No study questions

No related resources

Introduction

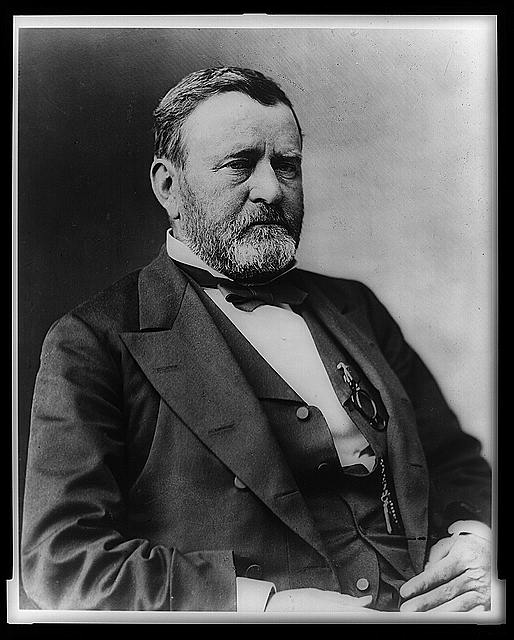

Simon, John Y., "The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 28: November 1, 1876-September 30, 1878" (2005). Volumes of The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. 27. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/usg-volumes/27

To the Senate and House of Representatives:

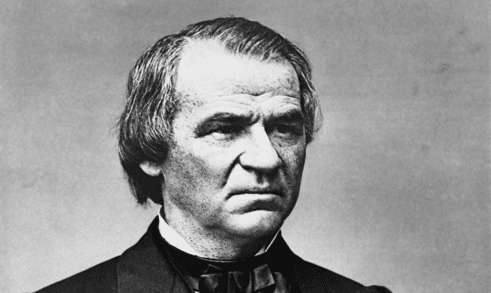

In submitting my eighth and last annual message to Congress it seems proper that I should refer to and in some degree recapitulate the events and official acts of the past eight years.

It was my fortune, or misfortune, to be called to the office of Chief Executive without any previous political training. From the age of 17 I had never even witnessed the excitement attending a Presidential campaign but twice antecedent to my own candidacy, and at but one of them was I eligible as a voter.

Under such circumstances it is but reasonable to suppose that errors of judgment must have occurred. Even had they not, differences of opinion between the Executive, bound by an oath to the strict performance of his duties, and writers and debaters must have arisen. It is not necessarily evidence of blunder on the part of the Executive because there are these differences of views. Mistakes have been made, as all can see and I admit, but it seems to me oftener in the selections made of the assistants appointed to aid in carrying out the various duties of administering the Government—in nearly every case selected without a personal acquaintance with the appointee, but upon recommendations of the representatives chosen directly by the people. It is impossible, where so many trusts are to be allotted, that the right parties should be chosen in every instance. History shows that no Administration from the time of Washington to the present has been free from these mistakes. But I leave comparisons to history, claiming only that I have acted in every instance from a conscientious desire to do what was right, constitutional, within the law, and for the very best interests of the whole people. Failures have been errors of judgment, not of intent.

My civil career commenced, too, at a most critical and difficult time. Less than four years before, the country had emerged from a conflict such as no other nation had ever survived. Nearly one-half of the States had revolted against the Government, and of those remaining faithful to the Union a large percentage of the population sympathized with the rebellion and made an "enemy in the rear" almost as dangerous as the more honorable enemy in the front. The latter committed errors of judgment, but they maintained them openly and courageously; the former received the protection of the Government they would see destroyed, and reaped all the pecuniary advantage to be gained out of the then existing state of affairs, many of them by obtaining contracts and by swindling the Government in the delivery of their goods.

Immediately on the cessation of hostilities the then noble President, who had carried the country so far through its perils, fell a martyr to his patriotism at the hands of an assassin.

