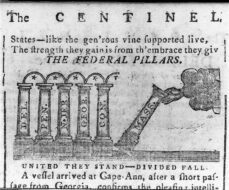

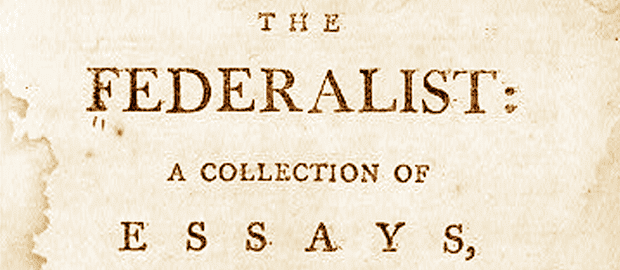

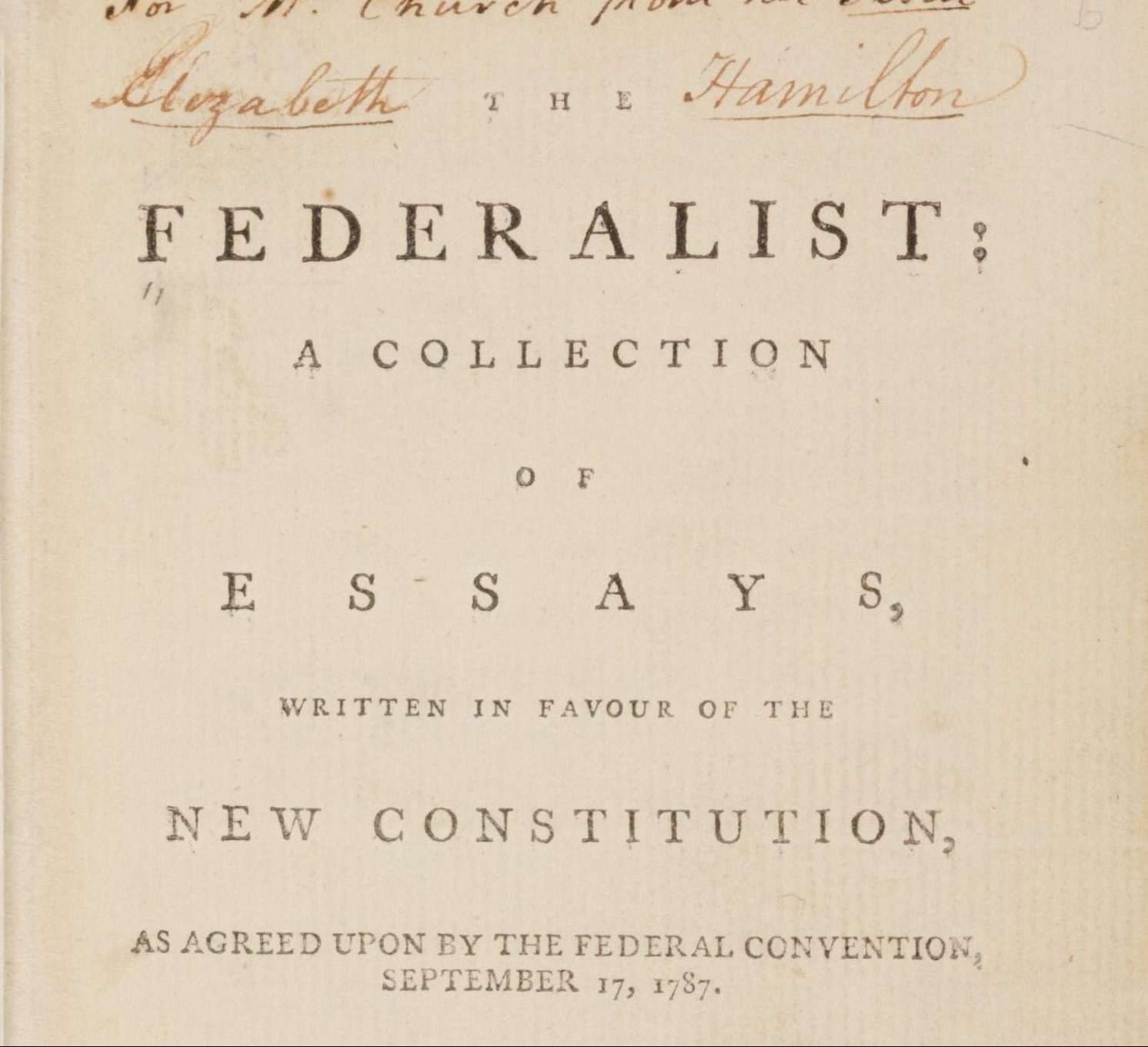

Introduction

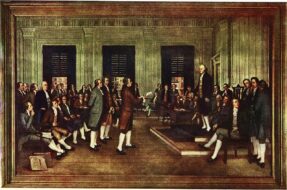

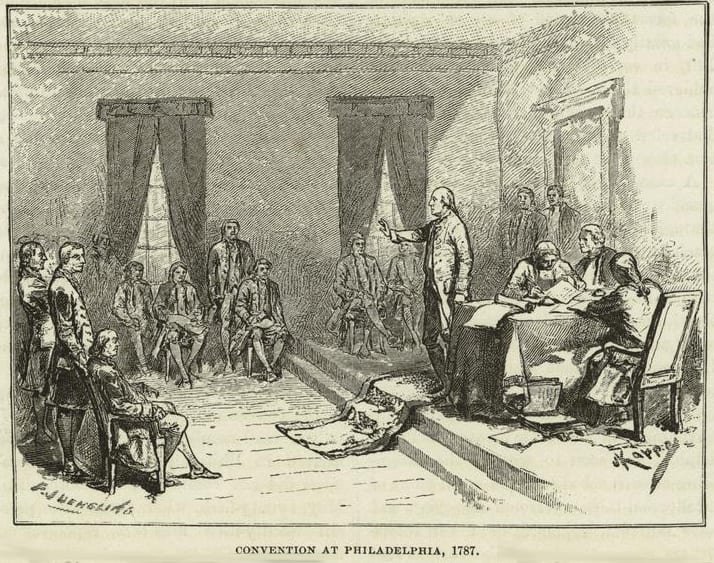

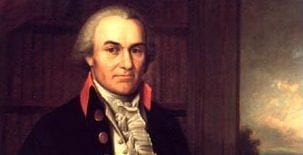

The Virginia Plan, introduced by Edmund Randolph on May 29, called for the creation of a National Executive elected by the Congress. In June, the delegates had agreed on a single executive who would serve a seven-year term and be ineligible for reelection. Some delegates wanted to settle the issue of re-eligibility first. Others wanted to fix the length of term before proceeding further. Still others wanted to discuss how the executive would be elected before considering anything else. Finally, another group of delegates thought that the powers of the president should be the primary question to be settled.

