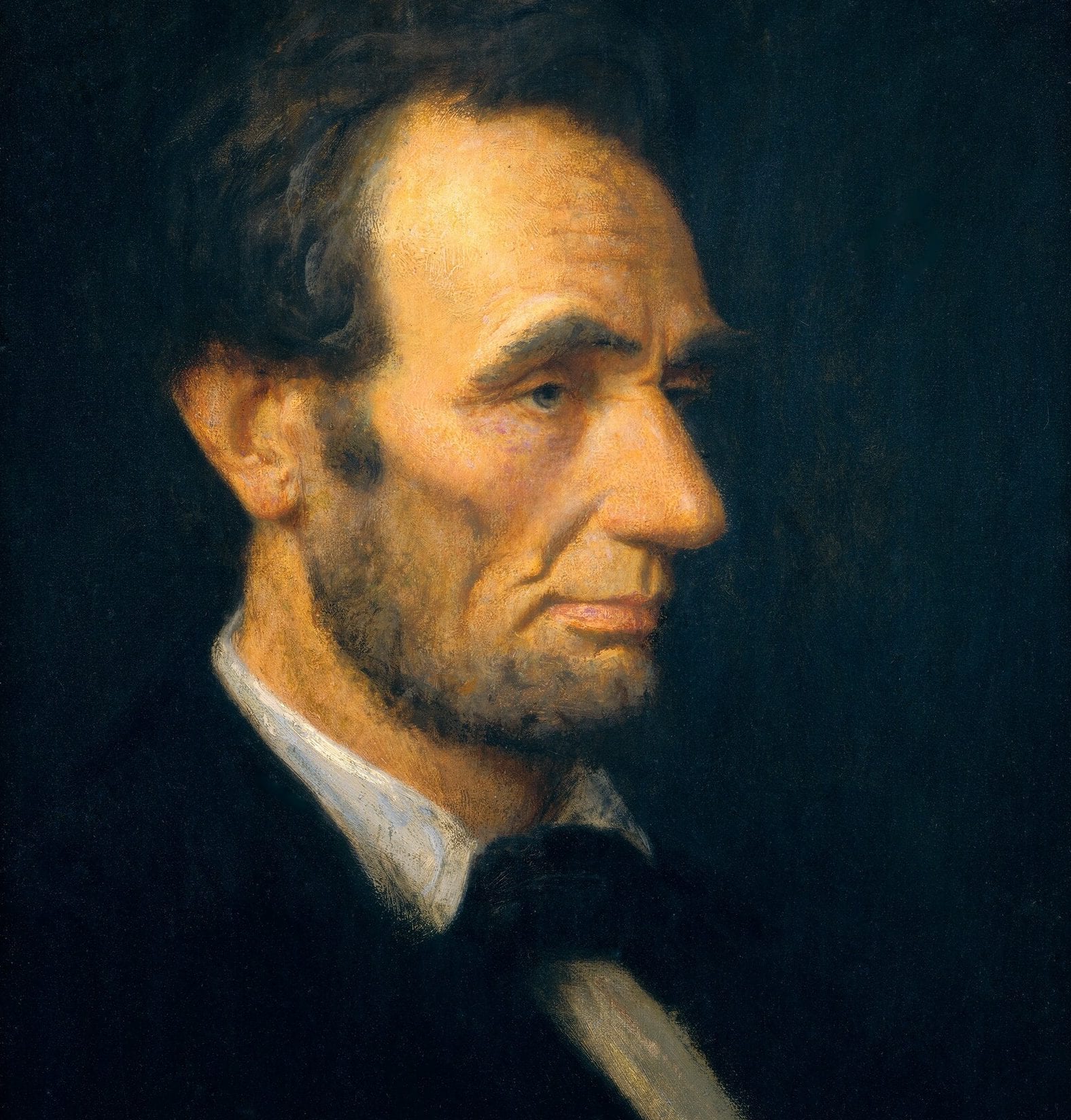

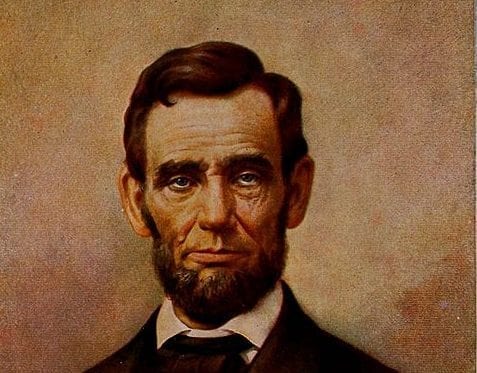

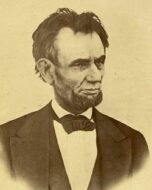

President Lincoln, Vice President Johnson, and both branches of Congress repeatedly declared that the belligerent States could never again intermeddle with the affairs of the Union, or claim any right as members of the United States Government until the legislative power of the Government should declare them entitled thereto. . . . For whether their states were out of the Union as they declared, or were disorganized and “out of their proper relations” to the Government, as some subtle metaphysicians contend, their rights under the Constitution had all been renounced and abjured under oath, and could not be resumed on their own mere motion. . . .

