Introduction

In early May 1866, the city of Memphis, TN, erupted in three days of racial fighting that left 48 citizens dead—46 blacks and two whites. Countless homes and schools, churches, and businesses burned in the uprising. In response, General Oliver O. Howard, commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, ordered an investigation into the causes of the riots. The Freedmen’s Bureau, established in March 1865 to help the formerly enslaved people in the South transition to freedom. The Bureau was concerned about the freedmen’s safety. It authorized “an investigation of the cause, origin, and results of the Memphis” violence.

Presented in a report written by Colonel Charles F. Johnson, Inspector General for the states of Kentucky and Tennessee, and Major T. W. Gilbreth, an aide-de-camp to General Howard,

the investigation concluded that such an intense “general feeling of hostility” existed in Memphis between whites and blacks that only the “slightest provocation” was necessary to spark a riot. One provocation occurred on April 30, when three black men and four Irish policeman engaged in a street fight. The next day, an estimated 50 blacks attempted to prevent a white officer from arresting a black ex-soldier. Shooting erupted, sparking the ensuing riots.

The situation in Memphis was volatile for months before the riots. The city’s free black population had quadrupled following the end of the Civil War in April 1865, creating pressure for jobs and housing. Many new black inhabitants were Civil War veterans living in South Memphis near Fort Pickering. They refused to accept second-class citizenship after contributing to the Confederacy’s defeat. Almost simultaneously, the city’s immigrant population was exploding, mostly from recent Irish immigrants, who also needed jobs and housing. Many of the Irish found employment as policemen and firemen, while blacks found jobs in manual labor. Blacks resented the Irish being in a position of authority, and the Irish cops exhibited racial bias toward blacks.

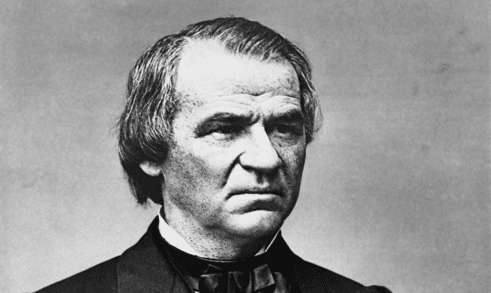

The report also considered national politics. The Memphis riots, as well as those in New Orleans twelve weeks later, occurred during a political battle over Reconstruction policy. Radical Republicans in Congress called for a more punitive approach to the former confederates. In contrast, President Andrew Johnson’s policy accepting ex-confederate control of reconstructed southern state governments suggested to many Americans that the president’s policies were failing. Radical Republicans argued that the riots called into question the Freedmen’s Bureau ability to protect black people in the South. They therefore wished to maintain and strengthen the federal military presence in the region.

Johnson and Gilbreth’s report to General Howard did not include specific policy recommendations or reforms. It highlighted the underlying racial tension in southern cities that foreshadowed how difficult winning the peace would become.

Source: Johnson, Charles F., and Gilbreth, T.W.. "Report of an investigation of the cause, origin, and results of the late riots in the city of Memphis, submitted May 22, 1866." From House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College. https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/45502.

Report of an investigation of the cause, origin, and results of the late riots in the city of Memphis made by Col. Charles F. Johnson, Inspector General States of Ky. And Tennessee and Major T. W. Gilbreth, A. D. C. To Maj. Genl. Howard, Commissioner Bureau R. F. & A. Lands.

The remote cause of the riot as it appears to us is a bitterness of feeling which has always existed between the low whites & blacks, both of whom have long advanced rival claims for superiority, both being as degraded as human beings can possibly be.

In addition to this general feeling of hostility there was an especial hatred among the city police for the Colored Soldiers, who were stationed here for a long time and had recently been discharged from the service of the U. S., which was most cordially reciprocated by the soldiers.

This has frequently resulted in minor affrays not considered worthy of notice by the authorities. These causes combined produced a state of feeling between whites and blacks, which would require only the slightest provocation to bring about an open rupture.

The Immediate Cause

On the evening of the 30th April 1866 several policemen (4) came down Causey Street, and meeting a number of Negroes forced them off the sidewalk. In doing so a Negro fell and a policeman stumbled over him. The police then drew their revolvers and attacked the Negroes, beating them with their pistols. Both parties then separated, deferring the settlement by mutual consent to some future time (see affidavit marked "A"). On the following day, May 1st, during the afternoon, between the hours of 3 and 5, a crowd of colored men, principally discharged soldiers, many of whom were more or less intoxicated, were assembled on South Street in South Memphis.