The biggest issue was how to elect the president. On June 9, the delegates defeated a motion to have the president elected by state executives. On June 18, Hamilton surprised the delegates with a proposal for a president for life. The delegates revisited the four main issues on several days in July. On July 17, the delegates agreed again to a single executive elected by the National legislature, and to be re-elected rather than serve during good behavior. On July 18 and 19, the delegates revisited the issue of whether the president should be eligible for reelection and considered the idea that the president should be elected by electors chosen by state legislatures. On July 20, a proposal permitting the impeachment of the president was approved. On July 24, the delegates returned to the earlier position: the president should be elected by the national legislature. Finally, on July 26, the delegates approved a seven-year term for the president. But he would be ineligible for reelection.

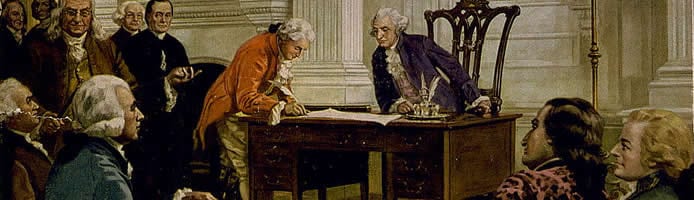

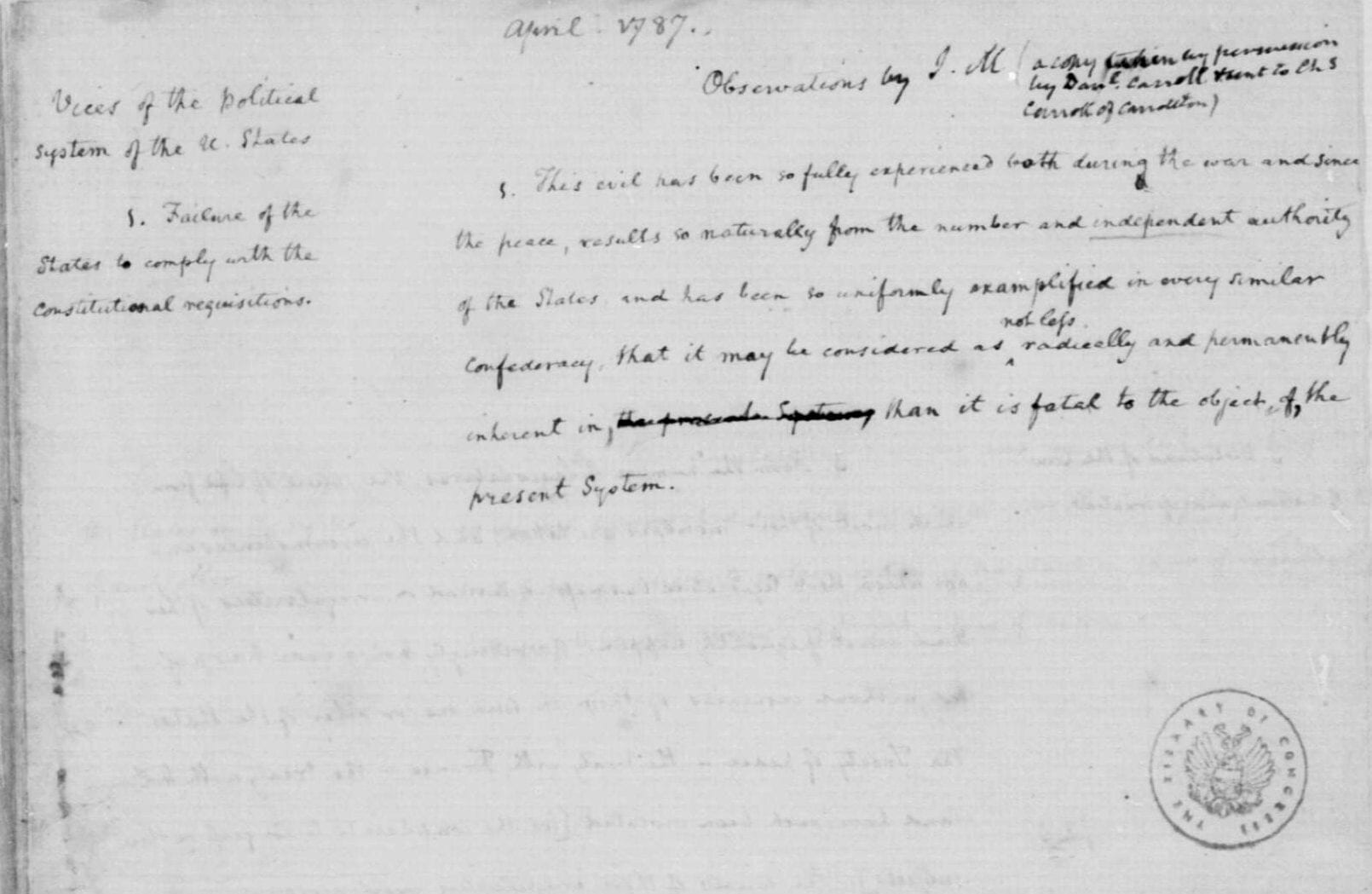

On August 24, the delegates turned to the presidential article of the Committee of Detail Report and rejected four different modes of electing the president. In the end, the Convention selected members of the Brearly Committee whose main objective was to settle the presidential election clause. The Brearly Committee, comprising Gilman, King, Sherman, Brearly, Gouverneur Morris, Dickinson, Carroll, Madison, Williamson, Butler, and Baldwin, proposed the adoption of an Electoral College in which both the people and the states were represented in the election of the president. The president was to be elected for four years and be eligible for reelection. This document presents the delegates’ discussion of the Brearly Committee report.