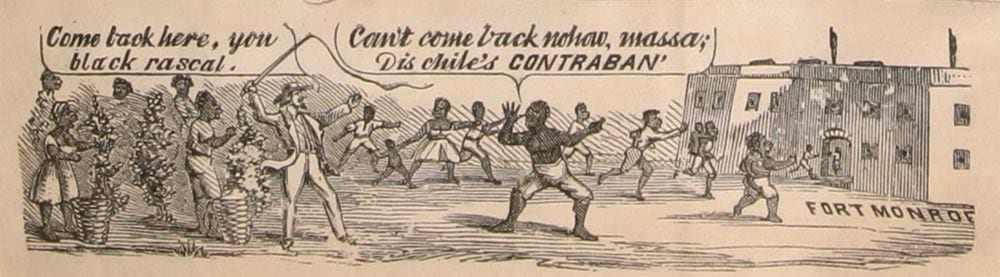

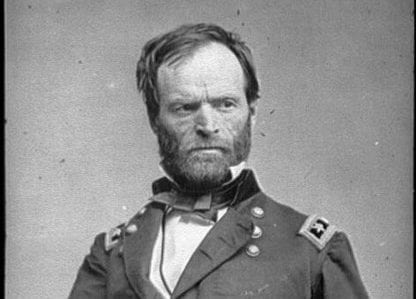

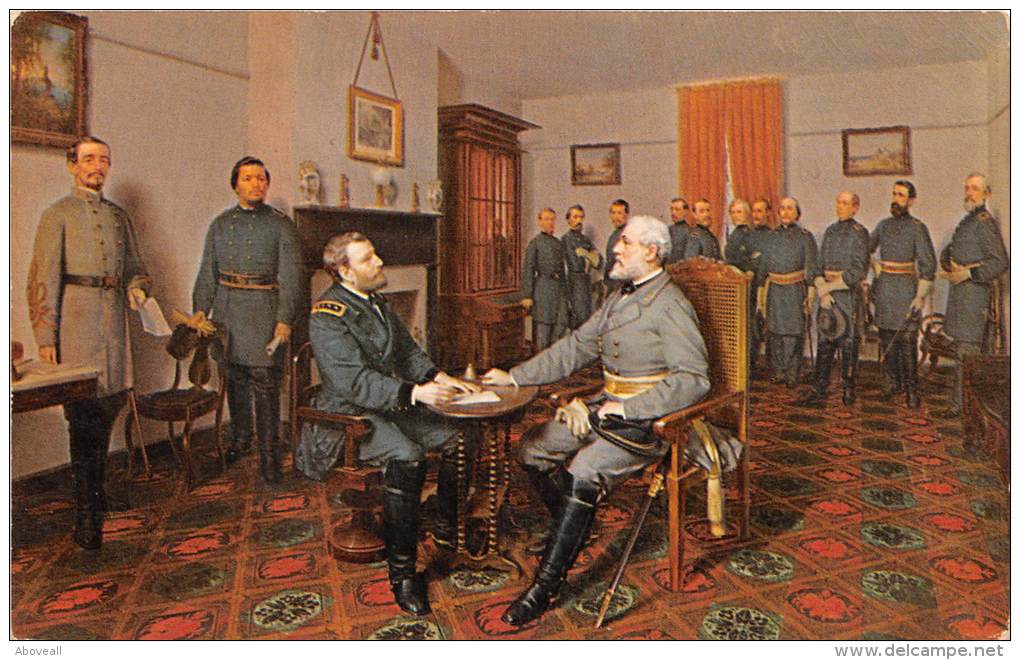

The Federal arms triumphed. The confederate armies and government surrendered unconditionally. The law of nations then fixed their condition. They were subject to the controlling power of the conquerors. No former laws, no former compacts or treaties existed to bind the belligerents. They had all been melted and consumed in the fierce fires of the terrible war. The United States . . . appointed military provisional governors to regulate their municipal institutions until the law-making power of the conqueror should fix their condition and the law by which they should be permanently governed. . . . No one then supposed that those States had any governments, except such as they had formed under their rebel organization. . . . Whoever had then asserted that those States [were] entitled to all the rights and privileges which they enjoyed before the rebellion and were on a level with their loyal conquerors would have been deemed a fool. . . .

In this country the whole sovereignty rests with the people, and is exercised through their Representatives in Congress assembled. . . . No Government official, from the president and the Chief Justice down, can do any one single act which is not prescribed and directed by the legislative power. . . .

