Introduction

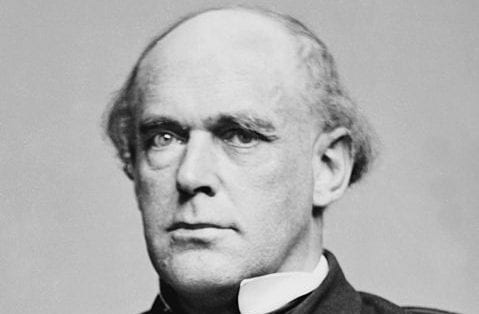

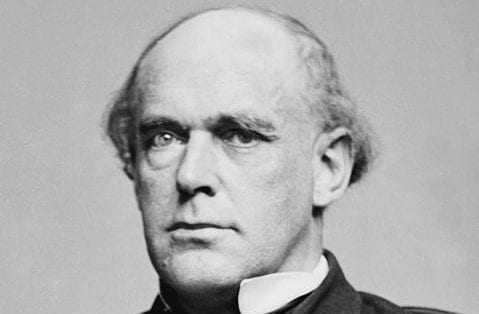

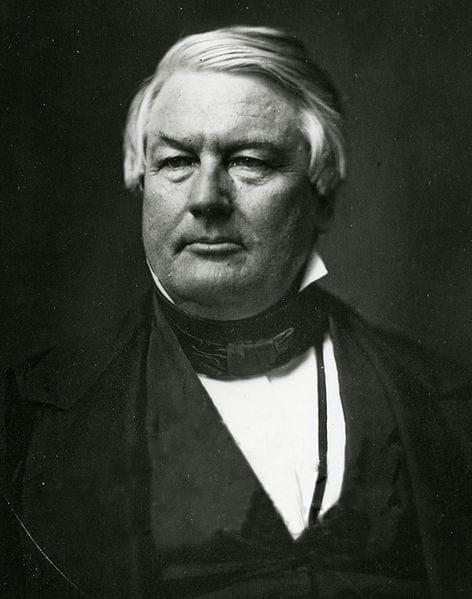

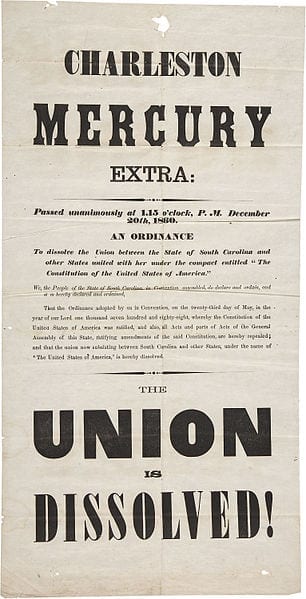

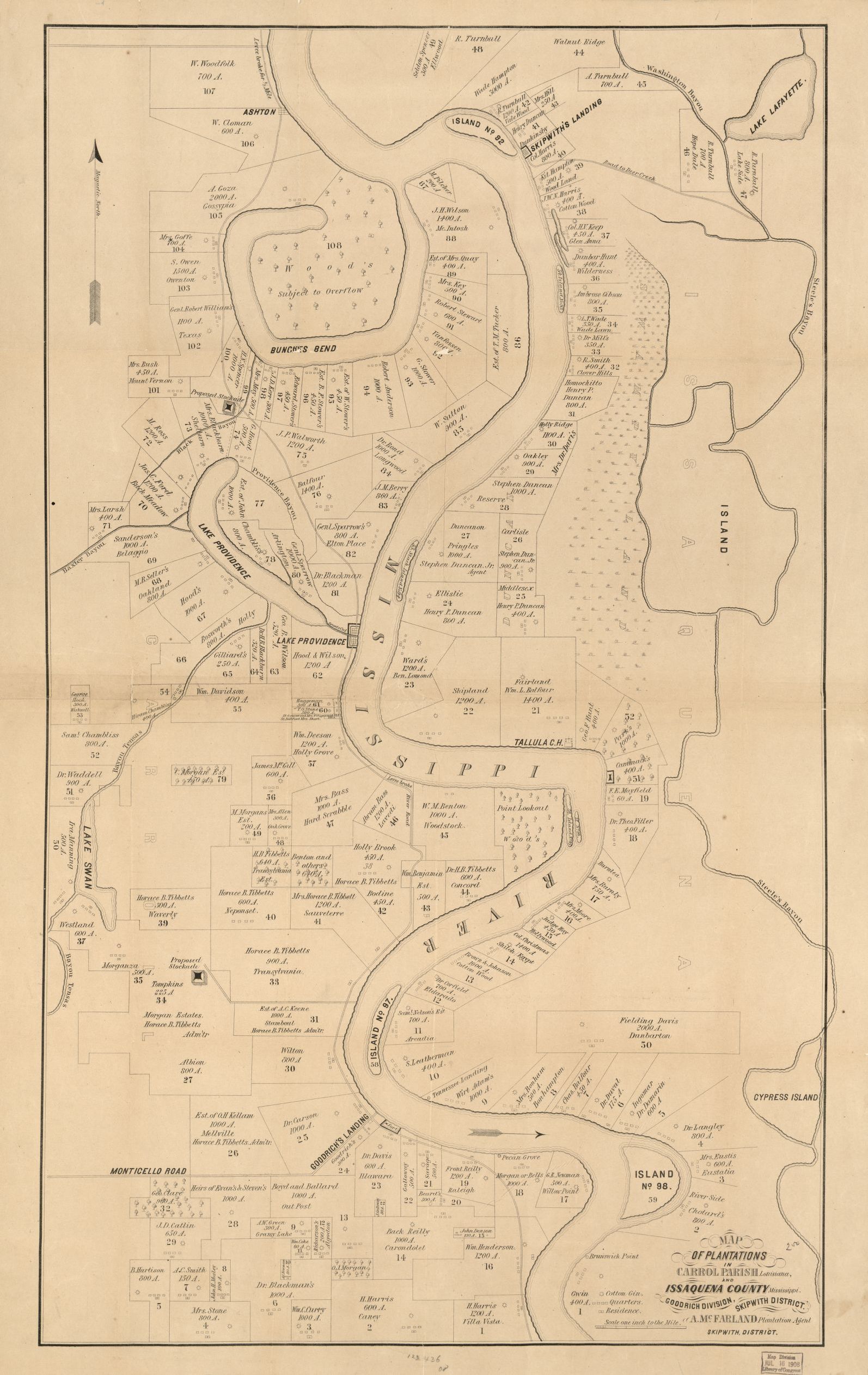

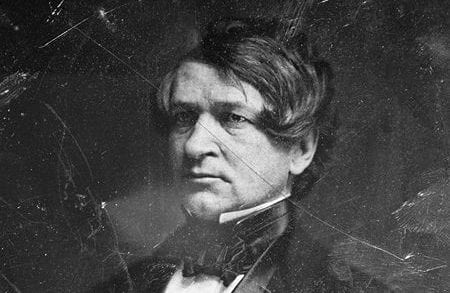

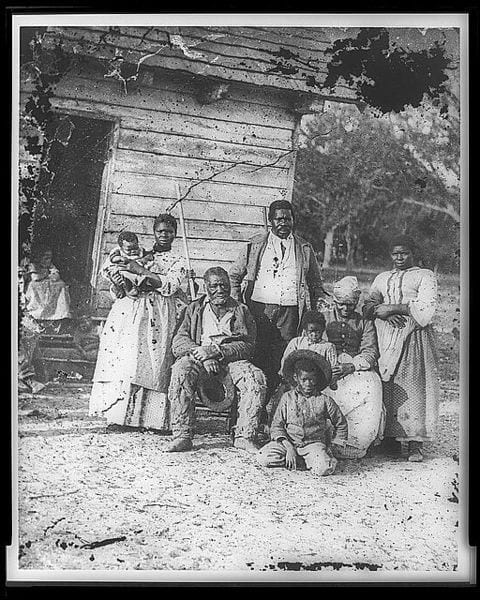

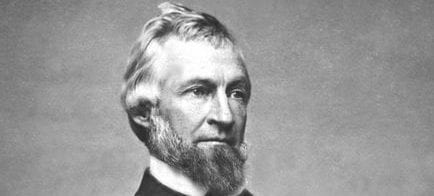

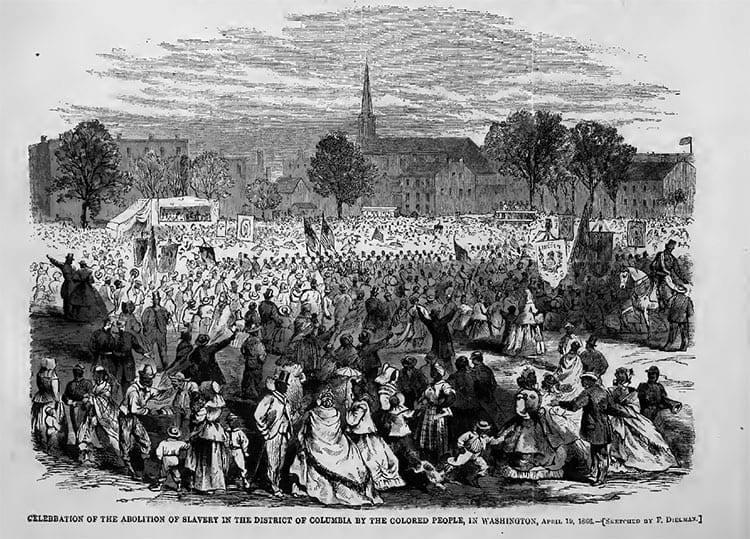

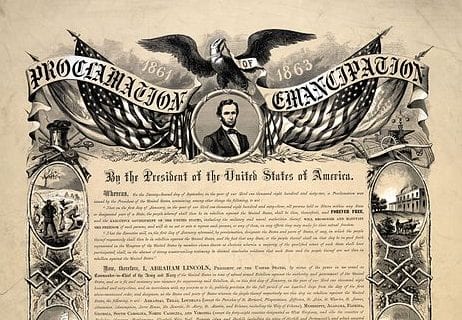

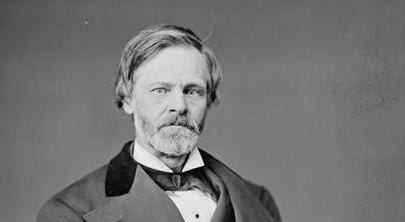

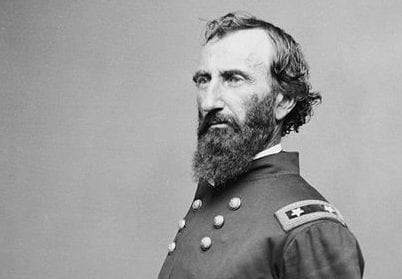

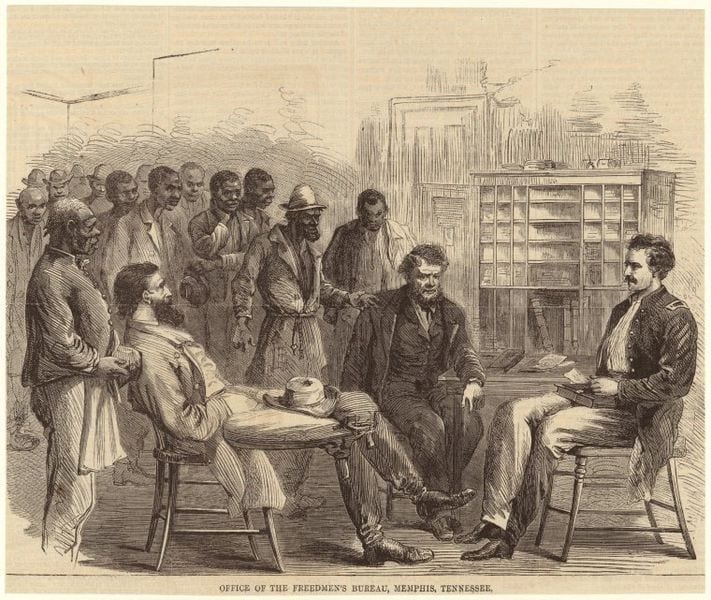

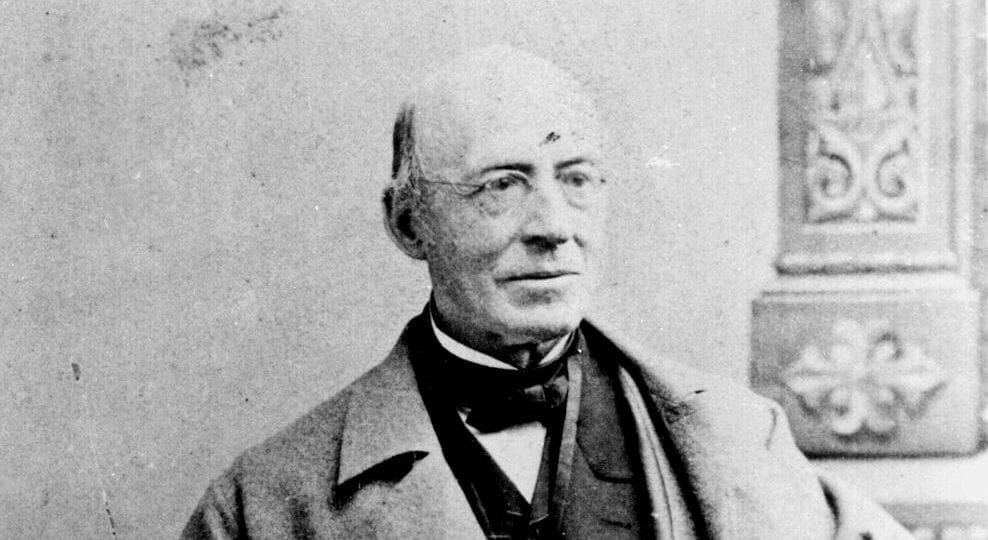

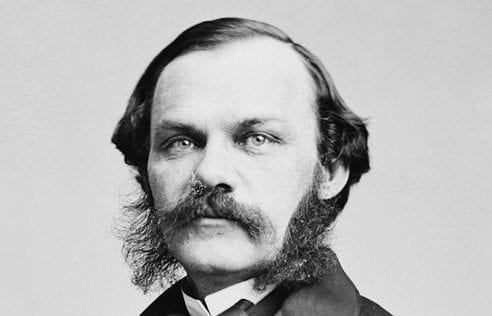

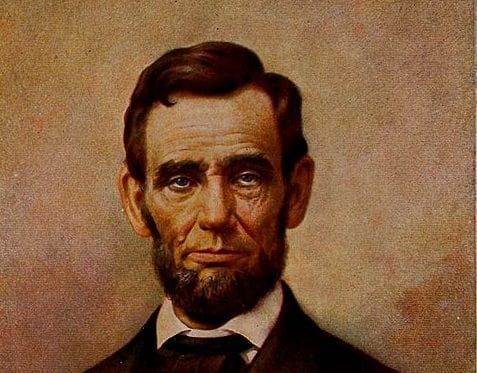

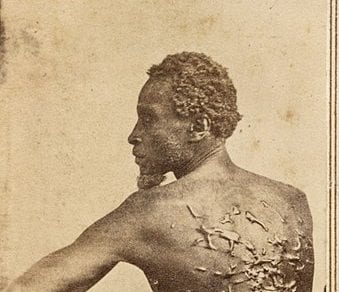

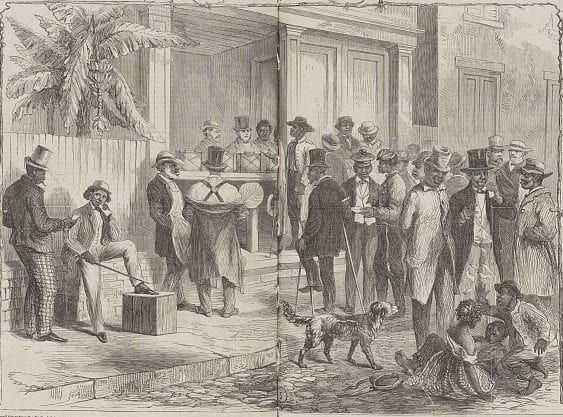

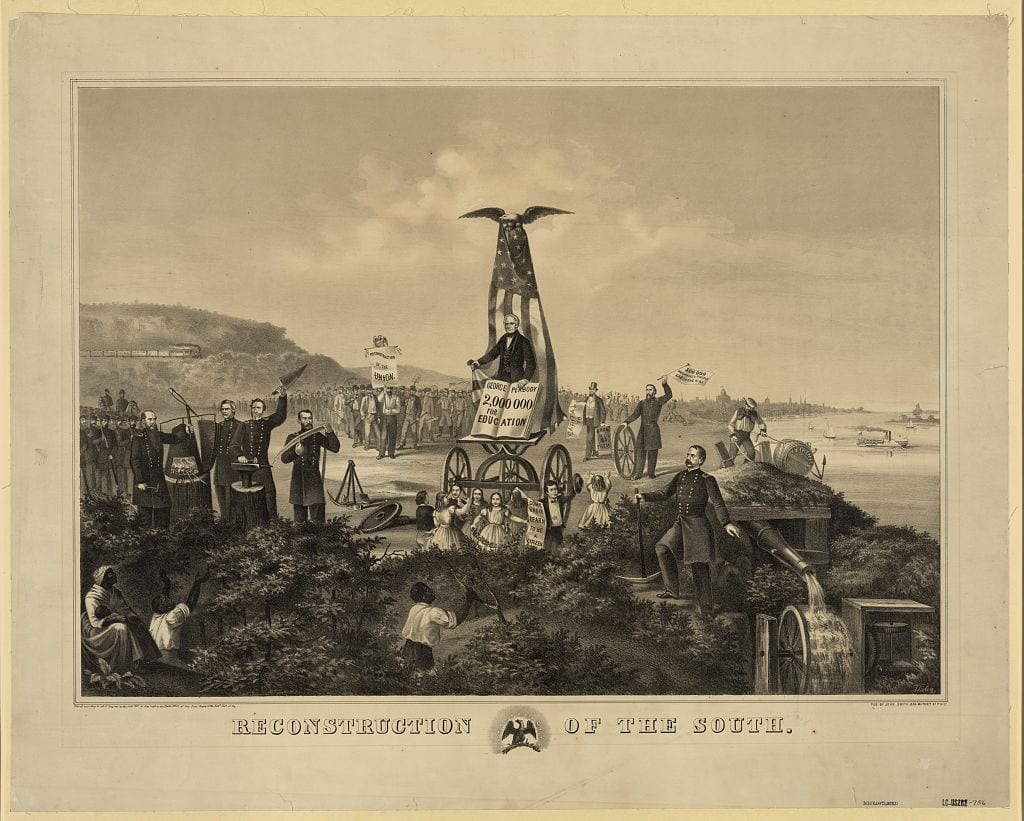

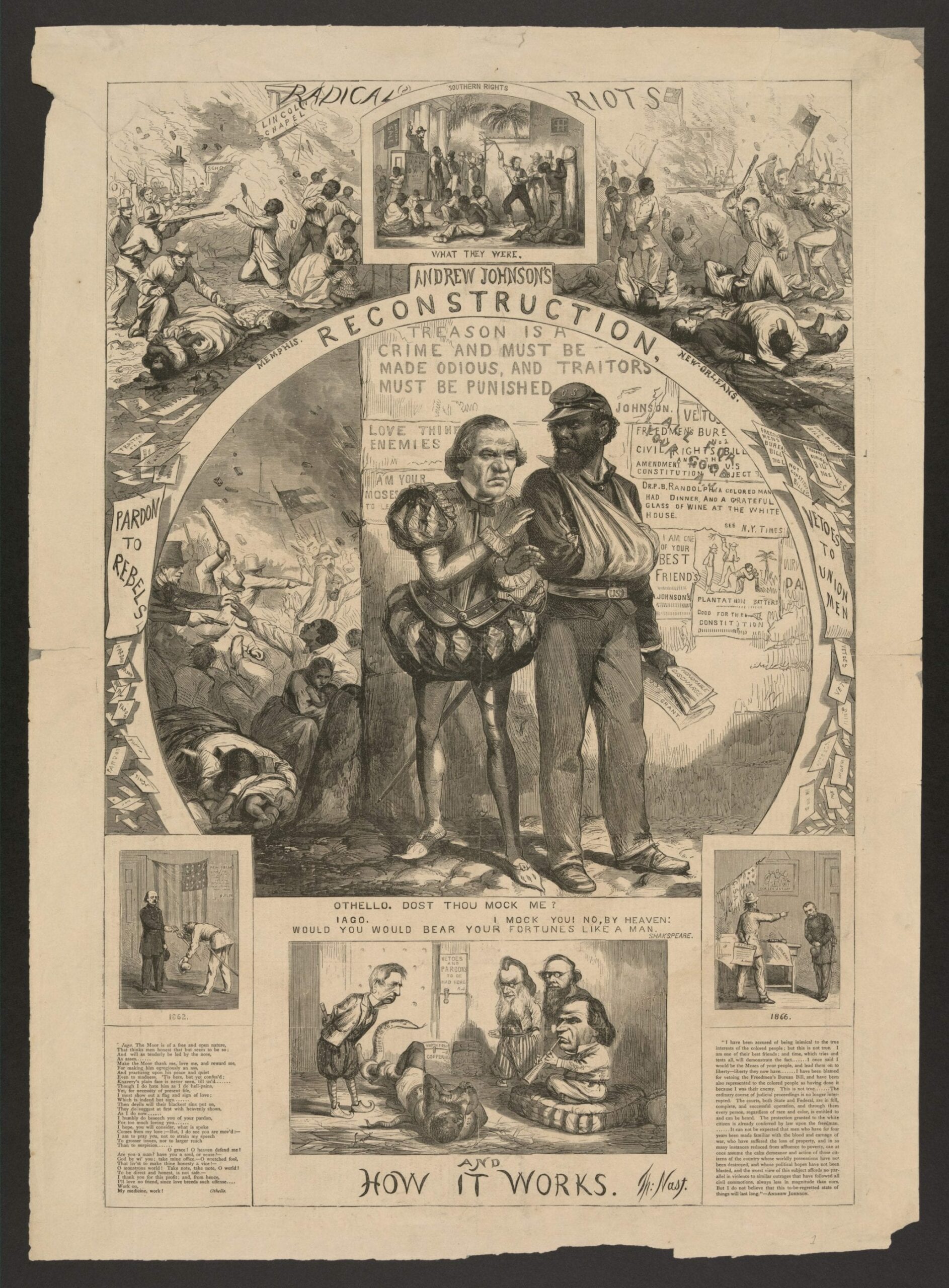

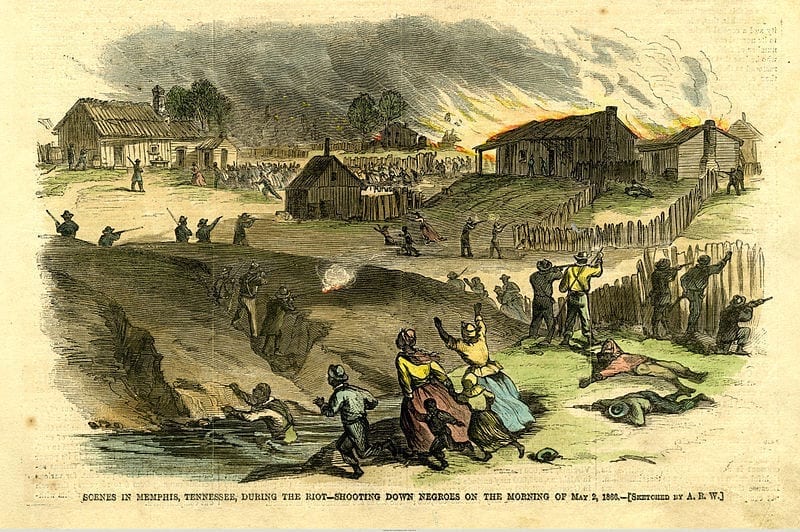

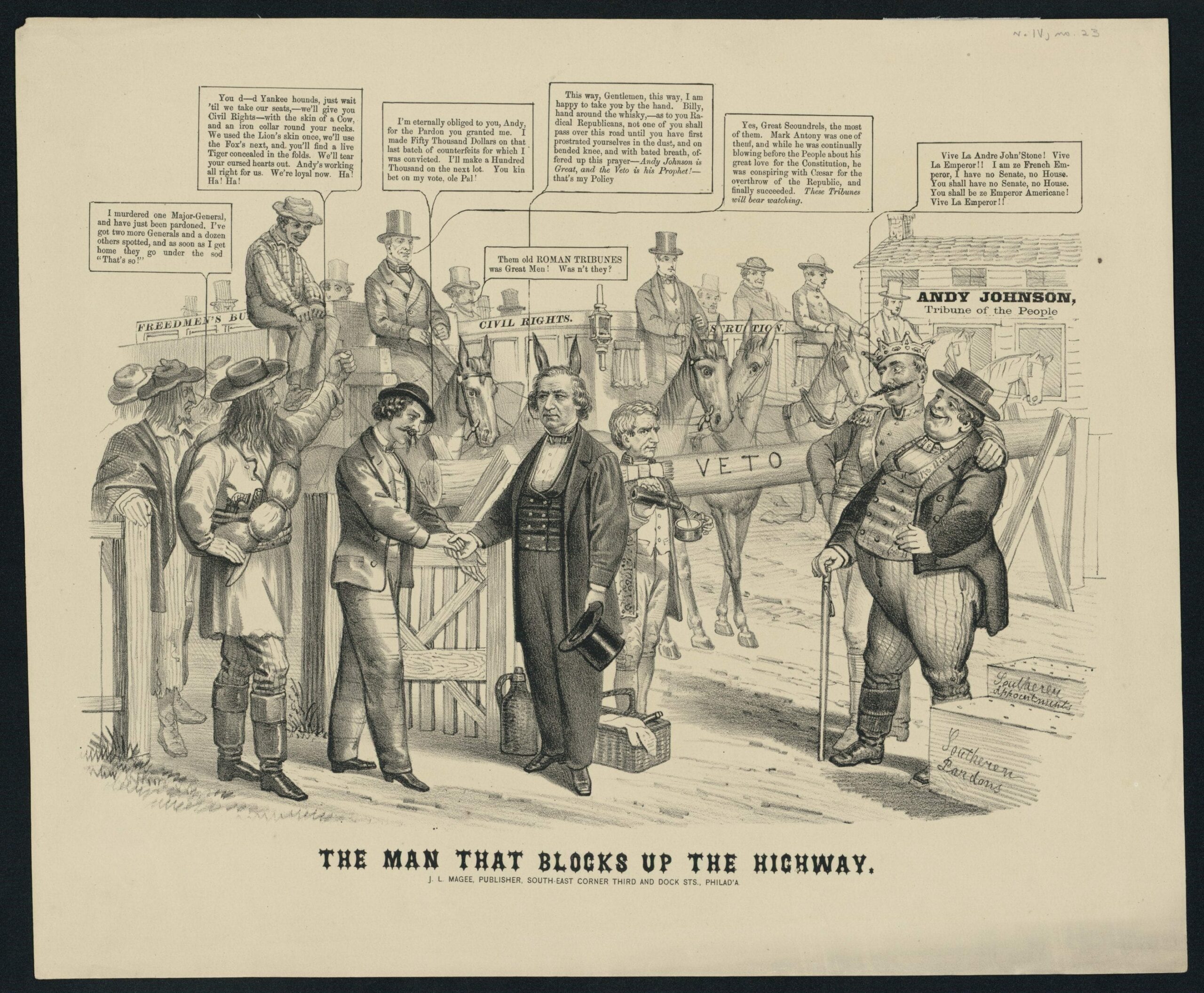

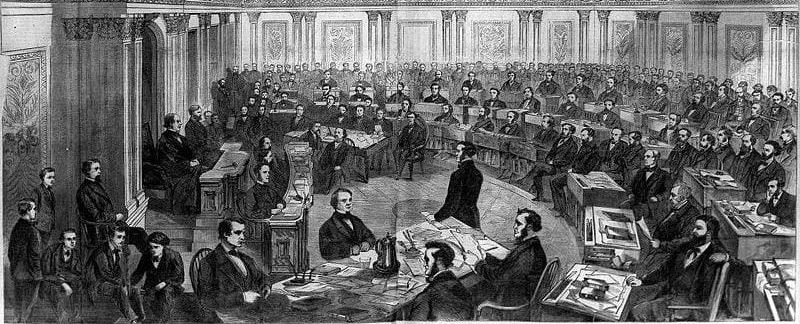

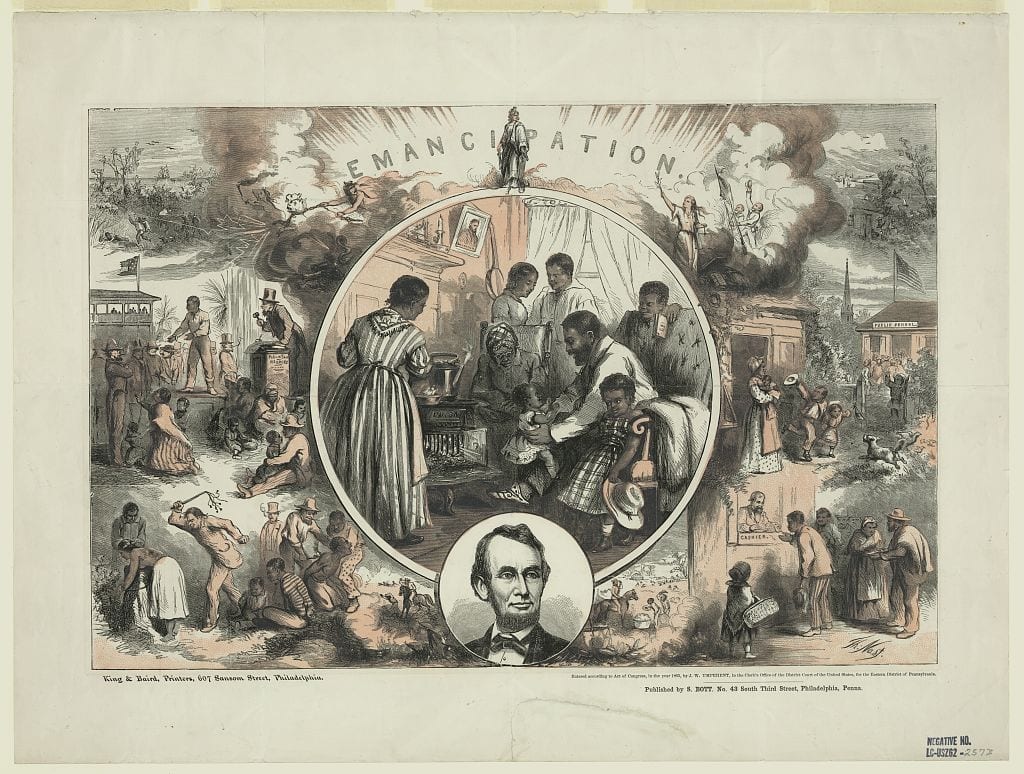

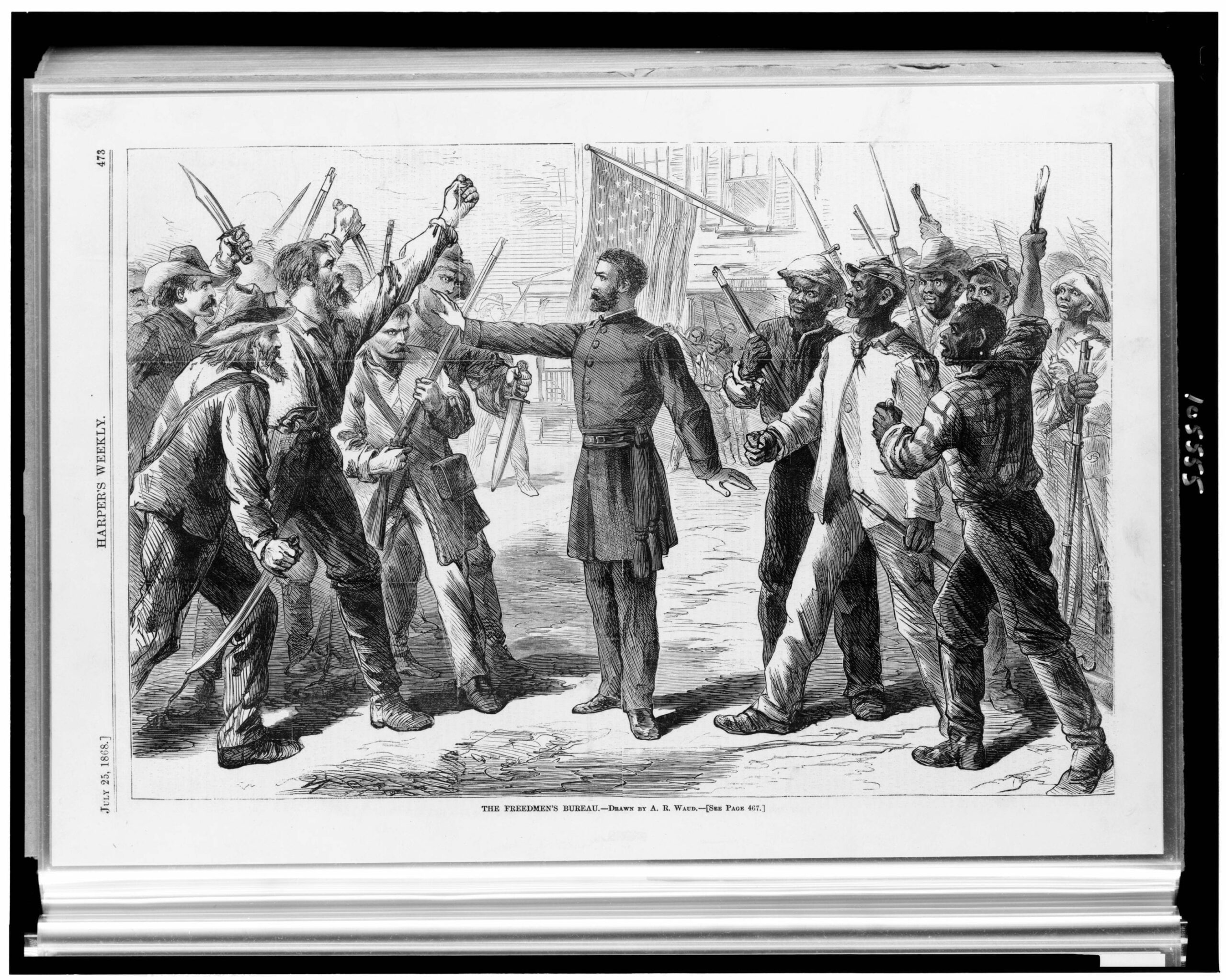

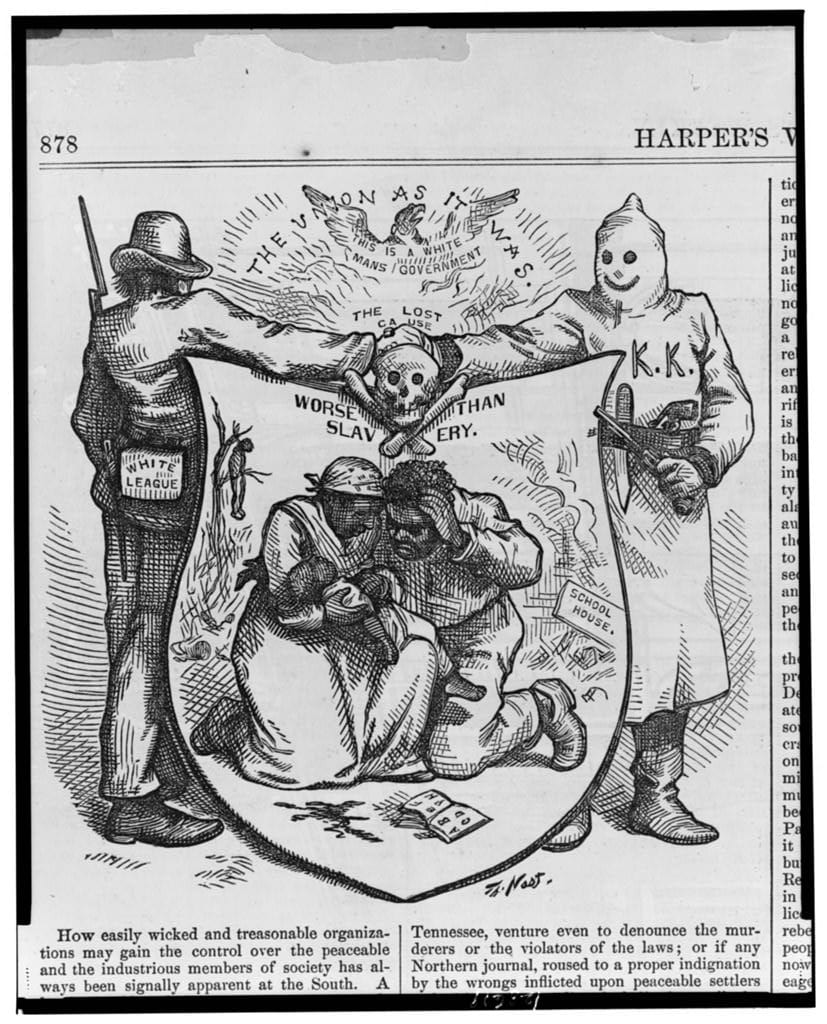

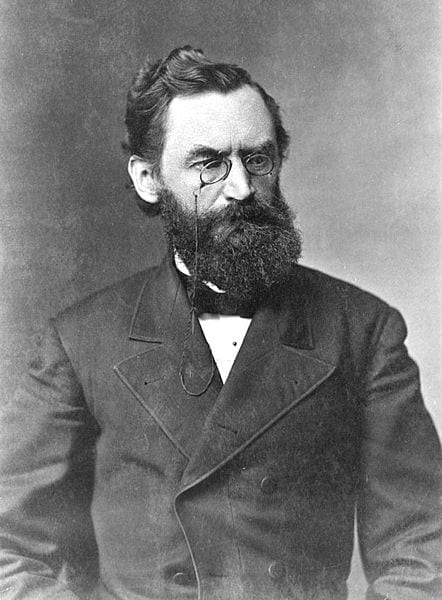

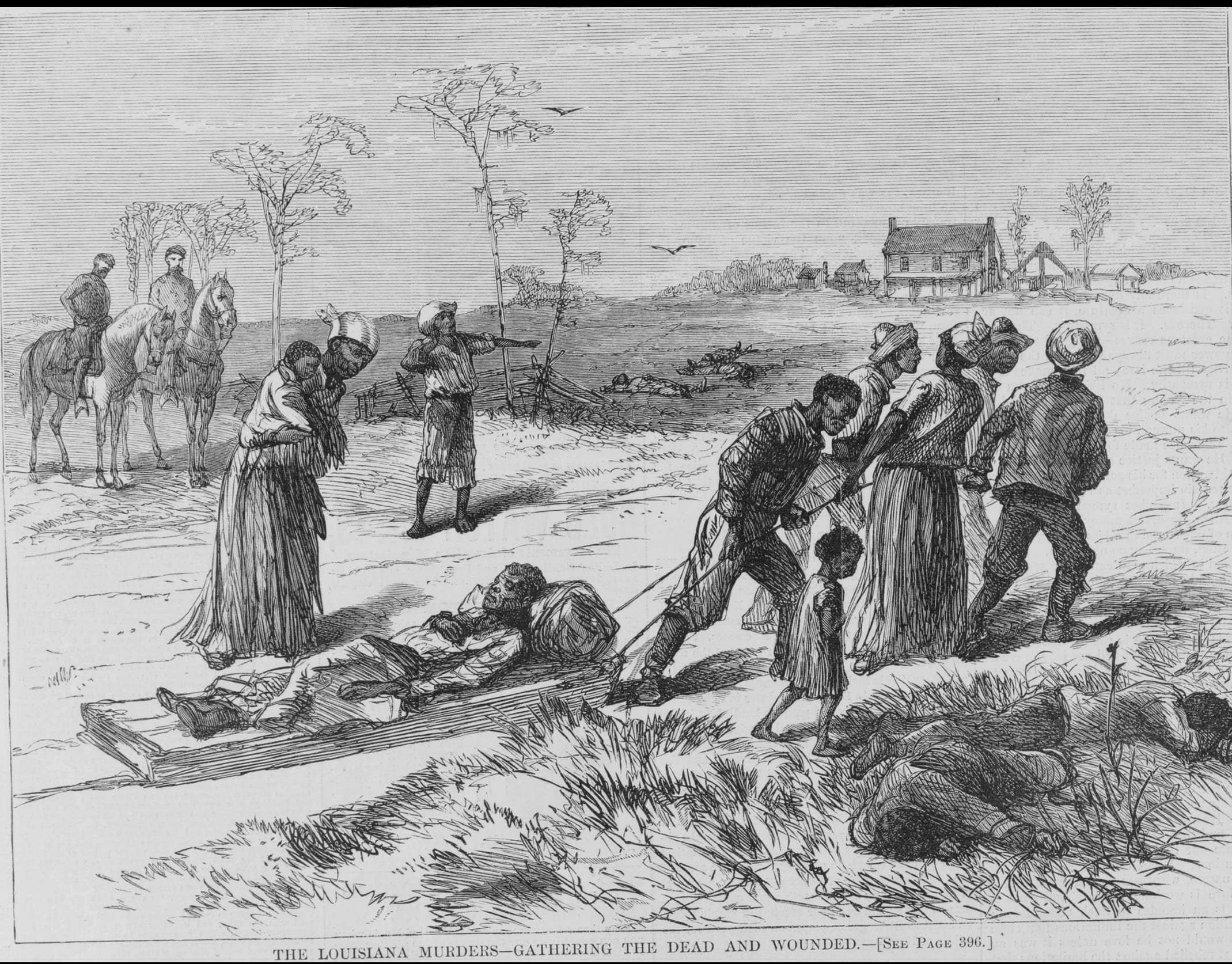

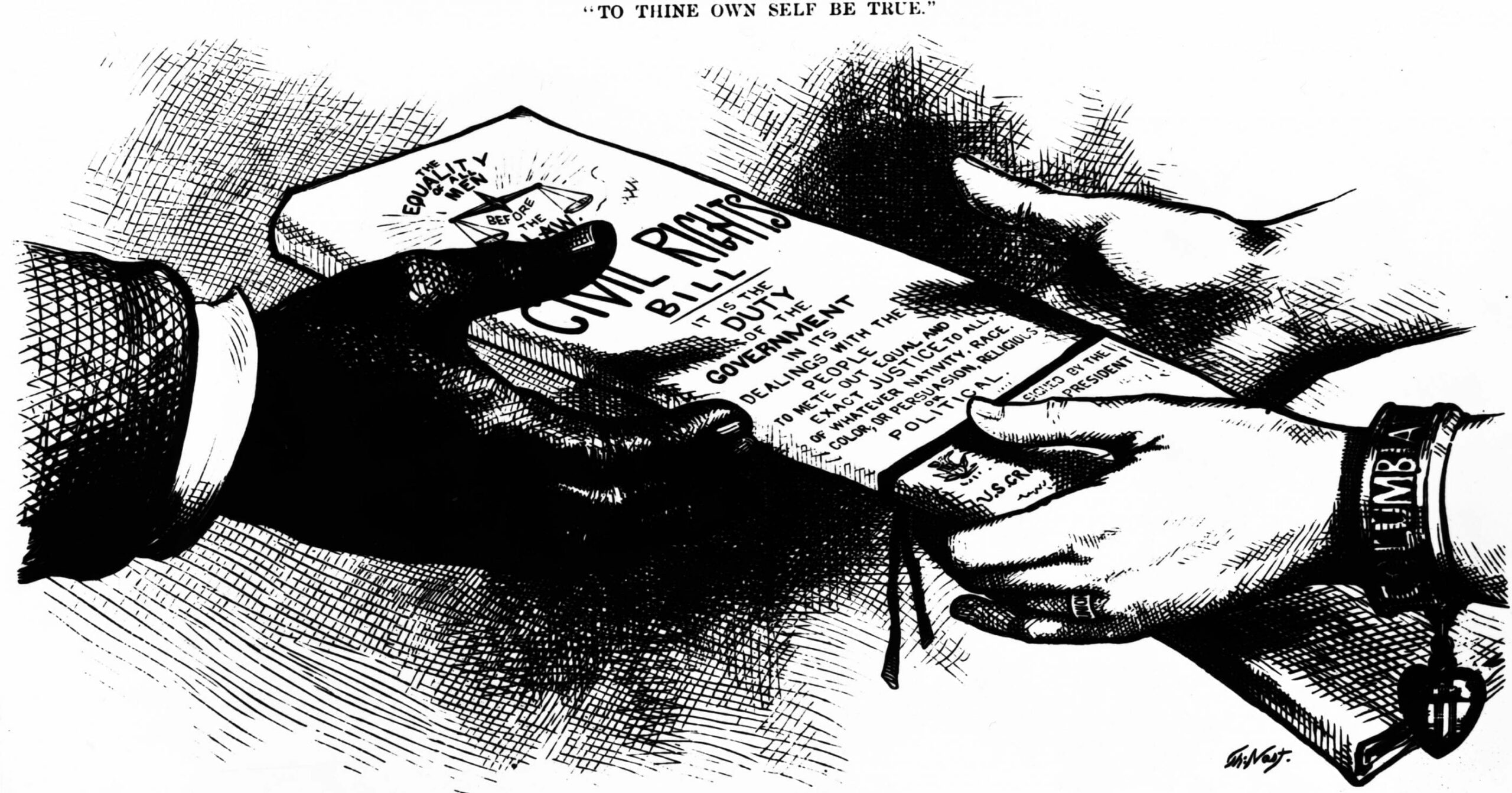