Source: Gordon Lloyd, ed., Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 by James Madison, a Member (Ashland, OH: Ashbrook Center, 2014) 473–79, 485–99.

September 4

In Convention, – Mr. BREARLY,[1] from the Committee of 11, made a further partial report as follows:

“The Committee of 11, to whom sundry resolutions, etc., were referred on the thirty-first of August, report, that in their opinion the following additions and alterations should be made to the Report before the Convention, viz.[2]:

“1. The first clause of Article 7, Section 1,[3] to read as follows: ‘The Legislature shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.’

“2. At the end of the second clause of Article 7, Section 1, add, ‘and with the Indian tribes.’

“3. In the place of the 9th Article, Section 1, to be inserted: ‘The Senate of the United States shall have power to try all impeachments; but no person shall be convicted without the concurrence of two-thirds of the members present.’

“4. After the word ‘Excellency,’ in Section 1, Article 10, to be inserted: ‘He shall hold his office during the term of four years, and together with the Vice President chosen for the same term, be elected in the following manner, viz.: Each State shall appoint, in such manner as its Legislature may direct, a number of Electors equal to the whole number of Senators and members of the House of Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Legislature. The Electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by ballot for two persons, of whom one at least shall not be an inhabitant of the same State with themselves; and they shall make a list of all the persons voted for, and of the number of votes for each, which list they shall sign and certify, and transmit, sealed, to the seat of the General Government, directed to the President of the Senate. The President of the Senate shall, in that House, open all the certificates, and the votes shall be then and there counted. The person having the greatest number of votes shall be the President, if such number be a majority of that of the Electors; and if there be more than one who have such a majority, and have an equal number of votes, then the Senate shall immediately choose by ballot one of them for President; but if no person have a majority, then from the five highest on the list the Senate shall choose by ballot the President; and in every case after the choice of the President, the person having the greatest number of votes shall be Vice President. But if there should remain two or more who have equal votes, the Senate shall choose from them the Vice President. The Legislature may determine the time of choosing and assembling the Electors, and the manner of certifying and transmitting their votes.’

“5. Section 2. ‘No person except a natural born citizen, or a citizen of the United States at the time of the adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the office of President; nor shall any person be elected to that office who shall be under the age of thirty-five years, and who has not been, in the whole, at least fourteen years a resident within the United States.’

“6. Section 3. ‘The Vice President shall be ex officio President of the Senate; except when they sit to try the impeachment of the President; in which case the Chief Justice shall preside, and excepting also when he shall exercise the powers and duties of President; in which case, and in case of his absence, the Senate shall choose a president pro tempore. The Vice President, when acting as President of the Senate, shall not have a vote unless the House be equally divided.’

“7. Section 4. ‘The President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall have power to make treaties; and he shall nominate, and, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall appoint ambassadors, and other public ministers, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other officers of the United States, whose appointments are not otherwise herein provided for. But no treaty shall be made without the consent of two-thirds of the members present.’

“8. After the words, ‘into the service of the United States,’ in Section 2, Article 10, add ‘and may require the opinion in writing of the principal officer in each of the Executive Departments, upon any subject relating to the duties of their respective offices.’

“9. The latter part of Section 2, Article 10, to read as follows: ‘He shall be removed from his office on impeachment by the House of Representatives, and conviction by the Senate, for treason or bribery; and in case of his removal as aforesaid, death, absence, resignation, or inability to discharge the powers or duties of his office, the Vice President shall exercise those powers and duties until another President be chosen, or until the inability of the President be removed.’”

The first clause of the Report was agreed to, nem. con.[4]

The second clause was also agreed to, nem. con.

The third clause was postponed, in order to decide previously on the mode of electing the President.

The fourth clause was accordingly taken up.

Mr. GORHAM[5] disapproved of making the next highest after the President the Vice President, without referring the decision to the Senate in case the next highest should have less than a majority of votes. As the regulation stands, a very obscure man with very few votes may arrive at that appointment.

Mr. SHERMAN[6] said the object of this clause of the Report of the Committee was to get rid of the ineligibility which was attached to the mode of election by the Legislature, and to render the Executive independent of the Legislature. As the choice of the President was to be made out of the five highest, obscure characters were sufficiently guarded against in that case; and he had no objection to requiring the Vice President to be chosen in like manner, where the choice was not decided by a majority in the first instance.

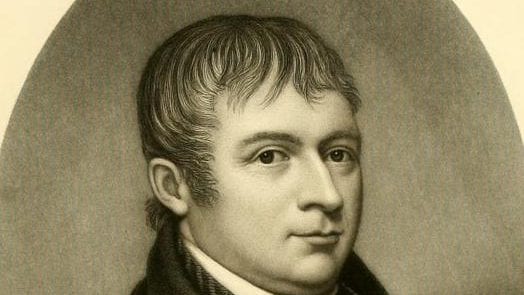

Mr. MADISON[7] was apprehensive that by requiring both the President and Vice President to be chosen out of the five highest candidates, the attention of the electors would be turned too much to making candidates, instead of giving their votes in order to a definitive choice. Should this turn be given to the business, the election would in fact be consigned to the Senate altogether. It would have the effect, at the same time, he observed, of giving the nomination of the candidates to the largest States.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS[8] concurred in, and enforced, the remarks of Mr. MADISON.

Mr. RANDOLPH[9] and Mr. PINCKNEY[10] wished for a particular explanation, and discussion, of the reasons for changing the mode of electing the Executive.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS said, he would give the reasons of the Committee, and his own. The first was the danger of intrigue and faction, if the appointment should be made by the Legislature. The next was the inconvenience of an ineligibility required by that mode, in order to lessen its evils. The third was the difficulty of establishing a court of impeachments, other than the Senate, which would not be so proper for the trial, nor the other branch, for the impeachment of the President, if appointed by the Legislature. In the fourth place, nobody had appeared to be satisfied with an appointment by the Legislature. In the fifth place, many were anxious even for an immediate choice by the people. And finally, the sixth reason was the indispensable necessity of making the Executive independent of the Legislature. As the electors would vote at the same time, throughout the United States, and at so great a distance from each other, the great evil of cabal was avoided. It would be impossible, also, to corrupt them. A conclusive reason for making the Senate, instead of the Supreme Court, the judge of impeachments, was, that the latter was to try the President, after the trial of the impeachment.