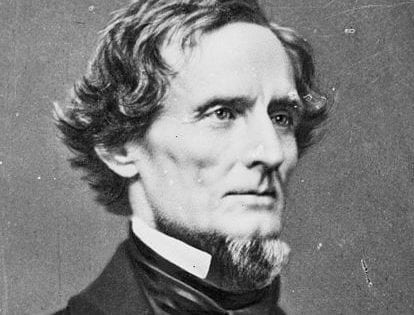

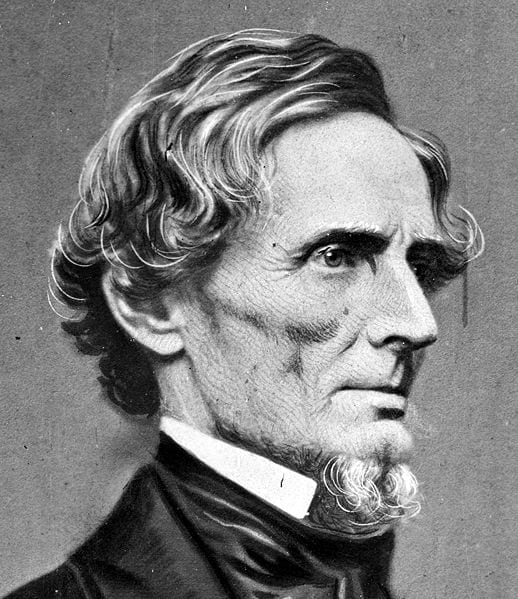

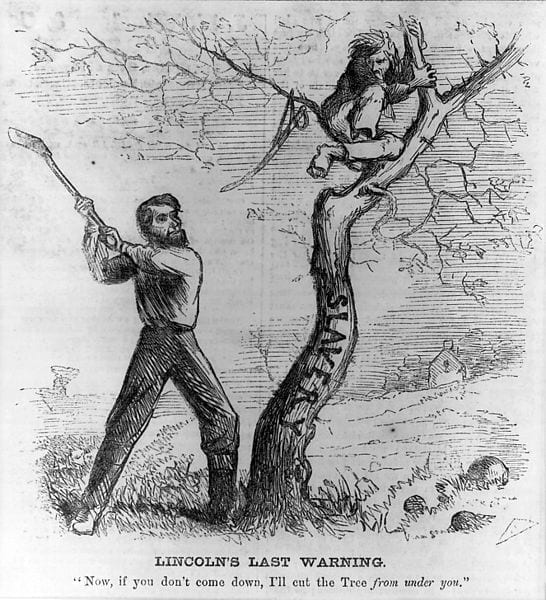

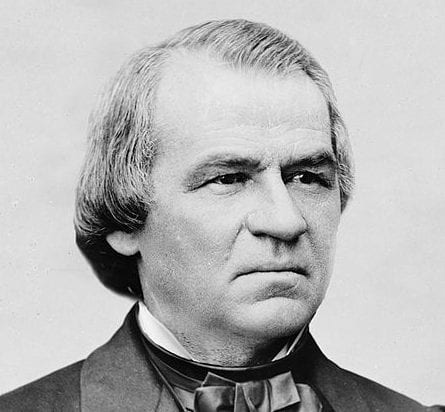

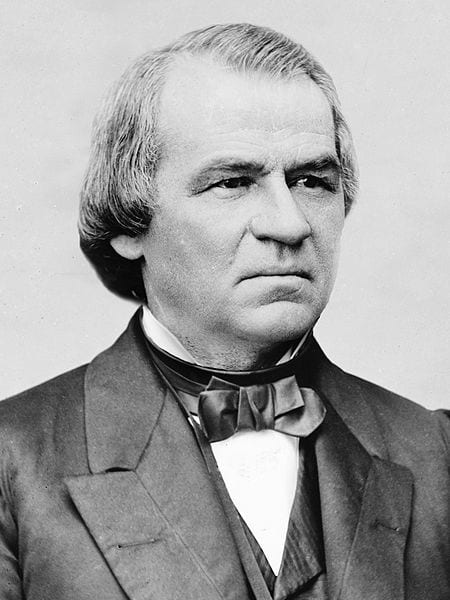

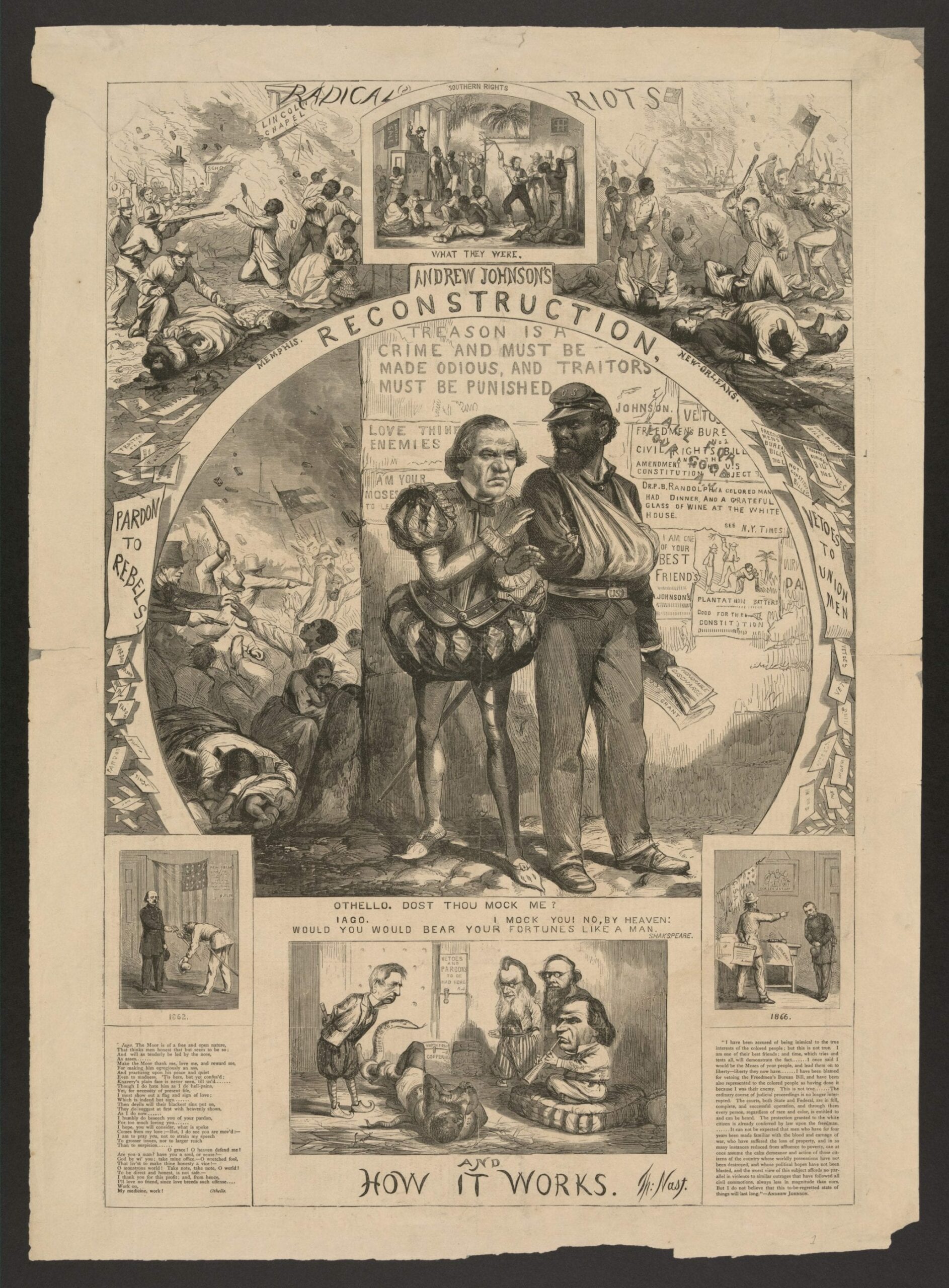

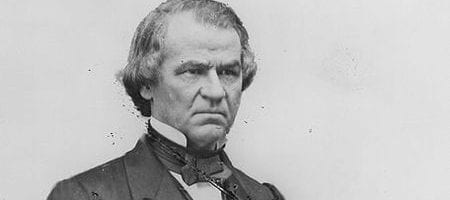

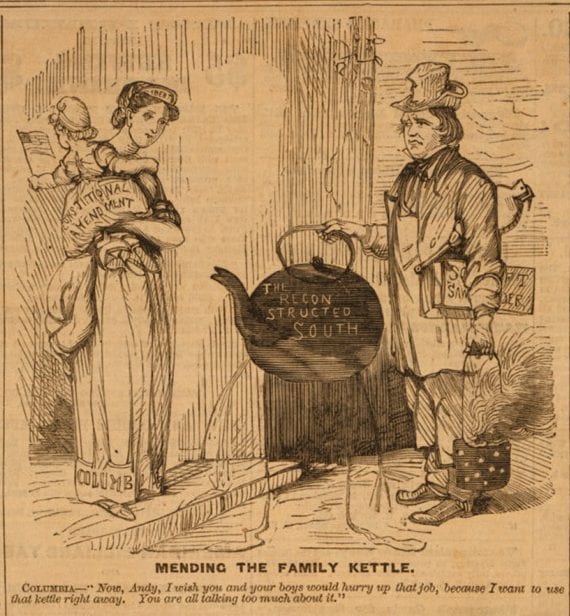

. . . This I take to be the great question between the President and Congress. He claims the right to reconstruct by his own power. Congress denies him all power in the matter, except those of advice, and has determined to maintain such denial. . . .

. . . [President Johnson] desires that the States created by him shall be acknowledged as valid States, while at the same time he inconsistently declares that the old rebel States are in full existence, and always have been, and have equal rights with the loyal States. . . .

Congress refuses to treat the States created by him as of any validity, and denies that the old rebel States have any existence which gives them any rights under the Constitution. . . . Congress denies that any State lately in rebellion has any government or constitution known to the Constitution of the United States . . . .