The intervening time to my first inauguration was filled up with wranglings between Congress and the new Executive as to the best mode of "reconstruction," or, to speak plainly, as to whether the control of the Government should be thrown immediately into the hands of those who had so recently and persistently tried to destroy it, or whether the victors should continue to have an equal voice with them in this control. Reconstruction, as finally agreed upon, means this and only this, except that the late slave was enfranchised, giving an increase, as was supposed, to the Union-loving and Union-supporting votes. If free in the full sense of the word, they would not disappoint this expectation. Hence at the beginning of my first Administration the work of reconstruction, much embarrassed by the long delay, virtually commenced. It was the work of the legislative branch of the Government. My province was wholly in approving their acts, which I did most heartily, urging the legislatures of States that had not yet done so to ratify the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution. The country was laboring under an enormous debt, contracted in the suppression of rebellion, and taxation was so oppressive as to discourage production. Another danger also threatened us—a foreign war. The last difficulty had to be adjusted and was adjusted without a war and in a manner highly honorable to all parties concerned. Taxes have been reduced within the last seven years nearly $300,000,000, and the national debt has been reduced in the same time over $435,000,000. By refunding the 6 per cent bonded debt for bonds bearing 5 and 4 1/2 per cent interest, respectively, the annual interest has been reduced from over $130,000,000 in 1869 to but little over $100,000,000 in 1876. The balance of trade has been changed from over $130,000,000 against the United States in 1869 to more than $120,000,000 in our favor in 1876.

It is confidently believed that the balance of trade in favor of the United States will increase, not diminish, and that the pledge of Congress to resume specie payments in 1879 will be easily accomplished, even in the absence of much-desired further legislation on the subject.

A policy has been adopted toward the Indian tribes inhabiting a large portion of the territory of the United States which has been humane and has substantially ended Indian hostilities in the whole land except in a portion of Nebraska, and Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana Territories—the Black Hills region and approaches thereto. Hostilities there have grown out of the avarice of the white man, who has violated our treaty stipulations in his search for gold. The question might be asked why the Government has not enforced obedience to the terms of the treaty prohibiting the occupation of the Black Hills region by whites. The answer is simple: The first immigrants to the Black Hills were removed by troops, but rumors of rich discoveries of gold took into that region increased numbers. Gold has actually been found in paying quantity, and an effort to remove the miners would only result in the desertion of the bulk of the troops that might be sent there to remove them. All difficulty in this matter has, however, been removed—subject to the approval of Congress—by a treaty ceding the Black Hills and approaches to settlement by citizens.

The subject of Indian policy and treatment is so fully set forth by the Secretary of the Interior and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and my views so fully expressed therein, that I refer to their reports and recommendations as my own.

The relations of the United States with foreign powers continue on a friendly footing.

Questions have arisen from time to time in the foreign relations of the Government, but the United States have been happily free during the past year from the complications and embarrassments which have surrounded some of the foreign powers.

The diplomatic correspondence submitted herewith contains information as to certain of the matters which have occupied the Government.

The cordiality which attends our relations with the powers of the earth has been plainly shown by the general participation of foreign nations in the exhibition which has just closed and by the exertions made by distant powers to show their interest in and friendly feelings toward the United States in the commemoration of the centennial of the nation. The Government and people of the United States have not only fully appreciated this exhibition of kindly feeling, but it may be justly and fairly expected that no small benefits will result both to ourselves and other nations from a better acquaintance, and a better appreciation of our mutual advantages and mutual wants.

Congress at its last session saw fit to reduce the amount usually appropriated for foreign intercourse by withholding appropriations for representatives of the United States in certain foreign countries and for certain consular officers, and by reducing the amounts usually appropriated for certain other diplomatic posts, and thus necessitating a change in the grade of the representatives. For these reasons, immediately upon the passage of the bill making appropriations for the diplomatic and consular service for the present fiscal year, instructions were issued to the representatives of the United States at Bolivia, Ecuador, and Colombia, and to the consular officers for whom no appropriation had been made, to close their respective legations and consulates and cease from the performance of their duties; and in like manner steps were immediately taken to substitute charge’s d’affaires for ministers resident in Portugal, Denmark, Greece, Switzerland, and Paraguay.