Colonel MASON[11] confessed that the plan of the Committee had removed some capital objections, particularly the danger of cabal and corruption. It was liable, however, to this strong objection, that nineteen times in twenty the President would be chosen by the Senate, an improper body for the purpose.

Mr. BUTLER[12] thought the mode not free from objections; but much more so than an election by the legislature, where, as in elective monarchies, cabal, faction, and violence would be sure to prevail.

Mr. PINCKNEY stated as objections to the mode, – first, that it threw the whole appointment in fact, into the hands of the Senate. Secondly, the electors will be strangers to the several candidates, and of course unable to decide on their comparative merits. Thirdly, it makes the Executive re-eligible, which will endanger the public liberty. Fourthly, it makes the same body of men which will, in fact, elect the President, his judges in case of an impeachment.

Mr. WILLIAMSON[13] had great doubts whether the advantage of re-eligibility would balance the objection to such a dependence of the President on the Senate for his reappointment. He thought, at least, the Senate ought to be restrained to the two highest on the list.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS said, the principal advantage aimed at was, that of taking away the opportunity for cabal. The President may be made, if thought necessary, ineligible, on this as well as on any other mode of election. Other inconveniences may be no less redressed on this plan than any other.

Mr. BALDWIN[14] thought the plan not so objectionable, when well considered, as at first view. The increasing intercourse among the people of the States would render important characters less and less unknown; and the Senate would consequently be less and less likely to have the eventual appointment thrown into their hands.

Mr. WILSON.[15] This subject has greatly divided the House, and will also divide the people out of doors.[16] It is in truth the most difficult of all on which we have had to decide. He had never made up an opinion on it entirely to his own satisfaction. He thought the plan, on the whole, a valuable improvement on the former. It gets rid of one great evil, that of cabal and corruption; and Continental characters will multiply as we more and more coalesce, so as to enable the Electors in every part of the Union to know and judge of them. It clears the way also for a discussion of the question of re-eligibility, on its own merits, which the former mode of election seemed to forbid. He thought it might be better, however, to refer the eventual appointment to the Legislature than to the Senate, and to confine it to a smaller number than five of the candidates. The eventual election by the Legislature would not open cabal anew, as it would be restrained to certain designated objects of choice; and as these must have had the previous sanction of a number of the States; and if the election be made as it ought, as soon as the votes of the Electors are opened, and it is known that no one has a majority of the whole, there can be little danger of corruption. Another reason for preferring the Legislature to the Senate in this business was, that the House of Representatives will be so often changed as to be free from the influence, and faction, to which the permanence of the Senate may subject that branch.

Mr. RANDOLPH preferred the former mode of constituting the Executive; but if the change was to be made, he wished to know why the eventual election was referred to the Senate, and not to the Legislature? He saw no necessity for this, and many objections to it. He was apprehensive, also, that the advantage of the eventual appointment would fall into the hands of the States near the seat of government.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS said the Senate was preferred because fewer could then say to the President, “You owe your appointment to us.” He thought the President would not depend so much on the Senate for his reappointment, as on his general good conduct.

The further consideration of the Report was postponed, that each member might take a copy of the remainder of it. . . .

September 6

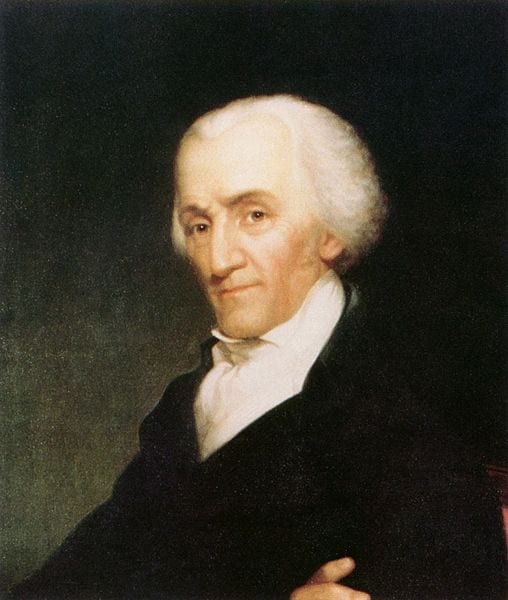

In Convention, – Mr. KING[17] and Mr. GERRY[18] moved to insert in the fourth clause of the Report, after the words, “may be entitled in the Legislature,” the words following: “But no person shall be appointed an Elector who is a member of the Legislature of the United States, or who holds any office of profit or trust under the United States”; which passed, nem. con.

Mr. GERRY proposed, as the President was to be elected by the Senate out of the five highest candidates, that if he should not at the end of his term be re-elected by a majority of the Electors, and no other candidate should have a majority, the eventual election should be made by the Legislature. This, he said, would relieve the President from his particular dependence on the Senate for his continuance in office.

Mr. KING liked the idea, as calculated to satisfy particular members, and promote unanimity; and as likely to operate but seldom.

Mr. READ[19] opposed it; remarking, that if individual members were to be indulged, alterations would be necessary to satisfy most of them.

Mr. WILLIAMSON espoused it, as a reasonable precaution against the undue influence of the Senate.

Mr. SHERMAN liked the arrangement as it stood, though he should not be averse to some amendments. He thought, he said, that if the Legislature were to have the eventual appointment, instead of the Senate, it ought to vote in the case by States, – in favor of the small States, as the large states would have so great an advantage in nominating the candidates.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS thought favorably of Mr. GERRY’S proposition. It would free the President from being tempted, in naming to offices, to conform to the will of the Senate, and thereby virtually give the appointments to office to the Senate.