Three or four of these were very noisy and boisterous. Six policemen appeared on South Street, two of them arrested two of the Negroes and conducted them from the ground. The others remained behind to keep back the crowd, when the attempt was made by several Negroes to rescue their comrades. The police fell back when a promiscuous fight was indulged in by both parties.

During this affray one police officer was wounded in the finger, another (Stephens) was shot by the accidental discharge of his pistol in his own hand, and afterward died.

About this time the police fired upon unoffending Negroes remote from the riotous quarter. Colored soldiers with whom the police first had trouble had returned in the meantime to Fort Pickering. The police was soon reinforced and commenced firing on the colored people, men, women and children, in that locality, killing and wounding several.

Shortly after, the City Recorder (John C. Creighton) arrived upon the ground (corner of Causey and Vance Streets) and in a speech which received three hearty cheers from the crowd there assembled, councilled [sic] and urged the whites to arm and kill every Negro and drive the last one from the city. Then during this night the Negroes were hunted down by police, firemen and other white citizens, shot, assaulted, robbed, and in many instances their houses searched under the pretense of hunting for concealed arms, plundered, and then set on fire, during which no resistance so far as we can learn was offered by the Negroes.

A white man by the name of Dunn, a fireman, was shot and killed by another white man through mistake (reference is here made to accompanying affidavit mkd "B").

During the morning of the 2nd inst. (Wednesday) everything was perfectly quiet in the district of the disturbances of the previous day. A very few Negroes were in the streets, and none of them appeared with arms, or in any way excited except through fear. About 11 o’clock A. M. a posse of police and citizens again appeared in South Memphis and commenced an indiscriminate attack upon the Negroes, they were shot down without mercy, women suffered alike with the men, and in several instances little children were killed by these miscreants. During this day and night, with various intervals of quiet, the nuisance continued.

The city seemed to be under the control of a lawless mob during this and the two succeeding days (3rd & 4th). All crimes imaginable were committed from simple larceny to rape and murder. Several women and children were shot in bed. One woman (Rachel Johnson) was shot and then thrown into the flames of a burning house and consumed. Another was forced twice through the flames and finally escaped. In some instances houses were fired and armed men guarded them to prevent the escape of those inside. A number of men whose loyalty is undoubted, long residents of Memphis, who deprecated the riot during its progress, were denominated Yankees and Abolitionists, and were informed in language more emphatic than gentlemanly, that their presence here was unnecessary. To particularize further as to individual acts of inhumanity would extend the report to too great a length. But attention is respectfully called for further instances to affidavits accompanying marked C, E, F & G.

The riot lasted until and including the 4th of May but during all this time the disturbances were not continual as there were different times of greater or less length in each day, in which the city was perfectly quiet, attacks occurring generally after sunset each day.

The rioters ceased their violence either of their own accord or from want of material to work on, the Negroes having hid themselves, many fleeing into the country.

Conduct of the Civil Authorities

The Hon. John Park, Mayor of Memphis, seemed to have lost entire control of his subordinates and either through lack of inclination and sympathy with the mob, or on utter want of capacity, completely failed to suppress the riot and preserve the peace of the city. His friends offer in extenuation of his conduct, that he was in a state of intoxication during a part or most of the time and was therefore unable to perform the high and responsible functions of his office. Since the riot no official notice has been taken of the occurrence either by the Mayor or the Board of Aldermen, neither have the City Courts taken cognizance of the numerous crimes committed.

Although many of the perpetrators are known, no arrests have been made, nor is there now any indication on the part of the Civil Authorities that any are meditated by them.

It appears the Sheriff of this County (P. M. Minters) endeavored to oppose the mob on the evening of the 1st of May, but his good intentions were thwarted by a violent speech delivered by John C. Creighton, City Recorder, who urged and directed the arming of the whites and the wholesale slaughter of blacks.