While thoroughly impressed with the wisdom of sound economy in the foreign service, as in other branches of the Government, I can not escape the conclusion that in some instances the withholding of appropriations will prove an expensive economy, and that the small retrenchment secured by a change of grade in certain diplomatic posts is not an adequate consideration for the loss of influence and importance which will attend our foreign representatives under this reduction. I am of the opinion that a reexamination of the subject will cause a change in some instances in the conclusions reached on these subjects at the last session of Congress.

The Court of Commissioners of Alabama Claims, whose functions were continued by an act of the last session of Congress until the 1st day of January, 1877, has carried on its labors with diligence and general satisfaction. By a report from the clerk of the court, transmitted herewith, bearing date November 14, 1876, it appears that within the time now allowed by law the court will have disposed of all the claims presented for adjudication. This report also contains a statement of the general results of the labors of the court to the date thereof. It is a cause of satisfaction that the method adopted for the satisfaction of the classes of claims submitted to the court, which are of long standing and justly entitled to early consideration, should have proved successful and acceptable.

It is with satisfaction that I am enabled to state that the work of the joint commission for determining the boundary line between the United States and British possessions from the northwest angle of the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains, commenced in 1872, has been completed. The final agreements of the commissioners, with the maps, have been duly signed, and the work of the commission is complete.

The fixing of the boundary upon the Pacific coast by the protocol of March 10, 1873, pursuant to the award of the Emperor of Germany by Article XXXIV of the treaty of Washington, with the termination of the work of this commission, adjusts and fixes the entire boundary between the United States and the British possessions, except as to the portion of territory ceded by Russia to the United States under the treaty of 1867. The work intrusted to the commissioner and the officers of the Army attached to the commission has been well and satisfactorily performed. The original of the final agreement of the commissioners, signed upon the 29th of May, 1876, with the original official "lists of astronomical stations observed," the original official "list of monuments marking the international boundary line," and the maps, records, and general reports relating to the commission, have been deposited in the Department of State. The official report of the commissioner on the part of the United States, with the report of the chief astronomer of the United States, will be submitted to Congress within a short time.

I reserve for a separate communication to Congress a statement of the condition of the questions which lately arose with Great Britain respecting the surrender of fugitive criminals under the treaty of 1842.

The Ottoman Government gave notice, under date of January 15, 1874, of its desire to terminate the treaty of 1862, concerning commerce and navigation, pursuant to the provisions of the twenty-second article thereof. Under this notice the treaty terminated upon the 5th day of June, 1876. That Government has invited negotiations toward the conclusion of a new treaty.

By the act of Congress of March 23, 1874, the President was authorized, when he should receive satisfactory information that the Ottoman Government or that of Egypt had organized new tribunals likely to secure to citizens of the United States the same impartial justice enjoyed under the exercise of judicial functions by diplomatic and consular officers of the United States, to suspend the operation of the act of June 22, 1860, and to accept for citizens of the United States the jurisdiction of the new tribunals. Satisfactory information having been received of the organization of such new tribunals in Egypt, I caused a proclamation to be issued upon the 27th of March last, suspending the operation of the act of June 22, 1860, in Egypt, according to the provisions of the act. A copy of the proclamation accompanies this message. The United States has united with the other powers in the organization of these courts. It is hoped that the jurisdictional questions which have arisen may be readily adjusted, and that this advance in judicial reform may be hindered by no obstacles.

The necessary legislation to carry into effect the convention respecting commercial reciprocity concluded with the Hawaiian Islands in 1875 having been had, the proclamation to carry into effect the convention, as provided by the act approved August 15, 1876, was duly issued upon the 9th day of September last. A copy thereof accompanies this message.

The commotions which have been prevalent in Mexico for some time past, and which, unhappily, seem to be not yet wholly quieted, have led to complaints of citizens of the United States of injuries by persons in authority. It is hoped, however, that these will ultimately be adjusted to the satisfaction of both Governments. The frontier of the United States in that quarter has not been exempt from acts of violence by citizens of one Republic on those of the other. The frequency of these is supposed to be increased and their adjustment made more difficult by the considerable changes in the course of the lower part of the Rio Grande River, which river is a part of the boundary between the two countries. These changes have placed on either side of that river portions of land which by existing conventions belong to the jurisdiction of the Government on the opposite side of the river. The subject of adjustment of this cause of difficulty is under consideration between the two Republics.