Mr. WILSON said, that he had weighed carefully the Report of the Committee for remodeling the constitution of the Executive; and on combining it with other parts of the plan, he was obliged to consider the whole as having a dangerous tendency to aristocracy; as throwing a dangerous power into the hands of the Senate. They will have, in fact, the appointment of the President, and, through his dependence on them, the virtual appointment to offices; among others, the officers of the Judiciary department. They are to make treaties; and they are to try all impeachments. In allowing them thus to make the Executive and Judiciary appointments, to be the court of impeachments, and to make treaties which are to be laws of the land, the Legislative, Executive, and Judiciary powers are all blended in one branch of the Government. The power of making treaties involves the case of subsidies, and here, as an additional evil, foreign influence is to be dreaded. According to the plan as it now stands, the President will not be the man of the people, as he ought to be; but the minion of the Senate. He cannot even appoint a tide-waiter[20] without the Senate. He had always thought the Senate too numerous a body for making appointments to office. The Senate will, moreover, in all probability, be in constant session. They will have high salaries. And with all these powers, and the President in their interest, they will depress the other branch of the Legislature, and aggrandize themselves in proportion. Add to all this, that the Senate, sitting in conclave, can by holding up to their respective States various and improbable candidates, contrive so to scatter their votes, as to bring the appointment of the President ultimately before themselves. Upon the whole, he thought the new mode of appointing the President, with some amendments, a valuable improvement; but he could never agree to purchase it at the price of the ensuing parts of the Report, nor befriend a system of which they make a part.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS expressed his wonder at the observations of Mr. WILSON, so far as they preferred the plan in the printed Report to the new modification of it before the House; and entered into a comparative view of the two, with an eye to the nature of Mr. WILSON’S objections to the last. By the first, the Senate, he observed, had a voice in appointing the President out of all the citizens of the United States; by this they were limited to five candidates, previously nominated to them, with a probability of being barred altogether by the successful ballot of the Electors. Here, surely was no increase of power. They are now to appoint Judges, nominated to them by the President. Before, they had the appointment without any agency whatever of the President. Here again was surely no additional power. If they are to make treaties, as the plan now stands, the power was the same in the printed plan. If they are to try impeachments, the Judges must have been triable by them before. Wherein, then, lay the dangerous tendency of the innovations to establish an aristocracy in the Senate? As to the appointment of officers, the weight of sentiment in the House was opposed to the exercise of it by the President alone; though it was not the case with himself. If the Senate would act as was suspected, in misleading the States into a fallacious disposition of their votes for a President, they would, if the appointment were withdrawn wholly from them, make such representations in their several States where they have influence, as would favor the object of their partiality.

Mr. WILLIAMSON, replying to Mr. MORRIS, observed, that the aristocratic complexion proceeds from the change in the mode of appointing the President, which makes him dependent on the Senate.

Mr. CLYMER[21] said, that the aristocratic part, to which he could never accede, was that, in the printed plan, which gave the Senate the power of appointing to offices.

