No related resources

Introduction

Red Cloud (1822–1909) was a Lakota chief. The Lakota were one of the divisions of the Sioux (the name “Sioux” apparently derives from the French understanding of a term other Indian tribes around the western Great Lakes used to describe the Sioux). In the early eighteenth century, as a result of fighting among the Indian groups, the Lakota moved westward from the western Great Lakes area (present-day Minnesota and Wisconsin) onto lands held by other Indians. As they encountered horses on the plains, the Lakota began to develop the buffalo-hunting culture that European settlers would encounter more than a hundred years later. By that time the Lakota had become a major power among the Indians on the northern plains.

As Americans traveled west to Oregon and California, and then to Montana, after the discovery of gold (1848 and 1862 respectively) conflicts between Americans and the Lakota increased. Red Cloud’s War was the name given to a series of raids and skirmishes that occurred between 1866 and 1868. (The war also included the destruction of a cavalry detachment of eighty-one troopers by Indians in 1866, a fight that involved Red Cloud.) The fighting effectively closed the Bozeman Trail, in what is now the northeastern corner of Wyoming, connecting the Oregon Trail with the gold-mining areas of Montana.

The war concluded with the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), which created a Sioux reservation in what is now western South Dakota and gave the Sioux some adjacent land, including some in the area of the Bozeman Trail. Red Cloud signed the treaty, as did chiefs from other Indian tribes. As so often in such cases, the treaty did not produce peace. The Sioux fought with the Crow, the Indians who had occupied land the Sioux now used for hunting, and with Americans who continued to move through and settle on their lands, particularly after gold was discovered in the Black Hills (1875), part of the reservation created by the Treaty of Fort Laramie. The U.S. government did not, in the opinion of the Indians, meet its treaty responsibilities, which included providing food and tools. When Red Cloud made his visit to Washington in 1870, such problems were already occurring, as the Grant administration tried to develop its new peace policy with the Indians. Red Cloud had asked for the visit to discuss the Fort Laramie Treaty and the movement of the Lakota to a reservation.

Source: Second Annual Report of the Board of Indian Commissioners to the Secretary of the Interior for Submission to the President for the Year 1870 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1871), 38–41, available at https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=kS8wAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA38. We do not know who wrote the report of Red Cloud’s visit.

The visit of Red Cloud, chief of the Oglalas, with seventeen head chiefs and three squaws, of the northwestern bands of Sioux, together with Spotted Tail and four other chiefs of the Brulé Sioux of the Missouri River, to Washington and the East.[1] . . .

Red Cloud and the other Sioux chiefs were today, June 4th, taken by General Parker to see the arsenal and navy yard.[2] The secretary of war[3] and the officers of the post received them at the arsenal and did their best, with the materials at their command, to impress their visitors with the powers of the “Great Father.”[4] The surprise that was expected to be exhibited by their guests was dissipated, however, when it was observed that the squaws promptly placed their hands over their ears some time before the cannons, which were to be fired for their especial astonishment, were discharged, proving that they knew all about that long ago. . . . [T]he officers and men seemed to think no trouble too great to make the interviews instructive and profitable to their guests; and when at the close Red Cloud respectfully declined Mrs. Dahlgren’s[5] hospitable invitation to a luncheon, and the whole delegation of chiefs and women stepped aside from the path on which they were departing to shake hands affectionately with her infant children, the impression made by them was very favorable. . . .

The grand council between the Indian delegations, the secretary of the interior,[6] and Commissioner Parker, was held at the Indian Office yesterday morning, June 8, 1870. Several gentlemen holding official positions under the government, having relations with Indian tribes, were present, including General Smith, Commissioners Brunot and Colyer, of the Peace Commission, and others.[7] The red men took their seats in the council about 11 o’clock, the conference lasting until 1 o’clock. They were arrayed in all the finery they possess, and were evidently much impressed with the importance of the occasion. . . .