The Government of the United States of Colombia has paid the award in the case of the steamer Montijo, seized by authorities of that Government some years since, and the amount has been transferred to the claimants.

It is with satisfaction that I am able to announce that the joint commission for the adjustment of claims between the United States and Mexico under the convention of 1868, the duration of which has been several times extended, has brought its labors to a close. From the report of the agent of the United States, which accompanies the papers transmitted herewith, it will be seen that within the time limited by the commission 1,017 claims on the part of citizens of the United States against Mexico were referred to the commission. Of these claims 831 were dismissed or disallowed, and in 186 cases awards were made in favor of the claimants against the Mexican Republic, amounting in the aggregate to $4,125,622.20. Within the same period 998 claims on the part of citizens of the Mexican Republic against the United States were referred to the commission. Of these claims 831 were dismissed or disallowed, and in 167 cases awards were made in favor of the claimants against the United States, amounting in the aggregate to $150,498.41.

By the terms of the convention the amount of these awards is to be deducted from the amount awarded in favor of our citizens against Mexico, and the balance only to be paid by Mexico to the United States, leaving the United States to make provision for this proportion of the awards in favor of its Own citizens.

I invite your attention to the legislation which will be necessary to provide for the payment.

In this connection I am pleased to be able to express the acknowledgments due to Sir Edward Thornton, the umpire of the commission, who has given to the consideration of the large number of claims submitted to him much time, unwearied patience, and that firmness and intelligence which are well known to belong to the accomplished representative of Great Britain, and which are likewise recognized by the representative in this country of the Republic of Mexico.

Monthly payments of a very small part of the amount due by the Government of Venezuela to citizens of the United States on account of claims of the latter against that Government continue to be made with reasonable punctuality. That Government has proposed to change the system which it has hitherto pursued in this respect by issuing bonds for part of the amount of the several claims. The proposition, however, could not, it is supposed, properly be accepted, at least without the consent of the holders of certificates of the indebtedness of Venezuela. These are so much dispersed that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain their disposition on the subject.

In former messages I have called the attention of Congress to the necessity of legislation with regard to fraudulent naturalization and to the subject of expatriation and the election of nationality.

The numbers of persons of foreign birth seeking a home in the United States, the ease and facility with which the honest emigrant may, after the lapse of a reasonable time, become possessed of all the privileges of citizenship of the United States, and the frequent occasions which induce such adopted citizens to return to the country of their birth render the subject of naturalization and the safeguards which experience has proved necessary for the protection of the honest naturalized citizen of paramount importance. The very simplicity in the requirements of law on this question affords opportunity for fraud, and the want of uniformity in the proceedings and records of the various courts and in the forms of the certificates of naturalization issued affords a constant source of difficulty.

I suggest no additional requirements to the acquisition of citizenship beyond those now existing, but I invite the earnest attention of Congress to the necessity and wisdom of some provisions regarding uniformity in the records and certificates, and providing against the frauds which frequently take place and for the vacating of a record of naturalization obtained in fraud.

These provisions are needed in aid and for the protection of the honest citizen of foreign birth, and for the want of which he is made to suffer not infrequently. The United States has insisted upon the right of expatriation, and has obtained, after a long struggle, an admission of the principle contended for by acquiescence therein on the part of many foreign powers and by the conclusion of treaties on that subject. It is, however, but justice to the government to which such naturalized citizens have formerly owed allegiance, as well as to the United States, that certain fixed and definite rules should be adopted governing such cases and providing how expatriation may be accomplished.

While emigrants in large numbers become citizens of the United States, it is also true that persons, both native born and naturalized, once citizens of the United States, either by formal acts or as the effect of a series of facts and circumstances, abandon their citizenship and cease to be entitled to the protection of the United States, but continue on convenient occasions to assert a claim to protection in the absence of provisions on these questions.