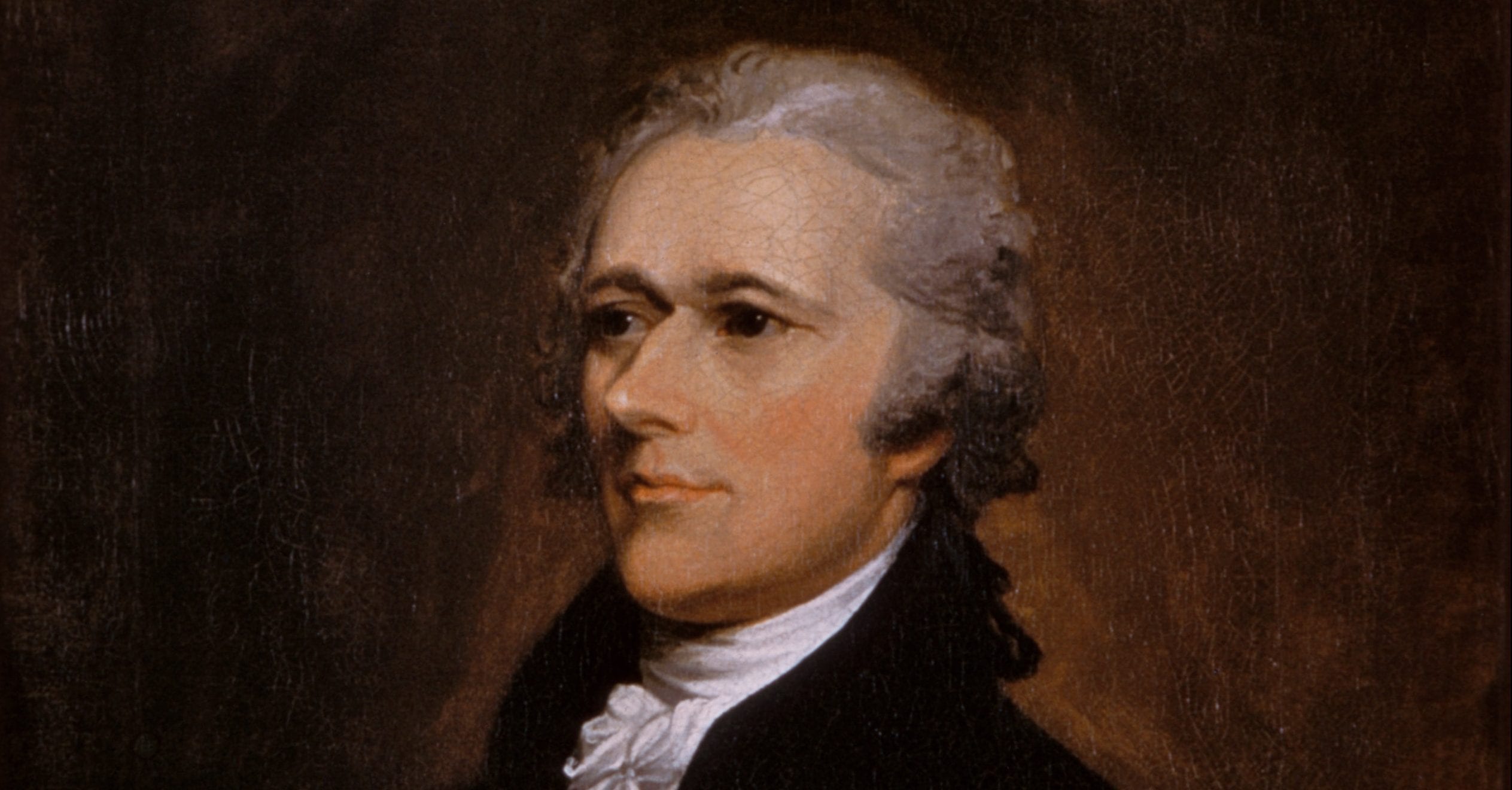

Mr. HAMILTON[22] said, that he had been restrained from entering into the discussions, by his dislike of the scheme of government in general; but as he meant to support the plan to be recommended, as better than nothing, he wished in this place to offer a few remarks. He liked the new modification, on the whole, better than that in the printed Report. In this, the President was a monster, elected for seven years, and ineligible afterwards; having great powers in appointments to office; and continually tempted, by this constitutional disqualification, to abuse them in order to subvert the Government. Although he should be made re-eligible, still, if appointed by the Legislature, he would be tempted to make use of corrupt influence to be continued in office. It seemed peculiarly desirable, therefore, that some other mode of election should be devised. Considering the different views of different States, and the different districts, Northern, Middle, and Southern, he concurred with those who thought that the votes would not be concentered, and that the appointment would consequently, in the present mode, devolve on the Senate. The nomination to offices will give great weight to the President. Here, then, is a mutual connection and influence, that will perpetuate the President, and aggrandize both him and the Senate. What is to be the remedy? He saw none better than to let the highest number of ballots, whether a majority or not, appoint the President. What was the objection to this? Merely that too small a number might appoint. But as the plan stands, the Senate may take the candidate having the smallest number of votes, and make him President.

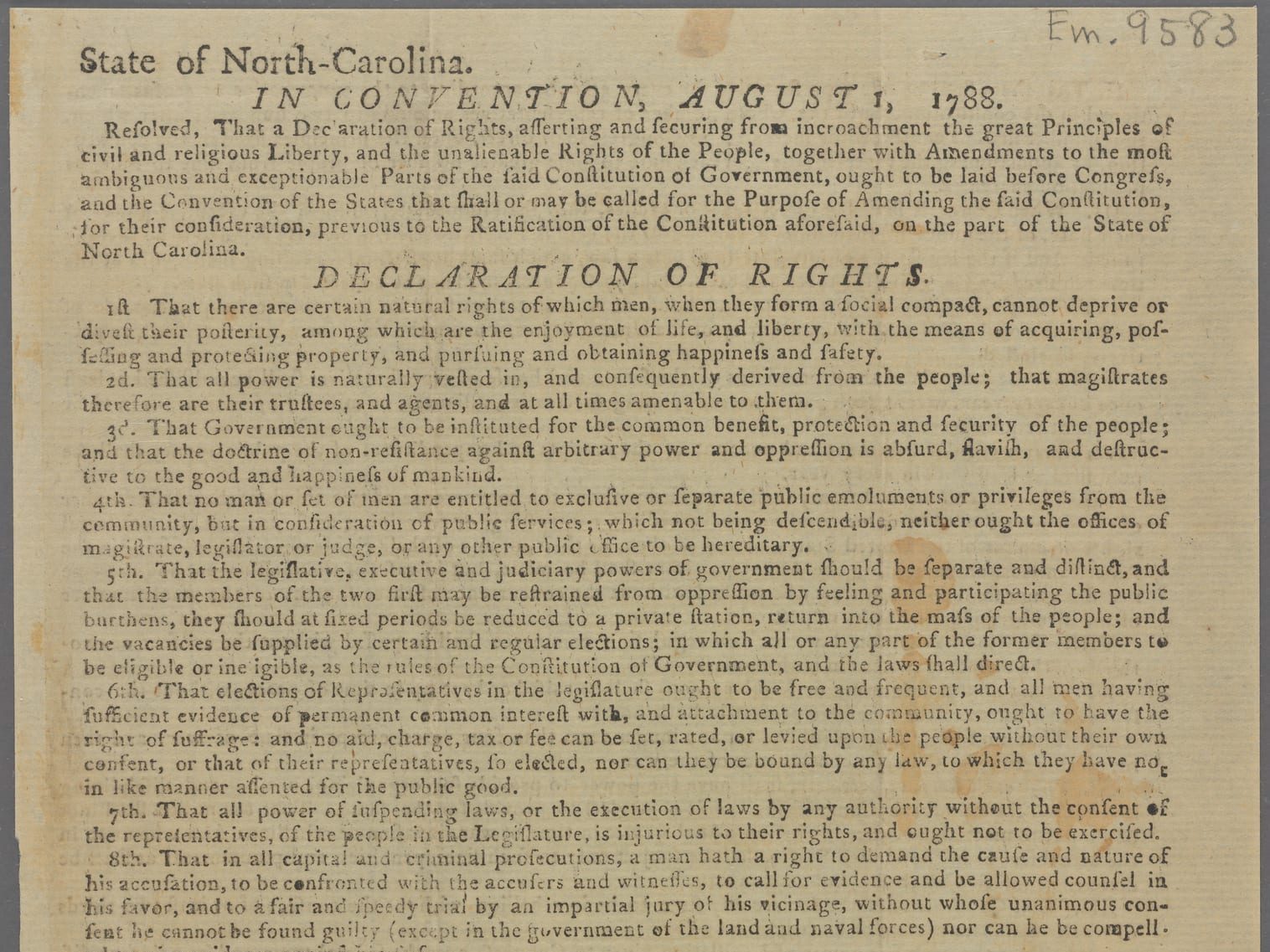

Mr. SPAIGHT[23] and Mr. WILLIAMSON moved to insert “seven,” instead of “four” years, for the term of the President.

On this motion, – New Hampshire, Virginia, North Carolina, aye, – 3; Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, South Carolina, Georgia, no, – 8.

Mr. SPAIGHT and Mr. WILLIAMSON then moved to insert “six;” instead of “four.”

On which motion, – North Carolina, South Carolina, aye, – 2; New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Georgia, no, – 9.

On the term “four” all the States were aye, except North Carolina, no.

On the question on the fourth clause in the Report, for appointing the President by Electors, down to the words, “entitled in the Legislature,” inclusive, – New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Georgia, aye, – 9; North Carolina, South Carolina, no, – 2.