Remarks of Secretary Cox:[8]

Red Cloud and his people have now been here several days; and we have had him go about and see the sights, that he might know more about our people and their power. They will now know that what the president does is not because he is afraid, but because he wants to do that which is right and good. When our people grow so fast as to travel upon the plains, we wanted to find a place where they could live and not be troubled. For that reason our great soldier, General Sherman, made the treaty to give the Indians the country where they now are, and take our people out of it, so they could be there alone.[9]

Lately some of our people wanted to go there to look for gold, but the president refused to let them go, saying he had given the country to the Sioux. They may be sure that the president will do what he said, and that they may live peacefully in that territory. We have asked Congress to give us plenty of money to continue feeding them, that their rations may be sure, and we expect them to do that, and therefore we can say that that part of their request will be granted. We will send them also the goods promised.

They asked for powder and lead. I want to tell them first what we think and feel on that subject. The whites who live on the frontiers are frightened. They say that Red Cloud and his people have murdered some of them. We want Red Cloud and his people to say to us here, before they go away, that they will not do so, but will keep at peace with all our people. When they have said that, and told the people so, we think it will be safe for them to have arms to hunt with. Lately some whites have been killed.

Red Cloud:

I have heard reports of this thing up above, before I left. There are no Sioux south of the Pacific Railroad.[10]

The secretary continued:

We will believe that what he says is so; but, while the people are frightened, we cannot give the Indians guns, but when we find they are at peace we will do so. We believe that by Red Cloud and the rest of his chiefs coming here, and learning all about the country, we can induce him to be at peace. We want them to know that we shall watch every chance to do them good instead of hurt, if they will remain steadily our friends. The people who move out into that country, many of them, never saw an Indian; they don’t know their language, and cannot talk to them—cannot tell one tribe from another—so that when an Indian kills a white man anywhere they charge all Indians with it. The Indians must, therefore, try to make all other Indians keep peace with us also. When we stop having complaints from the frontier, and the people tell us they are friends, then we can do all that we want to do. We know it is a great loss to them to be separated from the buffalo and the other game. That is why we give them rations. We know, too, that it is hard for grown-up men to learn other ways of getting food and clothing. We are trying, therefore, to take care of them, and to give them things in place of those they lose. We hope, when they have gone through the country, and seen what the whites get from the ground and other sources, that they will be glad to have their children learn to do the same. We believe the little children can learn these things when the grown men cannot. The whites are now so many that we must live [as] near neighbors to each other, and then the Indians could not help learning the ways of the whites. We want to be good neighbors, and we will help them to try and live in peace with those near them. By this I do not mean that the whites shall come on their reservation given the Indians by General Sherman, but I mean they are to live beside the railroad, so that we may know that our people do them no wrong, and that they get their goods; and we are going to send out Mr. Brunot this summer to see you. When he goes he will ask what is the best thing we can do for them—if anyone has done them wrong, and they can tell him what they want, and when he comes back we will try to do what he will say they need to have done. The great thing we want to say to them is, they must keep the peace, and then we will do what is right for them.

When the secretary had finished, Red Cloud arose, shook hands, and talked:

The Great Spirit has seen me naked; and my Great Father, I have fought against him. I offered my prayers to the Great Spirits, so I could come here safe. Look at me. I was raised on this land where the sun rises—now I come from where the sun sets. Whose voice was first sounded on this land? The voice of the red people, who had but bows and arrows. The Great Father says he is good and kind to us. I don’t think so. I am good to his white people. From the word sent me I have come all the way to his home. My face is red; yours is white. The Great Spirit has made you to read and write, but not me. I have not learned. I come here to tell my Great Father what I do not like in my country. You are all close to my Great Father, and are a great many chiefs. The men the Great Father sends to us have no sense—no heart. What has been done in my country I did not want, did not ask for it; white people going through my country. Father, have you, or any of your friends here, got children? Do you want to raise them? Look at me; I come here with all these young men. All of them have children and want to raise them. The white children have surrounded me and have left me nothing but an island. When we first had this land we were strong, now are melting like snow on the hillside, while you are grown like spring grass. Now I have come a long distance to my Great Father’s house—see if I have left any blood in his land when I go. When the white man comes in my country he leaves a trail of blood behind him. Tell the Great Father to move Fort Fetterman[11] away and we will have no more trouble. I have two mountains in that country—the Black Hills and the Big Horn Mountain. I want the Great Father to make no roads through them. I have told these things three times; now I have come here to tell them the fourth time.