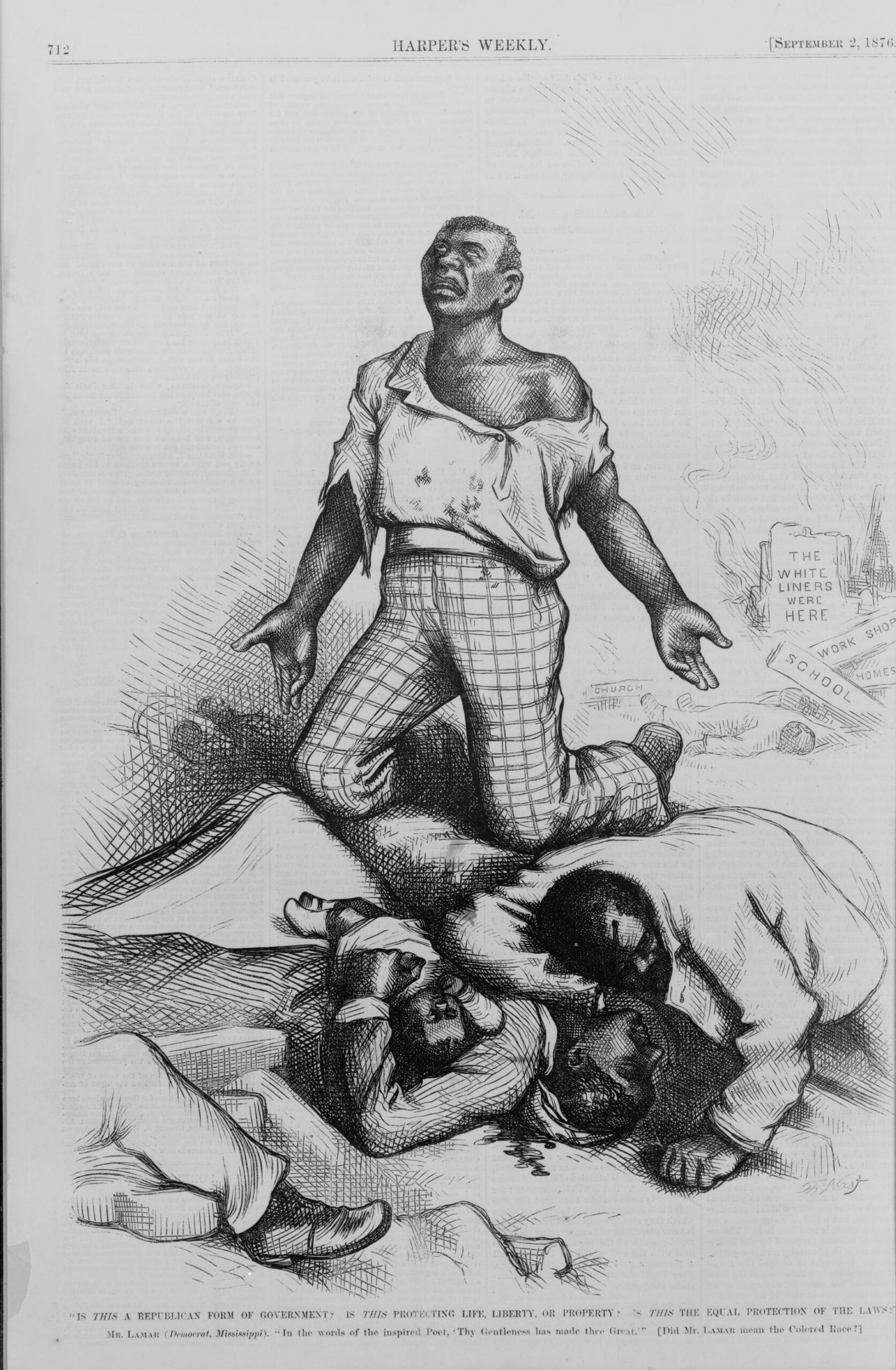

The United States arrested nine men for the murders at Colfax. Prosecution for the Colfax massacre became a test of national resolve to continue protecting civil rights in the reconstructed South under the Enforcement Acts. The Slaughterhouse Cases, which was decided just after the Colfax Massacre, offered a narrow reading of federal power under the new constitutional amendments. President Ulysses S. Grant’s Attorney General, Amos T. Akerman (1821-1880), had, prior to the Slaughterhouse Cases, been increasing the number of prosecutions throughout the South under the Enforcement Acts—from 879 in 1871 to 1,960 in 1873. Soon after the Slaughterhouse decision he became leery of using his authority. The extraordinary violence of the Colfax case, however, called for a federal response. Some conspirators were identified and legal proceedings began, with a heavy federal military presence to protect attorneys, judges, jury members and witnesses for the prosecution from mob violence. The federal prosecutor indicted William Cruikshank and his co-conspirators on more than a dozen charges of violating the rights of those killed at Colfax. The defendants appealed on the