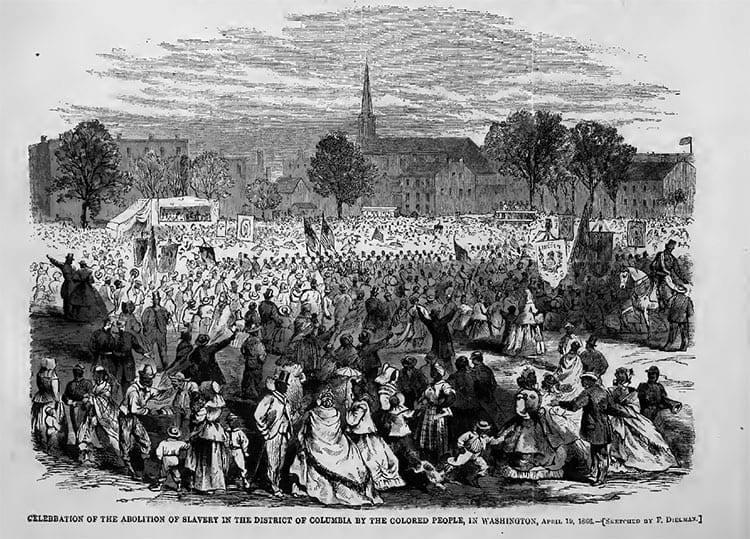

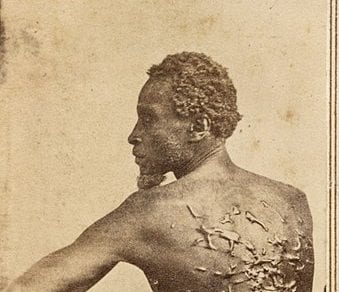

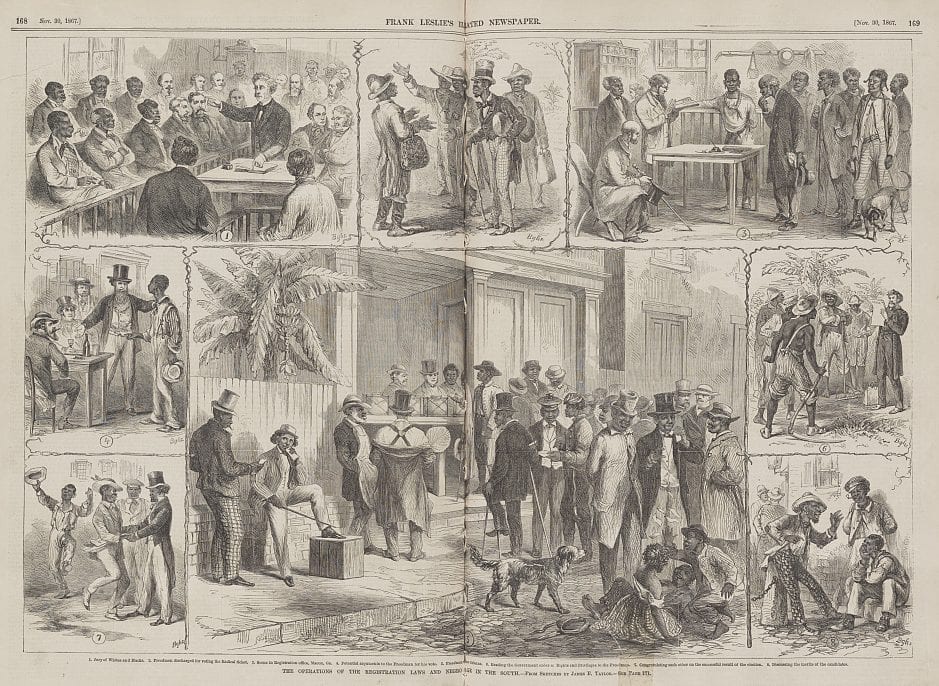

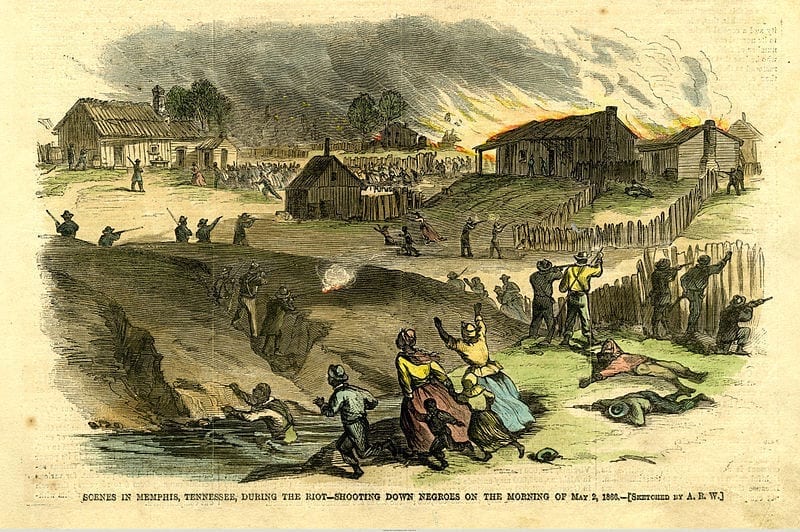

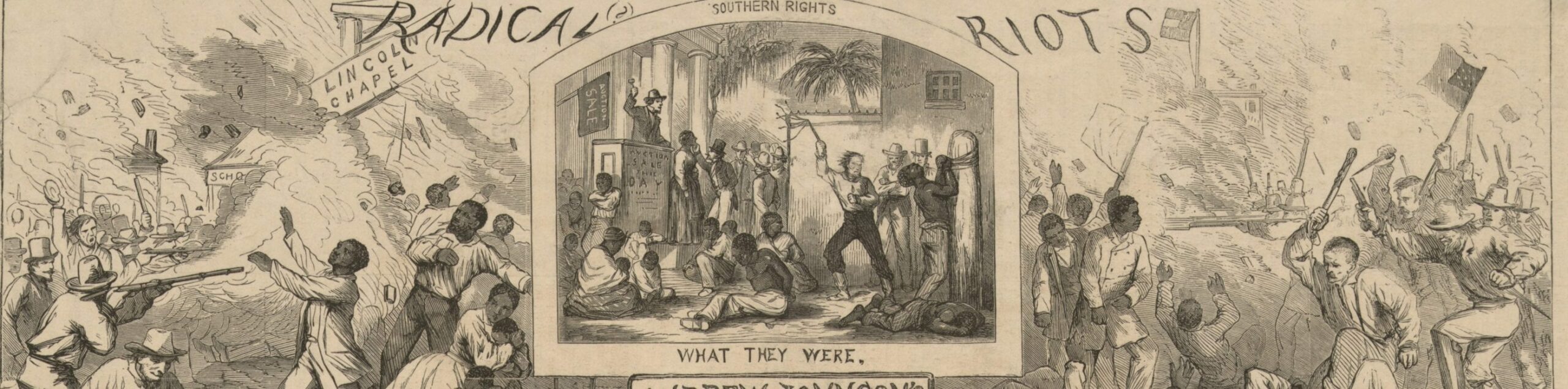

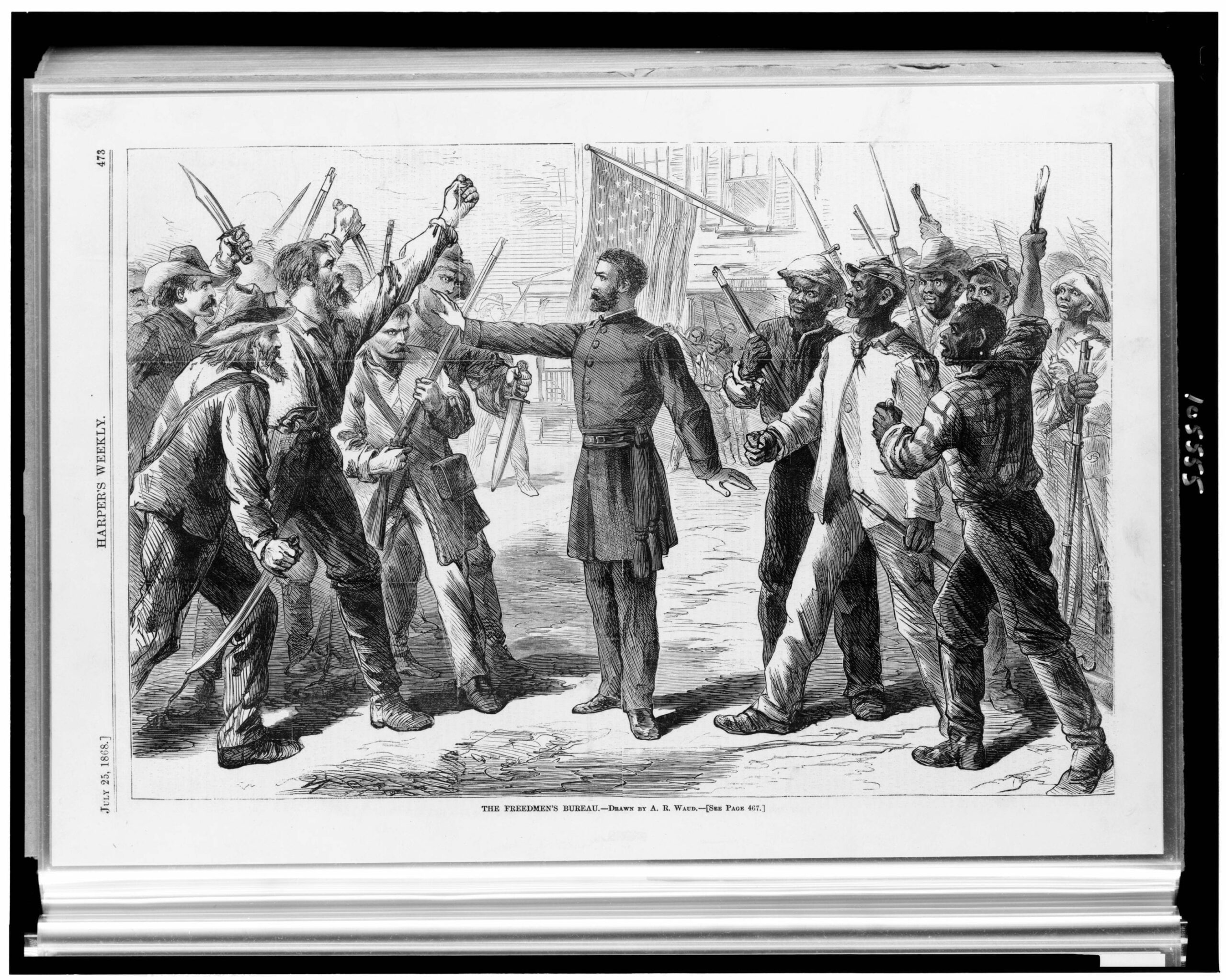

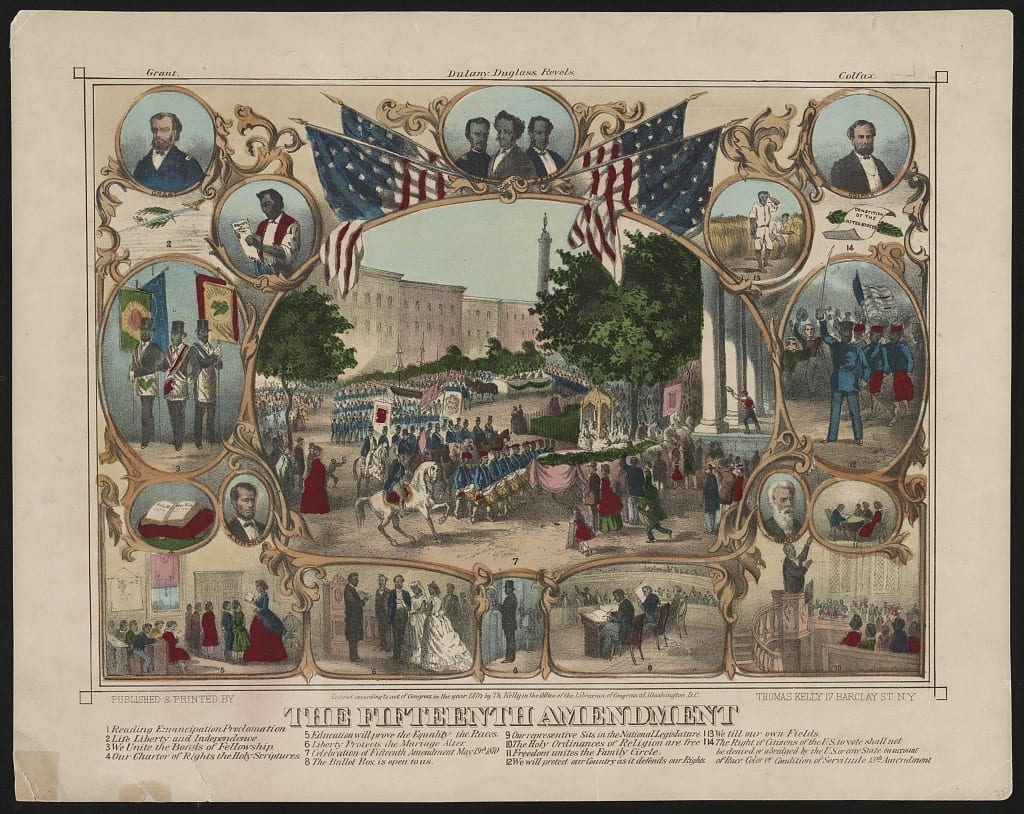

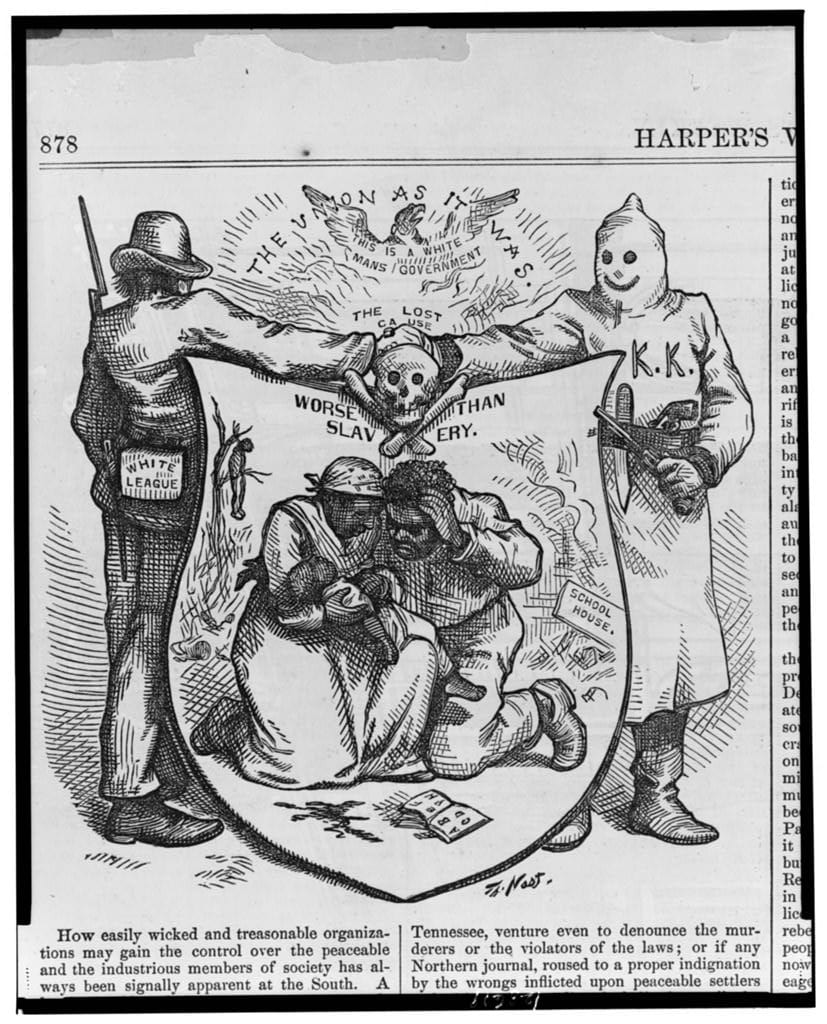

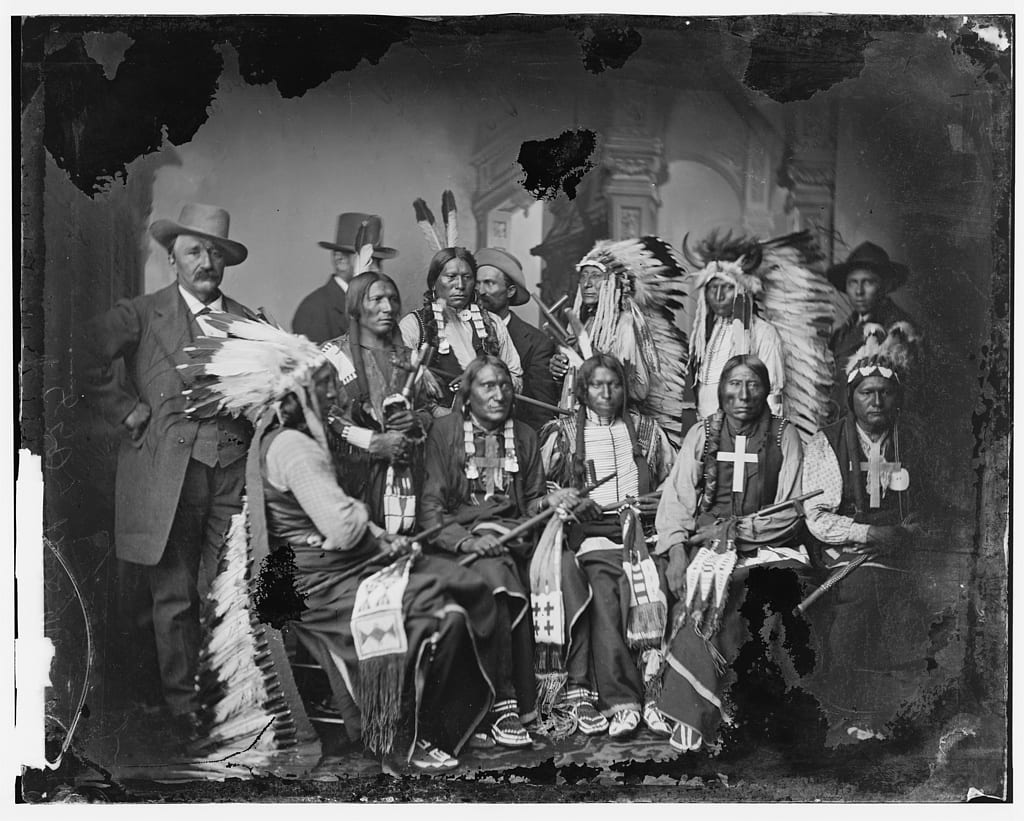

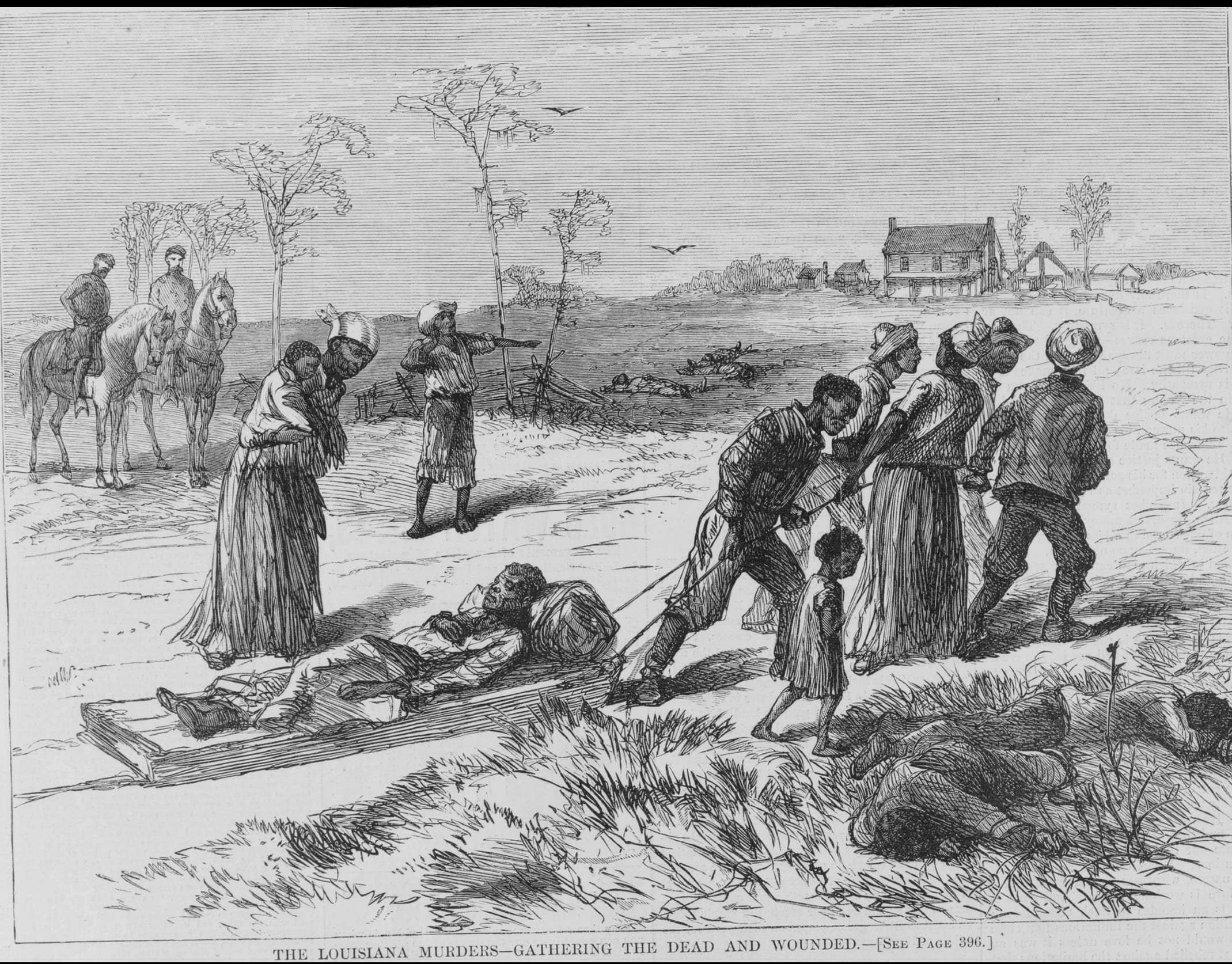

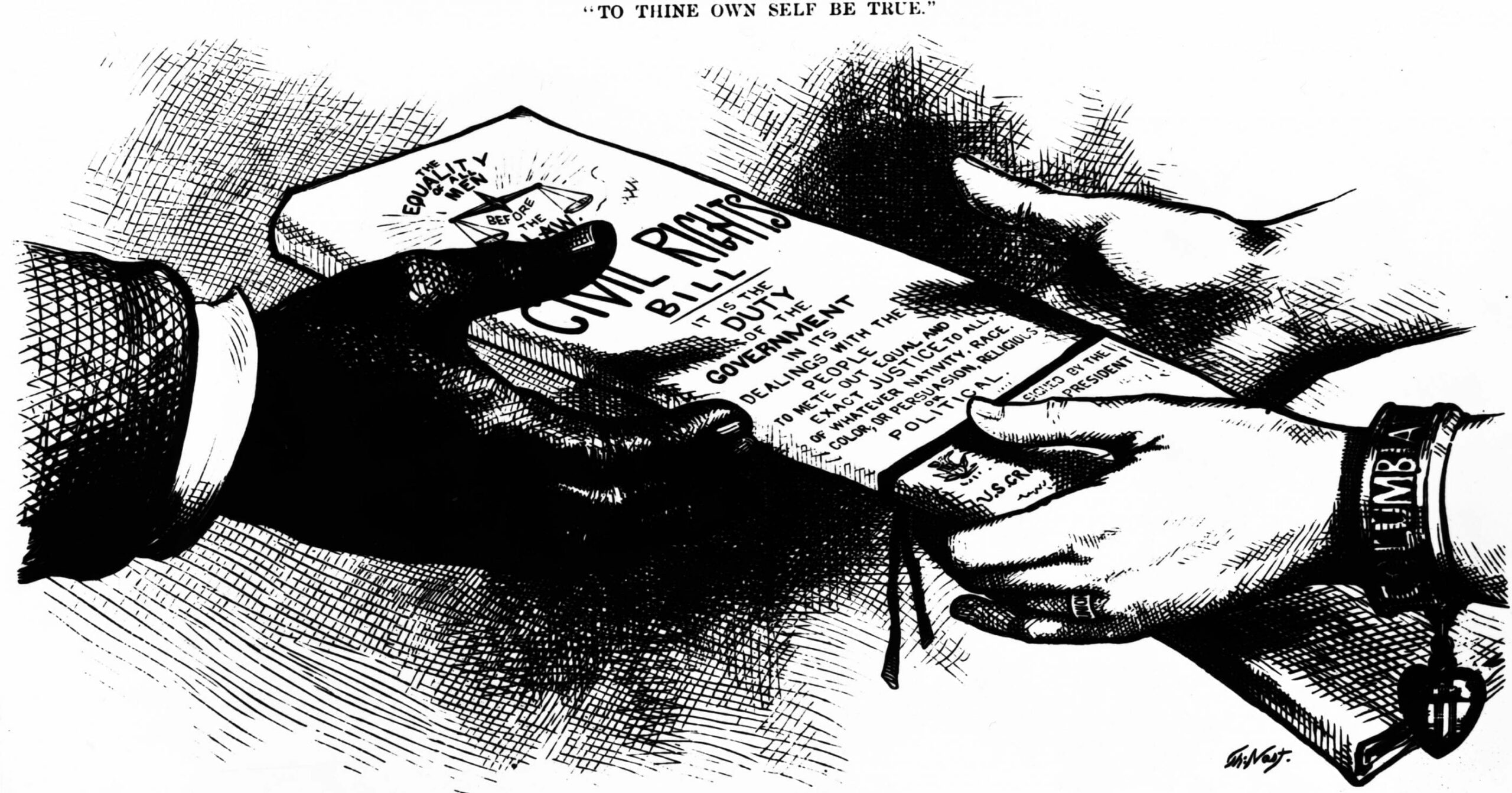

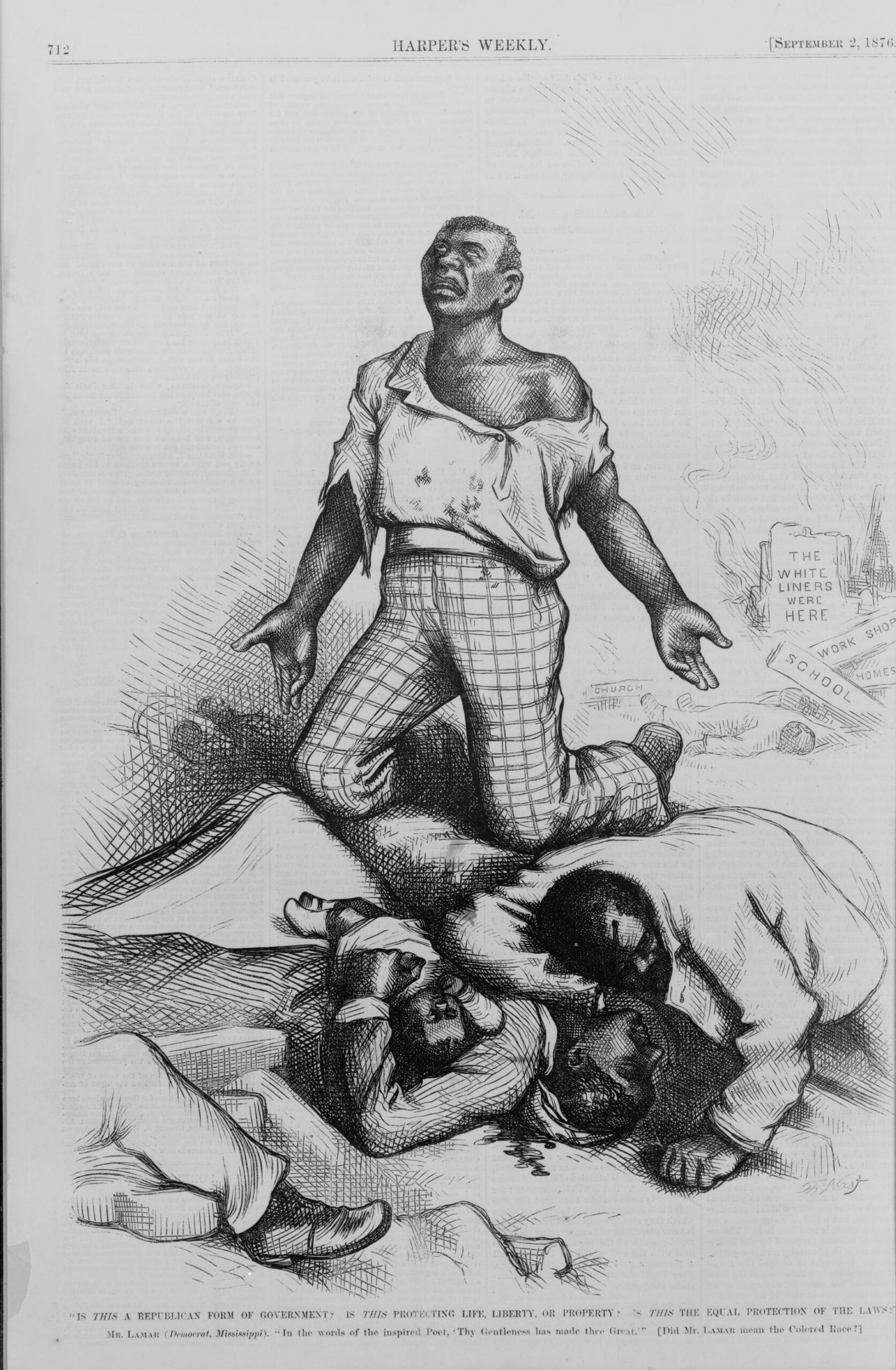

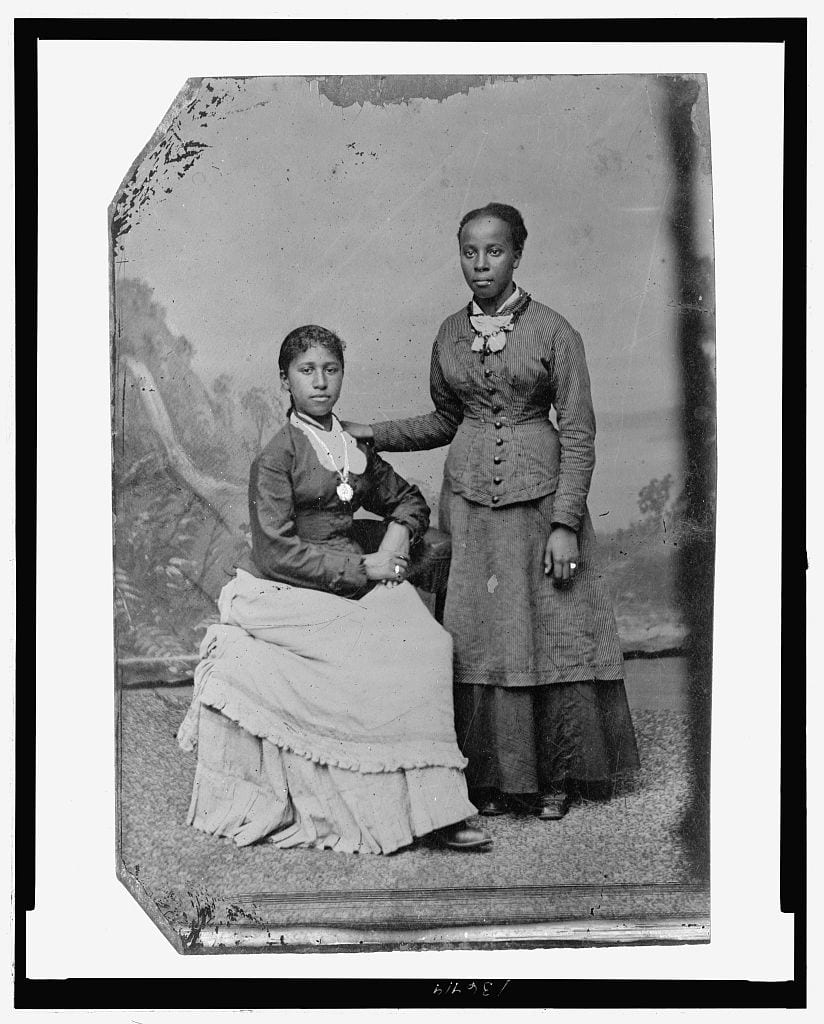

It is to be regretted that inconsiderate[3] and incautious Republicans should ever have supposed that the slight amendments