This speech was delivered on the evening of the 1st of May to a large crowd of police and citizens on the corner of Vance and Causey streets, and to it can be attributed in a great measure the continuance of the disturbances. The following is the speech as extracted from the affidavits herewith forwarded marked "B" . . . "That everyone of the citizens should get arms, organize and go through the Negro districts," and that he "was in favor of killing every God damned nigger" . . . "We are not prepared now, but let us prepare and clean out every damned son of a bitch of a nigger out of town . . . "Boys, I want you to go ahead and kill every damned one of the nigger race and burn up the cradle."

The effect of such language delivered by a municipal office so high in authority, to a promiscuous and excited assemblage can be easily perceived. From that time they seemed to act as though vested with full authority to kill, burn and plunder at will. The conduct of a great number of the city police, who are generally composed of the lowest class of whites selected without reference to their qualifications for the position, was brutal in the extreme. Instead of protecting the rights of persons and property as is their duty, they were chiefly concerned as murderers, incendiaries and robbers. At times they even protected the rest of the mob in their acts of violence.

No public meeting has been held by the citizens, although three weeks have now elapsed since the riot, thus by their silence appearing to approve of the conduct of the mob. The only regrets that are expressed by the mass of the people are purely financial. There are, however, very many honorable exceptions, chiefly among men who have fought against the Government in the late rebellion, who deprecate in strong terms, both the Civil Authorities and the rioters.

Action of Bvt. Brig. Genl. Ben P. Runkle, Chief Supt., Bureau R. F. and A. L., Sub-District of Memphis

General Runkle was waited upon every hour in the day during the riot, by colored men who begged of him protection for themselves and families, and he, an officer of the Army detailed as Agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau was suffered the humiliation of acknowledging his utter inability to protect them in any respect. His personal appearance at the scenes of the riot had no affect on the mob, and he had no troops at his disposal.

He was obliged to put his Headquarters in a defensive state, and we believe it was only owing to the preparations made, that they were not burned down. Threats had been openly made that the Bureau office would be burned, and the General driven from the town. He, with his officers and a small squad of soldiers and some loyal citizens who volunteered were obliged to remain there during Thursday and Friday nights.

The origin and results of the riot may be summed up briefly as follows:

The remote cause was the feeling of bitterness which as always existed between the two classes. The minor affrays which occurred daily, especially between the police and colored persons.

The general tone of certain city papers which in articles that have appeared almost daily, have councilled [sic] the low whites to open hostilities with the blacks.

The immediate cause was the collision heretofore spoken of between a few policemen and Negroes on the evening of the 30th of April in which both parties may be equally culpable, followed on the evening of the 1st May by another collision of a more serious nature and subsequently by an indiscriminate attack upon inoffensive colored men and women.

Three Negro churches were burned, also eight (8) school houses, five (5) of which belonged to the United States Government, and about fifty (50) private dwellings, owned, occupied or inhabited by freedmen as homes, and in which they had all their personal property, scanty though it be, yet valuable to them and in many instances containing the hard earnings of months of labor.

Large sums of money were taken by police and others, the amounts varying five (5) to five hundred (500) dollars, the latter being quite frequent owing to the fact that many of the colored men had just been paid off and discharged from the Army.

No dwellings occupied by white men exclusively were destroyed and we have no evidence of any white men having been robbed.

From the present disturbed condition of the freedmen in the districts where the riot occurred it is impossible to determine the exact number of Negroes killed and wounded. The number already ascertained as killed is about (30) thirty; and the number wounded about fifty (50). Two white men were killed, viz., Stephens, a policemen and Dunn of the Fire Department.

The Surgeon who attended Stephens gives it as his professional opinion that the wound which resulted in his death was caused by the accidental discharge of a pistol in his hands (see affidavit marked "B"). Dunn was killed May 1st by a white man through mistake (see affidavit marked "B"). Two others (both Policemen) were wounded, one slightly in the finger, the other (Slattersly) seriously.

The losses sustained by the Government and Negroes as per affidavits received up to date amount to the sum of ninety eight thousand, three hundred and nineteen dollars and fifty five cents ($98,319.55). Subsequent investigations will in all probability increase the amount to one hundred and twenty thousand dollars ($120,00.00 [sic]).

(signed) Chas. F. Jackson [sic]

Col. And Insptr. Genl. Ky. & Tenn.

T. W. Gilbreth

Aide-de-Camp.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.