And in this connection I again invite your attention to the necessity of legislation concerning the marriages of American citizens contracted abroad, and concerning the status of American women who may marry foreigners and of children born of American parents in a foreign country.

The delicate and complicated questions continually occurring with reference to naturalization, expatriation, and the status of such persons as I have above referred to induce me to earnestly direct your attention again to these subjects.

In like manner I repeat my recommendation that some means be provided for the hearing and determination of the just and subsisting claims of aliens upon the Government of the United States within a reasonable limitation,and of such as may hereafter arise. While by existing provisions of law the Court of Claims may in certain cases be resorted to by an alien claimant, the absence of any general provisions governing all such cases and the want of a tribunal skilled in the disposition of such cases upon recognized fixed and settled principles, either provides no remedy in many deserving cases or compels a consideration of such claims by Congress or the executive department of the Government.

It is believed that other governments are in advance of the United States upon this question, and that the practice now adopted is entirely unsatisfactory.

Congress, by an act approved the 3d day of March, 1875, authorized the inhabitants of the Territory of Colorado to form a State government, with the name of the State of Colorado, and therein provided for the admission of said State, when formed, into the Union upon an equal footing with the original States.

A constitution having been adopted and ratified by the people of that State, and the acting governor having certified to me the facts as provided by said act, together with a copy of such constitution and ordinances as provided for in the said act, and the provisions of the said act of Congress having been duly complied with, I issued a proclamation upon the 1st of August, 1876, a copy of which is hereto annexed.

The report of the Secretary of War shows that the Army has been actively employed during the year in subduing, at the request of the Indian Bureau, certain wild bands of the Sioux Indian Nation and in preserving the peace at the South during the election. The commission constituted under the act of July 24, 1876, to consider and report on the "whole subject of the reform and reorganization of the Army" met in August last, and has collected a large mass of statistics and opinions bearing on the subject before it. These are now under consideration, and their report is progressing. I am advised, though, by the president of the commission that it will be impracticable to comply with the clause of the act requiring the report to be presented, through me, to Congress on the first day of this session, as there has not yet been time for that mature deliberation which the importance of the subject demands. Therefore I ask that the time of making the report be extended to the 29th day of January, 1877.

In accordance with the resolution of August 15, 1876, the Army regulations prepared under the act of March 1, 1875, have not been promulgated, but are held until after the report of the above-mentioned commission shall have been received and acted on.

By the act of August 15, 1876, the cavalry force of the Army was increased by 2,500 men, with the proviso that they should be discharged on the expiration of hostilities. Under this authority the cavalry regiments have been strengthened, and a portion of them are now in the field pursuing the remnants of the Indians with whom they have been engaged during the summer.

The estimates of the War Department are made up on the basis of the number of men authorized by law, and their requirements as shown by years of experience, and also with the purpose on the part of the bureau officers to provide for all contingencies that may arise during the time for which the estimates are made. Exclusive of engineer estimates (presented in accordance with acts of Congress calling for surveys and estimates for improvements at various localities), the estimates now presented are about six millions in excess of the appropriations for the years 1874-75 and 1875-76. This increase is asked in order to provide for the increased cavalry force (should their services be necessary), to prosecute economically work upon important public buildings, to provide for armament of fortifications and manufacture of small arms, and to replenish the working stock in the supply departments. The appropriations for these last named have for the past few years been so limited that the accumulations in store will be entirely exhausted during the present year, and it will be necessary to at once begin to replenish them.

I invite your special attention to the following recommendations of the Secretary of War:

First. That the claims under the act of July 4, 1864, for supplies taken by the Army during the war be removed from the offices of the Quartermaster and Commissary Generals and transferred to the Southern Claims Commission. These claims are of precisely similar nature to those now before the Southern Claims Commission, and the War Department bureaus have not the clerical force for their examination nor proper machinery for investigating the loyalty of the claimants.