grounds that the federal prosecutor had no jurisdiction over this case since, according to the Slaughterhouse Cases, prosecuting such crimes was a state matter. The circuit court agreed with the defendants, but the federal prosecutor appealed the case to the United States Supreme Court. A 5 – 4 majority of the Supreme Court agreed that the 14th Amendment had not vested Congress with sufficient powers to conduct such prosecutions.

Source: United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1876). Available online from Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. https://goo.gl/JMfYBc.

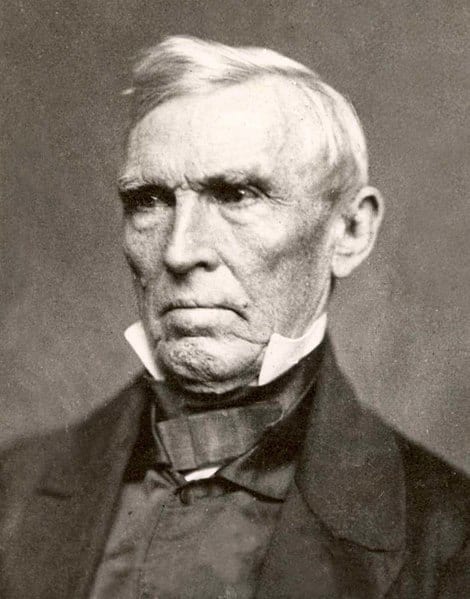

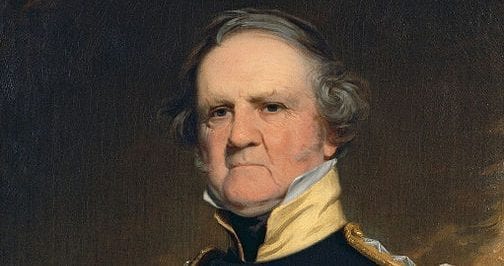

CHIEF JUSTICE WAITE delivered the opinion of the court.

. . .

We have in our political system a government of the United States and a government of each of the several States. Each one of these governments is distinct from the others, and each has citizens of its own who owe it allegiance, and whose rights, within its jurisdiction, it must protect. The same person may be at the same time a citizen of the United States and a citizen of a State, but his rights of citizenship under one of these governments will be different from those he has under the other. [Chief Justice Waite cited the Slaughterhouse cases as precedent for this opinion.] . . .