I do not want my reservation on the Missouri; this is the fourth time I have said so. Here are some people from there now. Our children are dying off like sheep; the country does not suit them. I was born at the forks of the Platte,[12] and I was told that the land belonged to me from north, south, east, and west. The red man has come to the Great Father’s house. The Oglalas are the last who have come here; but I come to hear and listen to the words of the Great Father. They have promised me traders, but we have none. At the mouth of Horse Creek they had made a treaty in 1862, and the man who made the treaty is the only one who has told me truths.[13] When you send goods to me, they are stolen all along the road, so when they reached me they were only a handful. They hold a paper for me to sign, and that is all I got for my lands. I know the people you send out there are liars. Look at me. I am poor and naked. I do not want war with my government. The railroad is passing through my country now; I have received no pay for the land—not even a brass ring. I want you to tell all this to “my Great Father.” . . .

At the conclusion of Red Cloud’s remarks to the secretary, Commissioner Parker said to Red Cloud:

The secretary will go to the president now, and tell him what Red Cloud has said today; he will also make arrangements to fix a time when the president will see and talk with him; the president had told him (Commissioner Parker) last evening that he would talk with him very soon, and when the president was ready for him he would send him word, and he would then have a chance to see the president and report to him what he wanted.

Red Cloud then said:

I forgot one thing. You might grant my people the powder we ask; we are but a handful, and you a great and powerful nation; you make all the ammunition; all I ask is enough for my people to kill game. The Great Spirit has made all things that I have in my country wild; I have to hunt them up; it is not like you, who go out and find what you want. I have eyes; I see all you whites, what you are doing; raising stock, etc. I know that I will have to come to that in a few years myself; it is good. I have no more to say. . . .

- 1. Spotted Tail (c. 1823–1881) was a chief of the Brulé band of Lakota; Red Cloud was from the Oglala band.

- 2. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ely S. Parker (1828–1895), a Seneca Indian accompanied the chiefs to the Washington Naval Yard. See Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

- 3. William Belknap (1829–1890).

- 4. The president of the United States.

- 5. The wife of the admiral in charge of the Navy Yard.

- 6. Jacob Cox (1828–1900).

- 7. The Board of Indian Commissioners was established in 1869 as part of Grant’s peace policy toward the Indians. Its purpose was to report on the condition of the Indians, especially the fulfillment of U.S. government obligations to them. Felix R. Brunot (1820–1898) was president of the commission.

- 8. The conference took place through a translator.

- 9. William Tecumseh Sherman (1820–1891), a prominent commander in the Union Army during the Civil War, at its completion became commander of Army forces in the West (1865–1869). In this position, he commanded the troops that fought against the Lakota and other tribes in Red Cloud’s War, which ended with the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868).

- 10. That is, the transcontinental railroad. Red Cloud takes the secretary to be talking about an incident that occurred to the south of Sioux lands.

- 11. Fort Fetterman, built in 1867, was part of a system of forts built to protect the Bozeman Trail

- 12. In western Nebraska near the border with Colorado.

- 13. We have not identified this treaty.

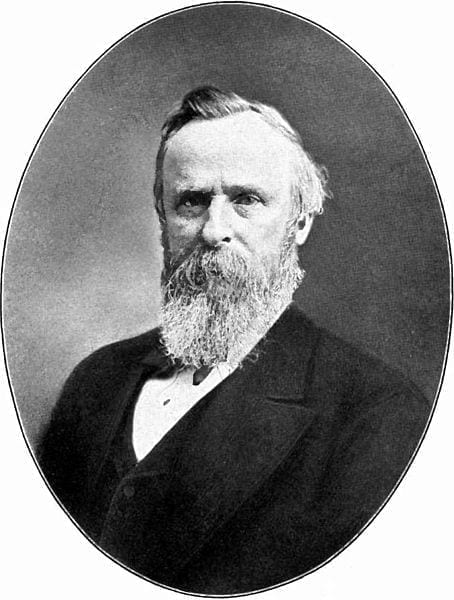

Annual Message to Congress (1870)

December 05, 1870

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.