Second. That Congress sanction the scheme of an annuity fund for the benefit of the families of deceased officers, and that it also provide for the permanent organization of the Signal Service, both of which were recommended in my last annual message.

Third. That the manufacturing operations of the Ordnance Department be concentrated at three arsenals and an armory, and that the remaining arsenals be sold and the proceeds applied to this object by the Ordnance Department.

The appropriations for river and harbor improvements for the current year were $5,015,000. With my approval, the Secretary of War directed that of this amount $2,000,000 should be expended, and no new works should be begun and none prosecuted which were not of national importance. Subsequently this amount was increased to $2,237,600, and the works are now progressing on this basis.

The improvement of the South Pass of the Mississippi River, under James B. Eads and his associates, is progressing favorably. At the present time there is a channel of 20.3 feet in depth between the jetties at the mouth of the pass and 18.5 feet at the head of the pass. Neither channel, however, has the width required before payments can be made by the United States. A commission of engineer officers is now examining these works, and their reports will be presented as soon as received.

The report of the Secretary of the Navy shows that branch of the service to be in condition as effective as it is possible to keep it with the means and authority given the Department. It is, of course, not possible to rival the costly and progressive establishments of great European powers with the old material of our Navy, to which no increase has been authorized since the war, except the eight small cruisers built to supply the place of others which had gone to decay. Yet the most has been done that was possible with the means at command; and by substantially rebuilding some of our old ships with durable material and completely repairing and refitting our monitor fleet the Navy has been gradually so brought up that, though it does not maintain its relative position among the progressive navies of the world, it is now in a condition more powerful and effective than it ever has been in time of peace.

The complete repairs of our five heavy ironclads are only delayed on account of the inadequacy of the appropriations made last year for the working bureaus of the Department, which were actually less in amount than those made before the war, notwithstanding the greatly enhanced price of labor and materials and the increase in the cost of the naval service growing out of the universal use and great expense of steam machinery. The money necessary for these repairs should be provided at once, that they may be completed without further unnecessary delay and expense.

When this is done, all the strength that there is in our Navy will be developed and useful to its full capacity, and it will be powerful for purposes of defense, and also for offensive action, should the necessity for that arise within a reasonable distance from our shores.

The fact that our Navy is not more modern and powerful than it is has been made a cause of complaint against the Secretary of the Navy by persons who at the same time criticise and complain of his endeavors to bring the Navy that we have to its best and most efficient condition; but the good sense of the country will understand that it is really due to his practical action that we have at this time any effective naval force at command.

The report of the Postmaster-General shows the excess of expenditures (excluding expenditures on account of previous years) over receipts for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1876, to be $4,151,988.66.

Estimated expenditures for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1878, are $36,723,432.43.

Estimated revenue for same period is $30,645,165, leaving estimated excess of expenditure, to be appropriated as a deficiency, of $6,078,267.43.

The Postmaster-General, like his predecessor, is convinced that a change in the basis of adjusting the salaries of postmasters of the fourth class is necessary for the good of the service as well as for the interests of the Government, and urgently recommends that the compensation of the class of postmasters above mentioned be based upon the business of their respective offices, as ascertained from the sworn returns to the Auditor of stamps canceled.

A few postmasters in the Southern States have expressed great apprehension of their personal safety on account of their connection with the postal service, and have specially requested that their reports of apprehended danger should not be made public lest it should result in the loss of their lives. But no positive testimony of interference has been submitted, except in the case of a mail messenger at Spartanburg, in South Carolina, who reported that he had been violently driven away while in charge of the mails on account of his political affiliations. An assistant superintendent of the Railway Mail Service investigated this case and reported that the messenger had disappeared from his post, leaving his work to be performed by a substitute. The Postmaster-General thinks this case is sufficiently suggestive to justify him in recommending that a more severe punishment should be provided for the offense of assaulting any person in charge of the mails or of retarding or otherwise obstructing them by threats of personal injury.

"A very gratifying result is presented in the fact that the deficiency of this Department during the last fiscal year was reduced to $4,081,790.18, as against $6,169,938.88 of the preceding year. The difference can be traced to the large increase in its ordinary receipts (which greatly exceed the estimates therefor) and a slight decrease in its expenditures."