Experience made the fact known to the people of the United States that they required a national government for national purposes. The separate governments of the separate States, bound together by the Articles of Confederation alone, were not sufficient for the promotion of the general welfare of the people in respect to foreign nations, or for their complete protection as citizens of the confederated States. For this reason, the people of the United States, “in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty” to themselves and their posterity [preamble to the Constitution], ordained and established the government of the United States, and defined its powers by a constitution, which they adopted as its fundamental law, and made its rule of action.

The government thus established and defined is to some extent a government of the States in their political capacity. It is also, for certain purposes, a government of the people. Its powers are limited in number, but not in degree. Within the scope of its powers, as enumerated and defined, it is supreme and above the States; but beyond, it has no existence. . . .

The people of the United States resident within any State are subject to two governments: one State, and the other National; but there need be no conflict between the two. The powers which one possesses, the other does not. . . . True, it may sometimes happen that a person is amenable to both jurisdictions for one and the same act. Thus, if a marshal of the United States is unlawfully resisted while executing the process of the courts within a State, and the resistance is accompanied by an assault on the officer, the sovereignty of the United States is violated by the resistance, and that of the State by the breach of peace, in the assault. . . . This does not, however, imply that the two governments possess powers in common, or bring them into conflict with each other. It is the natural consequence of a citizenship which owes allegiance to two sovereignties, and claims protection from both. . . .

The government of the United States is one of delegated powers alone. Its authority is defined and limited by the Constitution. All powers not granted to it by that instrument are reserved to the States or the people. No rights can be acquired under the Constitution or laws of the