already proposed to the Constitution, even when incorporated into that instrument, would satisfy the reforms necessary for the security of the Government. Unless the rebel States, before admission, should be made republican in spirit, and placed under the guardianship of loyal men, all our blood and treasure will have been spent in vain. I waive now the question of punishment which, if we are wise, will still be inflicted by moderate confiscations, both as a reproof and example. Having these States, as we all agree, entirely within the power of Congress, it is our duty to take care that no injustice shall remain in their organic laws.[4] Holding them “like clay in the hands of the potter,”[5] we must see that no vessel is made for destruction. Having now no governments, they must have enabling acts. . . . Impartial suffrage, both in electing the delegates and ratifying their proceedings, is now the fixed rule. There is more reason why colored voters should be admitted in the rebel States than in the Territories. In the States they form the great mass of the loyal men. Possibly with their aid loyal governments may be established in most of those States. Without it all are sure to be ruled by traitors; and loyal men, black and white, will be oppressed, exiled, or murdered. There are several good reasons for the passage of this bill. In the first place, it is just. I am now confining my arguments to Negro suffrage in the rebel States. Have not loyal blacks quite as good a right to choose rulers and make laws as rebel whites? In the second place, it is a necessity in order to protect the loyal white men in the seceded States. The white Union men are in a great minority in each of those States. With them the blacks would act in a body; and it is believed that in each of said States, except one, the two united would form a majority, control the States, and protect themselves. Now they are the victims of daily murder. They must suffer constant persecution or be exiled. . . . .