The ordinary receipts of the Post-Office Department for the past seven fiscal years have increased at an average of over 8 per cent per annum, while the increase of expenditures for the same period has been but about 5.50 per cent per annum, and the decrease of deficiency in the revenues has been at the rate of nearly 2 per cent per annum.

The report of the Commissioner of Agriculture accompanying this message will be found one of great interest, marking, as it does, the great progress of the last century in the variety of products of the soil; increased knowledge and skill in the labor of producing, saving, and manipulating the same to prepare them for the use of man; in the improvements in machinery to aid the agriculturist in his labors, and in a knowledge of those scientific subjects necessary to a thorough system of economy in agricultural production, namely, chemistry, botany, entomology, etc. A study of this report by those interested in agriculture and deriving their support from it will find it of value in pointing out those articles which are raised in greater quantity than the needs of the world require, and must sell, therefore, for less than the cost of production, and those which command a profit over cost of production because there is not an overproduction.

I call special attention to the need of the Department for a new gallery for the reception of the exhibits returned from the Centennial Exhibition, including the exhibits donated by very many foreign nations, and to the recommendations of the Commissioner of Agriculture generally.

The reports of the District Commissioners and the board of health are just received—too late to read them and to make recommendations thereon—and are herewith submitted.

The international exhibition held in Philadelphia this year, in commemoration of the one hundredth anniversary of American independence, has proven a great success, and will, no doubt, be of enduring advantage to the country. It has shown the great progress in the arts, sciences, and mechanical skill made in a single century, and demonstrated that we are but little behind older nations in any one branch, while in some we scarcely have a rival. It has served, too, not only to bring peoples and products of skill and labor from all parts of the world together, but in bringing together people from all sections of our own country, which must prove a great benefit in the information imparted and pride of country engendered.

It has been suggested by scientists interested in and connected with the Smithsonian Institution, in a communication herewith, that the Government exhibit be removed to the capital and a suitable building be erected or purchased for its accommodation as a permanent exhibit. I earnestly recommend this; and believing that Congress would second this view, I directed that all Government exhibits at the Centennial Exhibition should remain where they are, except such as might be injured by remaining in a building not intended as a protection in inclement weather, or such as may be wanted by the Department furnishing them, until the question of permanent exhibition is acted on.

Although the moneys appropriated by Congress to enable the participation of the several Executive Departments in the International Exhibition of 1876 were not sufficient to carry out the undertaking to the full extent at first contemplated, it gives me pleasure to refer to the very efficient and creditable manner in which the board appointed from these several Departments to provide an exhibition on the part of the Government have discharged their duties with the funds placed at their command. Without a precedent to guide them in the preparation of such a display, the success of their labors was amply attested by the sustained attention which the contents of the Government building attracted during the period of the exhibition from both foreign and native visitors.

I am strongly impressed with the value of the collection made by the Government for the purposes of the exhibition, illustrating, as it does, the mineral resources of the country, the statistical and practical evidences of our growth as a nation, and the uses of the mechanical arts and the applications of applied science in the administration of the affairs of Government.

Many nations have voluntarily contributed their exhibits to the United States to increase the interest in any permanent exhibition Congress may provide for. For this act of generosity they should receive the thanks of the people, and I respectfully suggest that a resolution of Congress to that effect be adopted.

The attention of Congress can not be too earnestly called to the necessity of throwing some greater safeguard over the method of choosing and declaring the election of a President. Under the present system there seems to be no provided remedy for contesting the election in any one State. The remedy is partially, no doubt, in the enlightenment of electors. The compulsory support of the free school and the disfranchisement of all who can not read and write the English language, after a fixed probation, would meet my hearty approval. I would not make this apply, however, to those already voters, but I would to all becoming so after the expiration of the probation fixed upon. Foreigners coming to this country to become citizens, who are educated in their own language, should acquire the requisite knowledge of ours during the necessary residence to obtain naturalization. If they did not take interest enough in our language to acquire sufficient knowledge of it to enable them to study the institutions and laws of the country intelligently, I would not confer upon them the right to make such laws nor to select those who do.