United States, except such as the government of the United States has the authority to grant or secure. All that cannot be so granted or secured are left under the protection of the States.

We now proceed to an examination of the indictment, to ascertain whether the several rights, which it is alleged the defendants intended to interfere with, are such as had been in law and in fact granted or secured by the Constitution or laws of the United States.

The first and ninth counts state the intent of the defendants to have been to hinder and prevent the citizens named in the free exercise and enjoyment of their “lawful right and privilege to peaceably assemble together with each other and with other citizens of the United States for a peaceful and lawful purpose.” The right of the people peaceably to assemble for lawful purposes existed long before the adoption of the Constitution of the United States. . . . It was not, therefore, a right granted to the people by the Constitution. The government of the United States when established found it in existence, with the obligation on the part of the States to afford it protection. As no direct power over it was granted to Congress, it remains . . . subject to State jurisdiction. . . .

The first amendment to the Constitution prohibits Congress from abridging “the right of the people to assemble and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” This, like the other amendments proposed and adopted at the same time, was not intended to limit the powers of the State governments in respect to their own citizens, but to operate upon the National government alone . . . .

The particular amendment now under consideration assumes the existence of the right of the people to assemble for lawful purposes, and protects it against encroachment by Congress. The right was not created by the amendment; neither was its continuance guaranteed, except as against congressional interference. For their protection in its enjoyment . . . the people must look to the States. . . .

The second and tenth counts are equally defective. The right there specified is that of “bearing arms for a lawful purpose.” This is not a right granted by the Constitution. Neither is it in any manner dependent upon that instrument for its existence. The second amendment declares that it shall not be infringed; but this, as has been seen, means no more than that it shall not be infringed by Congress. . . .