It was moved, that the Electors meet at the seat of the General Government; which passed in the negative, – North Carolina only being, aye.

It was then moved to insert the words, “under the seal of the State,” after the word “transmit,” in the fourth clause of the Report; which was disagreed to; as was another motion to insert the words, “and who shall have given their votes,” after the word “appointed,” in the fourth clause of the Report, as added yesterday on motion of Mr. DICKINSON.[24]

On several motions, the words, “in presence of the Senate and House of Representatives,” were inserted after the word “counted”; and the word “immediately,” before the word “choose”; and the words, “of the electors,” after the word “votes.”

Mr. SPAIGHT said, if the election by Electors is to be crammed down, he would prefer their meeting altogether, and deciding finally without any reference to the Senate; and moved, “that the Electors meet at the seat of the General Government.”

Mr. WILLIAMSON seconded the motion; on which all the States were in the negative, except North Carolina.

On motion, the words, “But the election shall be on the same day throughout the United States,” were added after the words, “transmitting their votes.”

New Hampshire, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye, – 8; Massachusetts, New Jersey, Delaware, no, – 3.

On the question on the sentence in the fourth clause, “if such number be a majority of that of the Electors appointed,” – New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, South Carolina, Georgia, aye, – 8; Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, no, – 3.

On a question on the clause referring the eventual appointment of the President to the Senate, – New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, ay, – 7; North Carolina, no. Here the call ceased.

Mr. MADISON, made a motion requiring two-thirds at least of the Senate to be present at the choice of a President.

Mr. PINCKNEY seconded the motion.

Mr. GORHAM thought it a wrong principle to require more than a majority in any case. In the present, it might prevent for a long time any choice of a President.

On the question moved by Mr. MADISON and Mr. PINCKNEY, – New Hampshire, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye, – 6; Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, no, – 4; Massachusetts, absent.

Mr. WILLIAMSON suggested, as better than an eventual choice by the Senate, that this choice should be made by the Legislature, voting by States and not per capita.

Mr. SHERMAN suggested, “the House of Representatives,” as preferable to “the legislature”; and moved accordingly, to strike out the words, “The Senate shall immediately choose,” etc. and insert: “The House of Representatives shall immediately choose by ballot one of them for President, the members from each State having one vote.”

Colonel MASON liked the latter mode best, as lessening the aristocratic influence of the Senate.

On the motion of Mr. SHERMAN, – New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye, – 10; Delaware, no, – 1.

Mr. GOUVERNEUR MORRIS suggested the idea of providing that, in all cases, the President in office should not be one of the five candidates; but be only re-eligible in case a majority of the Electors should vote for him. (This was another expedient for rendering the President independent of the Legislative body for his continuance in office.)[25]

Mr. MADISON remarked, that as a majority of members would make a quorum in the House of Representatives, it would follow from the amendment of Mr. SHERMAN, giving the election to a majority of States, that the President might be elected by two States only, Virginia and Pennsylvania, which have eighteen members, if these States alone should be present.

On a motion, that the eventual election of President, in case of an equality of the votes of the Electors, be referred to the House of Representatives, – New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, aye, – 7; New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, no, – 3.

Mr. KING moved to add to the amendment of Mr. SHERMAN, “But a quorum for this purpose shall consist of a member or members from two-thirds of the States, and also of a majority of the whole number of the House of Representatives.”

Colonel MASON liked it, as obviating the remark of Mr. MADISON.

The motion, as far as “States,” inclusive, was agreed to. On the residue, to wit: “and also of a majority of the whole number of the House of Representatives,” it passed in the negative, – Massachusetts, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, aye, – 5; New Hampshire, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, South Carolina, Georgia, no, – 6.

The Report relating to the appointment of the Executive stands, as amended, as follows:

“He shall hold his office during the term of four years; and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same term, be elected in the following manner:

“Each State shall appoint, in such manner as its Legislature may direct, a number of electors equal to the whole number of Senators and members of the House of Representatives to which the state may be entitled in the Legislature.

“But no person shall be appointed an elector who is a member of the Legislature of the United States, or who holds any office of profit or trust under the United States.

“The electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by ballot for two persons, of whom one at least shall not be an inhabitant of the same State with themselves; and they shall make a list of all the persons voted for, and of the number of votes for each; which list they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the seat of the General Government, directed to the President of the Senate.

“The President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates, and the votes shall then be counted.

“The person having the greatest number of votes shall be the President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of electors appointed; and if there be more than one who have such majority, and have an equal number of votes, then the House of Representatives shall immediately choose by ballot one of them for President; the representation from each State having one vote. But if no person have a majority, then from the five highest on the list the House of Representatives shall, in like manner, choose by ballot the President. In the choice of a President by the House of Representatives, a quorum shall consist of a member or members from two-thirds of the States, (and the concurrence of a majority of all the States shall be necessary to such choice.)* And in every case after the choice of the President, the person having the greatest number of votes of the electors shall be the Vice President. But if there should remain two or more who have equal votes, the Senate shall choose from them the Vice President.

“The Legislature may determine the time of choosing the electors, and of their giving their votes; and the manner of certifying and transmitting their votes; but the election shall be on the same day throughout the United States.”

Adjourned.

* [Madison’s note]

This clause was not inserted on this day, but on the seventh of September.

- 1. David Brearly, New Jersey

- 2. abbreviation of the Latin videlicet (namely)

- 3. The draft of the Constitution, with articles and sections, delivered by the Committee of Detail on August 6 is the document that the Brearly Committee is discussing. The delegates argued over the contents of the Committee of Detail Report throughout the month of August and settled the powers of Congress, the shape of the Judiciary, and the future of the slave trade. The creation of the presidency had not yet been settled, however; the main stumbling block was how to elect the president.