I append to this message, for convenient reference, a synopsis of administrative events and of all recommendations to Congress made by me during the last seven years. Time may show some of these recommendations not to have been wisely conceived, but I believe the larger part will do no discredit to the Administration. One of these recommendations met with the united opposition of one political party in the Senate and with a strong opposition from the other, namely, the treaty for the annexation of Santo Domingo to the United States, to which I will specially refer, maintaining, as I do, that if my views had been concurred in the country would be in a more prosperous condition to-day, both politically and financially.

Santo Domingo is fertile, and upon its soil may be grown just those tropical products of which the United States use so much, and which are produced or prepared for market now by slave labor almost exclusively, namely, sugar, coffee, dyewoods, mahogany, tropical fruits, tobacco, etc. About 75 per cent of the exports of Cuba are consumed in the United States. A large percentage of the exports of Brazil also find the same market. These are paid for almost exclusively in coin, legislation, particularly in Cuba, being unfavorable to a mutual exchange of the products of each country. Flour shipped from the Mississippi River to Havana can pass by the very entrance to the city on its way to a port in Spain, there pay a duty fixed upon articles to be reexported, transferred to a Spanish vessel and brought back almost to the point of starting, paying a second duty, and still leave a profit over what would be received by direct shipment. All that is produced in Cuba could be produced in Santo Domingo. Being a part of the United States, commerce between the island and mainland would be free. There would be no export duties on her shipments nor import duties on those coming here. There would be no import duties upon the supplies, machinery, etc., going from the States. The effect that would have been produced upon Cuban commerce, with these advantages to a rival, is observable at a glance. The Cuban question would have been settled long ago in favor of "free Cuba." Hundreds of American vessels would now be advantageously used in transporting the valuable woods and other products of the soil of the island to a market and in carrying supplies and emigrants to it. The island is but sparsely settled, while it has an area sufficient for the profitable employment of several millions of people. The soil would have soon fallen into the hands of United States capitalists. The products are so valuable in commerce that emigration there would have been encouraged; the emancipated race of the South would have found there a congenial home, where their civil rights would not be disputed and where their labor would be so much sought after that the poorest among them could have found the means to go. Thus in cases of great oppression and cruelty, such as has been practiced upon them in many places within the last eleven years, whole communities would have sought refuge in Santo Domingo. I do not suppose the whole race would have gone, nor is it desirable that they should go. Their labor is desirable—indispensable almost—where they now are. But the possession of this territory would have left the negro "master of the situation," by enabling him to demand his rights at home on pain of finding them elsewhere.

I do not present these views now as a recommendation for a renewal of the subject of annexation, but I do refer to it to vindicate my previous action in regard to it.

With the present term of Congress my official life terminates. It is not probable that public affairs will ever again receive attention from me further than as a citizen of the Republic, always taking a deep interest in the honor, integrity, and prosperity of the whole land.

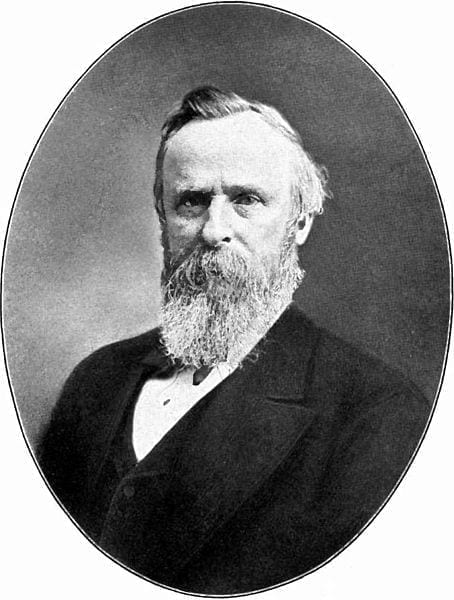

Inaugural Address (1877)

March 05, 1877

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.