The third and eleventh counts are even more objectionable. They charge the intent to have been to deprive the citizens named, they being in Louisiana, “of their respective several lives and liberty of person without due process of law.” This is nothing else than alleging a conspiracy to falsely imprison or murder citizens of the United States, being within the territorial jurisdiction of the State of Louisiana. The rights of life and personal liberty are natural rights of man. “To secure these rights,” says the Declaration of Independence, “governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The very highest duty of the States, when they entered into the Union under the Constitution, was to protect all persons within their boundaries in the enjoyment of these “unalienable rights with which they were endowed by their Creator.” Sovereignty, for this purpose, rests alone with the States. It is no more the duty or within the power of the United States to punish for a conspiracy to falsely imprison or murder within a State, than it would be to punish for false imprisonment or murder itself.

The fourteenth amendment prohibits a State from depriving any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; but this adds nothing to the rights of one citizen as against another. It simply furnishes an additional guaranty against any encroachment by the States upon the fundamental rights which belong to every citizen as a member of society. . . . These counts in the indictment do not call for the exercise of any of the powers conferred by this provision in the amendment.

The fourth and twelfth counts charge the intent to have been to prevent and hinder the citizens named, who were of African descent and persons of color, in “the free exercise and enjoyment of their several rights and privileges to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings . . . .” There is no allegation that this was done because of the race or color of the persons conspired against. When stripped of its verbiage, the case as presented amounts to nothing more than that the defendants conspired to prevent certain citizens of the United States, being within the State of Louisiana, from enjoying the equal protection of the laws of the State and of the United States.

The fourteenth amendment prohibits a State from denying to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws; but this provision does not, any more than the one which precedes it, and which we have just considered, add anything to the rights which one citizen has under the Constitution against another. The equality of the rights of citizens is a principle of republicanism. Every republican government is in duty bound to protect all its citizens in the enjoyment of this principle, if within its power. That duty was originally assumed by the States; and it still remains there. The only obligation resting upon the United States is to see that the States do not deny the right. . . .

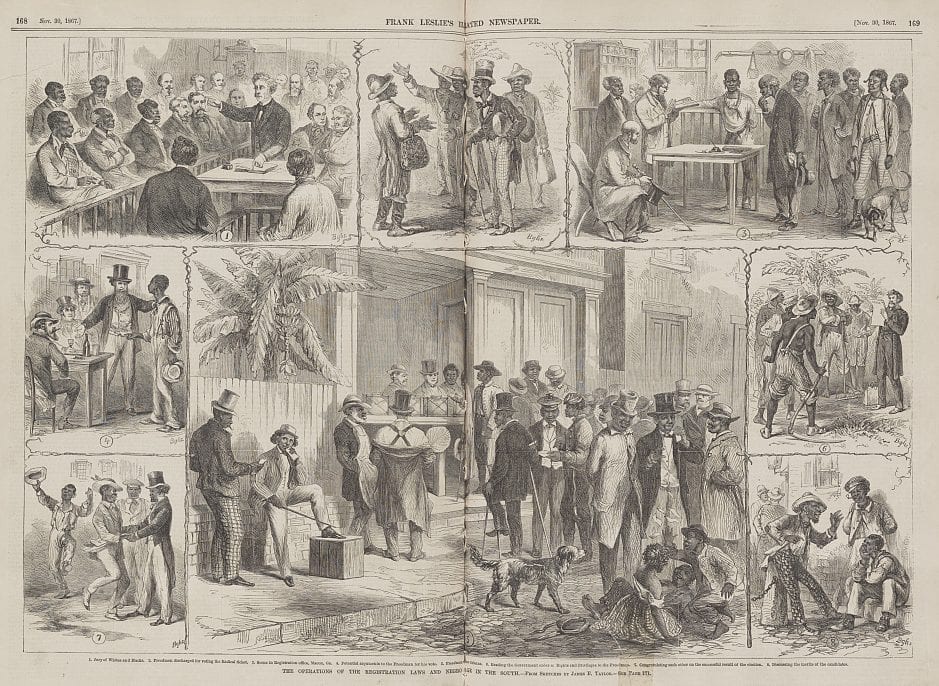

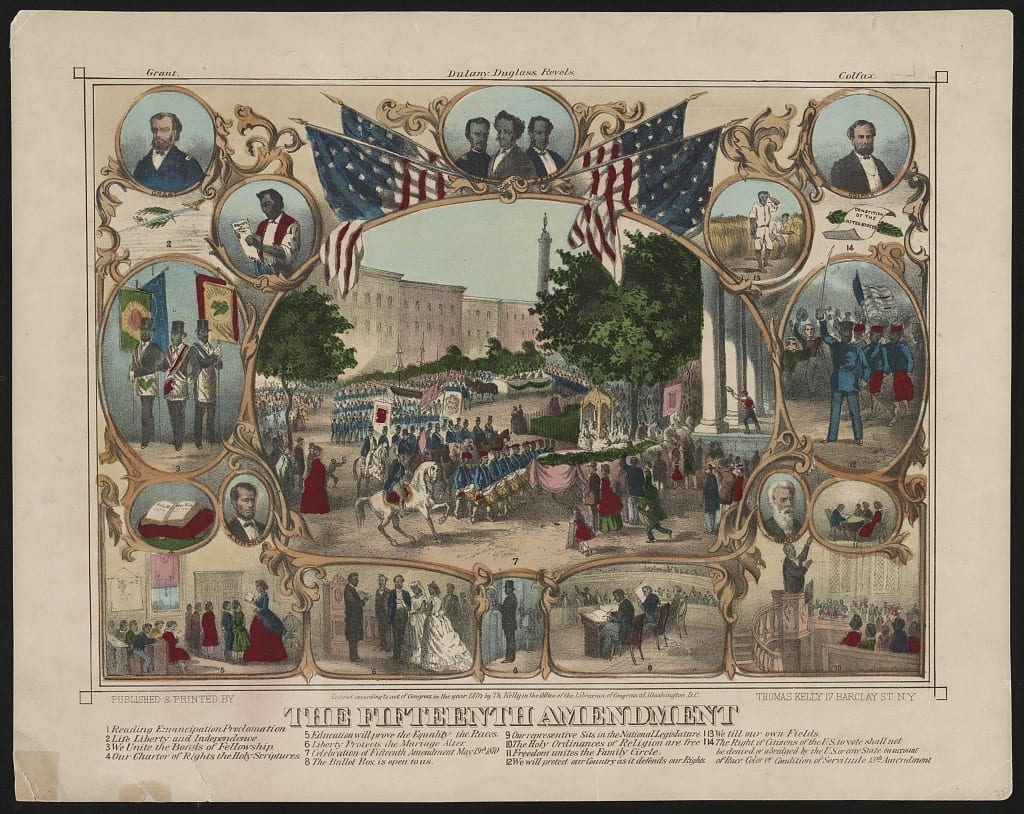

The sixth and fourteenth counts state the intent of the defendants to have been to hinder and prevent the citizens named, being of African descent, and colored, “in the free exercise and enjoyment of their several and respective rights and privileges to vote at any election to be thereafter by law had and held by the people in and of the said State of Louisiana” . . . . [W]e hold that the fifteenth amendment has invested the citizens of the United States with a new constitutional right, which is, exemption from discrimination in the exercise of the elective franchise on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. From this it appears that the right of suffrage is not a necessary attribute of national citizenship; but that exemption from discrimination in the exercise of that right on account of race, &c., is. The right to vote in the States comes from the States; but the right of exemption from the prohibited discrimination comes from the United States. The first has not been granted or secured by the Constitution of the United States; but the last has been.

Inasmuch, therefore, as it does not appear in these counts that the intent of the defendants was to prevent these parties from exercising their right to vote on account of their race, &c., it does not appear that it was their intent to interfere with any right granted or secured by the Constitution or laws of the United States. We may suspect that race was the cause of the hostility; but it is not so averred. . . .

We are, therefore, of the opinion that the [indictments] do not contain charges of a criminal nature made indictable under the laws of the United States. . . They do not show that it was the intent of the defendants, by their conspiracy, to hinder or prevent the enjoyment of any right granted or secured by the Constitution. . . .

The order of the Circuit Court arresting the judgment upon the verdict is. . . affirmed; and the cause remanded, with instructions to discharge the defendants.

Totten, Administrator, v. United States

April 10, 1876

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.