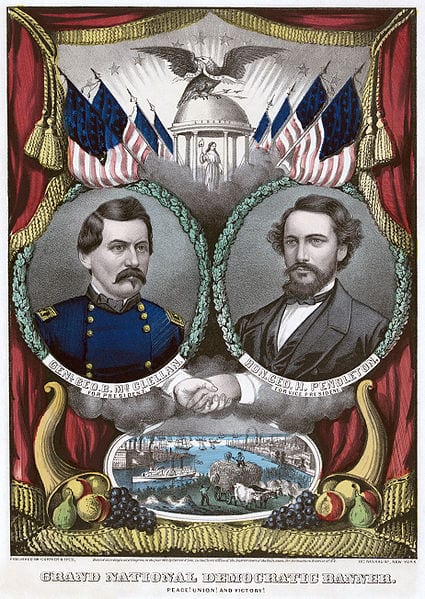

Another good reason is, it would insure the ascendancy of the Union party. Do you avow the party purpose? exclaims some horror-stricken demagogue. I do. For I believe, on my conscience, that on the continued ascendancy of that party depends the safety of this great nation. If impartial suffrage is excluded in the rebel States then everyone of them is sure to send a solid rebel representative delegation to Congress, and cast a solid rebel electoral vote. They, with their kindred Copperheads of the North, would always elect the President and control Congress. While slavery sat upon her defiant throne, and insulted and intimidated the trembling North, the South frequently divided on questions of policy between Whigs and Democrats,[6] and gave victory alternately to the sections. Now, you must divide them between loyalists, without regard to color, and disloyalists, or you will be the perpetual vassals of the free-trade, irritated, revengeful South. For these, among other reasons, I am for Negro suffrage in every rebel State. If it be just, it should not be denied; if it be necessary, it should be adopted; if it be a punishment to traitors, they deserve it.

But it will be said, as it has been said, “This is Negro equality!” What is Negro equality. . .? It means . . . just this much, and no more: every man, no matter what his race or color; every earthly being who has an immortal soul, has an equal right to justice, honesty, and fair play with every other man; and the law should secure him these rights. The same law which condemns or acquits an African should condemn or acquit a white man. The same law which gives a verdict in a White man’s favor should give a verdict in a black man’s favor on the same state of facts. Such is the law of God and such ought to be the law of man. This doctrine does not mean that a Negro shall sit on the same seat or eat at the same table with a white man. That is a matter of taste which every man must decide for himself. . . . If there be any who are afraid of the rivalry of the black man in office or in business, I have only to advise them to try and beat their competitor in knowledge and business capacity, and there is no danger that his white neighbors will prefer his African rival to himself. . . .

- 1. Stevens gives two different numbers for the African American population in the South. Perhaps he refers in the latter instance to African Americans in the nation in general. The 1860 census counted about 4.5 million African Americans residing in the US. About 3.5 million of these lived in the Southern states that would secede, while a half million lived in the border states.

- 2. Copperheads, or Peace Democrats, were those who had opposed war with the South.

- 3. over-hasty; acting without forethought

- 4. the fundamental system of laws or principles that defines the way a nation is governed

- 5. Jeremiah 8:16; Isaiah 64:8.

- 6. The two principal parties in antebellum America, until the Republicans replaced the Whigs.

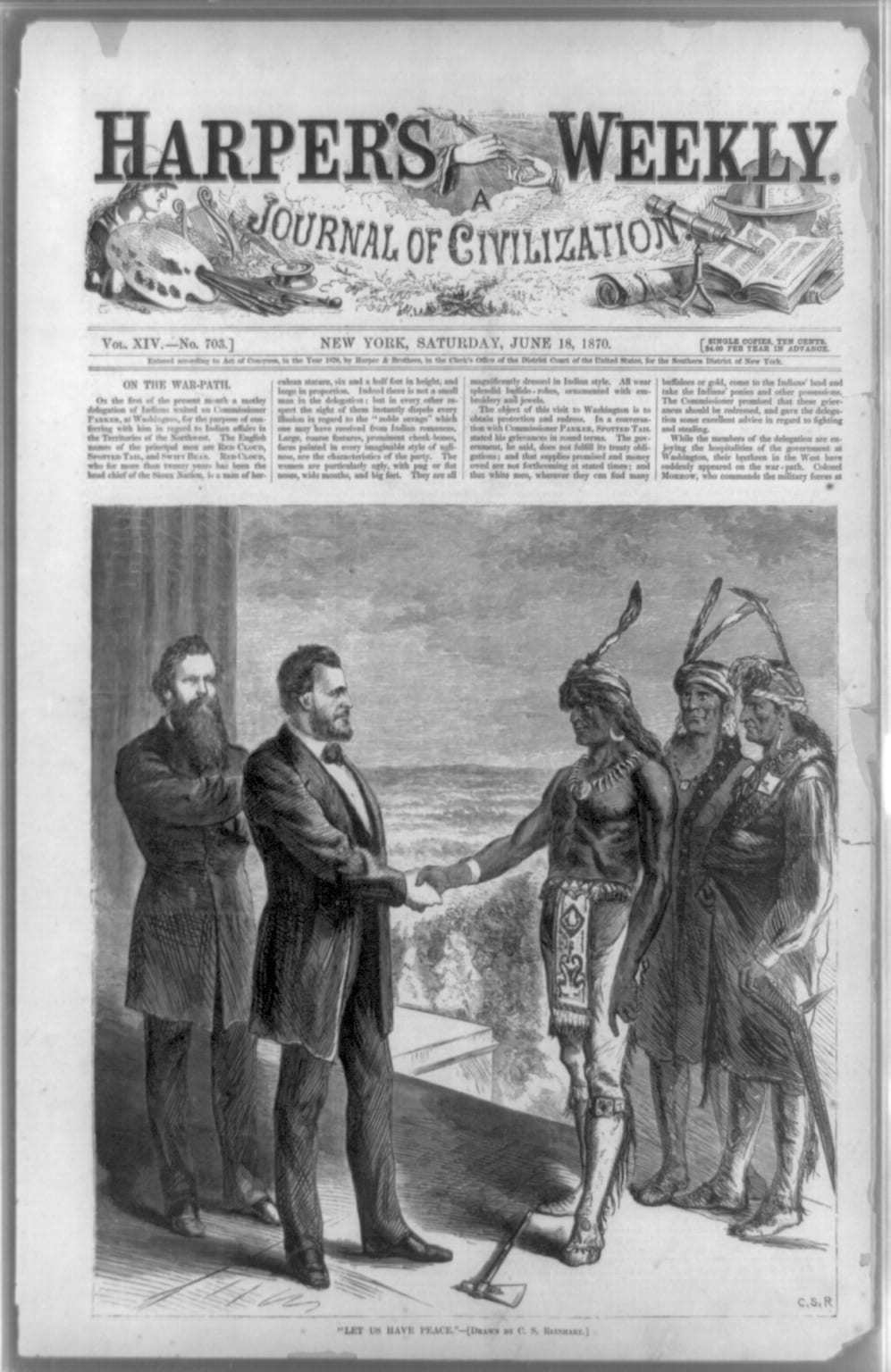

Reconstruction Acts

March 02, 1867

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.