- 4. an abbreviation of nemine contradicente, Latin for “no one dissenting”

- 5. Nathaniel Gorham, Massachusetts

- 6. Roger Sherman, Connecticut

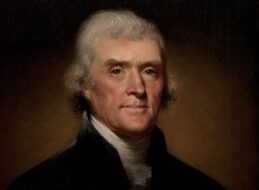

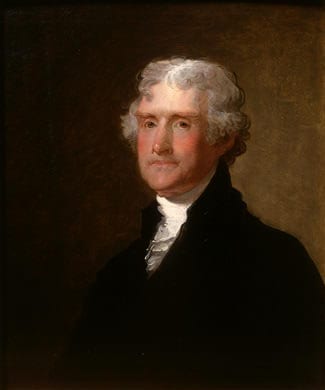

- 7. James Madison, Virginia

- 8. Gouverneur Morris, Pennsylvania

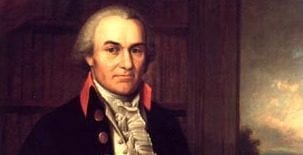

- 9. Edmund J. Randolph, Virginia

- 10. Charles Pinckney, South Carolina

- 11. George Mason, Virginia

- 12. Pierce Butler, South Carolina

- 13. Hugh Williamson, North Carolina

- 14. Abraham Baldwin, Georgia

- 15. James Wilson, Pennsylvania

- 16. that is, when the people consider what the Convention proposes as the new constitution

- 17. Rufus King, Massachusetts

- 18. Elbridge Gerry, Massachusetts

- 19. George Read, Delaware

- 20. a lower ranking customs officer who works at the docks

- 21. George Clymer, Pennsylvania

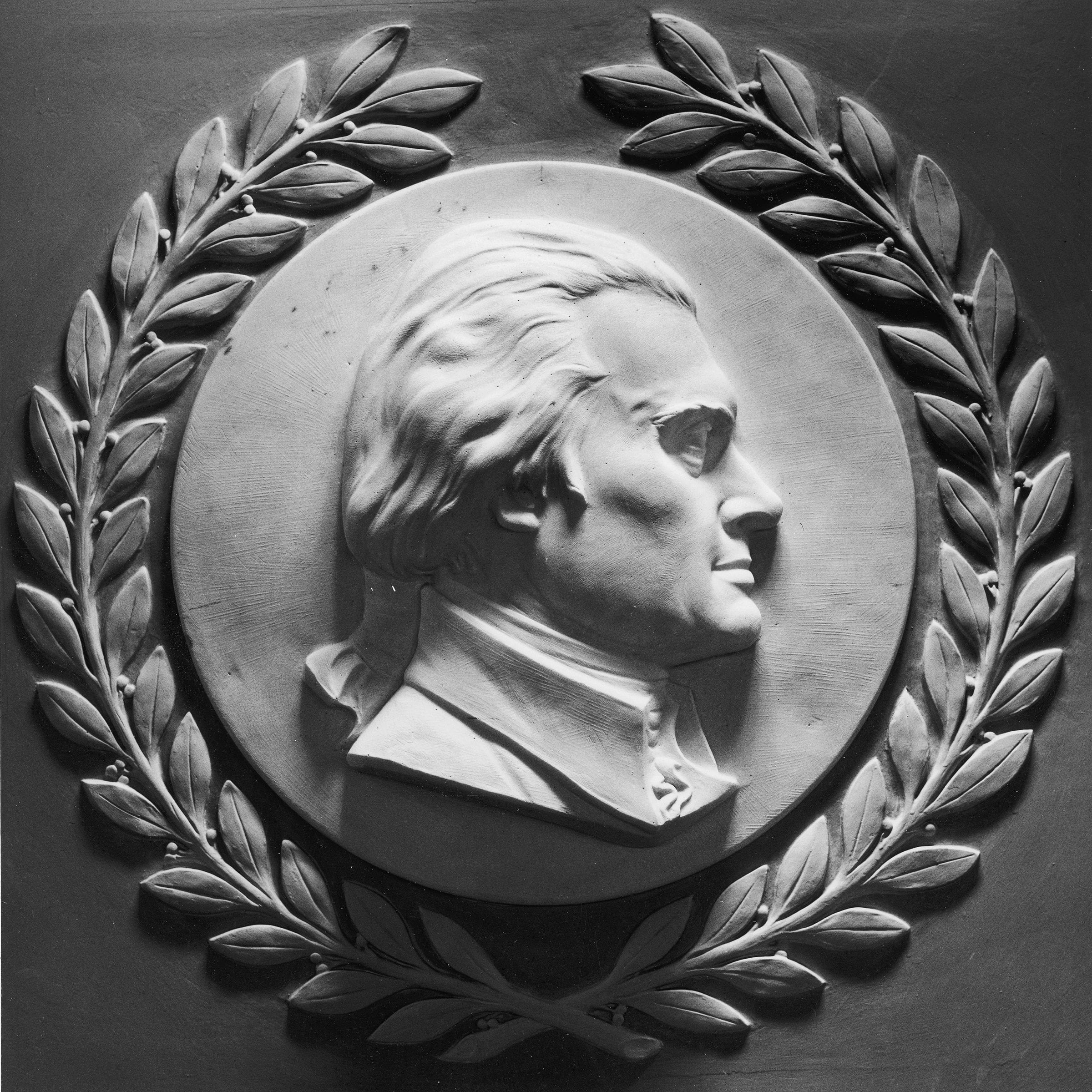

- 22. Alexander Hamilton, New York

- 23. Richard D. Spaight, North Carolina

- 24. John Dickinson, Delaware

- 25. The sentence inside the parentheses is Madison’s explanatory comment.

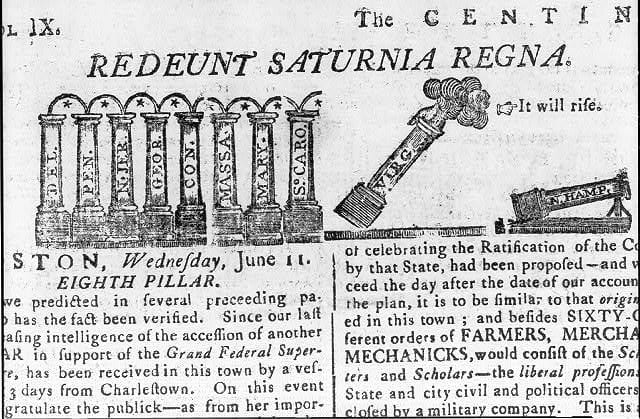

Foreign Spectator 15

September 04, 1787

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)